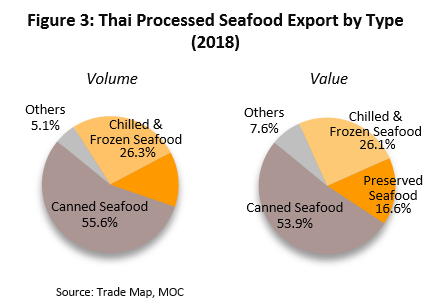

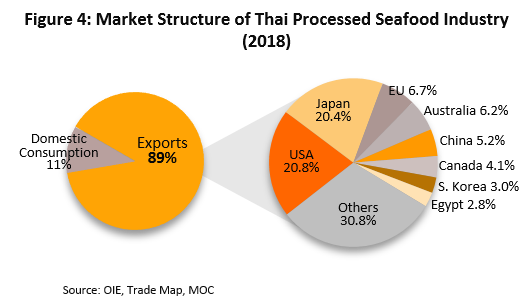

The Thai processed seafood industry will see annual growth limited to rates of just 1-2% in the period 2019 to 2021. Exports (89% of all production by volume) are expected to encounter rising competition on global exchanges, while Thailand’s main trading partners will also tend to step up their own output of seafood products and to raise the level of intra-regional trade that they are engaged in. More positively, the domestic market (11% of output) will benefit from rising consumption that will be underpinned by continuing urbanization, growth in the restaurant sector (especially of fast-food outlets), and modern lifestyles that tend to emphasize consumption of food that is quick and easy to prepare.

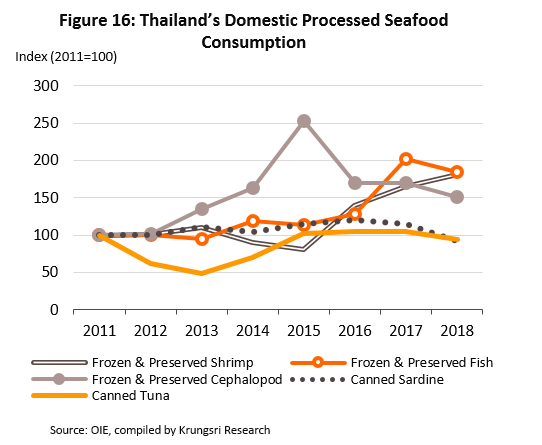

The 11% of production that is not bound for export is consumed domestically but because Thai consumers typically prefer fresh seafood, the market is largely limited to relatively inexpensive canned sardines and mackerel, while other types of processed seafood may be consumed by the fast-food sector, restaurants and hotels. However, despite this, demand for processed seafood within the country is growing in step with continuing urbanization and changing consumer behavior that is tending to strengthen demand for food that is quick and easy to prepare, and this is then helping to increase the volume of products distributed through modern retail outlets.

The chilled and frozen seafood industry

In 2017, global exports of chilled and frozen seafood came to USD 110 bn and the world’s five most important exporters were China, Norway, India, Vietnam and the U.S.A. (table 2), which by value together exported around a third of all chilled and frozen seafood globally. For its part, Thailand was in 16th place in this ranking of exporters. The most important products within the segment are as follows.

- Chilled and frozen fish (fresh fish, both whole and filleted): Exports of these goods have a value of USD 67 bn, or 60.6% of the value of exports of all chilled and frozen seafood globally. The most important exporters are European (47.3% of the value of exports of chilled and frozen fish worldwide) but most of this trade is intra-regional and so Europe is also the world’s leading importer of chilled and frozen fish, with a 43.4% share. In terms of value, the next most important exporters are China (10.8%) and the U.S.A. (5.5%). Thailand is in 29th position on this list and the country has a 0.7% share of the world market.

