EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Thai sea freight services are expected to experience steady growth from 2025 to 2027, partly due to Thailand’s expansion into new export markets, the rise of e-commerce, government infrastructure development projects that integrate logistics networks, and the extension of transport links connecting Thailand to neighboring countries. On the supply side, operators are likely to increase their fleets to meet the anticipated rise in demand.

Nevertheless, the industry will face challenges that will come in the shape of: (i) widespread geopolitical tensions that will periodically add to transportation costs; (ii) intensifying competition as foreign operators form new alliances, potentially resulting in a loss of market share for Thai companies; (iii) growth in fleet sizes that may outpace expansion in demand; and (iv) stricter controls on pollution and the enforcement of the IMO 2023 regulations, which will add to business overheads. These headwinds will then tend to weigh on margins.

Krungsri Research view

Krungsri Research sees the market for sea freight services developing across different segments as described below.

-

Containerized shipping: shipping lines, and freight forwarders will see growing revenue, as growth in the global economy lifts consumption generally. However, the uptake of shipping services will strengthen only gradually. To ensure that ships sail at their maximum capacity, operators will have to balance sailings with demand carefully. In addition, competition will intensify within this segment, especially from foreign-owned operators, and the price wars that they might bring can cause Thai companies to lose their market shares.

-

Bulk carriers: Revenue will slowly recover. Demand for the goods most commonly shipped by these companies (commodities, construction materials, and metals and ores) is relatively stable, so operators can consistently book revenues from freights, charter fees, and surcharges. However, the earlier rise in new ship orders will mean that fleet sizes will expand, restraining the revenues’ growth.

-

Tankers: Turnover will improve as the economy strengthens and demand rallies against worries over potential shortages and as a hedge against price volatility, especially fuels. As their business revolves around products that are central to industry, players should be able to generate consistent revenues from the charter fee of ships and the selling of allocation space.

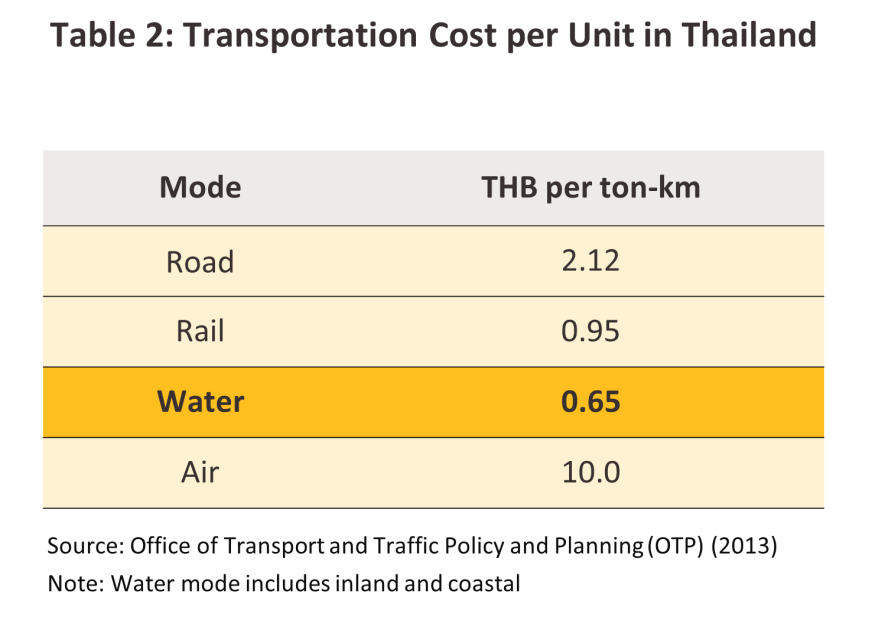

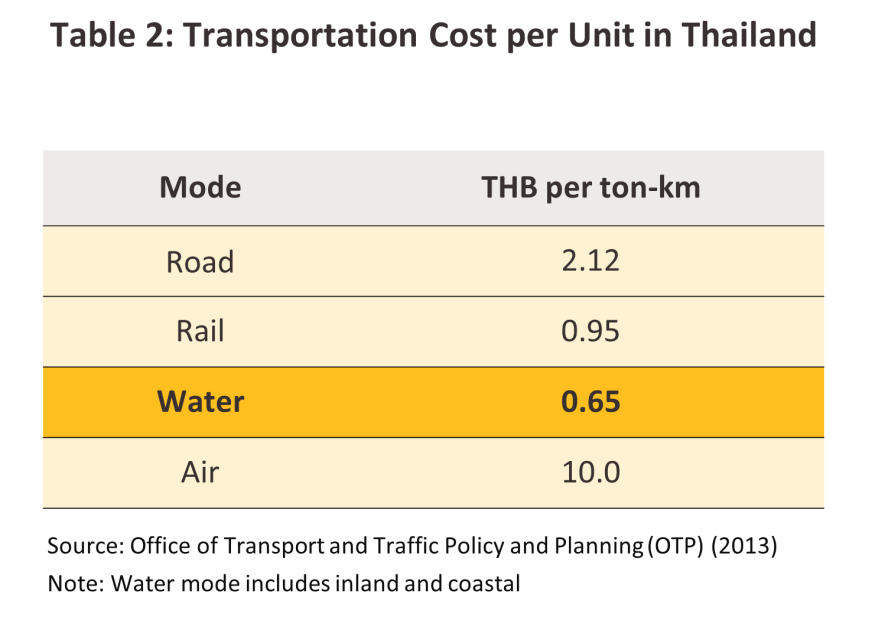

Overview

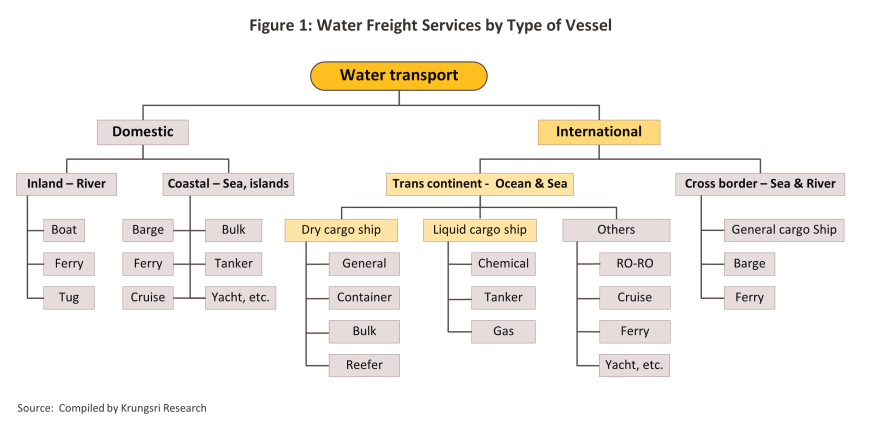

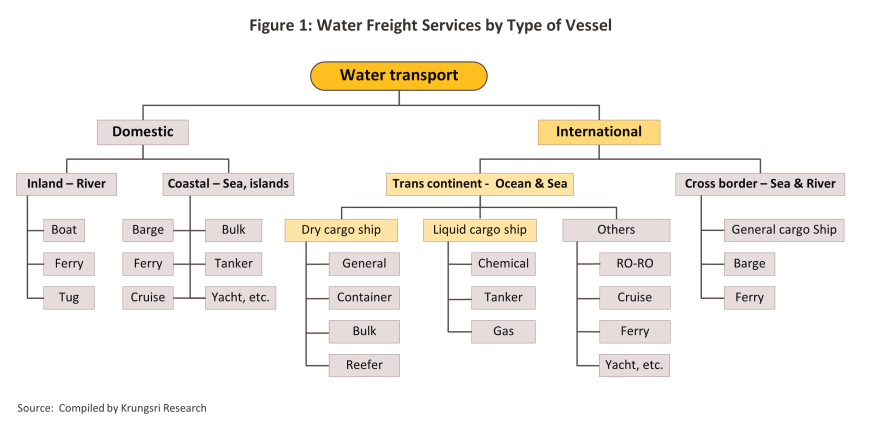

Sea freight plays a central role in facilitating international trade, and, in addition to underpinning the health of global supply chains by moving raw materials to production sites around the world, maritime trade is essential to ensuring that global markets continue to meet the needs of producers and consumers. The sea freight industry is linked to a broad range of other domestic and international activities, including warehousing, transportation, and end-point distribution. Therefore, there are a wide range of sea freight services provided by type of vessel (figure 1). Moving goods by maritime channels offers a number of advantages, most obviously that a large quantity of heavy, bulky goods may be shipped together, and this then makes sea freight considerably cheaper than alternatives for a given weight of goods (average freight charges come to THB 0.65/tonne/kilometer for sea transport, compared to THB 0.95, THB 2.12 and THB 10.0 for respectively rail-, road- and air-based alternatives)1/. In addition, maritime freight has the benefit of flexibility, have now generally been modernized with regard to both transportation systems and the fuels that they use, and containerization means that goods can be shipped with a high degree of safety. Nevertheless, it does have its disadvantages, that it is relatively slow in comparison to the alternatives, and it needs other transport modalities to transfer goods to final delivery points. The global merchant fleet currently transports over 80% of the world's trade by volume and 70% by value2/ (the latest data as of 2022).

Sea freight services3/ can be subdivided into several categories.

1) Services may be categorized according to the type of vessel or ocean carrier. These consist of (i) Ships moving dry cargo4/ including bulk carriers, container ships, and reefer containers (temperature-controlled containers) as well as specialist or multipurpose vessels (e.g., roll-on/roll-off or RO-RO ships), and (ii) Vessels moving liquid cargoes including oil tankers, LPG and LNG tankers, together with ships used to move chemicals, petrochemicals, other dangerous substances, vegetable oils, and so on.

2) Services may also be categorized according to the routes on which they operate. These consist of (i) Shippers run services on regular lines according to fixed schedules and for which freight rates are set for particular periods. Most of these services operate on the major trans-pacific, Asia-Europe and transatlantic routes, though intra-regional services also exist. (ii) Tramp or time charter services that run on lines and at times according to the terms of the hire agreement. Likewise, freight rates are also determined on an individual basis as set out in the charter agreement, though the hiring organization is often responsible for paying fuel costs.

