EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Krungsri Research sees the Thai sugar industry contracting through 2024. Although the domestic market receives the positive impacts of recovery in the tourism sector and an improving outlook for the restaurant business, the contracted exports due to the effects of drought on agricultural outputs offset those positive impacts. However, the situation will improve over 2025 and 2026 thanks to the emergence of La Niña conditions and thus of a more favorable climate; the high price of sugar and the incentive effects of this on supply growth; and an uptick in economic activity and ongoing growth in the tourism sector that will then underpin rising demand from downstream industrial consumers at home and abroad, most obviously those in the food and beverage industries. Nevertheless, players will still have to overcome several headwinds, including the elevated costs faced by sugarcane growers, the ratcheting up of Thailand’s sugar tax and the introduction of similar measures in many export markets, rising global concerns over the health impacts of sugar consumption, and uncertainty over the domestic regulatory environment, especially the potential impacts on profits of amendments to the Sugarcane and Sugar Act.

Krungsri Research view

Over 2024-2026, income will rise in line with overall sales, but the Thai industry’s heavy reliance on export markets will expose players to an elevated level of volatility and uncertainty.

-

Sugar mills: Income will rise on strengthening consumption, which will itself be lifted by: (i) economic growth and the improving purchasing power at home and abroad; (ii) growth in downstream industries (most notably for food and drinks manufacturers) as the COVID-19 pandemic fades; (iii) continuing worries about infection that will sustain demand for disinfecting alcohol; (iv) an acceleration in economic activities that will create an uptick in demand for transport services and heavier demand for ethanol; and (v) government measures that stipulate an increase in gasohol’s ethanol content. Additionally, the industry also benefits from its strong and secure supply chains, its ability to develop a wide variety of products, and ongoing investment in high-value downstream industries that involve the commercial exploitation of waste and byproducts arising from the sugar milling process. However, although these factors will help to sustain profits, competition for access to sugarcane will bid up prices, and as these rise above the benchmark, some processors may face cashflow problems and turn to loss.

-

Traders: Traders selling into export markets are expected to benefit from stronger sales to downstream industrial consumers and from growth in the tourism and restaurant industries. However, they may also be exposed to greater risk arising from the effects on prices of supply alterations and of fluctuations in the prices set on global exchanges, which would then force players to absorb higher stock management costs.

-

Sugarcane growers: Improved climatic conditions should raise outputs and boost the sugar content of Thai-grown sugarcane, but farmers may have to contend with greater price volatility as changes in global exchanges feed through into domestic markets. In addition, farmers are in a weak bargaining position relative to sugar mills, while compared to 2-3 years ago, production costs are rising on more expensive energy, fertilizer, pesticides, herbicides, and labor, especially during the harvest of fresh sugarcane. This will then impact net profits and may negatively affect future planting decisions.

Overview

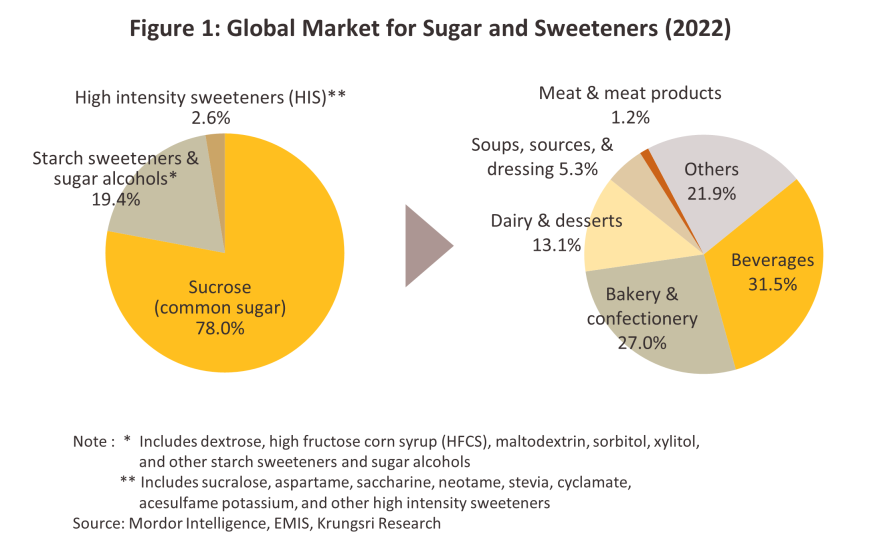

Sugar is a plant-derived product that is used to increase sweetness1/. Global demand for sugar remains strong, with sugar consumed both directly and indirectly, in the latter case as an additive or flavoring in a wide range of other products, including foods, beverages, processed dairy products (milk, butter, yoghurt, etc.), candy, baked goods and so on. In 2022, 78.0% of all sweeteners consumed globally2/ were sucrose-based, with the remainder being accounted for by a number of non-nutritive products. These include natural items such as honey, stevia and monkfruit (also called luohan guo), high intensity sweeteners such as aspartame cyclamate and neotame, and starch sweeteners and sugar alcohols (e.g., maltrodextrin, fructo-oligosaccharides and inulin) (Figure 1).

Products derived from sugar processing can be split into the following.

-

Raw sugar: This brown substance, though the color can range from light to dark, has moderate moisture and high molasses content, exhibits a tightly packed crystalline structure, and tends to contain large quantities of impurities and residues. Raw sugar is subject to further process, and this then results in white sugar, refined sugar and other sugar-derived products including ethanol, alcohol, and bioplastics. This refining process is what converts raw sugar into a product fit for human consumption.

-

White sugar: This is obtained by removing impurities from raw sugar. White sugar is crystalline, colored white to pale yellow, has a low molasses and moisture content, and is loosely aggregated and more friable than raw sugar. White sugar is an ingredient for domestic household use and is also used as a raw material in food and drinks processing.

-

Refined sugar: This goes through the same refining process as white sugar but the end product has fewer impurities and tends to be in the form of clear white granules. Refined sugar is very pure, with zero molasses content and very low or zero moisture. Refined sugar is generally produced for household consumption and for industrial processes that require very pure sugars, such as making carbonated and energy drinks, and producing pharmaceuticals.

-

Byproducts of sugar refining: Byproducts or value-added products that arise from sugar refining include molasses3/, bagasse4/, filter cake5/, vinasse6/ and steam7/.