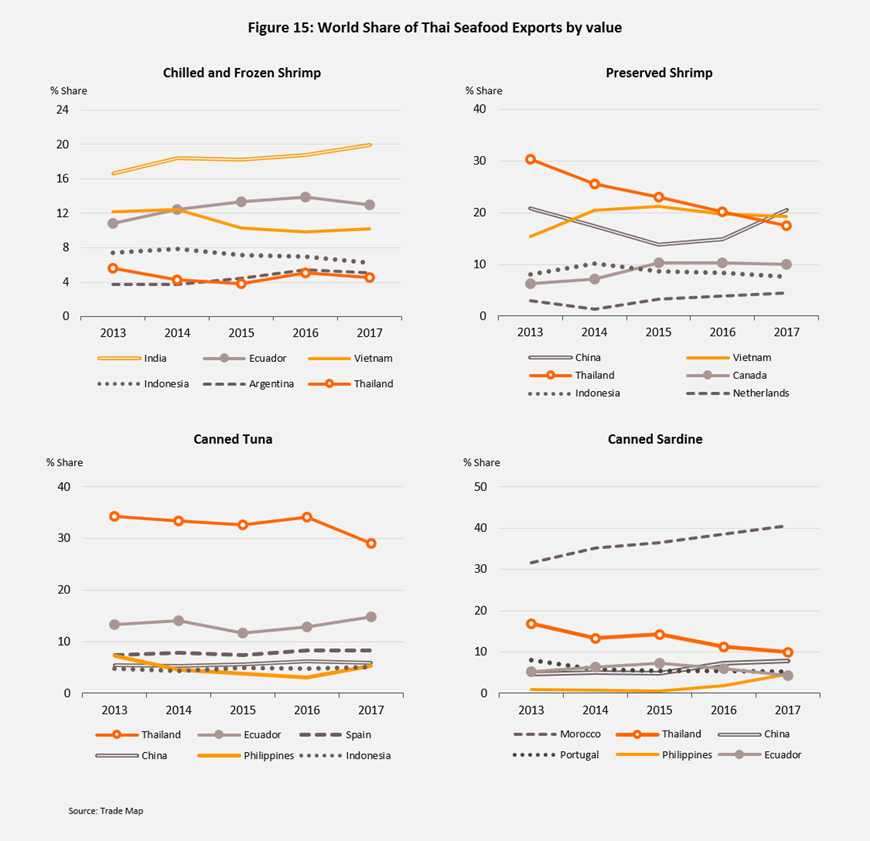

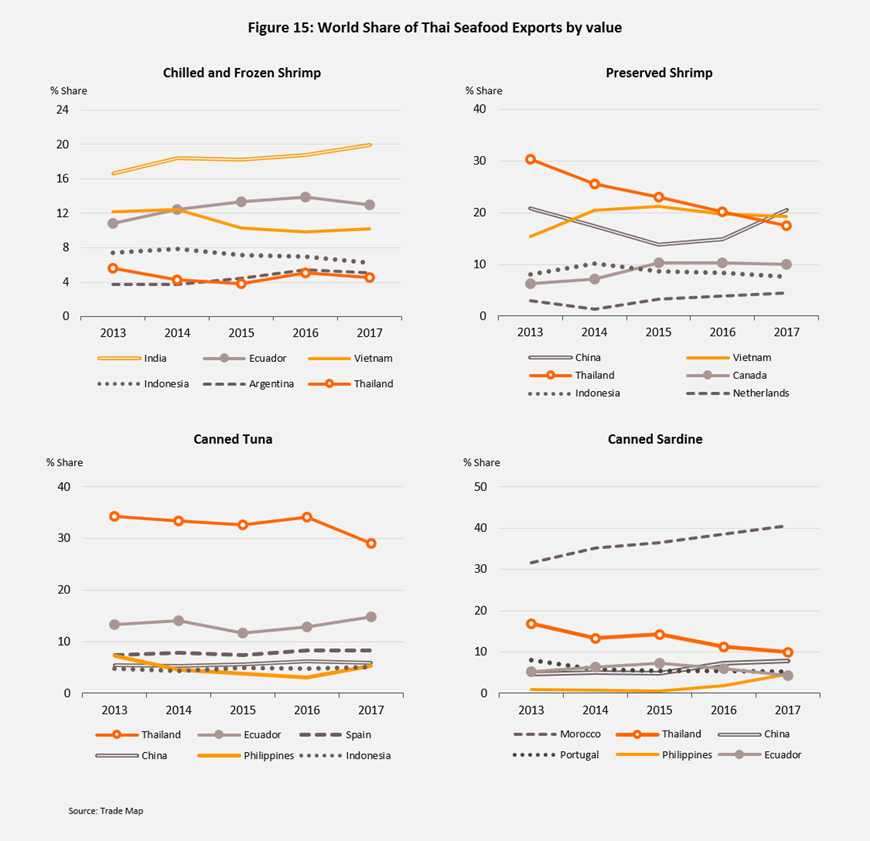

- Chilled and frozen shrimp: Global exports of these goods generate earnings of around USD 23 bn and account for a further 21.1% of the value of all exports of chilled and frozen seafood. The main exporters are in the Asia region (51.4% of all exports by value) and include India (20.0%), Vietnam (10.2%), Indonesia (6.2%), Thailand (4.5%) and China (4.4%). Outside Asia, the most important exporters are Ecuador (13.0%) and Argentina (5.1%).

- Chilled and frozen cephalopods: The last major product group in this segment, chilled and frozen cephalopods brings in USD 9.0 bn in export earnings, or 8.1% of the value of the segment. The main exporters of chilled and frozen squid are China (29.2% of the value of all exports worldwide), Spain (9.0%), Morocco (9.0%) and India (8.4%). Thailand has a 3.9% share of the world market.

Within Thailand, operators involved in chilled and frozen seafood (figure 5) may produce a number of separate products as the procedures and processes required for each are not significantly different. The most important of these products are given below.

- Chilled and frozen shrimp: In 2018, sales to export and domestic markets combined had a value of USD 988 m[3], or 50.7% of the value and 29.2% of the volume of all sales of Thai chilled and frozen seafood. Because it has related upstream industries within the country, including shrimp hatcheries, nurseries and farms (most of which are raising Pacific white shrimp), shrimp processing has a longer, more involved supply chain than do other chilled and frozen seafood products[4] but this generally guarantees a supply that is sufficient to meet demand for fresh and processed shrimp. In addition, Thai players also benefit from the skill of local labor and the access that large Thai companies have to modern production technology when processing for export. Thailand’s image is also generally positive and the country is regarded as a source of high-quality and most importantly safe produce. However, in the period 2011-2016, producers were affected by the spread of shrimp early mortality syndrome (EMS)[5] and this caused a sharp drop in yields, leading to a fall in exports of chilled and frozen shrimp. The latest figures for 2018 show that, at 27.8% of the total, the contribution of shrimp to total exports of chilled and frozen seafood is now sharply down on the 2011 figure of 56.1%.

- Chilled and frozen fish and cephalopods: The fish portion of this segment is worth a 28.1% share of the value of all chilled and frozen seafood in Thailand, or 58.8% of the market by quantity, while by value and quantity respectively, cephalopods are responsible for a further 21.6% and 13.4%. Because most of the more popular types of fish[6] are deep-water species that are not native to Thai waters, most inputs to processing facilities are imported and then prepared and frozen in Thailand for re-export. The most important sources of these imports are China, Taiwan, India and the U.S.A..

The state of the domestic seafood processing industry depends on the value of the Thai baht and on the price of oil, which together have an important influence on the cost of importing inputs. In addition, the stability of the catch size is also important, although changing climatic patterns brought on by climate change are now causing catch sizes to fall and in response, governments are instituting increasingly tight regulations on the activities of trawlers operating in their waters, including the imposition of quotas and enforcing no-catch periods.

Canned seafood, prepared and preserved seafood industry

In 2017, the world market for exports of Canned seafood, prepared and preserved seafood had a value of USD 34 bn. The major exporters were China, Thailand, Vietnam, Poland and Germany (Table 4) but considered in terms of product groups, (i) exports of products made from fish (65.8% of the value of all global exports of canned seafood, prepared and preserved seafood) were led by China and Thailand, with market shares of respectively 16.1% and 12.3%, while (ii) exports of products made from shrimp, cephalopods and other seafood were again dominated by China (a 35.1% share), followed by Vietnam (14.0%) and Thailand (9.3%).

More locally, Thailand is relatively competitive in world markets for shrimp, and for canned, prepared and preserved fish. Most of the latter (much of which is tuna) is imported as fresh, chilled produce, with a lesser amount originating from the catch made by Thai trawlers, the majority of which are in fleets operated by major seafood processors. Likewise, cephalopods (largely squid) are in the main imported, with a smaller quantity coming from Thai sources, while on the other hand, shrimp, mostly White pacific shrimp, is normally sourced from farms within Thailand. Seafood supply chains in this segment are also linked to many other related industries, such as producers of vegetable oil, sauces, food ingredients and flavorings, and cans.