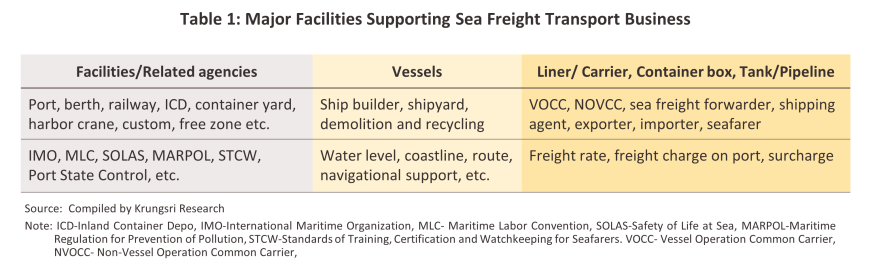

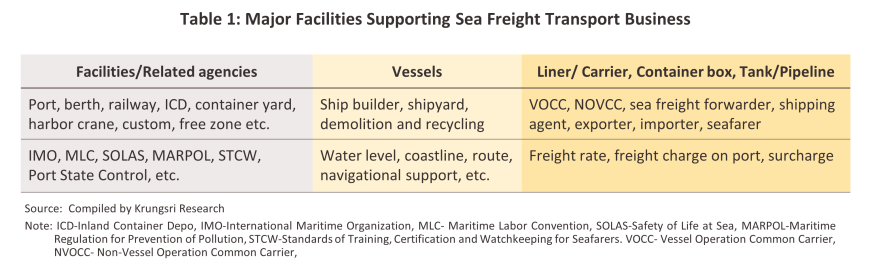

Sea freight companies operate globally to move goods port-to-port, though given the benefits that they offer with regard to both costs and time, operators generally rely on other companies or other parts of their commercial network for services including entering and exiting ports, dealing with customs, and offloading goods en route to a final destination (Table 1). The various types of sea freight operations are described below:

-

Shipping lines, vessel operating common carriers (VOCCs), and ocean common carriers operate their own fleets and either manage their own containers to shift goods on regular routes (most of these are thus large operations) or they may operate charter services (mostly undertaken by small, local operations). These typically run domestic and international branch offices or have partnered with other businesses to offer a similar service. Brokers will source shipping capacity or goods to ship, while agents will attempt to sell cargo space, thus ensuring that ship or freight utilization rates are as high as possible.

-

Shipping line agencies operate as middlemen selling cargo space to third parties. These include: (i) service operators and freight forwarders that do not have contracts with major carriers but that offer services to smaller clients moving lower volumes of goods; and (ii) non-vessel operating common carriers (NVOCCs) and international freight forwarders that hold contracts with shipping lines. These entities purchase cargo space to resell to their customers, along with providing related services such as stevedoring, storage solutions, container packing5/, and customs clearance.

Entering the sea freight business requires substantial capital investment and often involves long repayment periods. Companies must either build their own fleet or lease vessels for transportation. Staff need specialized expertise, and to ensure efficient cargo management in destination countries, businesses must either establish local branches or partner with trusted local entities. Additionally, the industry operates under complex international maritime regulations, including those related to labor conditions, pollution control, and the security of assets. Moreover, Operators also face risks from economic fluctuations, fuel price volatility, changes in global trade policies, and varying regulations and incentives in different regions.

Competition may be somewhat intense since goods are transported through international water and these are open to shippers worldwide. Revenue comes from the freight rates that operators charge, though these can vary depending on demand for space, the supply of capacity at a particular point in time, and the type of service be offered. The latter includes shipping goods on regular routes, in which case fees will be charged according to the volume of goods and the distance to the destination, or charter services, in which case fees will be agreed on an individual basis, though this might be for chartering an empty vessel or for the delivery of a pre-agreed cargo. The principal costs faced by operators are: (i) voyage costs which are largely accounted for by bunker fuel and piloting and port charges; (ii) other operating overheads, which include manning costs (this covers salaries and payments to staff such as per diem allowances), repair and maintenance of ships, insurance fees, and fees, charges and other expenses levied on operators; and (iii) capital costs incurred in the lease or purchase of ships and the interest that is charged on this.

Effective management can help to increase operating efficiencies and through this, add to profits. (i) Spending too long queueing for port calls to load/unload goods may affect an operator’s ability to take on or offload goods at the next port. Sea freight companies thus work with brokers and agents or with trusted partners and branch networks that are familiar with local operators and that have solid local connections, which then helps to reduce wasted time and to minimize costs. (ii) To hedge against risk from fluctuating exchange rates and energy price operators will typically take out insurance or enter into forward contracts. (iii) Arranging protection and indemnity insurance that covers cargo, ships, machinery, crew, and third-party liabilities helps to cut losses in the event of unexpected or unusual events, such as damage or loss to cargo, piracy, or unfavorable climatic events.