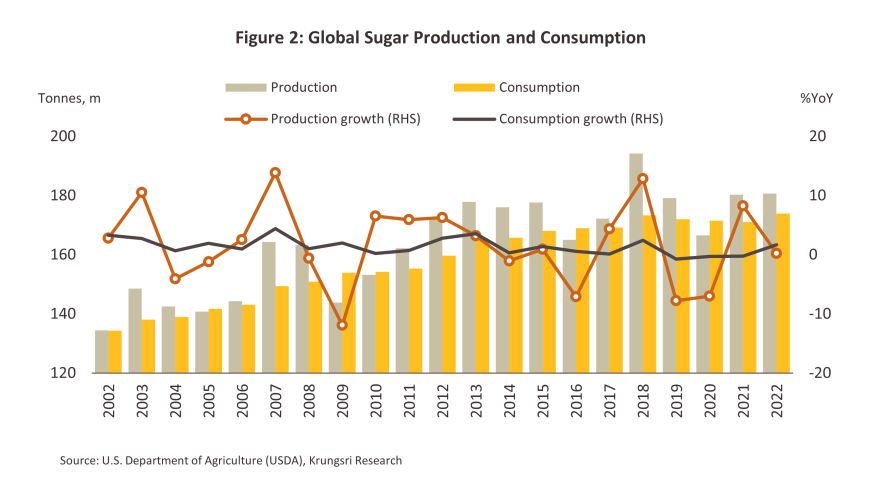

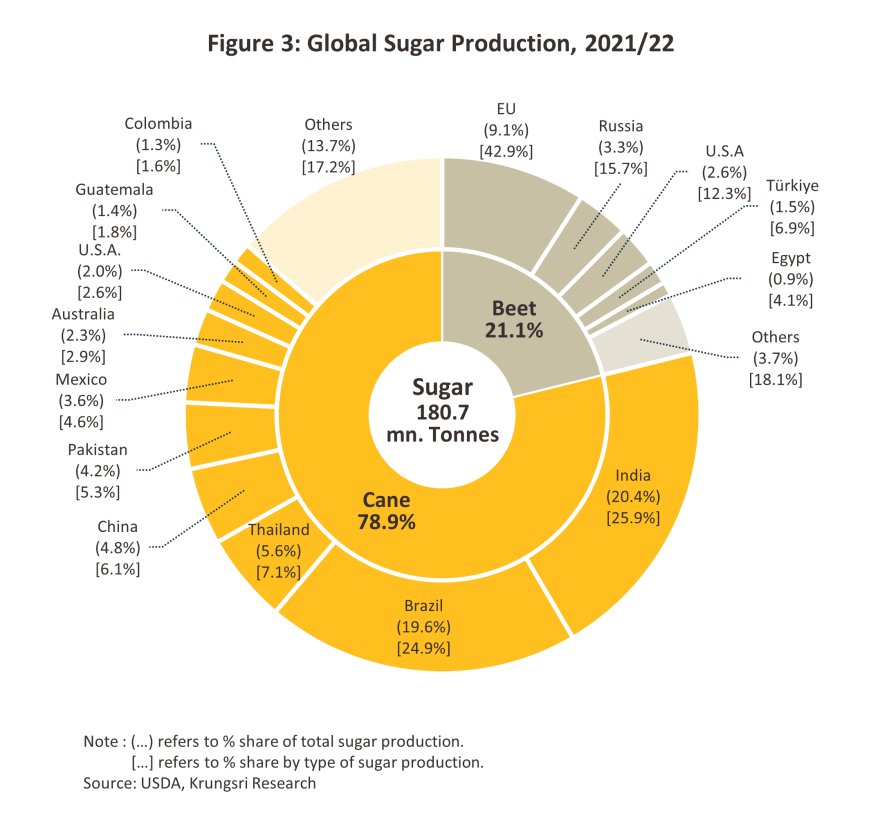

Over the two decades between 2002 and 2022, global output and consumption of sugar climbed steadily (Figure 2). This was due to a combination of the increase in the world population from 6.3 billion in 2002 to 8.0 billion in 2022 and growing demand for sugar from industrial consumers, especially in the production of ethanol and for use by food and drink manufacturers. In 2022, global sugar production thus hit 180.7 million tonnes (measured as raw sugar), with the biggest producers being India (20.4% of global production), Brazil (19.6%), the European Union (9.2%), Thailand (5.6%), China (5.3%), and the US (4.6%). Production can also be categorized according to the source of the sugar. (i) 78.9% of global output came from sugarcane, most of which was grown in countries in equatorial zones and in the Asia-Pacific region, including India (the source of 25.9% of all sugarcane-produced sugar), Brazil (24.9%), Thailand (7.1%), China (6.1%), and Pakistan (5.3%). (ii) The remaining 21.1% of the world’s supply of sugar came from sugar beet, 42.9% of which originated in the European Union. The EU was followed in importance by Russia (15.7%), the United States (12.3%), Türkiye (6.9%) and Egypt (4.1%) (Figure 3).

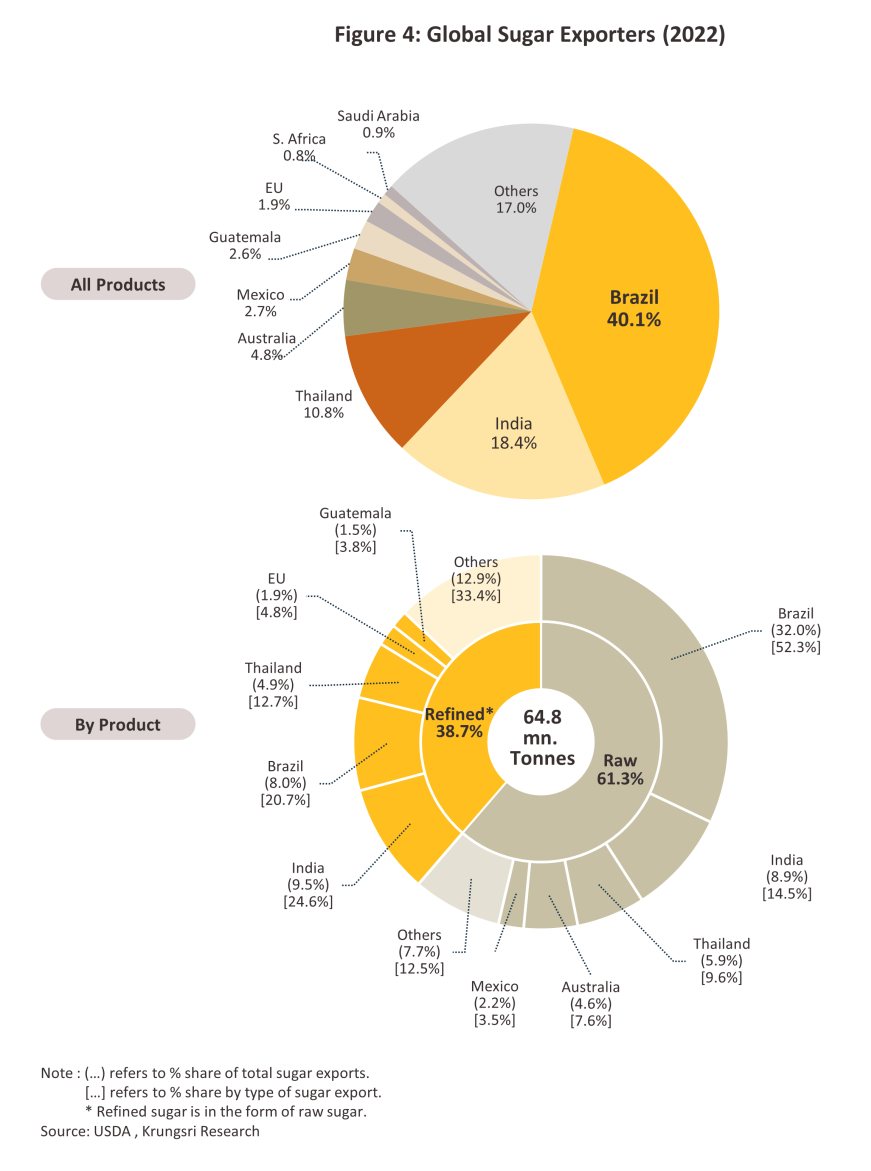

In 2022, a total of 64.8 million tonnes of sugar was traded on world markets, this thus representing 35.9% of global production. The largest exporter was Brazil, which was the source of 40.1% of supply to global markets, followed by India (18.4%) and Thailand (10.8%) (Figure 4). By product type, exports are split between: (i) raw sugar (61.3% of all exports globally), for which Brazil is the main originator (52.3% of all exports of raw sugar) and then in order of importance, India (14.5%), Thailand (9.6%), and Australia (7.6%); and (ii) refined sugar (38.7% of exports), for which the main exporters are India (24.6% of exports of refined sugar), Brazil (20.7%), Thailand (12.7%), and the European Union (4.8%) (Figure 4).