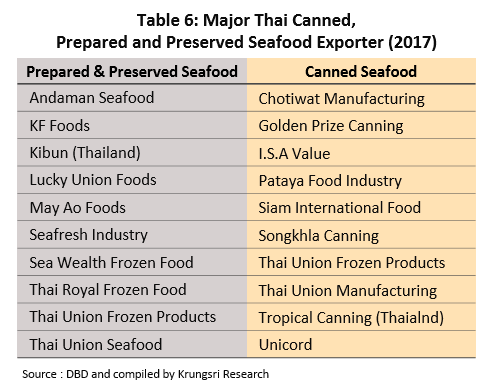

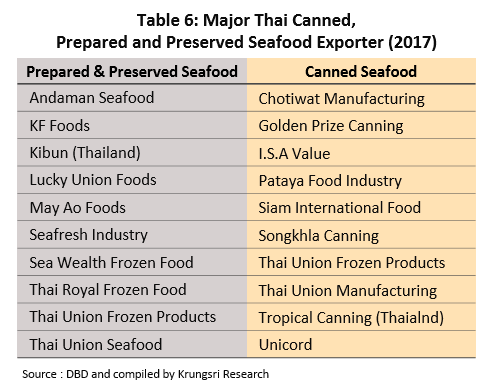

- Canned seafood: This is the most prominent part of Thailand’s seafood processing sector. Canned seafood products (including canned fish, shrimp and other types of seafood) generate the greatest annual sales of any seafood exports and canned tuna has been the leading product within the sector for the past 17 years, with Thailand’s share of the market coming to 29.0% of all global sales of canned tuna (as of 2017). The major operator in this area is Thai Union Group (TU), which has expanded its operations into Europe and the U.S.A., and is regarded as the world’s most important producer of tinned tuna. In addition, Thailand is also a globally important exporter of other canned seafood products, including tinned shrimp. Here, Thailand has a 14.9% share of the world market, putting the country in third place among world suppliers, behind Vietnam and China, which have market shares of 29.0% and 19.5% respectively. Thailand is also a major exporter of canned sardines (second in the world with a 9.9% share after Morocco, which has a 40.6% share) and canned mackerel (again second in the world with a 10.1% share, this time after China with a 33.0% share). These last two products, canned sardines and canned mackerel, are also popular on the domestic market and as such, are sold on domestic and export markets in a ratio of approximately 2:3. Important players selling canned fish on the domestic market include Royal Foods (with the ‘Three Lady Cooks’ brand), Kuang Pai San (the ‘Smiling Fish’ brand) and Hi-Q Food Products (with ‘Rosa’ and ‘Hi-Q’ brands).

- Prepared and preserved seafood: Most of the output from this segment goes for export and originates with producers of chilled and frozen seafood and/or canned seafood that have expanded their operations to add value to their product line by manufacturing prepared and preserved shrimp or fish goods. Major players in this segment include Thai Union Frozen Products, KF Foods, Thai Union Seafood, Thai Royal Frozen Foods, and Seafresh Industry.

Situation

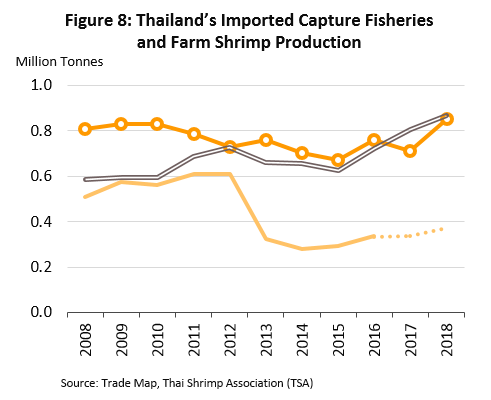

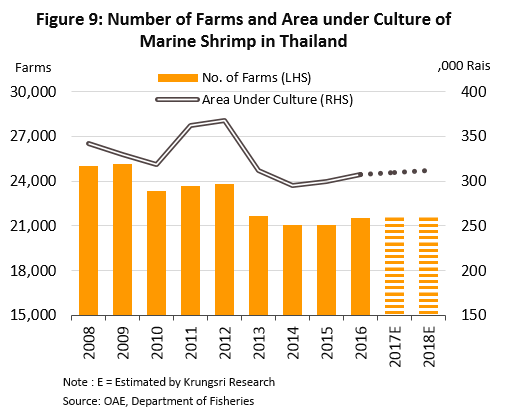

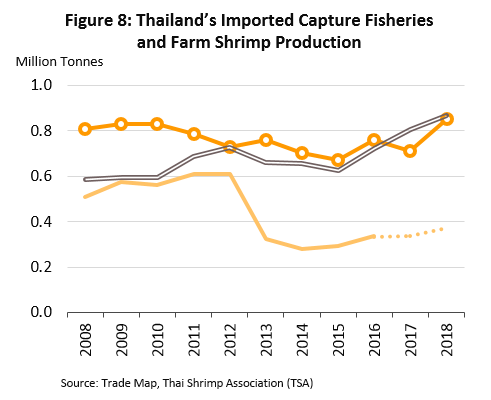

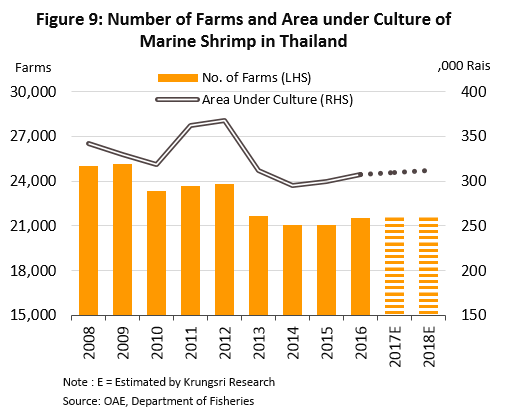

Between 2013 and 2017, the Thai processed seafood industry experienced depressed conditions as a result of: (i) a falloff in the quantity of inputs that were available, in particular of farmed shrimp (figures 8 and 9), which occurred as a result of the spread of EMS and which had the effect of lowering production of marine shrimp to an average of 0.25-0.3 million tonnes per year from the earlier pre-disease levels of 0.5-0.6 million tonnes; (ii) increasing competition on world markets, especially from competitors in Asia, including China, India, Indonesia and Vietnam; (iii) the increasing barriers to trade erected around markets in Europe and North America; and (iv) changing tastes that have increasingly favored fresh seafood (i.e. that has not been cooked, processed or flavored), especially among consumers in developed countries, Thailand’s main export markets. As a result of a combination of these factors, the value of exports of processed seafood from Thailand shrank by an average of -4.1% per year in these five years, compared to average growth of 5.3% in the preceding five years (2008-2012). In response to this strongly negative business environment, Thai operators rapidly adjusted their marketing strategies and attempted to expand domestic sales.

The current situation with regard to the market for exports of Thai processed seafood is given below.

