EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The palm oil industry is expected to expand, with supply projected to increase during 2025-2026. This is supported by (i) higher yields per rai due to favorable weather conditions, particularly in the southern region, (ii) higher oil content from harvesting at the optimal palm tree age, and (iii) strong harvesting incentives driven by attractive fresh palm fruit prices. However, in 2027, the overall supply of oil palm and palm oil is expected to contract due to the anticipated return of El Niño conditions. On the demand side, consumption is projected to accelerate during 2025-2027, primarily driven by (i) domestic demand from downstream industries, particularly the food, chemical, and oleochemical industries, which are expected to recover alongside economic and tourism sector improvements, (ii) growth in the transportation sector supported by accelerated infrastructure investments, and (iii) government measures promoting biodiesel consumption, with major automotive manufacturers expected to develop diesel engines compatible with higher biodiesel blends. However, export growth may remain moderate despite support from trading partners of Indonesia and Malaysia shifting to imports from Thailand as an alternative. The ongoing export restrictions by competing countries are expected to sustain high palm oil prices beyond 2024.

Krungsri Research view

Between 2025 and 2027, the palm oil industry is expected to expand due to increased production driven by favorable weather conditions from La Niña impacts, which will lead to higher yields per rai of oil palm. Meanwhile, domestic demand will be supported by purchasing power in the food, chemicals, oleochemicals, and biodiesel industries, which will likely drive up the price of fresh palm fruit, benefiting business performance and profitability. However, the industry still faces risks from increasingly stringent non-tariff trade barriers, competition for raw materials from extraction plants, and excess production capacity, which is expected to remain high.

-

Palm growers: Income will tend to rise supported by increased outputs, recovering domestic demand, and still-high prices bolstered by government measures. However, farmers still face many risk factors, including potential outbreaks of plant diseases that may affect yield per rai and persistently high fertilizer costs.

-

Crude palm oil mills: Business performance is expected to gradually improve, supported by a recovering domestic market, an increase in tourism, the expansion of the commercial transportation sector, and government measures promoting biodiesel consumption. However, overall production capacity has historically exceeded the volume of fresh palm fruit available in the market, leading to intense competition for raw materials. This has affected production costs and pressured profit margins, particularly for small-scale extraction plants that lack direct connections to refineries or downstream industries such as refined palm oil, biodiesel, oleochemicals1/, and by-products from production, including refined glycerin2/, phase change materials (PCM)3/, and fatty alcohols4/.

-

Palm oil refiners: Business performance is expected to continue growing, driven by an anticipated 3.0%-4.0% increase in demand for crude palm oil for refining. This growth aligns with the expansion of the food industry, supported by the recovery of the tourism, hotel, and restaurant sectors. Additionally, the oleochemical industry is expected to see increased demand for crude palm oil and palm fat (a by-product of the refining process) in line with the resurgence of consumption in related industries such as detergents, soaps, pharmaceuticals, and cosmetics.

-

Traders in crops used in the production of vegetable oil (oil palm collection yards): Revenue is expected to rise in line with the increasing supply of fresh palm fruit, driven by La Niña impacts. Moreover, collection centers hold stronger bargaining power than oil palm farmers, most of whom are small-scale growers reliant on selling their fresh palm fruit through these intermediaries.