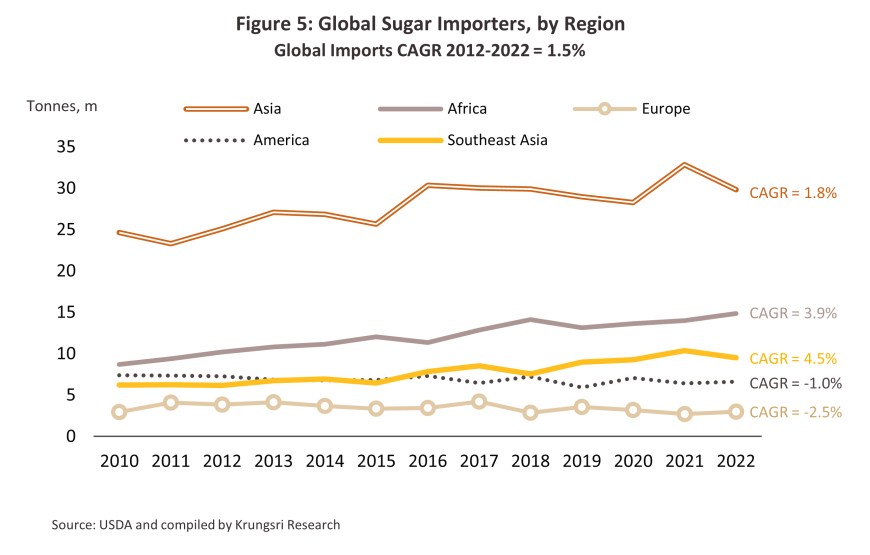

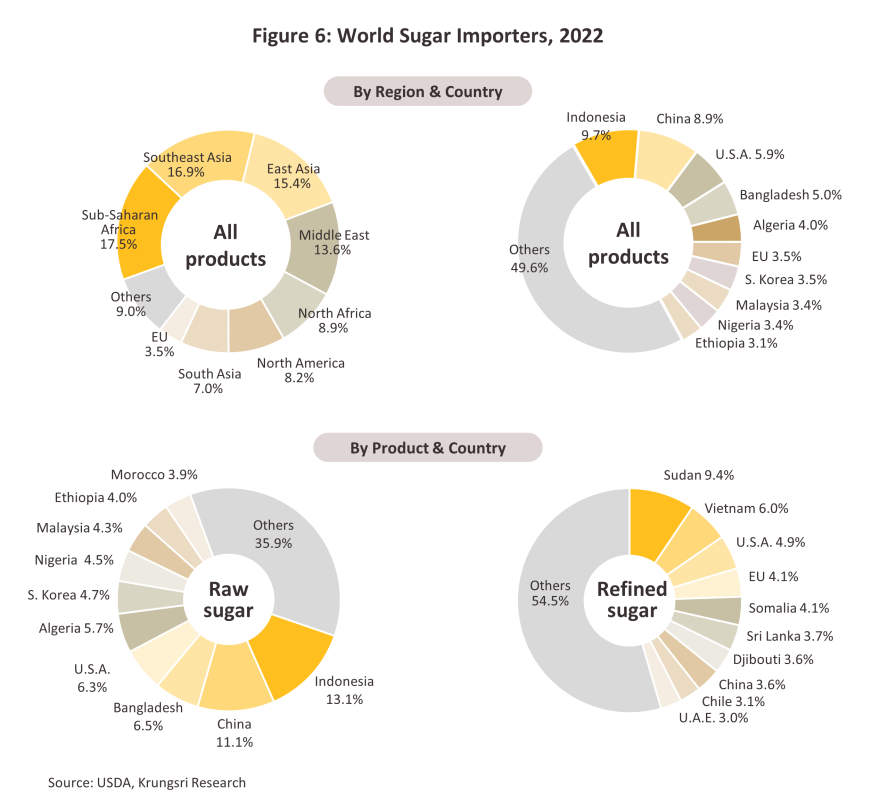

The world’s most important importers of sugar are in Asia, and with a 9.7% share by quantity, Indonesia is currently the world’s leading buyer of sugar traded on global exchanges (Figure 5 and Figure 6). Coming after Indonesia in order of importance are China (8.9%), the United States (5.9%), Bangladesh (5.0%) and Algeria (4.0%). Considered by type, Indonesia is the world’s largest importer of raw sugar (13.1% of the world import quantity), followed by China (11.1%), Bangladesh (6.5%), the United States (6.3%), and Algeria (5.7%), while for refined sugar, the biggest importers are Sudan (9.4% of all global sales of refined sugar), Vietnam (6.0%), the United States (4.9%), the European Union (4.1%), and Somalia (4.1%).

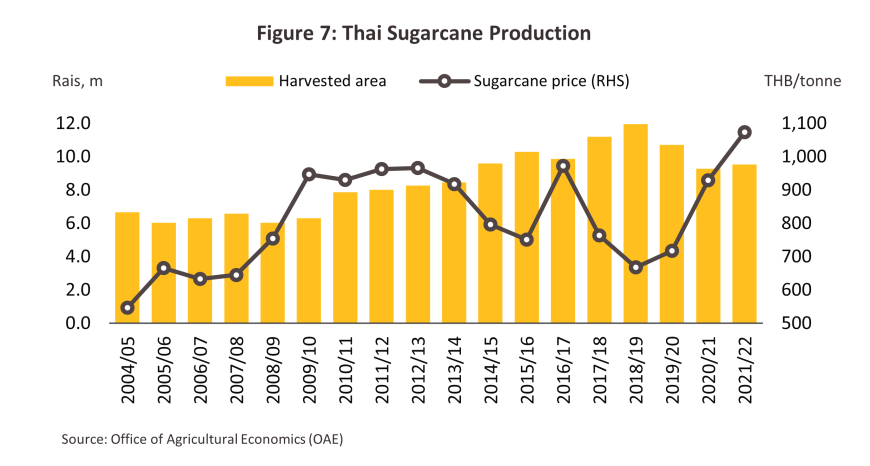

Thailand-based cultivation of sugarcane has expanded rapidly in recent years, increasing by roughly half between 2010 and 2022; at the start of the period, 6.3 million rai was under cultivation, but by 2022 this had increased to 9.5 million rai, thus giving an average rate of increase of 3.5% annually (Figure 7). This rapid expansion in supply was spurred by a combination of attractive prices and steadily rising domestic and international demand that originated from both consumer and industrial end-users, in the latter case most notably the food and drinks industries and dairy processors.

.

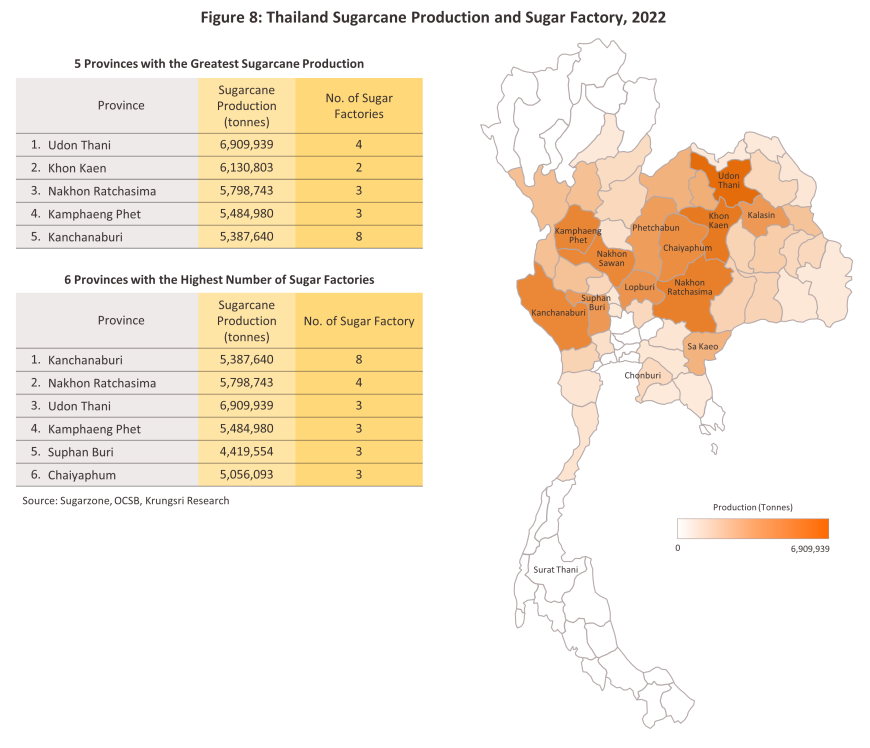

Within Thailand, cultivation of sugarcane is concentrated in the Northeast (44.9% of all sugarcane harvested areas), followed by the North (27.3%), the West (13.7%), the Central Region (9.4%) and the East (4.7%). Individually, the most important sugarcane-growing provinces are Kamphaeng Phet (7.1% of all Thai farmland used for the cultivation of sugarcane), Nakhon Sawan (7.0%), Udon Thani (6.8%), Kanchanaburi (6.3%), Khon Kaen (6.0%), Lopburi (5.7%), and Nakhon Ratchasima (5.6%) (Figure 8).

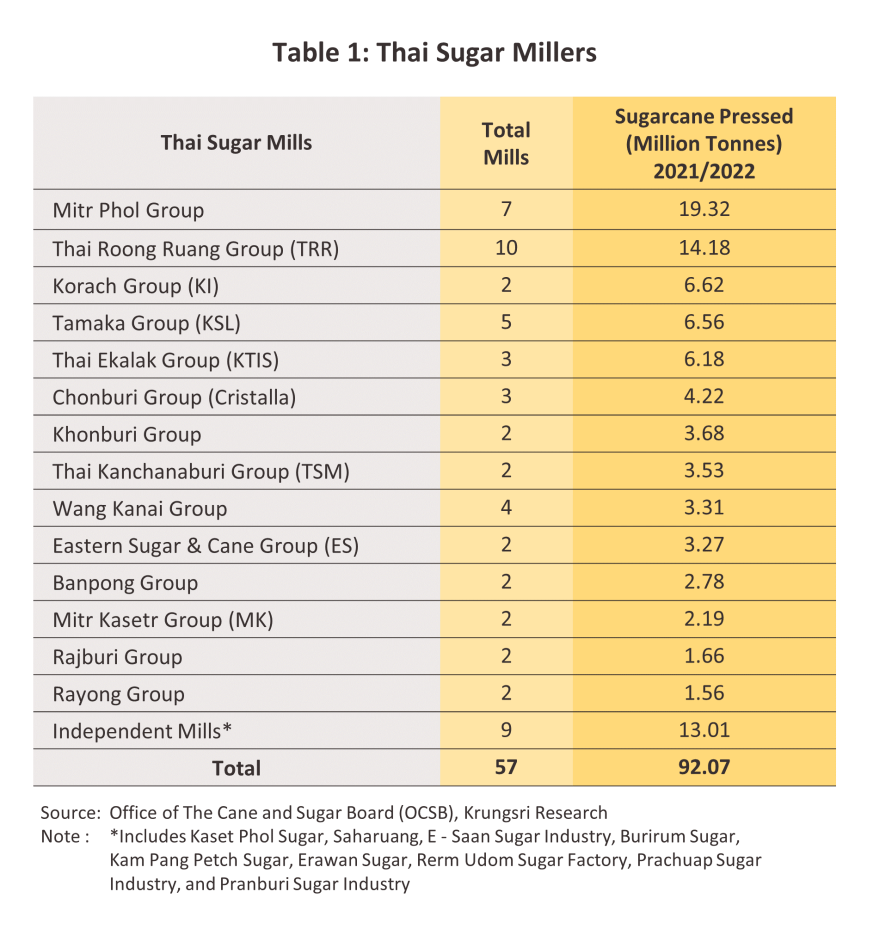

At present, there are 57 sugar mills operating in Thailand8/ (Table 1), the majority of which are located close to sugarcane growing areas since this: (i) facilitates the sourcing of inputs according to production plans; (ii) cuts transportation costs; and (iii) makes it easier to communicate with growers, or to offer them help and assistance. In addition, considerations related to logistics often have an influence on the location of mills, so these will often be sited close to urban areas, ports, and centers of trade. Thus, the greatest concentration of sugar mills is in Kanchanaburi, which is home to 8 sites, followed by Nakhon Ratchasima (4 mills), and Udon Thani, Kamphaeng Phet, Suphanburi and Chaiyaphum, with 3 each