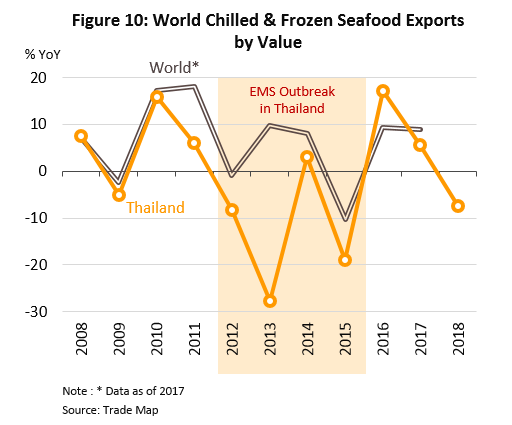

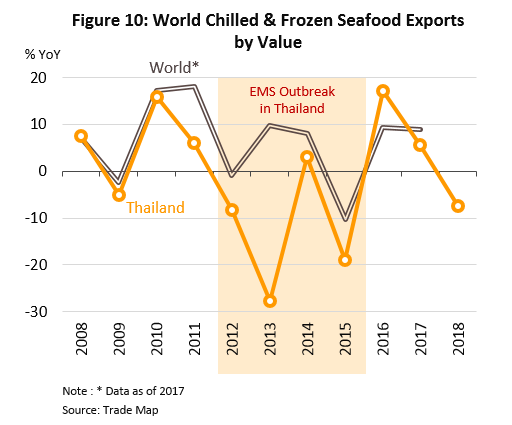

- Chilled and frozen seafood: Between 2013 and 2017, exports slid by an average of -2.6% per year as a consequence of: (i) the declining availability of seafood used as inputs by processors (figures 10 and 11); (ii) the decision by the EU to revoke Thailand’s eligibility for its Generalized Scheme of Preferences (GSP) for exports of seafood from January 1, 2015, thus causing import duties to rise (e.g. import duties on fresh shrimp rose from 4.2% to 12.0%, and those for squid increased from 2.5% to 6.0%); and (iii) the imposition of non-tariff barriers to trade (NTBs) by Thai trade partners, such as the 2014 move by the U.S.A. to reduce Thailand to a ‘Tier 3’ country in its Trafficking in Persons Report[7], and although Thailand was moved up to the ‘Tier 2 watch list’ in 2016, it remains in a less favorable position than do many of its competitors in Asia (e.g. India, Indonesia and Vietnam). In addition, in 2015, the EU gave Thailand a ‘yellow card’ for its fishing activities. This was in line with its IUU fishing regulations[8] and came as a result of Thailand’s illegal fishing, its lack of reporting and record keeping, and the absence of oversight within the industry. This then had an impact on the image of Thai products on world markets and as a result, the value of exports of chilled and frozen seafood fell at a rate that was steeper than the overall decline then seen on world markets. Details of the recent development of different product groups are given below (table 7).

- Chilled and frozen shrimps: Between 2013 and 2017, exports of chilled and frozen shrimp slipped by an annual average of -11%. This sharp decline in output was caused by the outbreak of EMS in 2011 and the fact that the problem took many years to overcome9/. As such, many shrimp farms, most of which were SMEs, had to cease operations under the weight of rising business costs, while operators were further affected by the need to reduce stocking ratios in farms in order to raise shrimp survival rates. This then reduced yields significantly and with this, exports of chilled and frozen shrimp likewise slumped, touching historical lows of 0.067 million tonnes in 2015, compared to 0.24 million tonnes in 2010 and although the problem began to abate from 2016, exports of shrimp remain only half of what they were before the outbreak of the disease. To make matters worse, Thailand’s competitors (e.g. India, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Ecuador) have also stepped up investment in facilities for raising and processing shrimp and because of this, Thailand’s share of global export markets crashed to 4.5% in 2017 from their 2012 level of 14.1%. For 2018, Thailand’s competitors further increased exports of shrimp, causing prices to slide and for Thailand, exports of chilled and frozen shrimp slipped by another -22.5% in terms of both value and quantity. Thailand’s main export markets for chilled and frozen shrimp are the U.S.A., with 30.5% of the value of all exports, Japan (20.4% of the market), China (13.7%), Vietnam (7.0%), Canada (5.4%), Taiwan (4.5%) and Malaysia (3.3%).

- Chilled and frozen fish and fish fillets: Between 2013 and 2017, by respectively volume and value, exports of these products declined by an average of -6.2% and -1.9% per year on a falling supply of fish. In 2018, a total of 0.13 million tonnes of chilled and frozen fish was exported (down -2.4% YoY), bringing in USD 172.7 m (-9.3% YoY). The main markets for Thai exports were Vietnam (19.1% of the value of all exports of Thai chilled and frozen fish), Malaysia (15.6%), Japan (12.7%) and Saudi Arabia (9.3%). The situation for fish fillets is starting to improve and in 2018, exports rose 9.8% YoY to 0.05 million tonnes, generating income of USD 258.0 m (up 3.5% YoY). The major markets for exports of Thai chilled and frozen fish fillets are Japan and the U.S.A., which occupy respectively 72.4% and 10.0% of the market, by value.

- Chilled and frozen cephalopods: The volume of exports of cephalopods slid by an average of -5.4% but at the same time, the value of these exports stayed relatively flat, with average annual growth of 0.3%. In 2018, exports dropped by a further -9.6% YoY to 0.042 million tonnes, which had a value of USD 330.6 m (down -4.3% YoY). The principal export markets for these goods are Japan (32.3% of the value of all exports of chilled and frozen cephalopods), Italy (25.8%), South Korea (17.9%) and the U.S.A. (6.6%). Although stocks of cephalopods have not seen the declines that wild-caught fish and shrimp have, competition has increased substantially in world markets, particularly from China thanks to its very large fishing fleet. This has then established China as the world’s leading exporter, with a 29.2% share, followed by Spain (9.0%) and Morocco (8.9%).

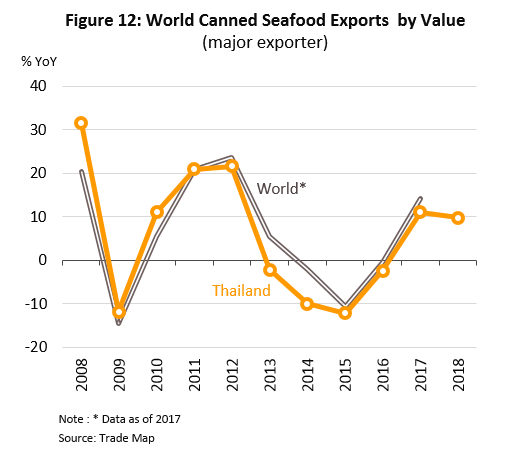

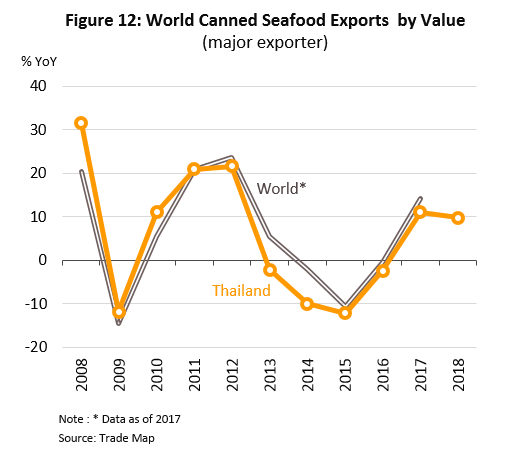

- Canned seafood: Movements in exports of canned seafood have been closely correlated to those of the world market (figure 12) due to declining fish supply and increasing barriers to trade.