Overview

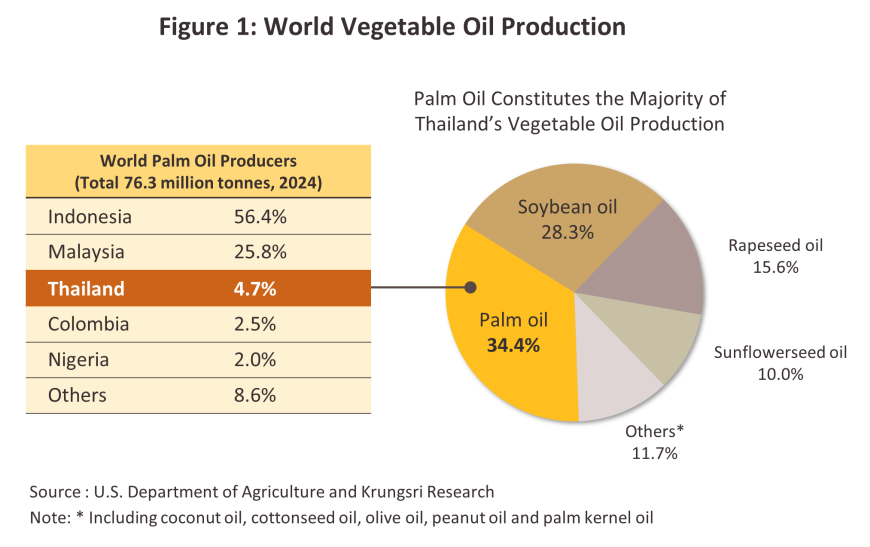

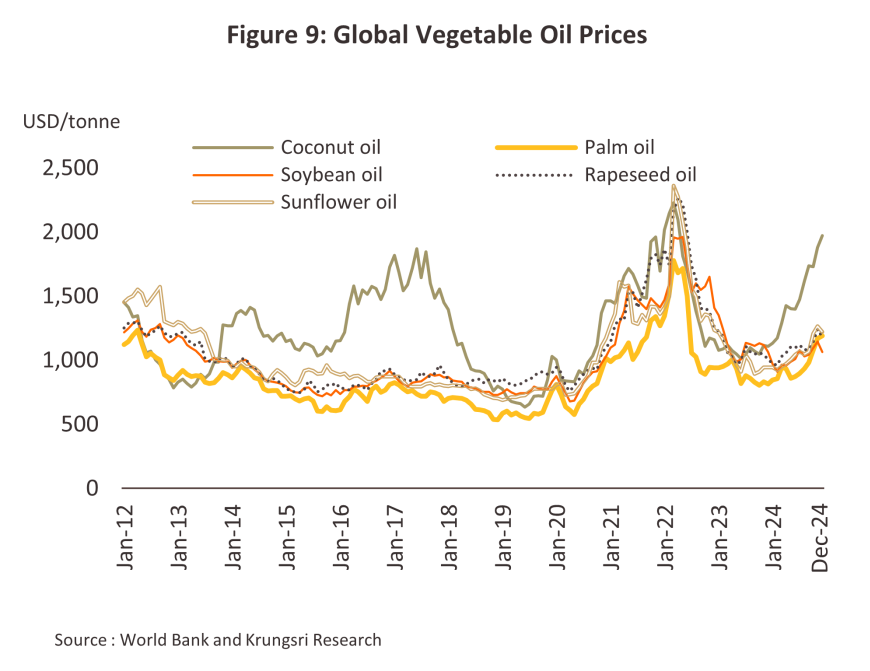

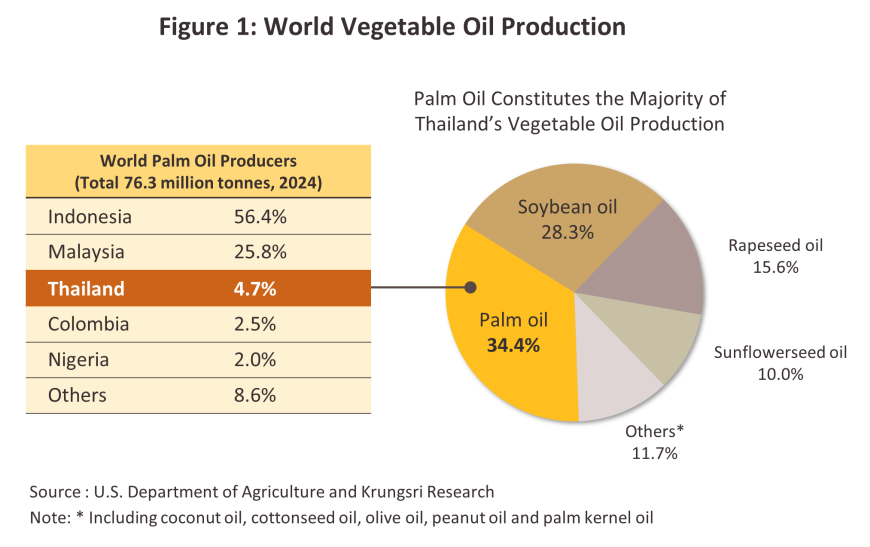

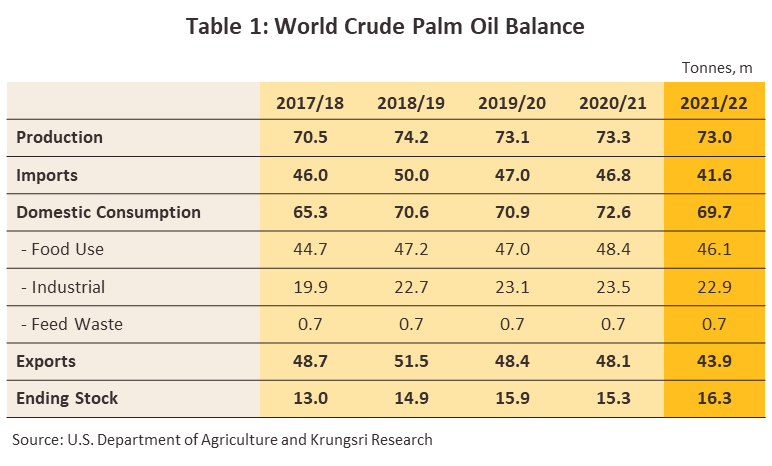

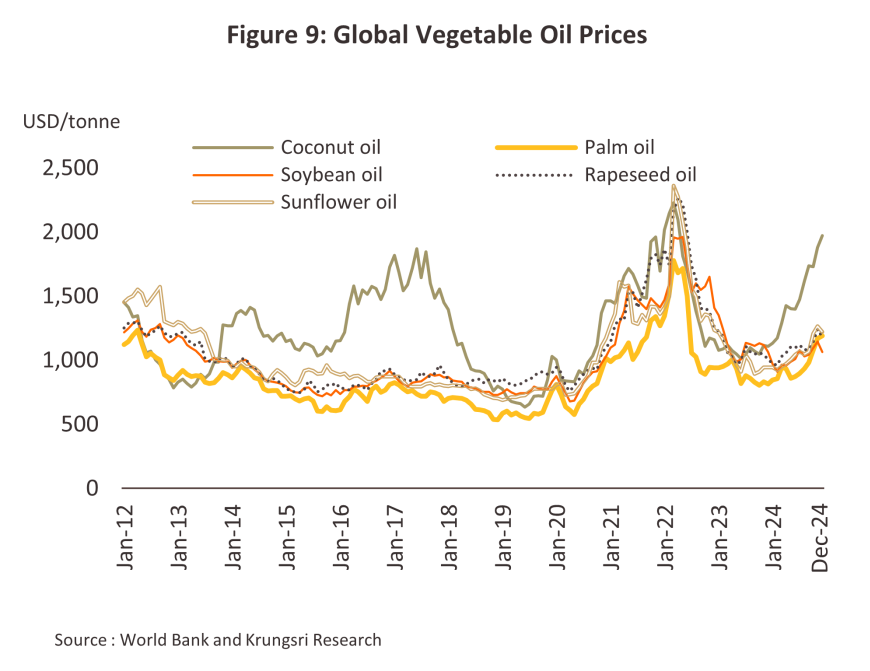

Palm oil5/ is the cheapest vegetable oil to produce, partly because it generates yields that are 5-10 times6/ higher than those of other oil crops such as soy, rapeseed, sunflower, coconut and olive. As of 2024, global production of palm oil totaled 76.3 million tonnes, while worldwide consumption total of 75.1 million tonnes, figures that represent respectively 34.4% and 34.6% of total global vegetable oil production and consumption. The ASEAN region is the principal palm oil producing area, and because they are the most important suppliers to world markets, Indonesia and Malaysia play a significant role in setting prices on global exchanges; in 2024, Indonesia produced some 43.0 million tonnes of CPO annually, while Malaysia contributed another 19.7 million tonnes to world markets and so combined, these accounted for 82.2% of global output. Naturally, these two countries are also the world’s major exporters, producing 86.6% of the CPO bound for international markets. In terms of imports, India is the single biggest market, taking 20.7% of world imports in 2024. India is followed in size by China (10.2%), the European Union (8.9%), and Pakistan (7.2%). Over the five years between 2020 and 2024, global demand for CPO for both direct consumption and for production of energy grew by an average of 1.5% per year, while output has risen at an annual rate of 1.1%. By the end of 2024, accumulated stocks of CPO stood at a total of 15.9 million tonnes (Figure 1 and Table 1).