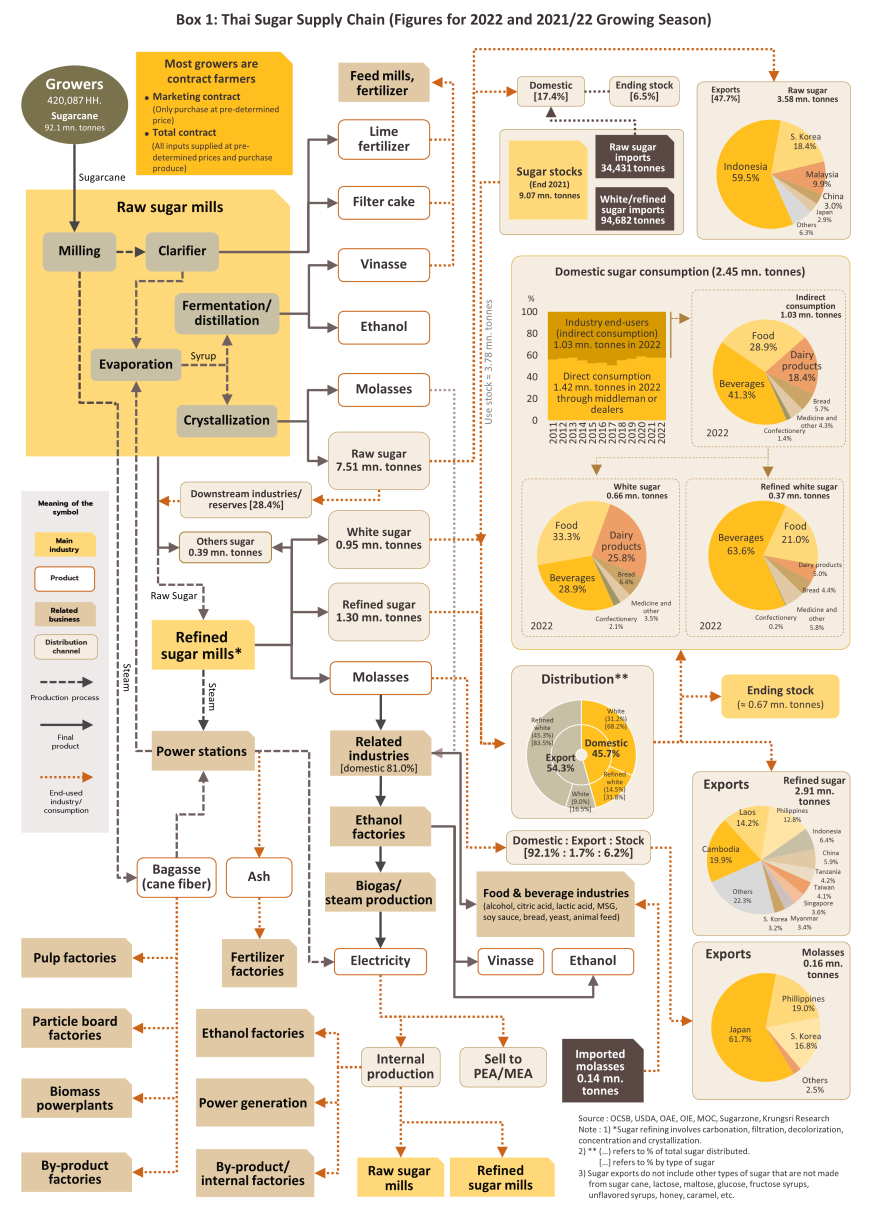

With 70% of output sold overseas, the Thai sugar industry relies primarily on export markets, of which the most important are Indonesia (buyers of 34.8% of all Thai sugar exports volume), South Korea (11.7%), Cambodia (8.8%), Lao PDR (7.0%) and the Philippines (6.1%). The state of export markets for the main product groups in 2022 is outlined below.

-

Raw sugar: Exports of raw sugar comprised 53.8% of all Thai sugar exports in 2022, or a total of 3.6 million tonnes. The main markets for this were in Indonesia (buyers of 59.5% of Thai exports volume of raw sugar), South Korea (18.4%), Malaysia (9.9%), China (3.0%) and Japan (2.9%).

-

White sugar: 2.9 million tonnes of white sugar were exported in 2022 (43.8% of Thai sugar exports volume), for which the biggest markets were Cambodia (19.9%), Lao PDR (14.2%), and the Philippines (12.8%).

-

Molasses: Molasses exports amounted to 2.4% of all Thai sugar exports in 2022, or 0.2 million tonnes. This was bought principally by the three countries of Japan (61.7% of Thai molasses exports volume), the Philippines (19.0%), and South Korea (16.8%).

Domestic consumption absorbed 30% of the industry’s output9/, split between 57.8% that was sold to the consumer market for household consumption and 42.2% that went to industrial buyers for use in beverage production (41.3% of industrial consumption volume), food processing (28.9%), processing with milk products (18.4%), and other uses (11.4%).

In addition to receipts from the sale and distribution of sugar, companies also generate income from the commercial exploitation of byproducts arising from the sugar refining process. These include molasses, which is used to produce ethanol and indeed thanks to government promotion of this (mainly by specifying the proportion of ethanol that is mixed with gasoline to sell as gasohol)10/ demand is growing. Many sugar mills have also invested in downstream businesses that use byproducts of sugar milling as inputs, including biomass energy production11/ and the manufacturing and production of paper pulp, particle board, and fertilizer (Box 1).

Situation

The situation for the global sugar industry is described below.

-

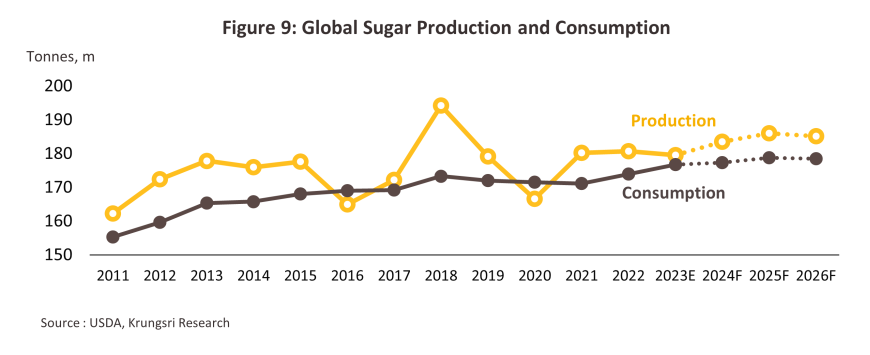

In 2023, global supply inched down -0.6% to 179.5 million tonnes (Figure 9) on the back of the drought-induced -6.3% decline in beet output. European production was thus badly hit, and sugar production on the continent dropped -15.5%. Drought also depressed sugarcane-based production in many key sugar-producing nations, including China (-9.4%), Pakistan (-9.3%) and Mexico (-15.5%). However, the situation was mixed and for many other big producers, output actually increased. Beneficiaries of this included Brazil (+7.3%), where a more favorable rainfall and climate helped to lift outputs, while the dip in the cost of crude helped to push ethanol prices below those of sugar, encouraging a switch in production from the former to the latter. Likewise, production rose in both India (+0.3%) and Thailand (+8.9%) thanks to better weather and increased access to water, and overall, this helped to offset global production losses elsewhere.

-

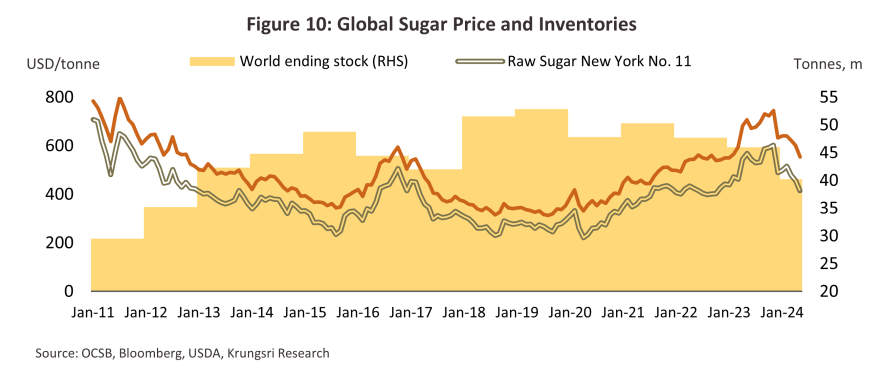

Global demand for sugar rises 1.6% to 176.8 million tonnes (Figure 9). Demand was helped by the relaxation of COVID-19 restrictions and the resulting reopening of countries and rebound in economic activity. However, this was counterbalanced by a number of headwinds, including the emergence of El Niño conditions and worries that this would undercut supply and leave this unable to fully meet domestic demand. Some countries, most importantly India12/, thus restricted or blocked exports of sugar for that supply was sufficient to ensure domestic food and energy security. In addition, ongoing economic sluggishness dragged on consumer spending power, and the result of this was that some importers cut back on their purchases. Given this, global sugar exports contracted -4.1% to 62.2 million tonnes, but with demand moving in the opposite direction, world stocks shrunk -3.6% to 46.0 million tonnes (Figure 10) and global prices rose to a 13-year high. Thus, in November 2023, prices for raw sugar New York No. 11 and white sugar London No. 5 hit highs of respectively USD 602.1/tonne and USD 745.2/tonne, which was sufficient to lift average prices across 2023 to USD 530.3/tonne (+27.8%) and USD 664.8/tonne (+23.5%) (Figure 10).