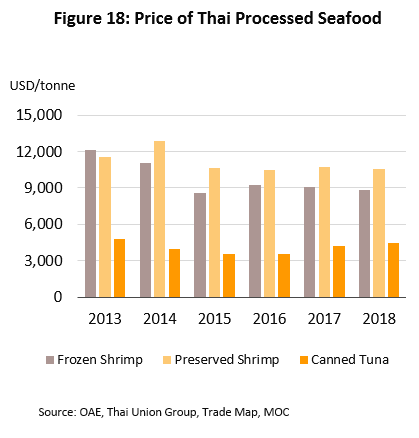

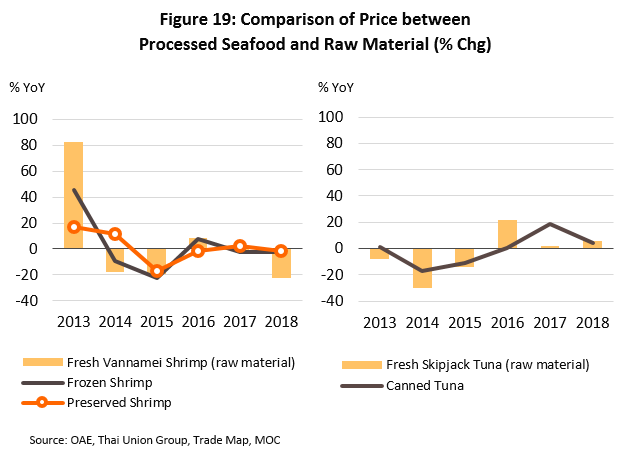

- Canned tuna: Growth in exports of Thai canned tuna has slowed substantially, with this being especially notable in 2017. This has been caused by: (i) the increasing competition in global markets; (ii) the rising cost of inputs, especially of tuna itself, which has now become somewhat expensive as a consequence of strict quotas on catch sizes; and (iii) the EU’s 2015 removal of Thailand’s ability to access their markets under the GSP scheme, which has increased input duties and as such, exports to the EU have declined. In 2018, by volume, exports of Thai canned tuna rose by 5.4% YoY to 0.51 million tonnes, though by value, the increase was at the substantially higher rate of 9.6% YoY (to USD 2.3 bn) due to the jump in the price of canned tuna (driven by the higher cost of imported inputs). The main markets for canned tuna exported from Thailand are the U.S.A. (21.1% of the value of exports of Thai canned tuna), Japan (9.2%), Australia (9.2%), the EU (5.7%) and Canada (6.4%).

- Canned sardines: As with other product groups, recent history has tended to be one of decline and between 2013 and 2017, exports of canned sardines shrank at an average annual rate of -17.3%, a rate that was significantly above average global declines of -5.1% per year. The rising cost of inputs has prompted operators to gradually cut production of canned sardines and instead switch to producing canned mackerel as a substitute product for distribution to the domestic market. Nevertheless, in 2018, demand for canned sardines from export markets, especially from South Africa and Japan, increased strongly on a growing preference for canned seafood and ready-to-eat products. This then lifted exports by 26.0% YoY to 0.06 million tonnes, which had a value of USD 143.1 m (up 32.1% YoY). Exports go mainly to South Africa (39.9% of the value of all exports of canned sardines from Thailand), Japan (11.0%), the EU (4.5%), Australia (4.3%), the U.S.A. (4.0%) and Panama (3.7%).

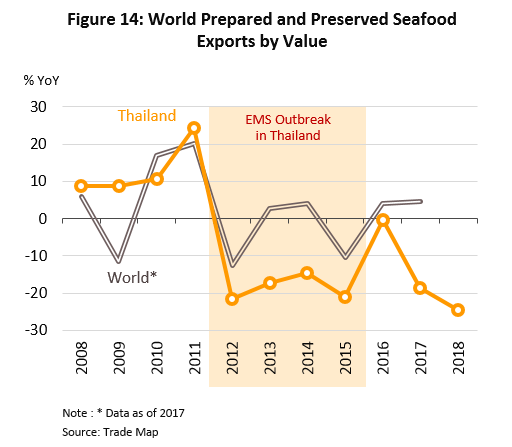

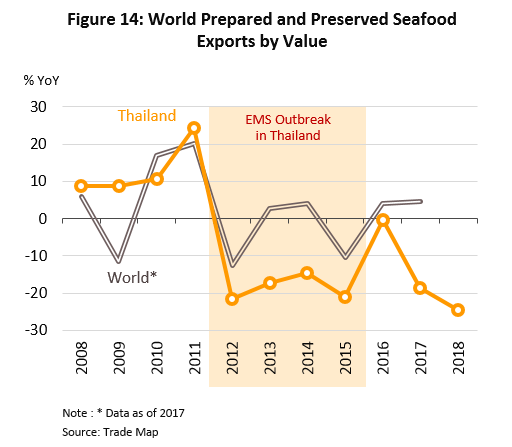

- Prepared and Preserved seafood products: Exports have contracted sharply, especially for processed shrimps (figure 14).

- Prepared and preserved shrimps: The impact of EMS on shrimp farms and the resulting crash in yields through the period 2013-2017 slashed exports of prepared and preserved shrimps by -10.4% per year. Exports continued to fall in 2018, by volume dropping to 0.05 million tonnes (down -18.4% YoY) and by value to USD 556.5 m (-19.8% YoY). At present, the main market is in the U.S.A. (42.5% of all exports in this segment) and Japan (35.9%).

- Prepared and preserved fish: Exports of prepared and preserved fish products averaged 0.15 million tonnes per year between 2013 and 2017. Large declines were recorded in the last of these years, 2017, this being caused by the rising cost of fish and of oil, the latter being a major contributor to overall costs for the fishing industry, and this prompted operators to cut imports of fish bought for further processing. However, in 2018, the situation improved somewhat and exports rose by 2.7% to 0.087 million tonnes, or in terms of value, to USD 325.1 m (up 0.2% YoY). The most important export markets are Japan (18.8% of total Thai exports of prepared and preserved fish products), the U.S.A. (12.9%), China (8.3%), Cambodia (7.4%) and Australia (7.3%).