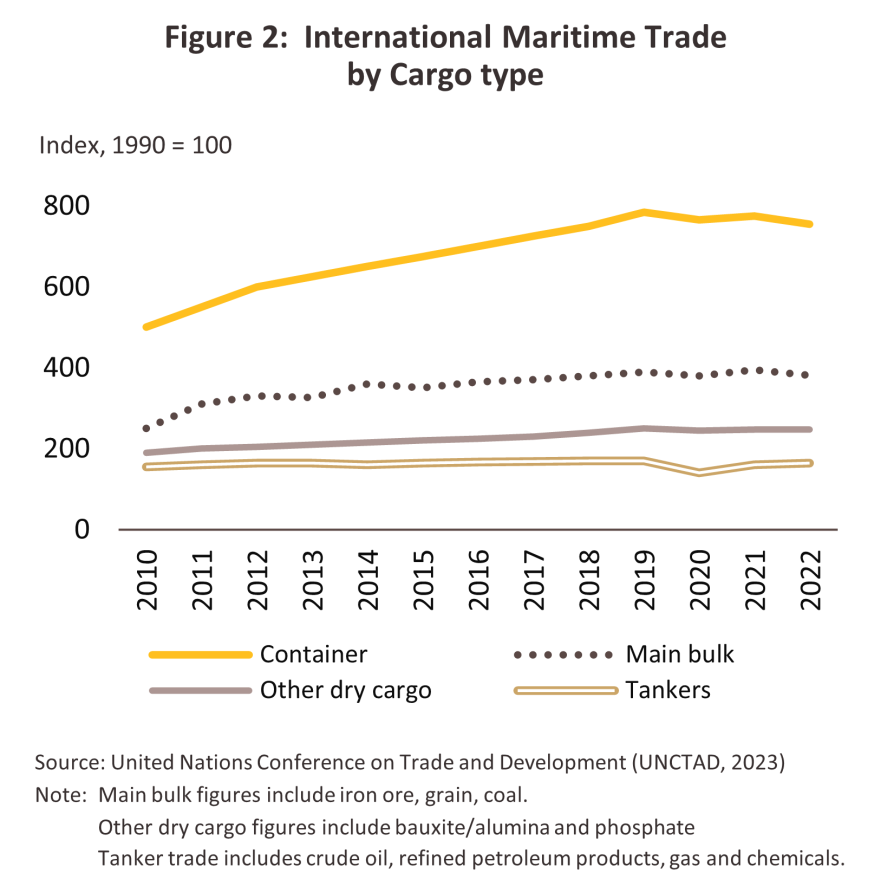

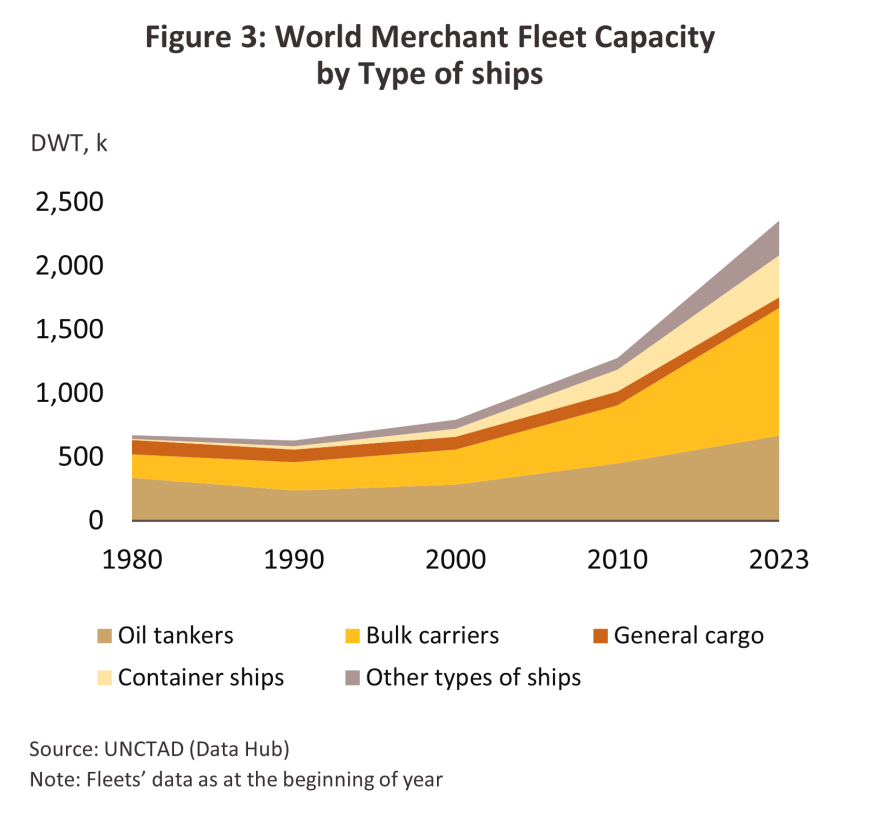

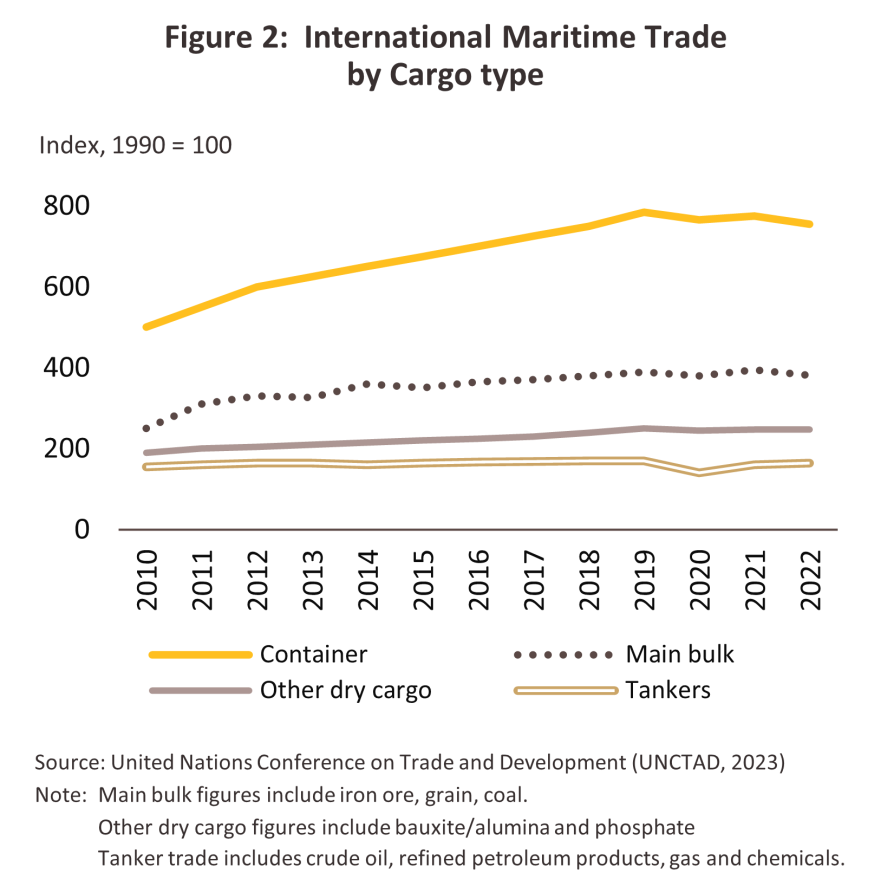

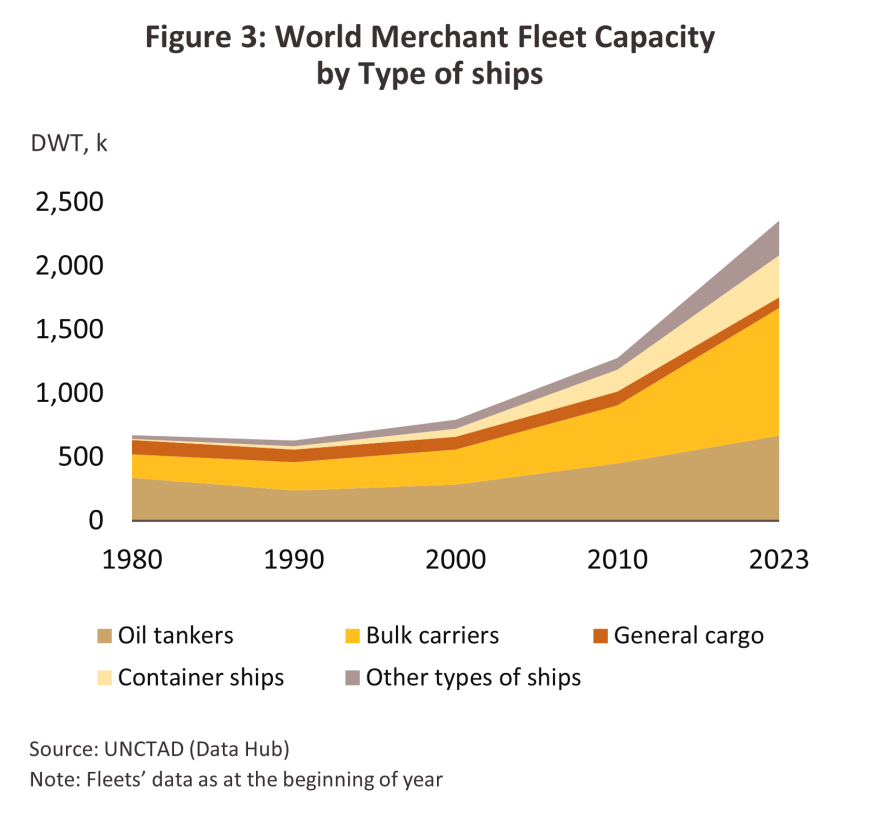

Demand for sea freight services has grown steadily, moving in step with expansion in global trade and the world economy. In the decade prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (2010-2019), the markets for containerized and bulk freight enjoyed average annual growth of respectively 5.8% and 5.0% (Figure 2 and Figure 3), and as a result, ships have been built larger to accommodate increasing quantities of cargo. For example, Chinese container ships can now carry over 24,000 TEUs (Twenty-Foot Equivalent Units), amounting to 240,000 tonnes of goods, while reducing carbon emissions by 6,000 tonnes annually. Over the same period, the global fleet's total carrying capacity increased by an average of 3.9% annually. However, the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020–2021 caused disruptions and delays in maritime operations. As of 2023, the average vessel age was 22.0 years, up from the average age of 20.6 years in the previous decade

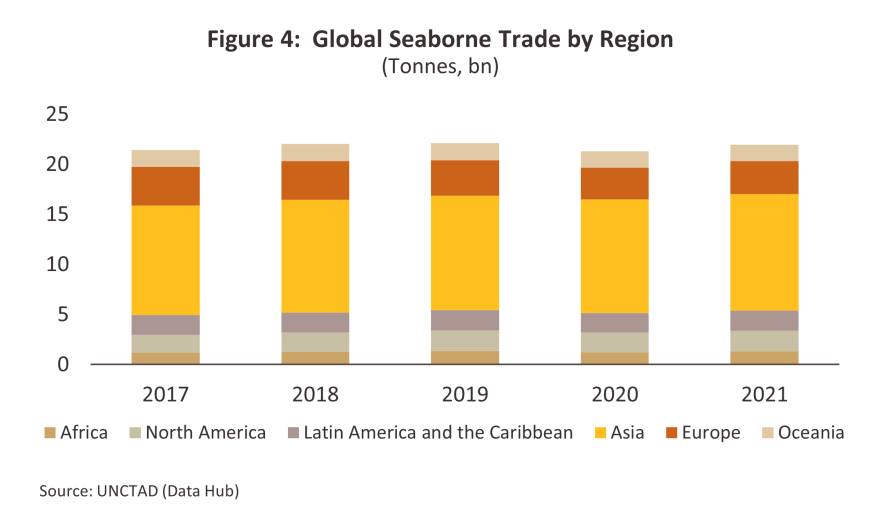

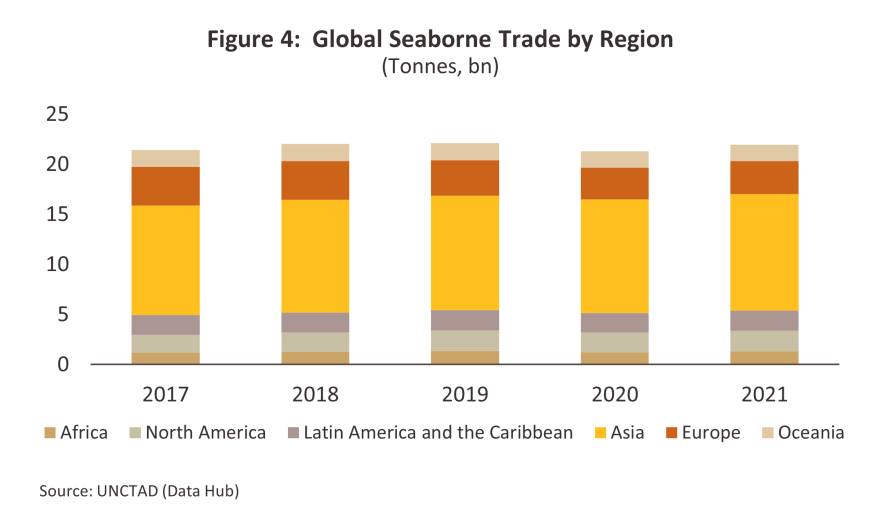

Asia is the world's leading region for sea freight, accounting for more than half of global maritime cargo volume (Figure 4) and utilizing 62.5% of all containers in circulation worldwide (source: UNCTAD). This dominance is driven by the region’s rapid economic growth and its role as a major hub for industrial and agricultural production, leading to significant demand for both imports and exports across the global market. Particularly, China, South Korea, and Singapore stand out as countries with highly developed and expansive maritime networks that span global routes. Within the ASEAN region’s sea freight, Singapore is the leading nation in terms of sea freight volume, reflecting its pivotal role in global trade. Singapore’s share of the global merchant fleet’s carrying capacity stood at 6.0%, making it the largest maritime player in ASEAN. Following Singapore are Indonesia and Vietnam, with shares of 1.4% and 0.6%, respectively.

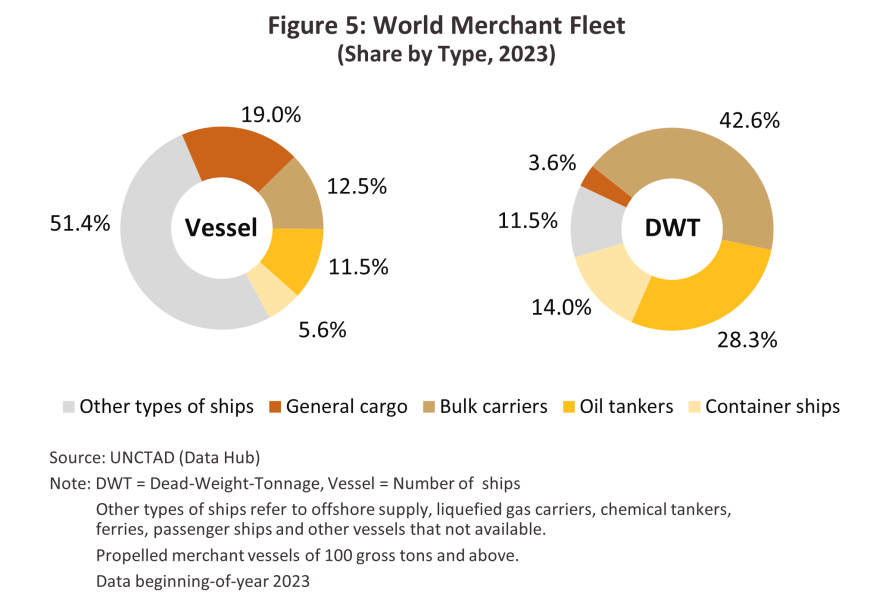

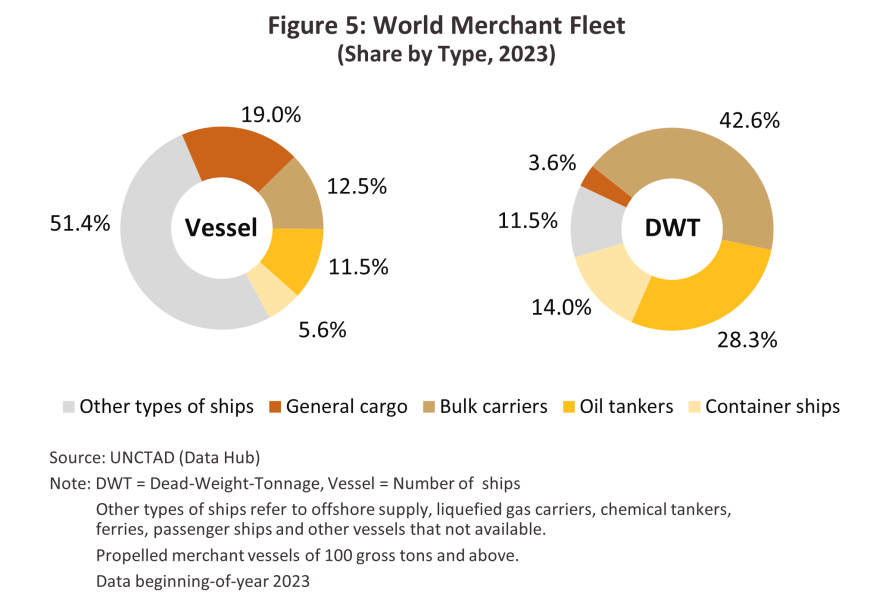

As of 2023, the global merchant fleet numbered 108,789 ships (Figure 5) with a combined tonnage of 2.3 billion dead-weight-tonnage (DWT). These vessels may be split into various classes. General carriers comprise 19.0% of the total, though by tonnage this falls to just 3.6%, and these have an average working life of somewhat longer than 27 years. By number, bulk carriers are in second place with 12.5% of the total, while by weight, they account for a full 42.6% of the global fleet. These have an average lifespan of 12 years. 11.5% of the fleet are oil tankers (28.3% of the total by tonnage), and these have a lifespan of 20 years, container ships comprise 5.6% of the total by number but 14.0% by tonnage, and these typically have a working life of 14.0 years. Lastly, the remaining 51.4% are other ships (11.5% of the total by tonnage). The relatively short lifespan of bulk and container carriers is explained by the heavy and growing demand for these services, which has meant that the number of these vessels has expanded more rapidly than have other types of ship. With regard to national fleet sizes, the 5 largest are China (including Hong Kong SAR, which accounts for 19.1% of the global fleet), Greece (16.9%), Japan (10.4%), Singapore (6.3%), and South Korea (4.2%). Together these 5 countries therefore control 56.9% of the world’s shipping fleets. By comparison, with 0.2% of the total, Thailand sits in 152nd place in the world rankings.