The situation for the domestic sugar industry through 2023 is summarized below.

-

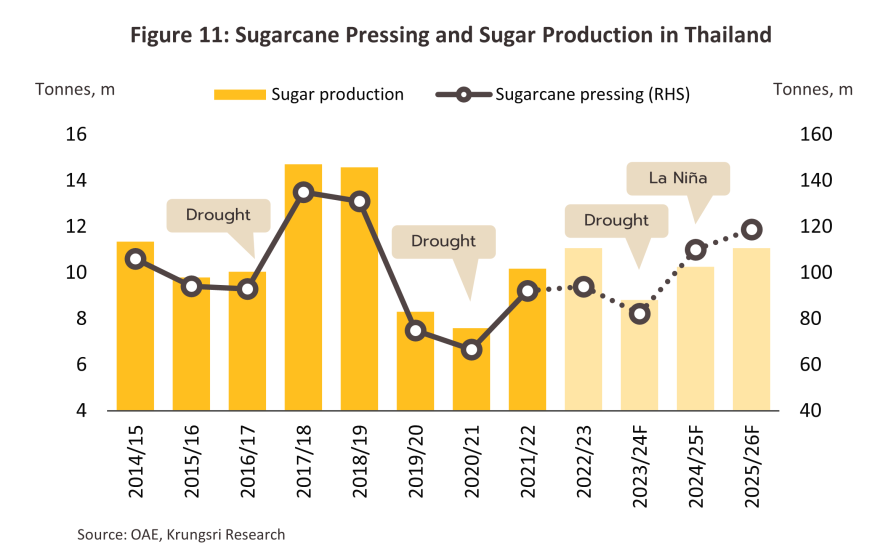

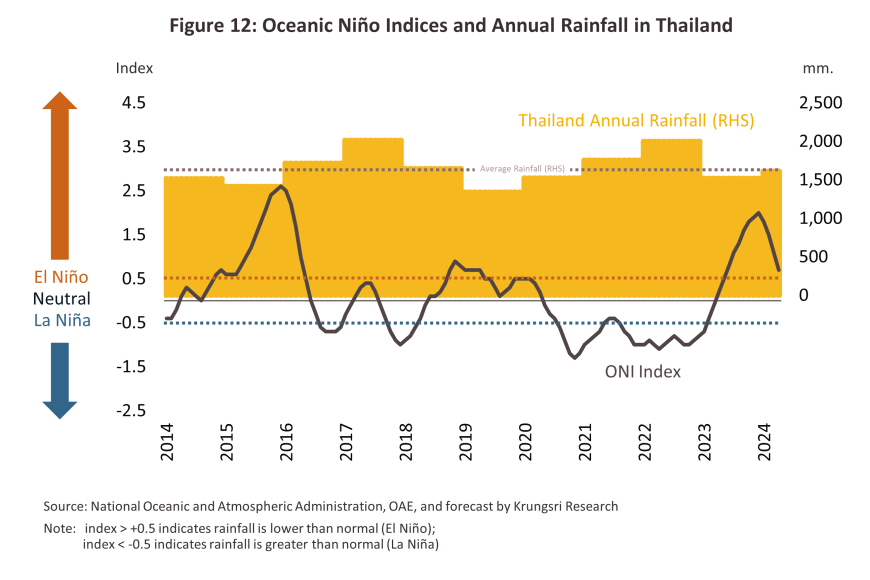

The volume of sugarcane being pressed in the 2022/2023 growing season increased 2.0% to 93.9 million tonnes, though the quantity of sugar produced from this jumped 8.9% YoY to 11.1 million tonnes (Figure 11). An improvement in business conditions was driven by: (i) above average rainfall through the 2022 planting (Figure 12) that lifted yields and pushed the average sugar content to 13.3 CCS13/, up from the previous year’s 12.7 CCS; and (ii) an expansion in the area under cultivation, itself a result of positive price signals coming from the increase in the minimum price paid by mills and the rise in prices on global sugar markets (caused by worries over worldwide sugarcane outputs and sugar stocks). Domestic sugarcane prices thus surged 27.8% to an average of THB 1,165.8/tonne, up from the 2019 low of THB 668.2/tonne and above average production costs of THB 1,122/tonne14/.

-

-

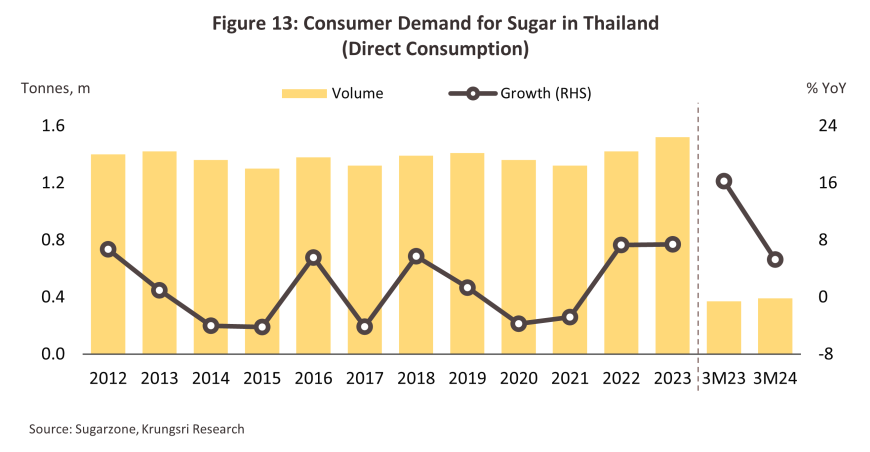

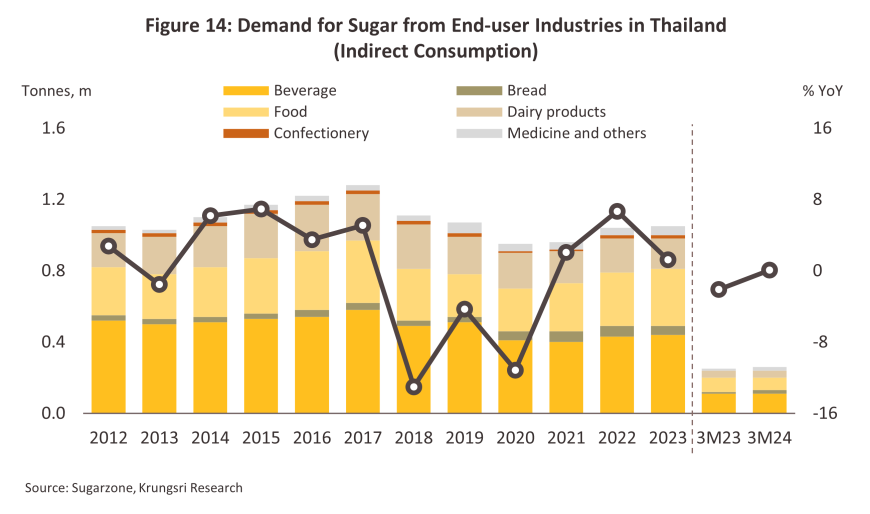

Combined domestic consumption of white and refined sugar rose 4.8% to 2.57 million tonnes in 2023. Demand was lifted by the ending of COVID-19 restrictions and the reopening of the country, which then kickstarted the economic recovery and the rebound in the tourism sector. Growth in direct consumption, in particular in restaurants, benefited from strengthening spending power, while indirect consumption by downstream industries also rose by 1.2%, split between increases in purchases of 1.9% by the beverage industry, 5.7% by food processors, 16.2% by manufacturers of medicines and pharmaceutical products, and 2.8% by sweet/candy manufacturers (these industries account for 78% of combined indirect demand for sugar) (Figure 13 and Figure 14). However, growth has been restrained by the enforcement of phases 2 and 3 of the Sugar Tax15/, which has particularly affected growth in demand from producers of carbonated and sweetened drinks. Over the first 3 months of 2024, consumption of white and refined sugar expanded by another 3.1% YoY to 0.66 million tonnes thanks to increases in direct demand of 5.3% YoY (to 0.39 million tonnes) and of 0.1% YoY (to 0.27 million tonnes) in sales to downstream industrial consumers. These improvements were driven by strengthening economic conditions, especially in the tourism, restaurant, and drinks industries. Demand also rose from some downstream industries, including baking (this encompasses the brewing of beer and the distillation of spirits) (+46.7% YoY), dairy products (+11.7% YoY) and medicines and pharmaceuticals (+38.5% YoY) but this was balanced by declines of -12.6% YoY and -4.0% YoY in purchases by food processors and beverage producers.