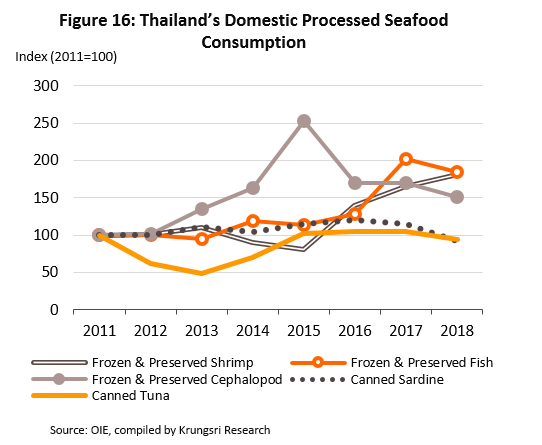

As regards the domestic market, demand for processed seafood products has increased steadily, with the market benefiting from the consumption patterns of urban Thais, who typically desire more convenient or more quickly prepared foods. In addition, the ceaseless expansion of modern trade outlets is also increasing the number of sales channels through which these products can be distributed, while to expand the domestic market and so help to compensate for losses in exports, new products are also being developed by manufacturers such as Charoen Pokphand, Prantalay Marketing, Surapon Foods, Thai Union, Lucky Union Foods, Royal Foods and Kuang Pei San Food Products). Details of these products are given below.

- Canned seafood: Improving spending power and changing lifestyles, which have increased demand for ready-made food, have fed into greater consumption of canned sardines and mackerel, while canned tuna (which has a 92% share of all canned fish products) has also benefited from higher purchases made by health-conscious consumers. In addition, manufacturers have been developing new products to meet rising consumer demand and because of this, between 2013 and 2017, consumption of canned seafood rose by an average of 6.6% per year in terms of volume and by 13.2% in terms of value. However, in 2018, growth in the domestic market for canned fish went into reverse and the volume of canned seafood distributed within the country shrank by -14.4% YoY to just 0.095 million tonnes, generating receipts of THB 10.551 bn (down -11.8% YoY). In part, this shift in the market was caused by consumers increasing their purchases of different types of convenience and semi-processed foods, which are sold through modern trade outlets in ever greater numbers.

- Chilled and frozen seafood: In the five years from 2013 to 2017, domestic demand for these products rose, especially for chilled and frozen shrimp products. These account for a full 52.5% of the market for chilled and frozen seafood, and are followed in importance by fish (38.5%) and cephalopod (9.0%) products. In this period, overall consumption of chilled and frozen seafood products increased rapidly, rising at an annual average rate of 17.5% by volume and 16.4% by value. In 2018, consumption totaled 61,501 tonnes (down -0.1% YoY) costing Thai consumers THB 13.90 bn (up 0.7% YoY).

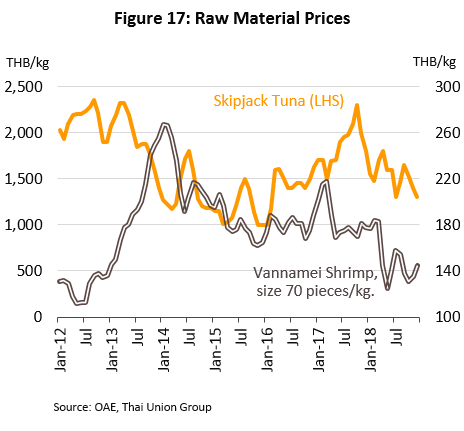

In the recent past, the Thai seafood processing industry has not only been affected by sluggish markets at home and abroad, but it has also been hit by the rising price of inputs and strengthening competition, which has severely restricted the room that Thai operators have to respond to these higher costs by increasing the price of their goods (figures 18 and 19). This has then had negative knock-on effects for the profitability of players within the sector.

Outlook

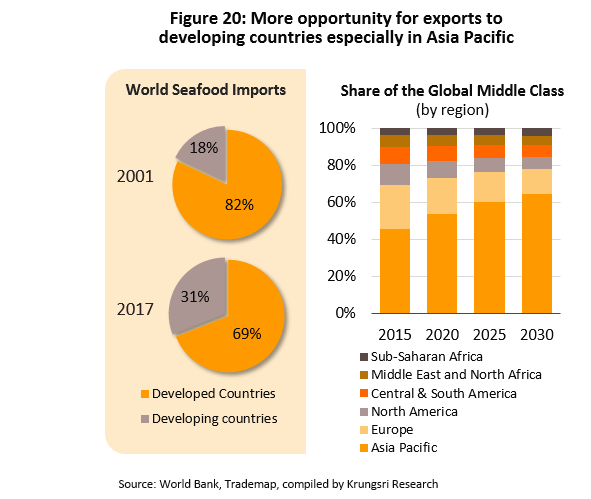

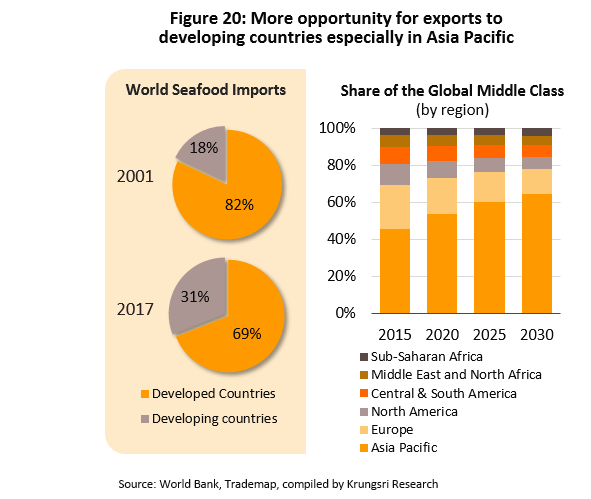

In the three years from 2019 to 2021, the Thai processed seafood sector is likely to see gradual growth, with a number of factors: (i) higher demand for seafood in both export and domestic markets due to growing urbanization and the middle classes, especially in developing or newly developed countries in the Asia-Pacific region (figure 20); and (ii) the improving image of Thai seafood products which helps to reduce obstacles to players’ attempts to expand their export markets. Thus, the latest issue of the State Department’s annual TIP report, released in June 2018, raised Thailand to a ‘Tier 2’ nation, the best ranking Thailand has ever had and one that is equal to many of Thailand’s Asian competitors (including India, Indonesia and Vietnam) and which is better than China’s, classified as a ‘Tier 3’ country. In addition, on January 8 2019, the EU rescinded the ‘yellow card’ that it had issued against Thailand for its infringements of EU IUU fishing regulations, a move that reflects the efforts made by the Thai government to reform the country’s legal framework and processes as they relate to fishing (table 8), as well as the adjustments to working practices made by Thai trawlers as they tried to meet the IUU fishing standards. (iii) Krungsri Research forecasts that the yield of farmed marine shrimps will also increase, and these better business conditions for shrimp farms will be helped by official policy to boost farmers’ abilities to raise shrimp, including by providing funds for diversifying the species of shrimps that are used and by helping with checks for infection. This should then lead to an increase in the supply of inputs for seafood processing plants.