The importance of Thailand’s maritime freight industry has been building steadily, helped by a number of factors. (i) The Thai economy is heavily reliant on export, accounting 65.4% of GDP in 2023. More than 83% of imported and exported goods primarily use maritime transport. (ii) Thailand has signed a range of free trade agreements that aim to increase trade and investment flows between members. These include the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). (iii) Thailand is host to production facilities that are integrated into the global supply chains of major industries, (e.g., the production of autos and auto parts). (iv) To help develop the competitiveness of Thai industry and trade, the government plans to develop the infrastructure required to support greater use of sea and coastal freight services.

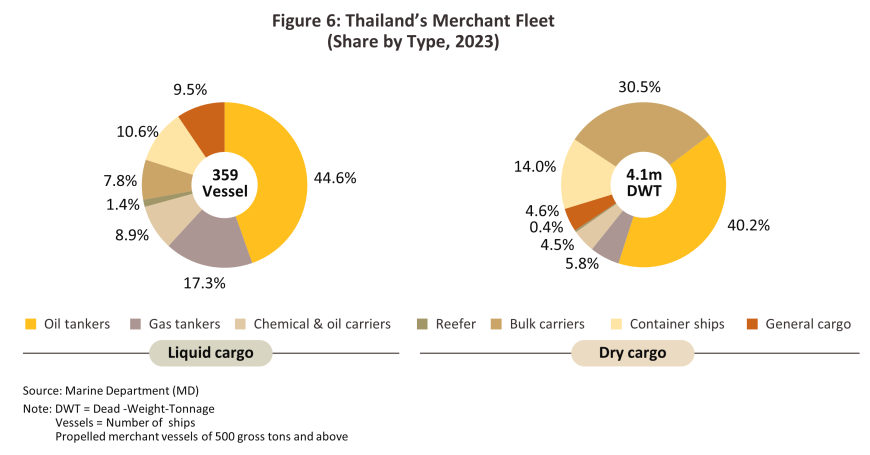

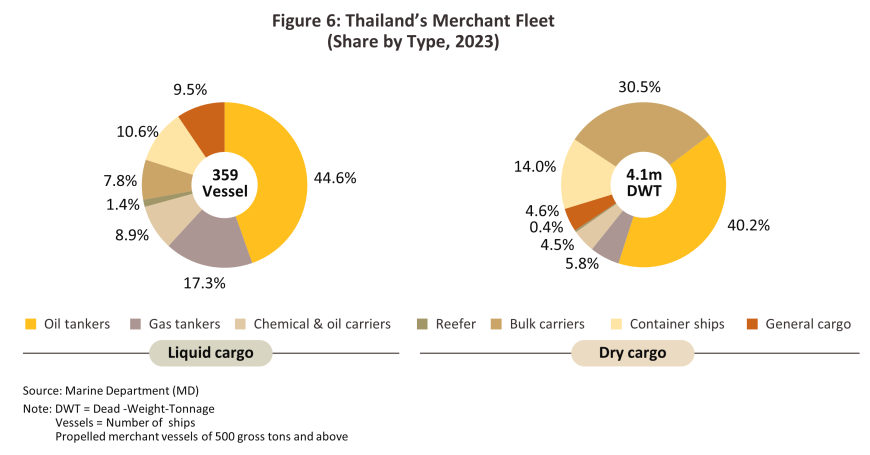

The Thai merchant fleet may be divided into two main groups6/ (Figure 6):

1) Liquid cargo ships: Thai companies operate 254 vessels in this class, and these have a combined capacity 2.1 million DWT (respectively 70.8% and 50.6% of the total national merchant fleet). These are divided into, 160 oil tankers, 62 gas tankers, and 32 chemical and oil tankers transporting chemicals and oil products. The main customers for the services provided by these are principally operators of oil refineries and major oil importers, which generally have oil storage facilities in coastal areas, as well as overseas manufacturers and distributors. Cargo is typically crude, chemicals, liquid refinery products, natural gas, and vegetable oils.

2) Dry cargo ships: The Thai merchant fleet includes 105 dry cargo vessels with a total carrying capacity of 2.0 million DWT (29.2% and 49.4% of the total, respectively). This includes (i) 34 general cargo ships (56% have a capacity not greater than 5,000 DWT) account for 9.3% of the total capacity of Thailand’s dry cargo fleet; (ii) 28 dry bulk carriers (96% of these have a tonnage in excess of 20,000 DWT) represent 61.6% of total capacity in this class; (iii) 38 container ships (68% have a cargo capacity not exceeding 5,000 DWT, the rest are large ships with a cargo capacity exceeding 10,000 DWT) account for 28.3% of total capacity and (iv) 5 reefer container ships (a capacity under 5,000 DWT) account for just 0.8% of total capacity. Thai general cargo ships and reefer container ships are generally relatively small since they are used as feeder vessels between coastal ports and large vessels call at deep-water ports or transshipping goods over short distances to neighboring countries.

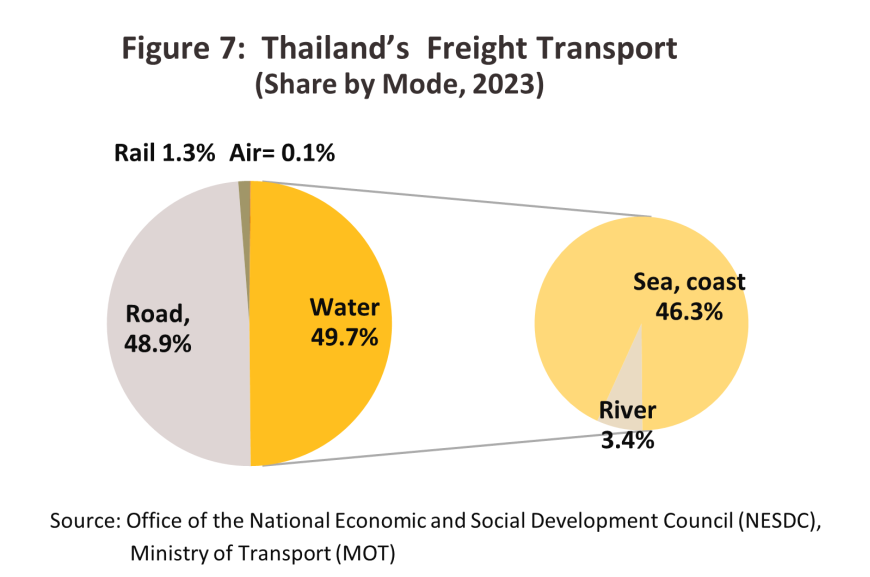

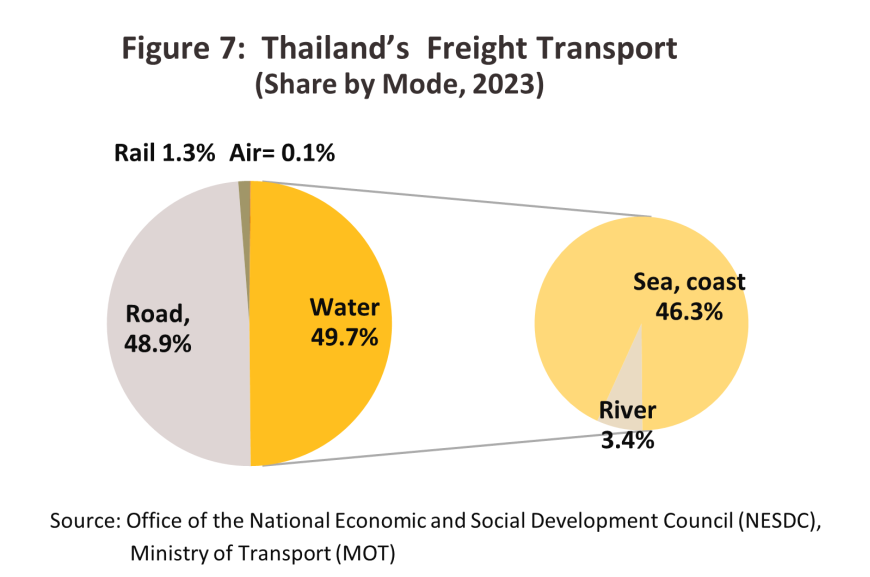

By volume, 49.7% of domestic shipments are made by waterborne transport (Figure 7), shipment cost per unit for water transport are lower than for any other modality (Table 2). Coastal and open-water shipping accounts for 46.3% of the total freight transport of Thailand, with inland (i.e., rivers and canal) shipping adding another 3.4% to this. International shipping mostly passes through Thailand’s major ports, that is, Bangkok (Khlong Toei), Laem Chabang, and Map Ta Phut, though inland facilities in, for example, Rayong, Songkhla, Chiang Saen and Chiang Khong may be used when shipping goods between Thailand and neighboring countries.

Thai operators are, however, somewhat uncompetitive on world markets. (i) The Thai merchant fleet is small, numbering only 359 vessels with a total tonnage of only 4.1 million DWT (source: Marine Department), or 0.2% of the total tonnage of the world fleet. This is because 71% of the Thai fleet, are classed as ‘small’ (i.e., they have a cargo capacity of less than 5,000 DWT) and only 11% of the total) are considered ‘large’, that is, they have a capacity in excess of 20,000 DWT. Thai-flagged carriers therefore carry a meagre 7% of Thailand’s international trade7/, most of which is intra-Asia trade, and so the remainder (93%) is carried by foreign shippers (generally European and Asian companies such as Chinese, Japanese and Korean). (ii) The Thai merchant fleet is largely old aged, which means that both maintenance and fuel costs are higher than they would otherwise be and this then negatively impacts the industry’s price competitiveness. For example, oil and gas tankers typically have a service life longer than 25 years, and for reefers, this extends to an average of over 30 years, (iii) The 20 largest liners sail span all over the world, of which, more than 55% of these is operated by just the 4 major liners (source: UNCTAD). These leading companies have expanded their service coverage by both forming strategic partnerships and diversifying into other transport modes, ensuring seamless logistics integration. For instance, Maersk has ventured into air freight through Maersk Air Cargo, while CMA CGM has merged its air freight operations with Bolloré Logistics. MSC has acquired Bolloré Africa Logistics to strengthen its port business in Africa, and Hapag-Lloyd has increased its investments in terminal operations in the U.S. and Latin America. Such developments allow these companies to meet global shipping demands across a wide range of routes. (iii) Compliance with increasingly stringent international regulations, particularly regarding the use of alternative fuels and carbon-reduction technologies in shipping (green technology), has become a growing cost burden for operators8/. Both Maersk and Hapag-Lloyd estimate that this will lead to an increase in vessel supply by 15% and 5-10%, respectively, in order to maintain service levels (source: UNCTAD). In 2022, newly built ships using alternative fuels such as LNG, batteries/hybrids, LPG, methanol, and hydrogen accounted for 21.1% of the global fleet. The Thai fleet has been gradually adapting to these regulations by utilizing fuel-efficient ships and installing equipment designed to reduce air pollution or treat wastewater before discharge into the sea.