-

Exports of Thai sugar and molasses edged up 0.7% to 6.7 million tonnes on growth in the main markets of Indonesia (+0.1%), the Philippines (+66.4%), Malaysia (+31.9%) and Taiwan (+25.6%). Sales were lifted by both demand- and supply-side factors. In the case of the former, global demand is expanding by some 1.0-2.0% annually, driven in particular by use in the food and beverage, ethanol, and alcohol industries, while on the supply side of the market, India (one of Thailand’s major competitors) moved to restrict exports of sugar on worries over the tightness of domestic supply, thus opening a space into which Thai players could move. As a result, export prices for sugar and molasses jumped 11.5%, lifting export earnings by 9.8% to USD 3.5 billion (Figure 15 and Figure 16). However, growth went into reverse over 5M24, falling -43.6% YoY to a 3-year low of 2.2 million tonnes. Export earnings were also down -34.3% YoY to USD 1.3 billion. This turnaround in the market was driven by a -58.3% YoY slump in exports to Indonesia (Thailand’s most important market), as well as falls of -54.0% YoY to South Korea, -79.4% YoY to the Philippines, and -52.9% YoY to Malaysia. These worsening business conditions were a result of a combination of economic weakness in export markets and the impacts of the drought on Thai supply, which then helped to push up the export price of sugar and molasses by another 16.5% YoY.

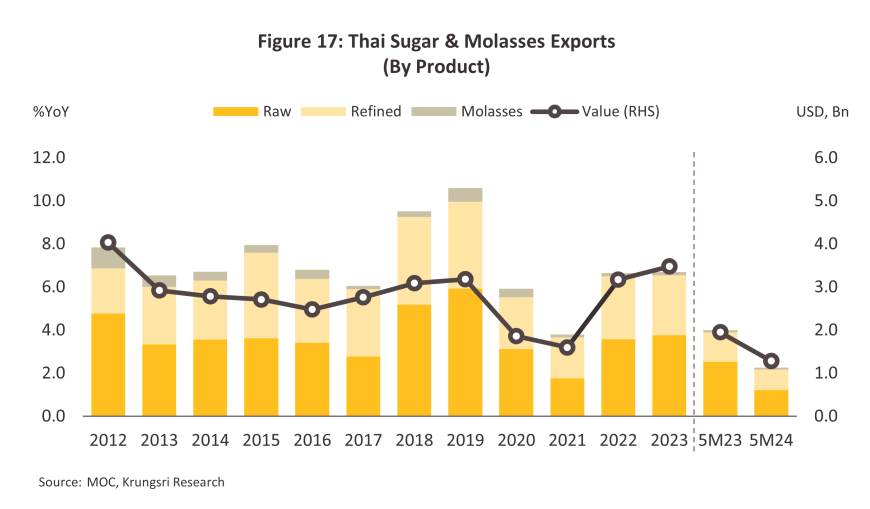

Details of export volume and earnings by product category (Figure 17) are given below.

-

Raw sugar: In 2023, exports rose 5.1% to a total of 3.8 million tonnes, which then brought in receipts worth USD 1.8 billion (+11.2%). Growth was supported by an improving outlook for regional export markets, an area where Thailand benefits from its membership of the ASEAN Free Trade Area. With the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic fading, sales were boosted by strengthening direct consumption and an increase in demand from downstream industrial users and as a result, exports rose 4.6% to Indonesia (to 2.2 million tonnes), 34.3% to Malaysia (to 0.5 million tonnes), and 118.7% to Vietnam (to 0.1 million tonnes). Export prices were also up 5.5% to an average of USD 484.3/tonne over the year, but through 5M24, the situation reversed and as a result of worsening economic conditions in many countries, export volume and value slumped to respectively 1.2 million tonnes (-52.2% YoY) and USD 0.6 billion (-45.1% YoY). Declines of export volume were seen across all Thailand’s main markets, including Indonesia (-58.3% YoY), South Korea (-62.3% YoY), Malaysia (-68.5% YoY), and Taiwan (-81.7% YoY). However, export prices rose 14.7% YoY to USD 527.0/tonne.

-

White sugar: By volume, exports slipped -4.5% to 2.8 million tonnes, but by value, these rose 8.7% to USD 1.7 billion. Sales volume declined in most export markets in the year, including to the CLMV nations (-7.6% to 1.1 million tonnes), China (-22.5% to 133.0 kilotonnes), Indonesia (-51.5% to 90.1 kilotonnes), Tanzania (-60.1% to 48.7 kilotonnes), and Kenya (-53.9% to 41.3 kilotonnes). Sales were disrupted by the onset of El Niño conditions and the resulting supply shortages, which then prevented Thai exporters from fully meeting demand in overseas markets, though one consequence of this was to lift white sugar export prices by 15.7% to USD 619.4/tonne. Exports continued to slide through 5M24, falling another -29.5% YoY to 1.0 million tonnes, though export value declined at the slightly slower rate of -18.5% to reach USD 0.6 billion. This worsening outlook was repeated across Thailand’s principal export volumes of the Philippines (-91.3% YoY), Indonesia (-59.7% YoY), Singapore (-29.9% YoY), and Taiwan (-16.4% YoY). However, markets closer to home generally performed better, including Cambodia (+20.6% YoY), Lao PDR (+29.3% YoY), and Myanmar (+10.4% YoY). At the same time, export prices climbed by another 15.6% YoY to USD 656.3/tonne.

-

Molasses: Exports fell to 0.15 million tonnes (-2.7%), sales of which brought in receipts worth USD 24.5 million (-7.3%). With an approximately 60% market share, Japan is Thailand’s largest export market, but the Japanese economy’s only sluggish performance through 2023 undercut demand for molasses from the ethanol, biomass, and animal feed industries and so imports from Thailand fell back -4.8% to 92.9 kilotonnes. Export prices also dipped -0.7% to USD 178.8/tonne. Exports continued to soften over 5M24, declining by value by -7.3% YoY to USD 13.5 million and by volume by another -17.8% YoY to 82.4 kilotonnes. These declines are explained by the -19.9% YoY drop in export volume to the Philippines and the -14.8% YoY fall in sales to Japan, the two markets accounting for more than 99% of Thai overseas sales of molasses. 5M24 export prices climbed 12.8% YoY to USD 163.4/tonne.

Outlook

-

The USDA expects that across 2024, global sugar output will expand by 2.2% to 183.5 million tonnes. Favorable local rains and the rise in the price of sugar above that of ethanol will encourage Brazilian producers to step up production, and as a result, this should expand by 19.7% to 45.5 million tonnes. However, drought in Asia will mean that across the year, sugar production in India, Thailand, and Pakistan will likely dip. In 2025 and 2026, Krungsri Research sees worldwide production growing by just 0.5-1.5% CAGR. Although Brazilian output will grow in 2024, the forecast return of drought conditions to the country will likely undercut outputs, with consequences for world markets. Nevertheless, supply will benefit from: (i) the onset of La Niña conditions in much of Asia, and the more favorable weather will help major producing nations expand outputs; (ii) the rise in prices above the trend shown in recent years, which will incentivize farmers to expand the total area under cultivation; and (iii) the need to build stocks to ensure that supply is sufficient to meet growing demand from consumers and industrial users.

-

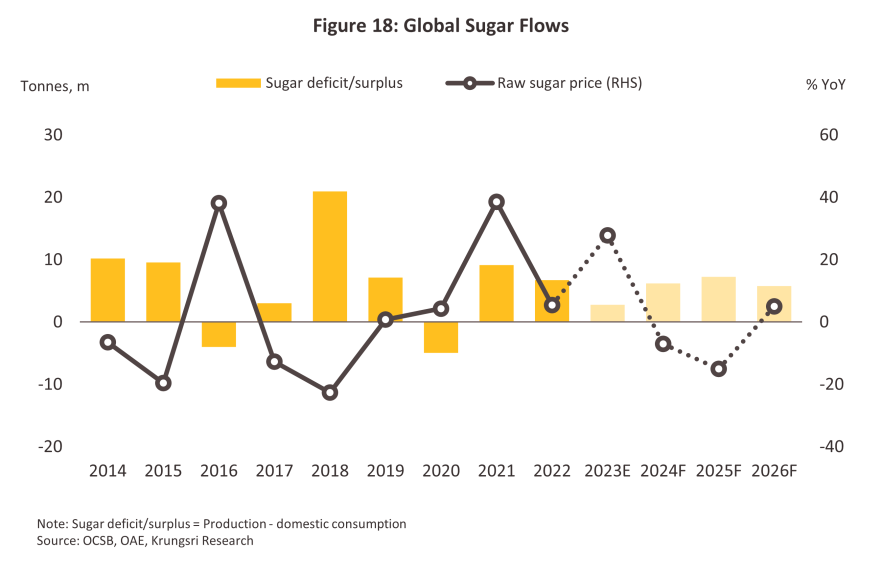

Over 2024-2026, global demand for sugar is also forecast to expand at an average rate of 0.5-1.5% annually on recovery in the tourism industry, the subsequent demand from the food and beverage industry, and the general increase in global economic activity. However, growth in supply is expected to outpace that of demand (Figure 18) and this will tend to keep global prices for raw sugar at USD 440-460/tonne (20.0-20.9 ¢/lb) over 2024 to 2026, down from 2023’s average of USD 530.3/tonne (24.1 ¢/lb).