However, at the same time, negative factors will also weigh on the market. (i) Wild fish stocks are tending to decline in size worldwide as the effects of climate change and uncertain climatic conditions begin to take their toll and this is then having an impact on supply chains. In addition, many countries are enforcing stricter laws regarding the entry of foreign trawlers into their territorial waters and are, for example, increasingly restricting permitted catch sizes and this is now having the effect of keeping prices for caught seafood at high levels and this in turn is pushing up prices for processed goods. (ii) Exports of seafood from Thailand continue to face a large number of obstacles, including consumers’ increasing desire to purchase fresh seafood (motivated by concerns over health), growth in intra-regional trade in Europe and North America, and Thailand’s continuing exclusion from GSP access to EU markets, which means that Thai exports are more expensive than those of their competitors. (iii) Competition on price is also increasing from Thailand’s competitors, in particular from China, India and Vietnam, countries that enjoy lower production costs relative to Thailand.

Krungsri Research forecasts that the value of Thai exports of processed seafood will rise by an average of 1-2% per year in the period 2019-2021, up from a 0.02% increase in 2018.

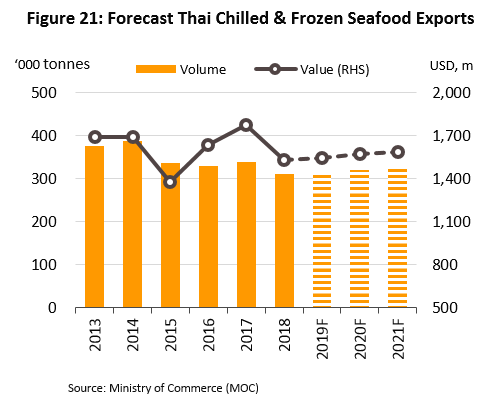

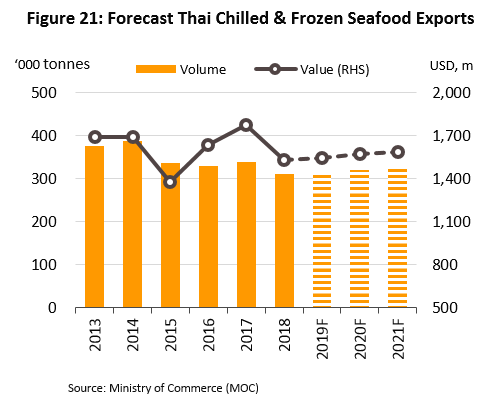

- Chilled and frozen seafood: Output by the chilled and frozen seafood sector is forecast to rise by 1-2% and 0.5-1% per year with regard to volume and value, respectively, which would compare favorably to the fall in output of -8.2 % and in value of -13.9% in 2018. This outlook is supported by an anticipated steady increase in demand on world exchanges, with this coming in particular from newly emerging markets in the Middle East, Africa and Latin America. In addition, the supply of marine shrimps (especially of farmed shrimp) to food processing plants will also tend to expand and since 50% of all exports of chilled and frozen seafood is of shrimp-based products, this will have an important impact on the sector. However, growth in exports from this segment will be limited because Thailand’s competitors (i.e. India, Indonesia, China and Vietnam) will tend to increase production for export, while major Thai players are also expected to increase their investments in overseas processing facilities as a route to overcoming problems with labor shortages (a situation that has in part been caused by the EU’s IUU fishing regulations and the US’s TIP report, which have together forced Thai officials to tighten their regulations and to increase checks on migrant workers employed throughout the seafood processing sector).

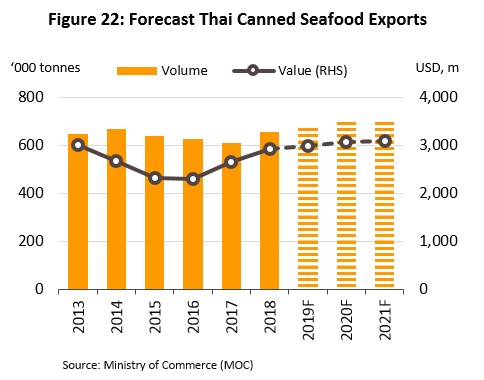

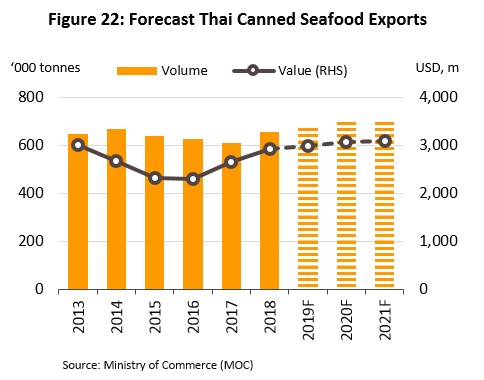

- Canned seafood: Exports of canned seafood are expected to rise by 1-3% annually in terms of volume and by 1-2% in terms of value, compared to figures for 2018 of 7.3% and 10.7%, respectively. Sales of canned tuna will be boosted by the dining preferences of middle class consumers in developing countries, the numbers of which are likely to continue to rise steadily and who generally prefer to purchase a greater proportion of ready-made foods. As for exports to developed nations, these are now facing limitations due to a shift among consumers to favoring fresh seafood products and Thai operators are therefore in the process of adjusting their production and marketing strategies from earlier models that emphasized exports of canned tuna, which in the past was a popular product in most western countries. Now, though, manufacturers are increasingly looking to develop seafood products that respond to the needs and tastes of consumers in developing countries.

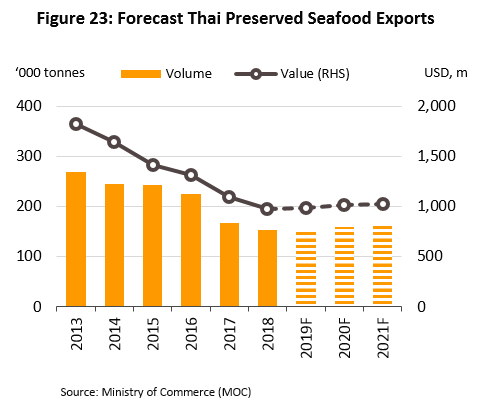

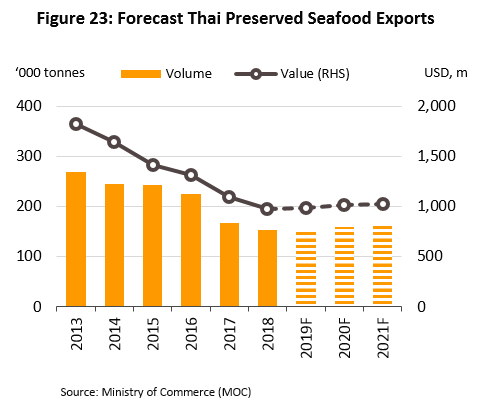

- Prepared and preserved seafood: The prepared and preserved seafood segment should grow by an average of 1-2% per year (for both volume and value). This follows steady declines in output that have been seen for some years and comes thanks to changing consumer lifestyles around the world that are helping to support rising demand for ready-made food. Sales from the segment will also benefit from companies revising their marketing strategies and, to increase added value and expand the range of marketing channels available, releasing a greater range of ready-made food products to the market.