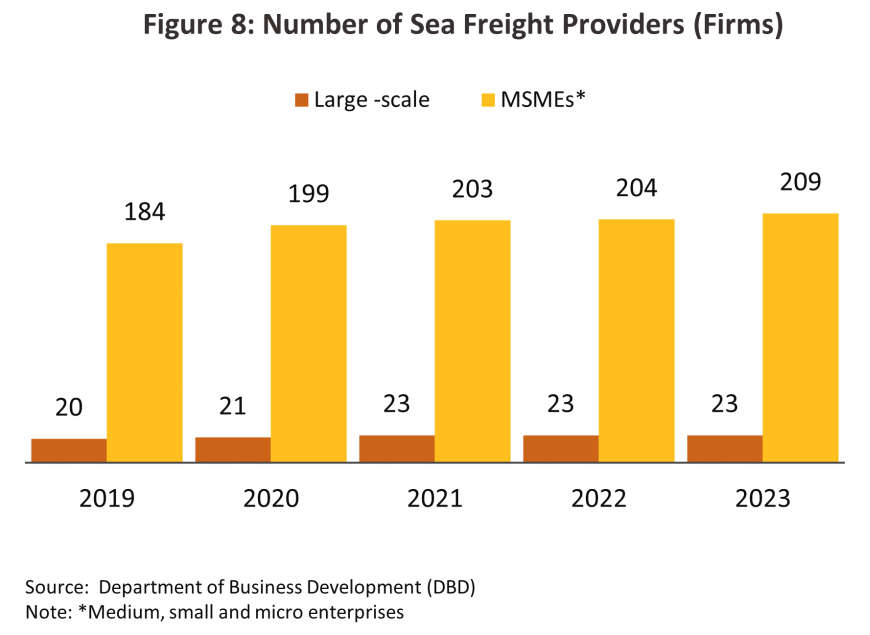

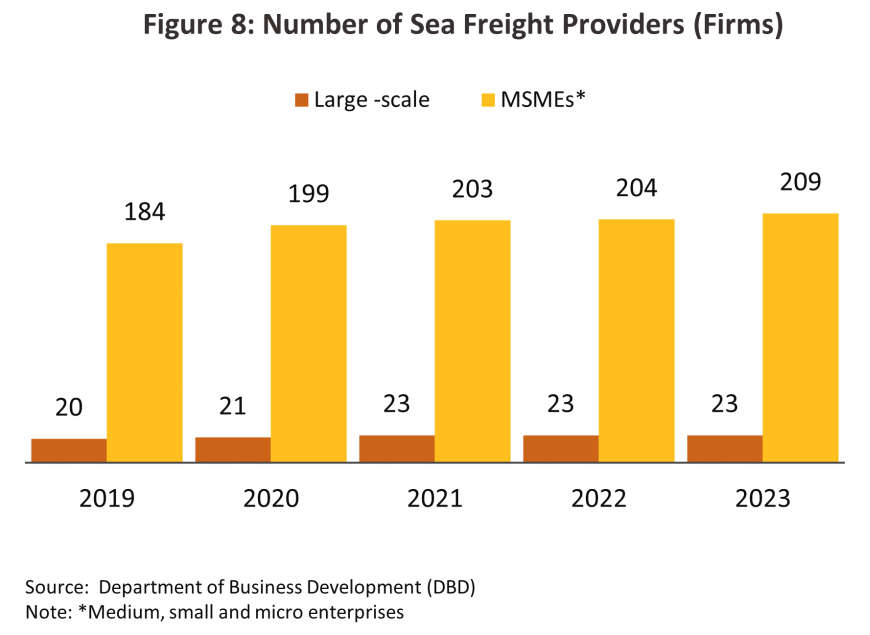

As of 2023, 232 companies (Thai or Thai-overseas joint ventures registered with the Ministry of Commerce) offered coastal or open water freight services (Figure 8). These can be classified into the following two groups. (i) 23 companies (6% of the total) are categorized as large operations9/, and most of these are Thai VOCCs of liquid cargos, containerized goods, bulk cargo services and joint ventures involving Thai companies. (ii) 209 companies are mediums, small and micro enterprises (94% of the total). This group10/ includes VOCCs moving liquid goods along the shoreline, bulk dry goods and containerized goods, and freight forwarders. Some of these are in fact subsidiaries of companies that transport products for affiliated companies, or are joint ventures with foreign countries in the countries where the vessels dock, or are subsidiaries of raw material producers.

Situation

Following a decline of -0.4% in 2022, global shipping volume returned to growth of 2.4% YoY in 2023. This improvement is explained by: (i) recovery in maritime supply chains following the ending of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has then helped delays to clear and seafreight rates to fall back to their normal range; (ii) earlier widespread drought that pushed some countries to limit food exports, and in response, demand for restocks rose on greater worries over threats to food security; and (iii) changes to shipping routes in Ukraine (namely the opening of the ‘humanitarian corridor’ on 10 August, 2022) that allowed the global supply of grains from Ukraine to return to close to its level prior to the country’s invasion in February 2022. Nevertheless, global trade contracted -1.1% in the year (source: WTO) as a result of the run up in inflation experienced worldwide, ongoing fighting in various parts of the world, and the emergence of El Niño conditions, which reduced water levels in the Panama Canal and many European domestic waterways. One consequence of this was that shippers were forced to reroute to avoid more dangerous areas (e.g., the Black Sea and the Red Sea) and to cut back on the frequency of sailings, adding to maritime transport times and, with surcharges rising (e.g., for insurance premiums and tolls) freight rates steepened. These increases were typically passed on to buyers of the goods being transported and so demand for items to hold in stock weakened, undercutting growth in sea freight services.

Global sea freight volume is expected to have risen by another 2.0% in 2024. Uptake of shipping services has been lifted by steady growth in the global economy that has then boosted demand for goods generally. In addition, Chinese companies have rushed to push through exports to the US ahead of increases in tariffs (up by between 25% and 102%), adding further to demand. However, these tailwinds have been somewhat offset by the geopolitical tensions in the Middle East and near the Red Sea from 19 November, 2023 onwards, which has then forced shippers to avoid these areas by sailing on more circuitous routes and added to portside congestion (e.g., in Singapore and across many Chinese ports). The market has also been hurt by periodic shortages of containers and falling shipping capacity, thereby adding to longer transport duration, and rising costs that have come as a result of more expensive fuel and an increase in insurance premiums and other operating costs. Given this, rates have undergone periodic volatility, significantly impacting the total quantity of goods that were freighted through the year.

Demand for Thai shipping is expected to have risen 2.5% by volume in 2024. The market has benefited from forecast growth of 2.7% in world trade (WTO), as well as from an acceleration of exports as demand switched from China to Thailand (e.g., for electronics and electrical appliances). The rush by some Chinese manufacturers to push through exports has also helped Thai players connected to these companies’ supply chains, while the decision by the government to allow 400-meter ships to dock in Thailand has added to tailwinds by boosting international trade volume and with this, demand for shipping services. Less positively, the above-described geopolitical tensions, periodic container shortages, and rising costs (which are ultimately passed through to final buyers) have restrained growth in consumer demand. Details of how the market has played out in 2024 are given below:

-

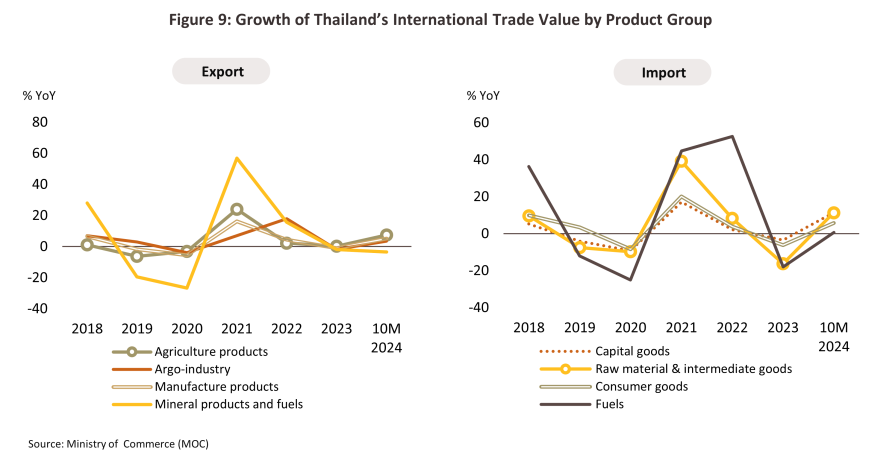

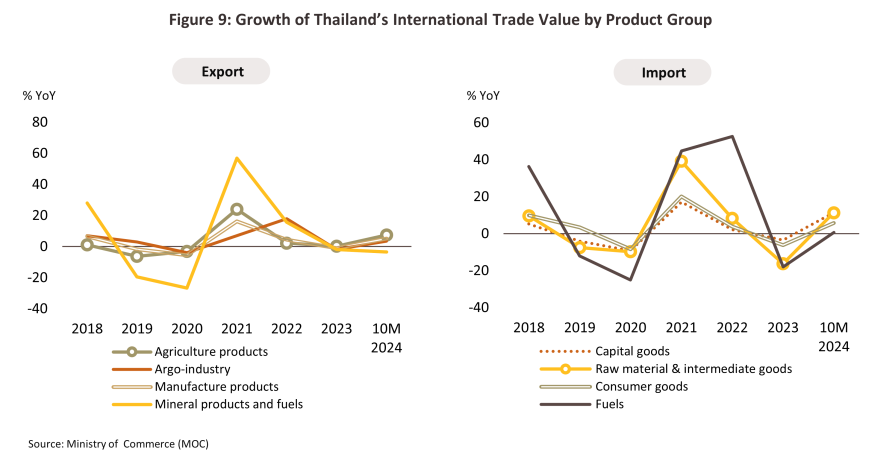

Overall international trade (imports and exports) is expected to expand by 4.3% YoY (in value terms), aligning with the global trade trends. In 10M24, (Figure 9) Export value expanded 4.9% YoY in the period, with growth recorded in agricultural exports (+7.4% YoY) and industrial goods (+5.3% YoY), while import value also climbed 6.5% YoY, led by capital goods (+11.4% YoY), raw material and intermediate goods (+11.3% YoY), and crude (+9.6% YoY). Bangkok and Laem Chabang remain the main ports for Thai shipping.

-

Krungsri Research analysis indicates that in 2024, the number of ships in operation rose 1.0-2.0%, moving in step with growth in international trade and the need to service routes linking to areas with high growth potential (e.g., India, the Middle East and Africa). In addition to extending these services, new ships will also replace older, outdated vessels by allowing energy-saving devices and other similar types of modern technology to be deployed (e.g., that allow for cuts to be made in the overall weight of the ship, less fuel to be used to maintain a given speed or to travel a given distance, and less CO2 to be emitted). At the same time, some Thai ships have been decommissioned, reregistered in different countries, or refitted to meet new international standards11/, but older vessels (those with an average working life of 37 years) have been scrapped.