An expected improvement in the economic outlook for Thailand and its trading partners should lift the domestic sugar industry over the next three years. Details of this are given below.

-

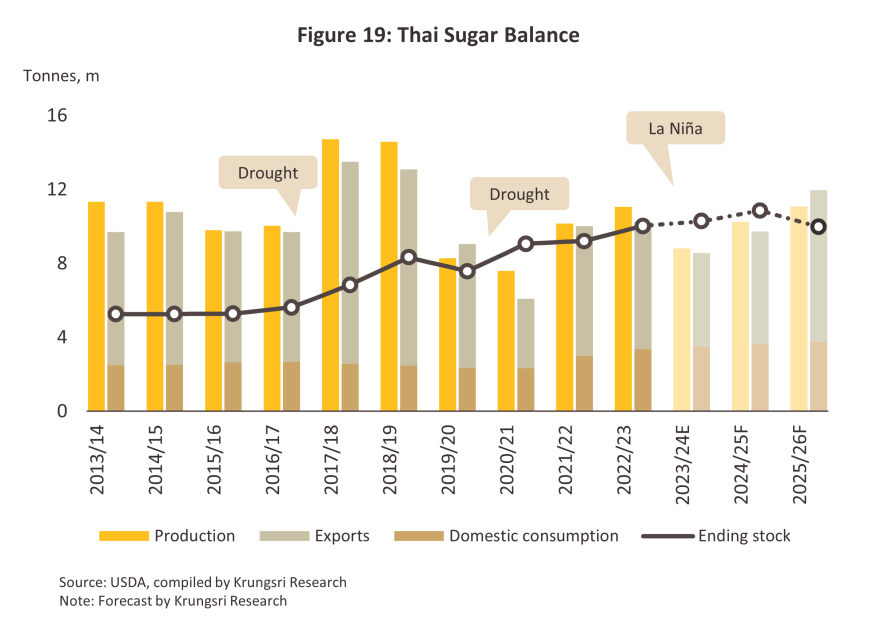

The volume of sugarcane being pressed is forecast to contract -12.5% to 82.2 million tonnes in 2024, and this will then produce some 8.8 million tonnes of sugar (Figure 19). Supply is being hurt by: (i) unusually high temperatures resulting from El Niño that have caused crop losses and reductions to outputs; (ii) the switch by some farmers to growing cassava in place of sugarcane thanks to the former’s attractive sale price, greater drought tolerance, and ease of harvest; (iii) high production costs, especially for fertilizer and energy, that are then encouraging farmers to neglect care of their crops, further reducing yields; and (iv) problems with labor shortages and high wages, especially during the harvest of fresh sugarcane. Nevertheless, moving forward, the situation should improve. In the 2025 and 2026 growing seasons, outputs are forecast to jump to 114-116 million tonnes of sugarcane, sufficient to produce 10.6-10.8 million tonnes of sugar annually (up 11.0-13.0% pa). This turnaround will be helped by: (i) the transition from El Niño to La Niña conditions16/ resulting in an increase in rainfall, which will benefit sugarcane growers since much of this is planted beyond the reach of irrigation systems; and (ii) the incentive effects on growers of earlier higher prices. However, because supply from major producers (Brazil, India, and Thailand) is expected to broaden, prices at both the global and national levels will come under pressure. Domestic prices for sugarcane are thus predicted to fall by between -5.0% and -7.0% annually to THB 950-1,050/tonne.

-

Over the next 3 years, domestic sugar consumption should grow by 3.0-4.0% annually to 3.5-3.8 million tonnes yearly (Figure 19). This positive outlook is supported by: (i) the rebound in the tourism sector and ongoing expansion in the economy, which will boost direct demand for sugar from the food and beverage industry; (ii) stronger demand from downstream industrial consumers, especially from manufacturers of food and beverages; (iii) post-COVID changes in consumer behavior that are encouraging individuals to continue to use disinfecting alcohol (produced from molasses); and (iv) government support for the industry, in particular by setting the required ethanol content in gasohol, and greater demand for ethanol17/ from the transport industry, which will be lifted by ongoing economic expansion, an acceleration in spending on infrastructure projects, and increased uptake of travel services by tourists. This will, though, be partly balanced by the levying of the sugar tax on sweetened drinks, which will then drag on growth in demand.

-

Exports are expected to fall to just 4.8-5.1 million tonnes in 2024, slumping by between -25% and -30% on the impacts of the El Niño on the supply of sugarcane. In addition, the ongoing rebound in the tourism sector is stoking demand from the food and drinks industry, and so players are looking to reserve stocks to meet this. Nevertheless, the situation should improve, and exports are forecast to swing back to annual growth of 15.0-20.0% in 2025 and 2026, sufficient to push total overseas sales of sugar and molasses to 6.7-7.5 million tonnes per year. The business environment will benefit from: (i) better weather condition, which will support an expansion in the area under cultivation and a rise in outputs, thus alleviating earlier supply shortages and allowing companies to better fill export orders; (ii) ongoing growth in export markets that will add to demand from downstream industries in these countries; (iii) the move by India (a major competitor of Thailand) to promote ethanol production from sugarcane which, coupled with problems ensuring that the supply of sugar is sufficient to meet domestic demand, may result in the country introducing export controls; and (iv) progress on agreeing new FTAs18/ that will then open up new export markets. Less positively, Thailand is likely to face greater competition within its current export markets as Brazil responds to strengthening demand by diverting inputs from the manufacture of ethanol back to sugar production.

Despite the broadly positive outlook described above, players in the Thai sugar industry will face several challenges in the coming period. (i) Production costs may exceed the price realized by selling sugarcane. Persistent problems with labor shortages mean that harvesting costs may be prohibitive. (ii) Domestic supply has come under pressure as growers switch to planting crops that are easier to harvest, are more drought- and pest-resistant, and that realize higher prices, and this has left sugar mills with excess capacity. (iii) Growth in sugar consumption is being undercut by rising global consumer concerns over personal health and wellness, while the introduction of sugar taxes in Thailand and in export markets is reducing demand from drinks manufacturers. (iv) Uncertainty over the outlook for the regulatory environment is rising. (a) Current regulations stipulate that no more than 0-5% of burnt sugarcane accepted for pressing by mills, but in the 2023/2024 season, 29.6% of burnt sugarcane coming in for pressing19/. Additional measures, both financial and legal, will thus be needed to address this problem. (b) The Sugar and Sugarcane Act is currently being revised (the 2nd amendment, B.E. 2565 or 2022), and as part of this, farmers have proposed that bagasse be redefined as a byproduct resulting from the manufacturing process. However, this would have an impact on the profit-sharing scheme20/ and on mills’ income since this would then oblige these to share receipts from the sale of bagasse with farmers, rather than keeping this for themselves as happens at present. These issues are currently under consideration and a decision has yet to be reached21/.

Changes to the industry in the coming period

-

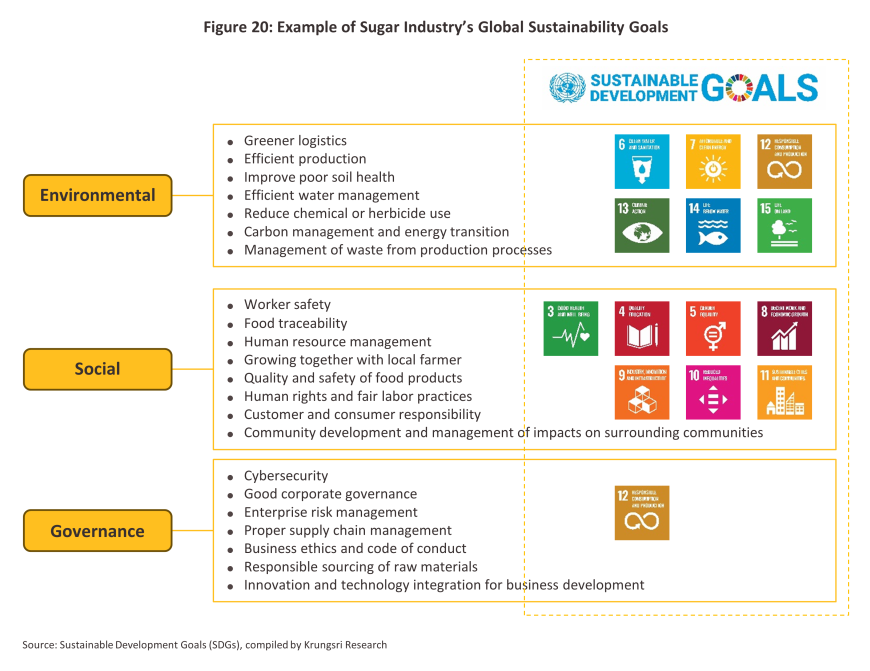

The industry will focus on ensuring security of supply. This will involve: growers cooperating to make the SDG goals22/ a reality, in particular those relating to water resources and the environment; managing costs to better generate economies of scale; supporting greater technology transfer from sugar mills and government agencies; and expanding the reach of irrigation systems, thus cutting the risk of future supply shortfalls. In addition, the BCG model23/ will be used to support the development of the industry and its supply chains, thereby raising farmers’ profits and ensuring that inputs are secured for the sugar industry as a whole.