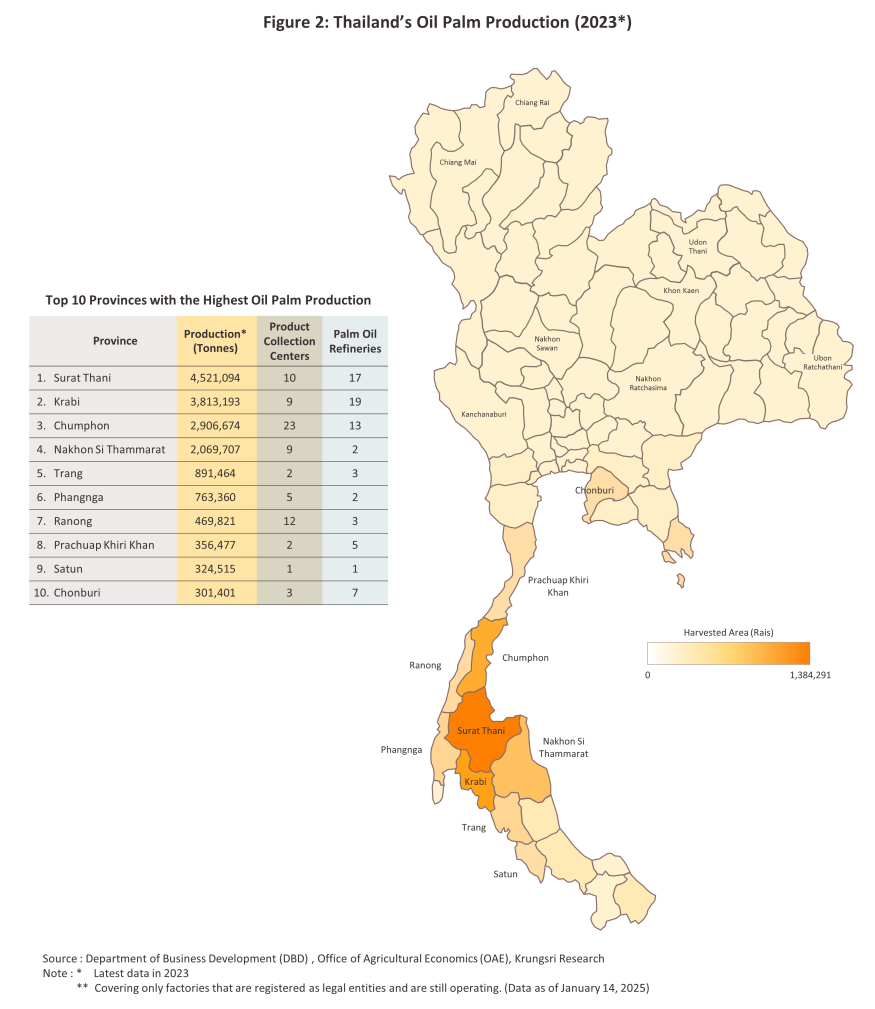

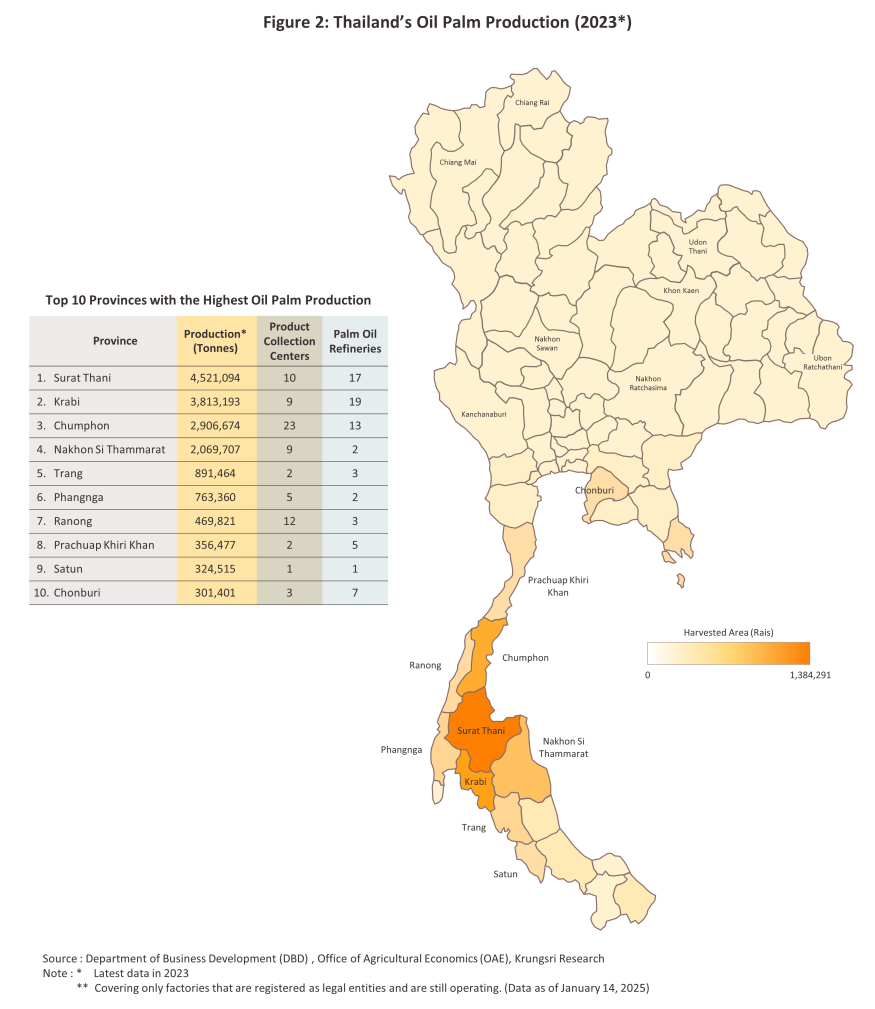

In 2024 although Thailand stood in third place in the world palm oil production rankings, its output came to only 4.7% of the global total and so, unlike Indonesia and Malaysia, Thai influence on global prices is only slight. The domestic industry is very geographically concentrated, and 85.9% of the harvested area* covered by oil palm plantations is in the south of the country7/, clustered in particular in the provinces of Surat Thani, Krabi, and Chumphon, which together are home to some 57.4%* of the country’s oil palm plantations. In order of importance, the remainder is found in the center, the northeast and the north of the country (Figure 2). In 2024, The total harvested area of palm came to 6.3 million rai (+1.5%). In the same year, national output totaled 18.6 million tonnes of oil palm (+1.9%)8/, which was converted into 3.3 million tonnes of CPO (-1.6%) (source: The Office of Agricultural Economics, Department of Internal Trade).