-

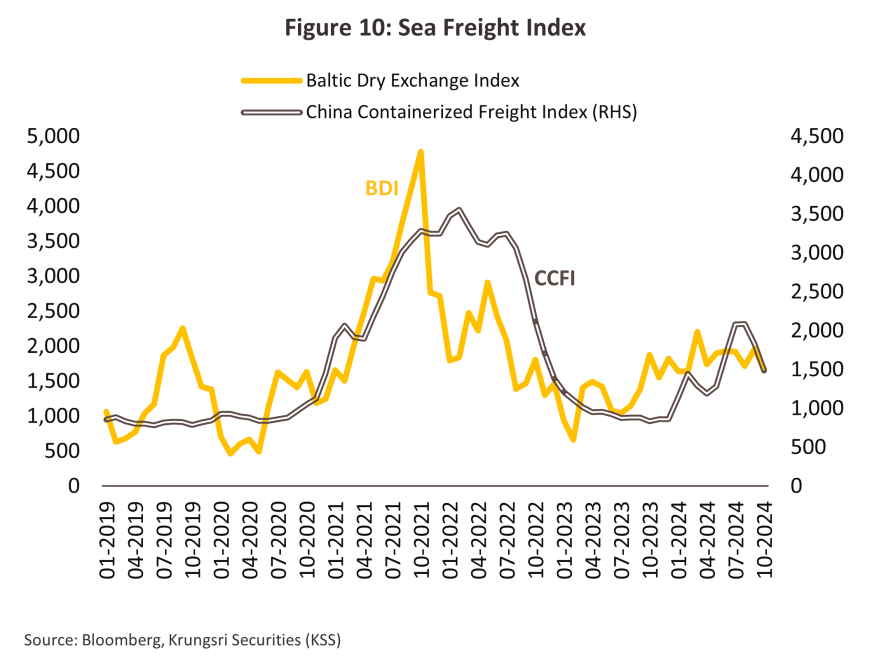

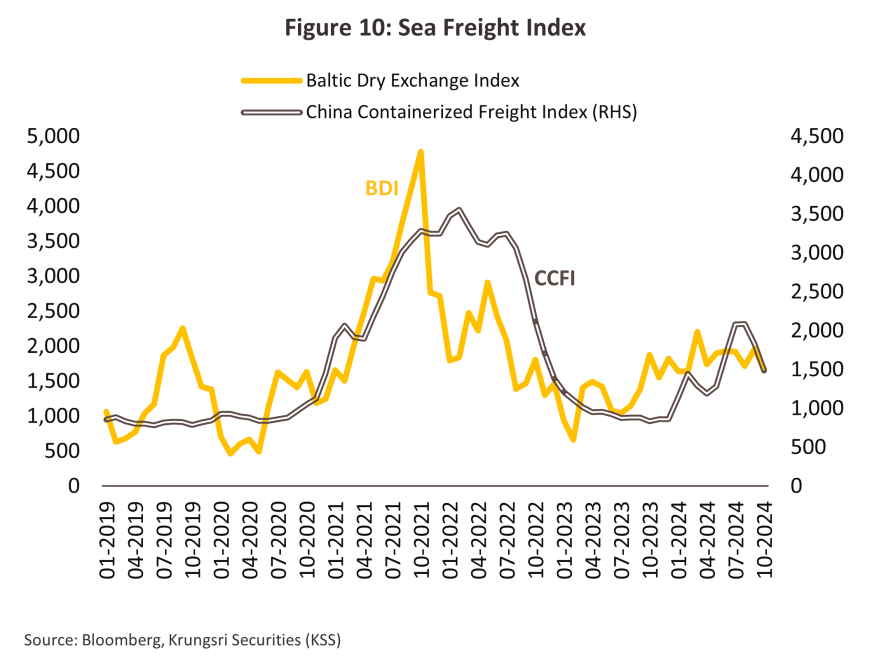

Freight rates climbed in 10M24, with the BDI and CCFI up by respectively 47.2% and 61.3% YoY (Figure 10) to hit highs of 2,205 (in March) and 2,086 (in August). Nevertheless, these peaks remained below the BDI’s and CCFI’s earlier COVID-era highs of respectively 4,782 in October 2021 and 3,557 in February 2022. In October 2024, freight rates for routes linking Thailand to major destinations increased across the board relative to their level prior to the start of the troubles in the Red Sea in 2023, and so for 20-foot containers, rates were up 218.2% YoY to Europe, 87.5% to the west coast of the US, 26.7% to India (Nhava Sheva), and 196.0% to Africa (Durban). Shipping costs thus climbed, with negative impacts on Thailand’s international trade volume.

Higher freight rates helped to lift performance through 1H24, and so for publicly traded sea freight companies, revenue rose 8.1% YoY for container shippers and 45.1% YoY for bulk shippers.

Outlook

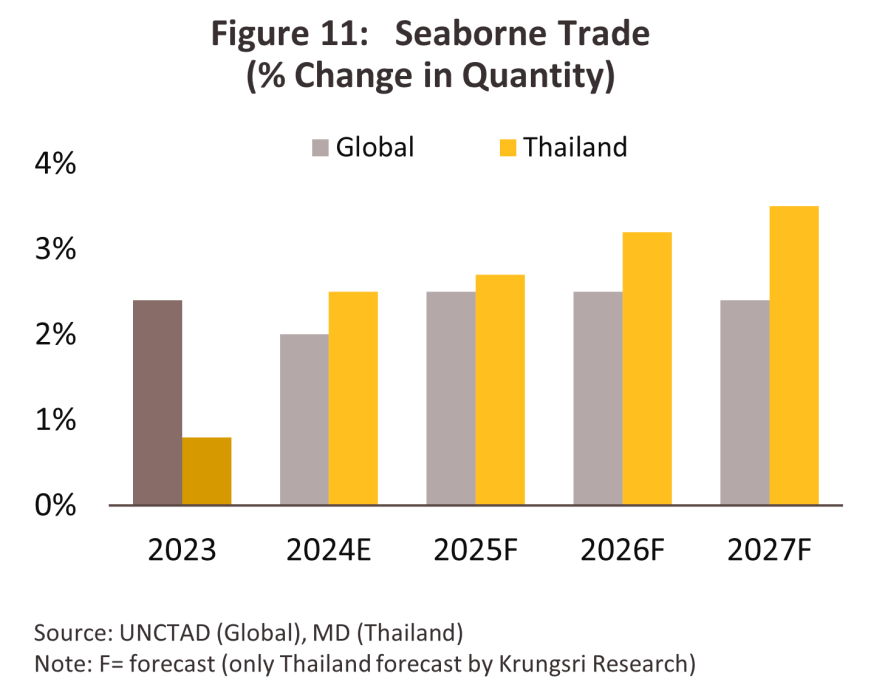

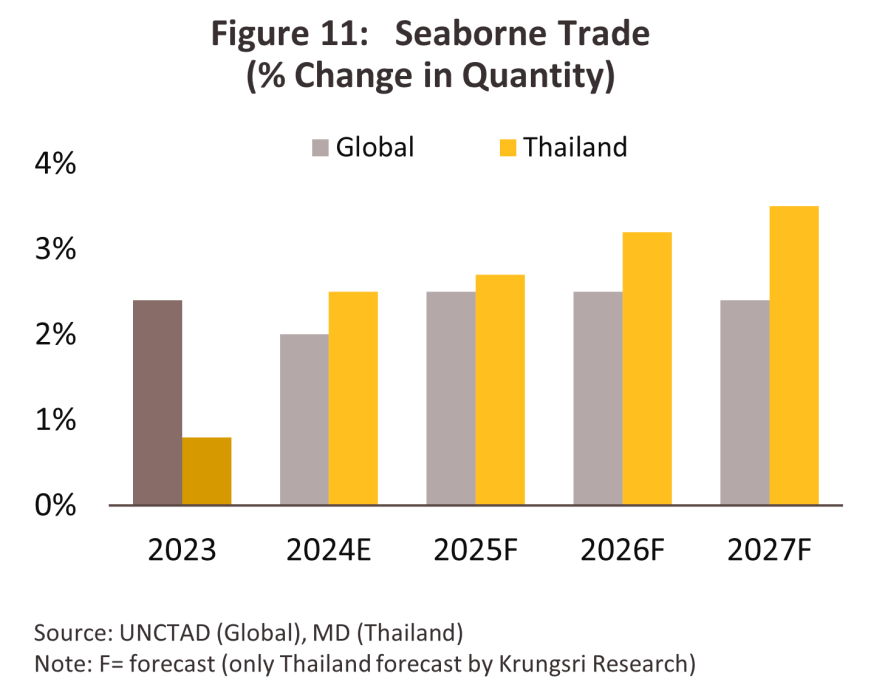

Against a backdrop of strengthening world trade, UNCTAD sees global seaborne volumes expanding by 2.5% in 2025, up slightly from 2024’s 2.0% (Figure 11). This will boost international trade with Thailand, and so Krungsri Research expects that demand for Thai seaborne will grow at an average rate of 2.5-3.5% annually over 2025-2027, up slightly from growth of 2.7% in 2024. Factors supporting this outlook will include the following.