-

Growing interest in environmental issues and in the ESG (environmental, social and governance) issues is influencing the strategic decision-making processes of both government agencies and private-sector players. These are thus pivoting towards a greater focus on reducing pollution, particularly air pollution, by the sugar and sugarcane industry, and to this end, a wide range of policies are being considered. These include the greening of the industry and the transition to carbon neutrality, which will itself be facilitated by the use of smart farming technology and innovation that extends across the production lifespan, from initial planting to the transport of harvested products to mills. On-farm processes will therefore be increasingly automated, the sale of sugarcane leaves for alternative uses will help to reduce the incentives to burn crops prior to harvest, training in better harvesting techniques will help farmers maintain higher CCS levels in their crops, and improvements to policy will encourage purchases of fresh sugarcane and better challenge ongoing problems with burnt sugarcane.

1/ Sugars are found in low quantities in most plant tissues but sugarcane and beet have sufficiently high concentrations that they can be cultivated for the commercial production of sugar.

2/ Considering only sugar.

3/ Molasses is produced from boiling down sugarcane or beet during the sugar refining process. This results in a viscous, dark brown liquid that is used as an input into ethanol production (which is then mixed into gasohol) or in the food and drinks industry to make products including alcohol, yeast, monosodium glutamate, pet food, vinegar, and a range of different sauces.

4/ Although bagasse is a waste product resulting from the pressing of sugarcane, it is one of the main inputs into biomass energy production. Bagasse is also used to produce packaging and various construction materials including fiber board, particle board, melamine faced chipboard, medium-density fiber board (MDF), synchronous MDF, lacquer high gloss MDF, and pure cellulose.

5/ As its name suggests, filter cake is produced from the filtering of liquid sugarcane extracts. The residue left behind by the filtering processing contains nutrients and minerals that can be used to make fertilizer or animal feed, or processed into biogas.

6/ Vinasse is used to make organic fertilizer and animal feed.

7/ Surplus steam can be used to power machinery or to generate electricity for use within the sugar mill.

8/ As per an announcement in the Royal Thai Government Gazette on August 17, 2015, the earlier requirement that sugar mills be sited at least 80 kilometers away from one another was reduced to a distance of 50 kilometers.

9/ This does not include imports of raw sugar that are used to make white sugar or stocks of raw sugar held in the country.

10/ In 2023, installed production capacity for the manufacture of ethanol from sugarcane and molasses came to 3.43 million liters per day (this does not include another 1.05 million liters per day of capacity in facilities that use both cassava chip and molasses). This then generated annual demand that totalled over 3.3 million tonnes for molasses (-3.8%) and 1.0 million tonnes for pressed sugarcane (+12.5%).

11/ Energy produced from bagasse-powered biomass facilities is generally consumed within the sugar mill itself or sold to nearby consumers.

12/ Through 2023, India struggled against excessive heat, disruption to the monsoon rains, and stiff inflation in food prices.

13/ CCS is an abbreviation of ‘Commercial Cane Sugar’. This is a system used to determine the quality of sugarcane, and in particular, the quantity of refined sugar contained in the cane that will be released by pressing. A higher CCS thus indicates a greater sugar content, with a CCS of 10 showing that by weight, the cane is 10% realisable sugar. 1 tonne (or 1,000 kg) of 10 CCS sugarcane will therefore yield 100 kgs of refined sugar

14/ From data supplied by the Office of the Cane and Sugar Board and the Office of Agricultural Economics.

15/ Taxes are levied on drinks with a sugar content greater than 6 grams per 100 milliliters. At present (April 1st, 2023 to March 31st, 2025), the sugar tax is at phase 3 of its implementation, with the tax set at five rates: (i) A sweetness level of 0-6 grams per 100 milliliters is tax exempt; (ii) a sweetness level of 6-8 grams per 100 milliliters incurs a duty of THB 0.3/liter; (iii) a sweetness level of 8-10 grams per 100 milliliters incurs a duty of THB 1.0/liter; (iv) a sweetness level of 10-14 grams per 100 milliliters incurs a duty of THB 3/liter; and (v) a sweetness level of 14-18 grams per 100 milliliters incurs a duty of THB 5/liter. In the future, the rates of tax within these bands will be stepped up, with phase 4 running from April 1st, 2025 onwards. This tax has had the effect of prompting manufacturers to cut the quantity of sugar in their drinks.

16/ The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) predicts that there is a greater than 50% chance that over July-September 2024, the Pacific will switch to La Niña conditions (i.e., rainfall is likely to be above average) (source: Weekly ENSO Evolution, Status, and Prediction Presentation, NOAA, 10 June 2024).

17/ Krungsri Research sees demand for ethanol expanding by 2.0-2.5% annually over 2024-2026 to reach a total of some 3.0-3.8 million liters/day. Demand will be boosted by: (i) predicted annual economic growth of 2.5-3.5%; (ii) a 2.5-3.5% annual increase in the number of vehicles on the road that run on gasohol; (iii) ongoing growth in e-commerce; and (iv) plans by the government to make E20 the standard gasohol mix.

18/ The Department of Trade Negotiations is currently in discussion over free trade agreements (FTAs) with Pakistan, Türkiye, Sri Lanka, and the EFTA (the European Free Trade Area, which includes Iceland, Lichtenstein, Norway, and Switzerland), as well as participating in the negotiations over the ASEAN-Canada agreement. The Department also has plans for a future FTA with the EU. Many of the countries involved in these agreements are major importers of sugar.

19/ The Office of the Cane and Sugar Board has requested budget allocations to help fund assistance for sugarcane growers trying to meet government targets for cuts in PM2.5 pollution. This assistance takes two forms: (i) help ‘in cash’, or payments to farmers for not burning their crops; and (ii) help ‘in kind’, or assistance accessing the technology needed to better manage growing and harvesting. These policies will be implemented through 5 measures: (i) loans to help farmers address environmental problems; (ii) access to improved agricultural machinery; (iii) legal measures; (iv) cuts to payments for burnt or untrimmed sugarcane; and (v) better allocation of sugarcane and sugar production to mills, thus helping to solve problems with illegal pressing of burnt sugarcane and the generation of PM2.5 pollution.

20/ A revenue-sharing system (the ‘70:30 system’) has been established by law to split revenue between sugarcane growers and sugar millers. In each growing season, the system divides net profits from distribution to domestic and export markets between farmers, who receive 70% of net profits as ‘compensation for the sugarcane price’, and processors, who receive 30% as ‘compensation for production’. These proportions are set by the 1984 Sugarcane and Sugar Act.

21/ The Office of the Cane and Sugar Board pushed forward with the amendment to the Act by publishing an announcement in the Royal Gazette with effect from December 24th, 2022. In response, sugar mills brought a case to the Administrative Court, with the Thai Sugar Millers Corporation acting on their behalf.

22/ There are 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), organized into 169 SDG Targets that are regarded as universal, interconnected, and mutually supportive. Progress towards meeting the SDGs is assessed through 247 indicators. Overall, the SDGs are grouped into 5 primary areas (the ‘5Ps’): (i) people, which is focused on the eradication of poverty and hunger, and the reduction of social inequality; (ii) planet, or the protection of natural resources and the preservation of the climate for future generations; (iii) prosperity, which is concerned with promoting well-being for all in harmony with the natural environment; (iv) peace, which is concerned with the maintenance of stable coexistence among all peoples, and the preservation of peaceful and inclusive societies; and (v) partnership, or the promotion of cooperation between all parts of society to push for sustainable development (source: Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council).

23/ The BCG model has 3 components. The ‘B’ is for the bioeconomy, which attempts to ensure that bio-resources are used with maximum efficiency, for example by raising outputs, maximizing added value, and emphasizing biodiversity. This is linked to the circular economy, the ‘C’, which closes the economic loop to ensure the greatest possible reuse of resources. This thus includes making full use of products across their entire lifecycle and then reusing or recycling these. Both of these are then subsumed into the ‘G’, that is, the green economy. This aims to address problems with pollution and to sustainably reduce human impacts on the world (source: the National Science and Technology Development Agency).