The domestic market for processed seafood is expected to see similarly low levels of growth, and for the time period in question, it is estimated that this will run to 1-2% annually by volume and 0-1% annually by value (compared to falls of respectively -9.3% and -5.1% in 2018). Sales of frozen, prepared and preserved seafood will in particular see growth on changes in consumer lifestyle that support increased purchases of ready-made food and/or eating out, although these products will also benefit from growth in the restaurant and fast-food businesses, while manufacturers are also working to increase distribution through modern retail outlets, thus making it easier for them to connect to potential consumers of these products. The market for canned fish is likely to experience growth of only 2-3% per year with regard to both volume and value as expansion in sales is likely to be displaced by increased purchases of other types of ready-made or semi-prepared foods.

Krungsri Research view

The Thai seafood processing sector is expected to see growth in line with strengthening consumer demand over the next three years (2019-2021). However, operators’ profitability will come under pressure from a number of directions, including rising operating costs (labor, oil, and expenses arising from government-backed efforts to overcome problems such as those with the EU’s IUU regulations) and the persistently high costs of seafood used as an input for processing, while competition on world markets is also intensifying as competitors expand their production facilities. Supporting industries within the sectoral manufacturing supply chain will also tend to see a weakening of the market and the structural problems that affect this sector will take some time to overcome.

- Processors of frozen and processed seafood: It is expected that income for players in this segment will grow in step with any strengthening of the domestic and export markets but that profitability may soften on stiffening global competition and rising production costs.

- Producers of canned seafood: Rising demand in developing countries will help to boost income for manufacturers of canned seafood, especially for those making canned tuna since Thai producers of this are very proficient in marketing. Unfortunately, competition will also tend to intensify, as will the tendency of countries to erect barriers to trade and this may narrow the profitability of operators, especially those who produce canned products from sardines, mackerel, shrimp and shellfish, the majority of which are SMEs.

- Farmed seafood: Although the severe problems precipitated by the outbreak of EMS have now abated and the total domestic output of farmed shrimp is on the rebound, shrimp farms continue to be under pressure from high levels of competition and from increasing world output of shrimps, which makes it difficult for hard-pressed farmers to raise prices, or which even causes these to fall on occasion. Beyond this, operators also have to contend with high costs arising from, for example, the steadily rising price of feed and the additional costs of on-site systems that need to be installed to prevent the reoccurrence of disease.

- Fishing operations (excluding trawlers that catch seafood for further processing by the same company or within the same commercial group): Although demand for seafood for further processing is expected to rise, the majority of this is likely to come from imports. Most independent fishing operations are in the position of lacking a steady, pre-established market and so this puts them under a certain level of risk, while in addition, they now have to face rising costs (from more expensive oil), problems with labor shortages, and the additional expenses incurred by refitting boats with the extra equipment required to meet EU IUU fishing regulations; there is a risk therefore of some operations becoming insolvent.

- Chilled and frozen seafood storage facilities: Demand for facilities in which to store seafood is forecast to rise with demand for processed seafood products but competition in the provision of storage services is fierce as a result of the significant oversupply to the market. This situation has arisen because the major producers of processed seafood have invested in building their own storage capacity in order to be sure of meeting the standards set by officials in export markets, and as such, independent operators of chilled and frozen storage facilities are in a weak bargaining position relative to their customers, and their turnover is therefore expected to slide.

[1] Source: Office of Industrial Economics, Ministry of Commerce and an assessment by Krungsri Research.

[2] From industrial statistics supplied by the Office of Industrial Economics.

[3] Source: Office of Industrial Economics, Ministry of Commerce, and estimated by Krungsri Research.

[4] In 2017, Thailand was home to 251 shrimp hatcheries and nurseries, which had a total footprint of 674 rai. In the year, Thailand also had 8,248 shrimp farms that meet official standards, and these had a combined area of 140,000 rai (data from The Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives).

[5] Shrimp early mortality syndrome (EMS) is a bacterial infection that affects farmed shrimp. The disease destroys cells in the liver and pancreas of shrimps and typically affects shrimps in the first 20-30 days of release into farms. Mortality rates for farms typically run to 90-100% of their stock and it takes just 2 - 3 days for the disease to kill following its first appearance.

[6] These include skipjack tuna, yellowfin tuna, albacore or longfin tuna, bigeye tuna and bluefin tuna. These are deep-water fish and so cannot be found in Thai waters, but instead are caught in the Atlantic, Indian and Pacific oceans.

[7] The Trafficking in Persons Report, or the TIP Report, is an annual publication issued by the US State Department that reports on the situation with human trafficking in countries around the world. Countries are classified into one of four levels. (i) Tier 1 countries are those that meet accepted standards; (ii) Tier 2 countries are those that are attempting to meet accepted standards; (iii) countries move to the tier 2 watch list when they are attempting to meet accepted standards but there are also many victims of human trafficking in that country, or the number of victims is increasing rapidly, or the government is unable to present evidence that it is trying to solve problems with human trafficking; and (iv) Tier 3 countries are those that do not meet accepted standards and that make no significant effort to solve problems with human trafficking within their borders.

[8] The EU’s ‘Illegal, Unregulated and Unreported‘ (IUU) fishing regulations divide countries into three groups, according to the fishing practices: (i) countries for which there is no reported illegal fishing or unreported activating and where fishing is duly regulated; (ii) countries that receive a ‘yellow card’ and that need to change their regulations to bring them into line with those of the EU; and (iii) countries that receive a ‘red card’ and that therefore have access to EU markets for their seafood products blocked.

[9] Stopping the spread of shrimp early mortality syndrome took some time because farm pools had to be taken out of service in order to remove the biological waste that collects at the bottom. They then had to be dried, and new management systems for the pools had to be put in place, including for example installing systems for filtering and cleaning water, and eradicating infections and disease vectors in the pools through the use of chlorine or iodine. These changes also emphasized the importance of checking on the health of hatchlings and reducing stocking density, all of which increased costs for shrimp farms.

.webp.aspx)