-

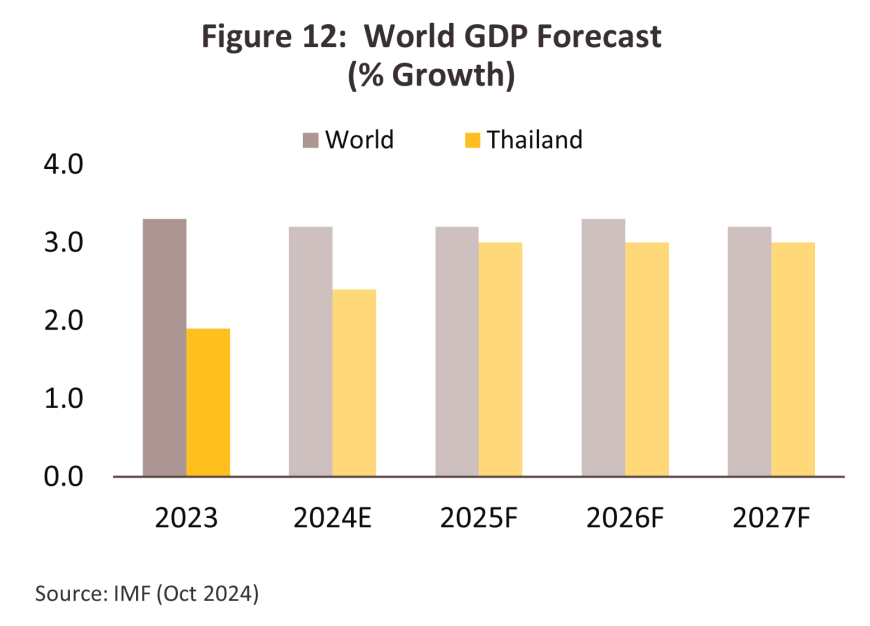

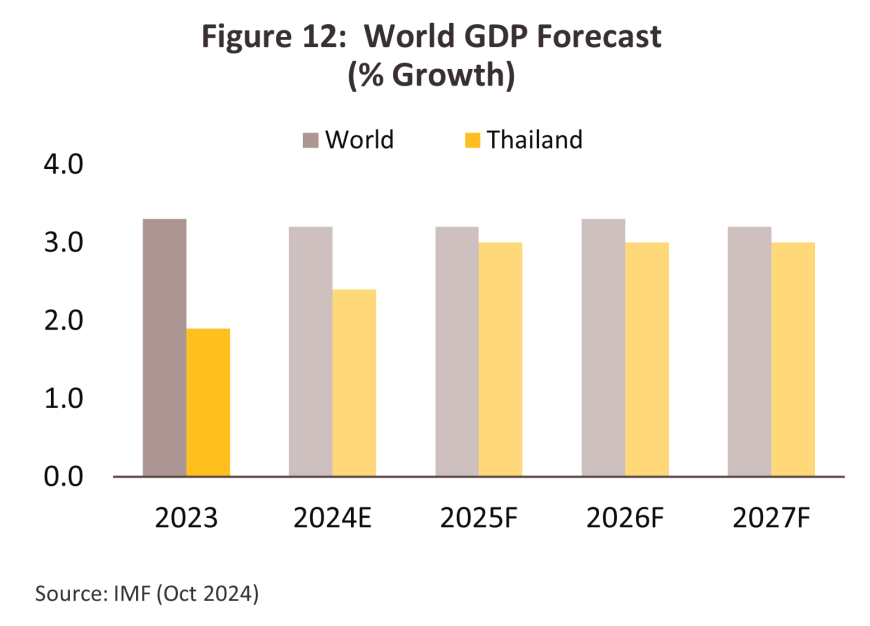

Global economic growth is projected to recover gradually, with the IMF sees averaging 3.2% annually over 2025-2027, will boost global trade by some 3.3-3.6% per year, up slightly from 3.1% in 2024 (Figure 12). This will be especially strong in Asia (which accounts for more than 53% of all global maritime shipping), and so the IMF expects regional growth to hit 4.6-5.0%. The outlook will benefit further from Asia’s integrated rail and maritime transportation networks, which partly thanks to the Belt and Road Initiative now link the region to Africa and Europe.

-

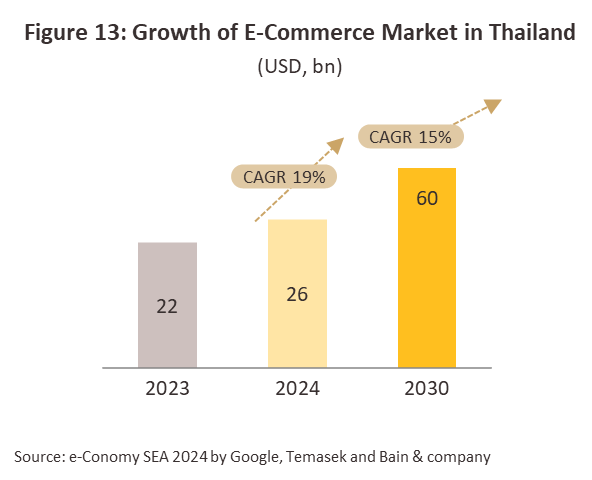

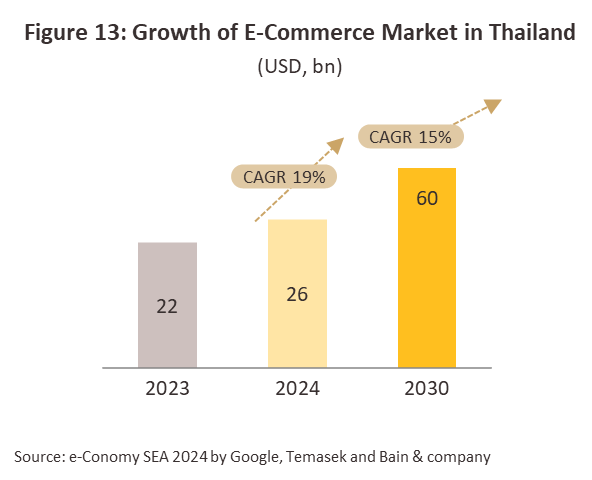

The Thai economy is forecast to grow by 2.5-3.0% annually. This growth will be driven by a robust recovery in the tourism sector, with foreign arrivals expected to exceed 40 million in 2025, increasing demand for consumer goods. Additionally, Thailand will benefit from trade diversion and the acceleration of export market expansion in the Middle East and Africa following escalating U.S.-China trade tensions. Moreover, accelerating climate change and geopolitical stresses are raising concerns over food security, boosting global demand for foodstuffs. Given Thailand’s role as a major supplier of agricultural goods to world markets, the country will benefit from these trends. A further boost will come from the forecasted 15.0% per annum expansion in the e-commerce sector (source: e-Conomy SEA 2024) (Figure 13), which will increase the uptake of shipping services to meet demand from both domestic and international consumers. Given these factors, demand for maritime freight services for the shipping of consumer goods, raw materials, machinery, and equipment is expected to strengthen.

-

The global trade environment is evolving, with decoupling of supply chains becoming more evident and trade barriers intensifying, especially between the US and China. As a result, Thailand is increasingly attracting foreign investors relocating their production bases, leveraging its strategic location in the center of the ASEAN region, the advanced infrastructure, and ongoing investment promotion schemes (e.g., the Board of Investment strategic plan for investment promotion for 2024-2027. In addition, Thailand has concluded a number of bilateral and multilateral trade agreements that have opened up further opportunities for Thai shippers to grow and diversify their markets, routes and revenue streams (currently, officials are negotiating FTAs with the United Arab Emirates and the European Free Trade Association).

-

Government plans for the development of maritime infrastructure will help to integrate intermodal logistics operations, thereby accelerating the speed of freight services. This will be especially significant in the Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC), where important projects include the following: (i) Phase 3 of the Laem Chabang Port development will expand the site’s container handling facilities by 7 million TEU annually (this will come onstream gradually over 2027-2035). (ii) Phase 3 of the Map Ta Phut Port development will extend annual petrochemicals and natural gas capacity by 16 million tonnes, and this will make it a center for the trade in liquified natural gas (LNG) within the ASEAN region (the first section of this should open for commercial operations in 2026). (iii) Other spending on multimodal services includes phase 2 of the construction of the Laem Chabang rail transshipment center, where electric cranes are being installed to facilitate ship-to-rail-to-road container transfers, and the development of regional ports to support Krabi-Phang Nga-Phuket freight routes (work on this will run over 2024-2033).

-

Trade opportunities will be multiplied by the development of transportation routes that better connect Thailand to its neighbors. As part of this, China’s New International Land and Sea Trade Corridor (2023-2027) will link to the earlier Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to connect Thailand and the broader ASEAN region to Qinzhou Port by sea. In particular, this will support the development of a sea-rail modal link that thanks to integration with the China-Europe railway will then facilitate shipping to the Central Asia and Europe. As a result, Thai companies are now seeing improved opportunities for exporting to Qinzhou from Bangkok and Laem Chabang ports (these have transit times of respectively 5 and 6 days). More broadly, given the general uptick in demand for global shipping and the strategic importance of ASEAN sea routes in connecting East Asia to the rest of the world, many nations in Southeast Asia are spending heavily on maritime megaprojects.

Factors tending to undercut growth in revenue for Thai sea freight operators will include the following. (i) Freight rates may see periodic spikes as a result of ongoing geopolitical stresses that may worsen at times. If this happens in or near areas that are important sea routes (e.g., in the Red Sea), costs will be driven up. Alongside this, the adoption of protectionist measures by major economies (e.g., the US, the EU, and Canada) that target Chinese imports may also drag on growth in Thai exports. (ii) Competition between shippers is expected to intensify following the decision by Maersk (the world’s 2nd largest shipper) to abandon its agreement to cooperate with MSC (the world’s largest shipper) after January 2025, and so from February, Maersk will work with Hapag Lloyd (5th) within ‘The Gemini Cooperation’ network. At the same time, ‘The Ocean Alliance’, which brings together CMA CGM (the world’s 3rd most important shipper), COSCO (4th), Evergreen (7th) and OOCL (part of the COSCO group), has agreed to extend cooperation until 2032, while ‘The Premier Alliance’, which consists of ONE (6th), HMM (8th) and YML (9th) plans to expand its trans-Pacific and Asia-Middle East operations. These commercial alliances have significant market power and because of their size, they are able to determine rates. Thai players may therefore be at risk of seeing their market share diminish. (iii) Growth in the supply of shipping capacity may outpace the rise in demand. Thus, BIMCO estimates that in 2024 and 2025, container shipping capacity will rise by 10.3% and 6.3%, with fleet sizes growing by an average of 6.7% per year against annual demand growth of 5.5%. Similarly, Drewry Maritime Research sees bulk capacity expanding by 2.7% and 2.4% in each of these two years, while demand will be up by 1.5-3.0%.

Going forward, Thai players are expected to respond to rising demand by adding 1.0-2.0% to capacity per year. In addition, shippers will be motivated to invest in new vessels by the prospect of expanding into new routes and so extending their income base. Thai companies will also adjust their playbooks by offering a greater range of intermodal transport services and by partnering with foreign companies to open up the possibility of laying on new services and attracting new customers. Nevertheless, Thai companies will have to contend with stiffening competition from new and existing overseas players. These are being attracted to the market by the importance of the trans-Pacific and Asia-Europe lines to Asian-western trade, and these are therefore hoping to expand into Thai markets. For example, from November 2024, the Chinese Sinolines has offered freight services connecting Thailand, China, and Hong Kong, while Corten Shipping (Thailand) a global leader within the maritime freight market, is also now active in domestic markets. In addition, the maritime regulations mandating reduced CO2 emissions have forced cargo ship operators to adapt their operations, for example by using newer or younger vessels, reducing shipping capacity or limiting cargo loads, and slowing down vessels’ speed. These measures have in turn kept freight rates above their pre-pandemic average.

The outlook for the industry will vary by segment, as described below:

-

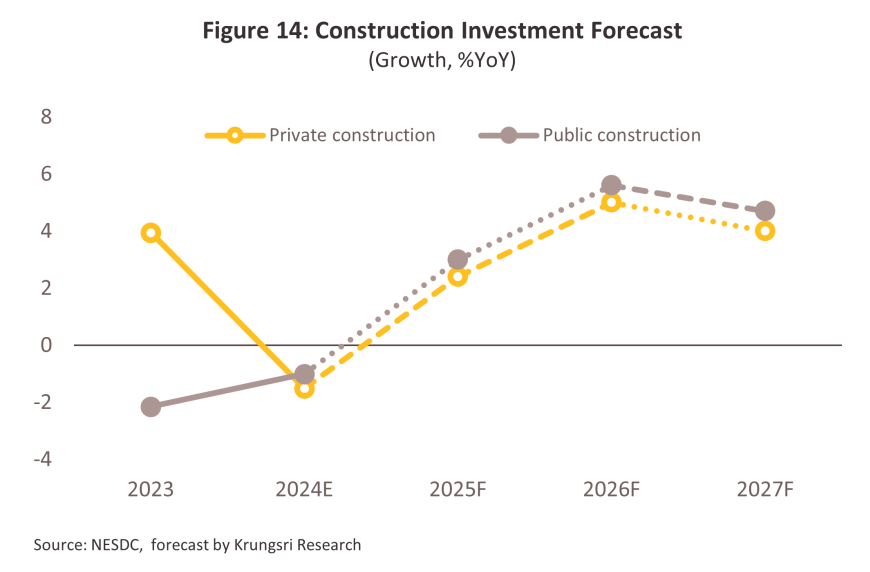

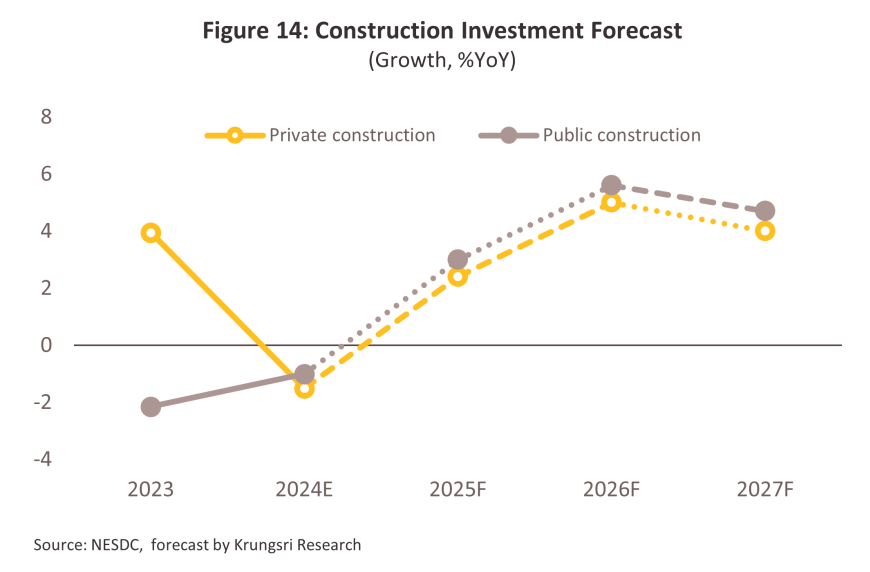

Containerized shipping: Business conditions will improve thanks to economic growth and the resulting rise in domestic spending power, expansion in the construction sector (public- and private-sector spending on construction is forecast to rise by respectively 4.5% and 3.8% per year) (Figure 14), and the continuing growth of the e-commerce industry. This will then lift demand for a broad range of items, including consumer products, industrial goods, agricultural and agro-processing products (chilled and frozen processed goods, and processed foods) equipment and machinery, and other miscellaneous items.

-

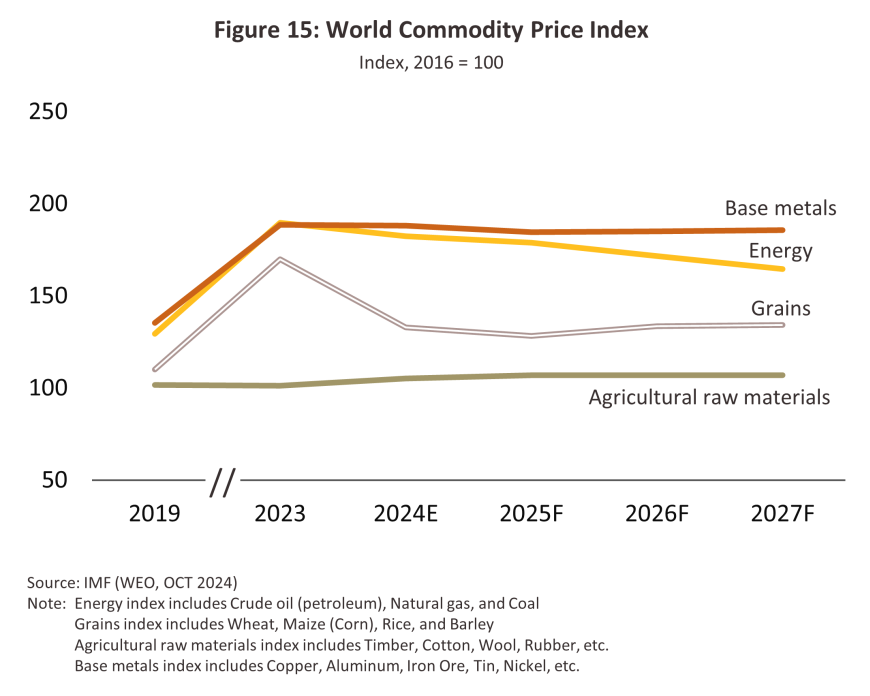

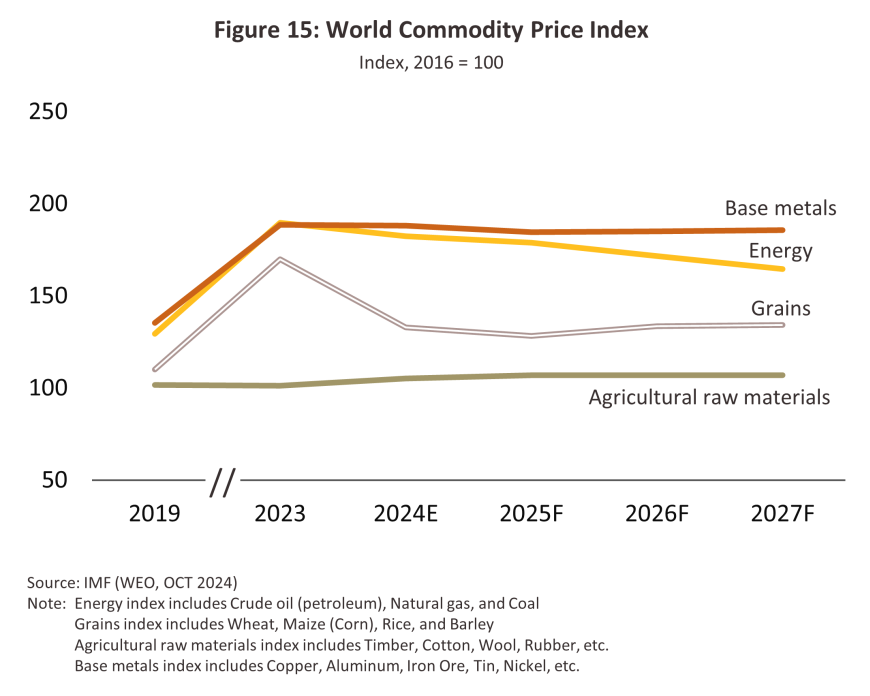

Bulk shipping: Turnover will rise slowly in step with rising demand for commodities, construction materials, and metals and ores. This is showing up in: (i) commodity price indices for many goods that remain above their COVID-19 averages (Figure 15); and (ii) greater demand for food and agricultural products, partly as a result of the impacts of severe weather (drought, heatwaves, and flooding) on outputs that has then eroded food security in many countries. Indeed, the UN’s Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) sees global outputs falling for wheat, rice, and maize, and this will boost demand for agricultural goods and food to stockpile in case of future shortages.

-

Tankers (chemicals, gases, and petroleum products): Demand for tanker space will expand in line with growth in the economy since the latter will drive additional consumption of oil and gas by the industrial, transportation and power generation sectors. Krungsri Research expects that domestic demand for refined products will expand by 2.0-3.0% per year over 2025-2027 from its 2024 level of 150.0-160.0 liters/day.

Going forward, Over the next few years, challenges that may weigh on turnover will include the following. (i) Widespread geopolitical tensions are pushing up prices for crude and adding to transportation costs. (ii) Competition from overseas shippers will likely intensify as these expand deeper into markets in Asia. Because these players occupy a significant market share and control a major fraction of total capacity, they are able to negotiate from a position of strength. Thai operators will thus need to rapidly raise their competitiveness by, for example, partnering with other companies to cut their costs and increase the efficiency of their management systems. (iii) Investment costs will rise with the need to meet more stringent international maritime standards, in particular those that have a bearing on fuel efficiency and the use of new transport technologies. Players will also need to bring their ships up to ‘zero emission vessel’ standards as required by IMO 202312/ (i.e., by reducing greenhouse gas emissions from these) but both next-generation low-carbon ships and alternative fuels are expensive and in limited supply. (iv) Delays in work on government-backed maritime infrastructure will affect expansion in the industry, with many projects still undergoing feasibility studies. This includes initial work on phase 3 of the Laem Chabang Port development (the F1 wharf is due to open in 2027) and the first section of phase 3 of the Map Ta Phut Port work, now scheduled to begin commercial operations in 2026. (v) The market space open to the commercial use of smaller vessels is narrowing (source: Alphaliner). Since much of the Thai merchant fleet is made up of smaller, older ships, this poses a threat to the industry. Players may therefore have to endure intense competition over freight rates from similar sized, larger, and newly constructed ships as these steadily enter service.

1/ Source: Office of Transport and Traffic Policy and Planning (OTP), Ministry of Transport (2013)

2/ United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD)

3/ Not include fisheries products from fishing boats, ships carrying aircraft, arms and armaments, and coastguards and rescue vessels.

4/ Dry cargoes include bulk cargo such as grains, coal or iron ore. General cargoes, such as raw materials, semi-finished goods or finished goods, machinery, breakbulk cargo, and refrigerated goods.

5/ Goods may be carried as a ‘full container load’ (FCL) or as a ‘less than a full container load’ (LCL).

6/ As of 2023. Data supplied by the Office of Maritime Promotion, which operates within the Marine Department.

7/ Construction of the canal system linking the Pacific and Indian oceans in the south of Thailand: Annex E of the Development of the National Logistics System, published in 2015 by the Secretariat of the House of Representatives.Compliance with the Energy Efficiency Existing Ship Index (EEXI) and Carbon Intensity Indicator (CII) standards set by the IMO is expected to result in reduced sailing speeds to improve pollution reduction efficiency.

8/ Compliance with the Energy Efficiency Existing Ship Index (EEXI) and Carbon Intensity Indicator (CII) standards set by the IMO is expected to result in reduced sailing speeds to improve pollution reduction efficiency.

9/ Shippers of liquid cargos include Siam Lucky Marine (subsidiaries of the Siam Gas and Petrochemicals), Ama Marine, VL Enterprise, and Nathalin Group. Shippers of containerized goods are Regional Container Lines. Shippers offer bulk cargo services are the Precious Shipping, TASCO Shipping and Bitumen Marine (shipped asphalt and coal for TASCO Group). The joint ventures involving Thai companies include Gulf Agency Company (Thailand-Liechtenstein) and Thoresen Shipping (Thailand-Singapore), and the international company is Shipco Transport (Thailand) (Denmark-Singapore).

10/ Companies in this category includes the Precious Shipping Group, Bio Green Energy Tech Group, Leo Global Logistics Group, Thai Oil Group, Thai International Tanker Oil Group, subsidiaries of Susco, United Standard Terminal (a Mitr Phol Group affiliate), Alpha Maritime Company (a Tipco Asphalt Group affiliate), and Thitti Phumi Company (an affiliate of RCL).

11/ As of 1 January 2023, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) has enforced amendments to the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL) that tighten earlier regulations. These include the Energy Efficiency Existing Ships Index (EEXI) and the Carbon Intensity Indicator (CII), which aim to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases and to ensure the use of low-sulfur fuels. The regulations are enforced according to a vessel’s engine capacity, tonnage, and speed, and in addition to affecting operations, these new rules will also hasten the scrapping of vessels that have been in service for more than 25 years.

12/ IMO 2023 (the 2023 IMO GHG Strategy) requires that sea freight companies reach net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, with intermediate targets set for 20-30% reductions by 2030 and 70-80% cuts by 2040.

.webp.aspx)