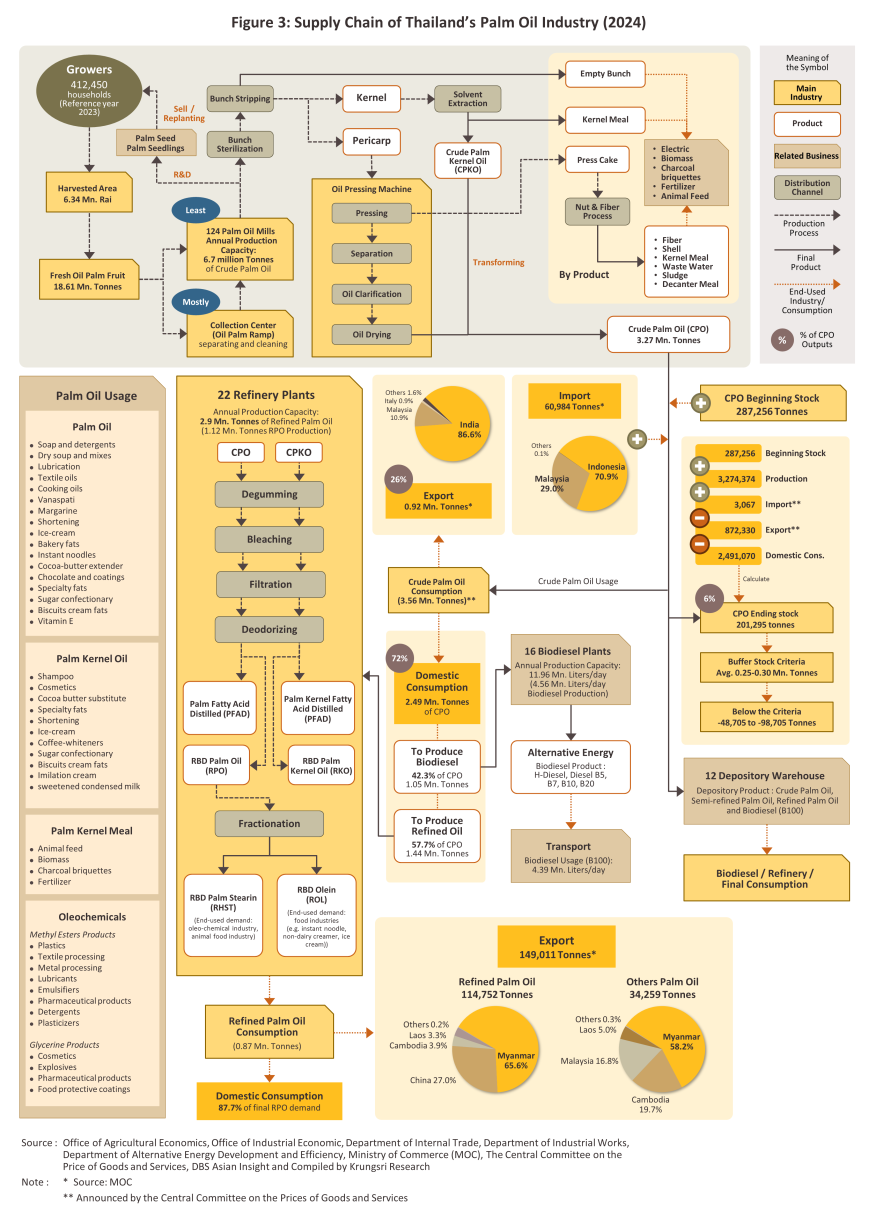

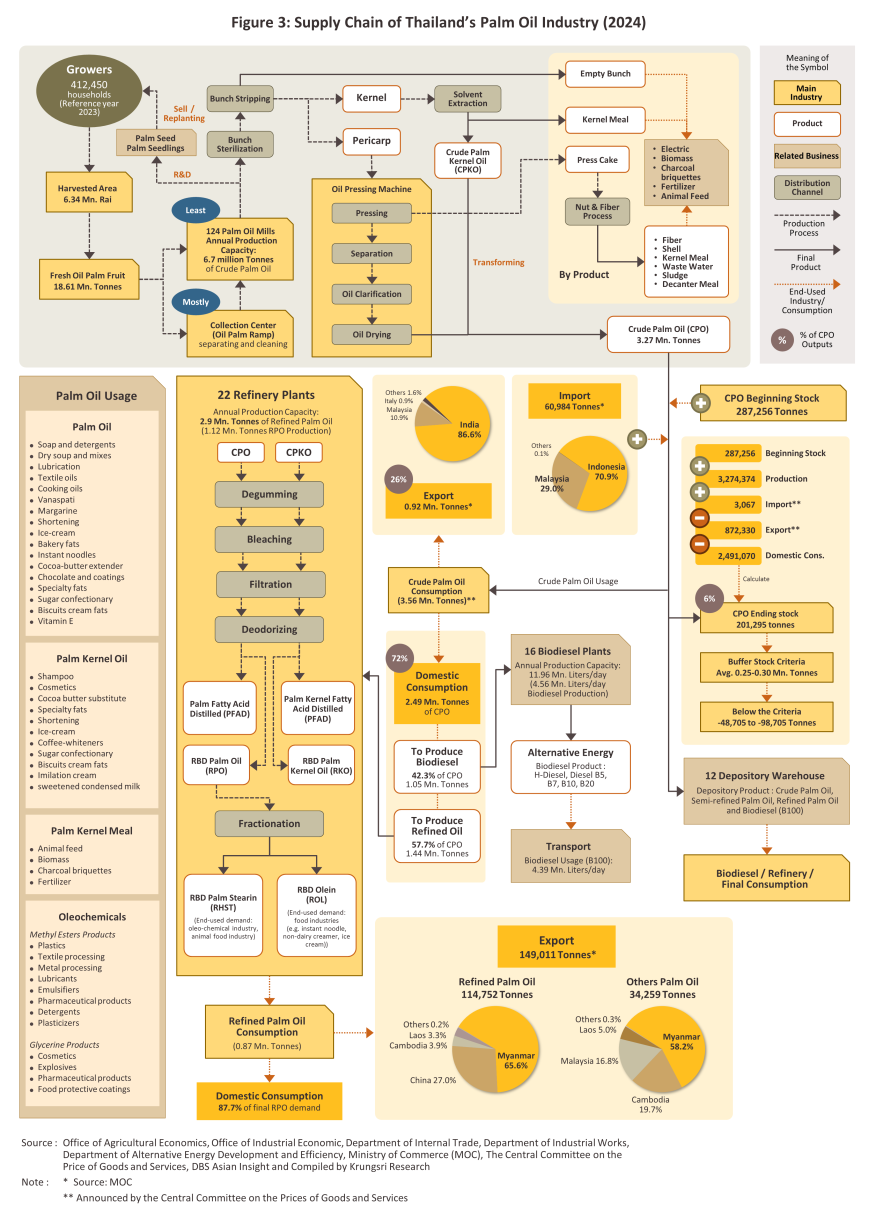

One strength of the Thai palm oil sector is its comprehensive supply chain (Figure 3). This is composed of the following:

-

Oil palm grower (upstream production): This is centered on the roughly 0.41 million households across the country that grow oil palm, the majority of which are small-scale producers. Large producers typically invest in operate their own CPO mills.

-

CPO mills (midstream production): This is based on mills that output CPO. Currently there are 124 of these in Thailand (source: Department of Internal Trade), and the Office of Industrial Economics (OIE) estimates that the country’s installed processing capacity comes to around 6.7 million tonnes of CPO per year. Large operators of oil mills may also invest in their own palm oil plantations, growing seedlings and developing new palm cultivars. Processing plants also produce a wide range of by-products from the milling of palm and these may be used to generate additional income; kernel meal is used as an animal feed and the palm shells, fiber and other waste may be used for the production of biomass energy or organic fertilizer.

-

Palm oil refiners (downstream production): The final stage of the industry supply chain is comprised of palm oil refineries, of which there are 22 in Thailand. The OIE reports that these have an annual production capacity of 3.0 million tonnes. Large operators are often connected through their investments to other parts of the palm supply chain including, for example, CPO mills and the production of vegetable oils

-

Other industries: These help to absorb additional supply, and include biodiesel refineries, food processors, and the chemicals and oleochemicals industries, which serve as raw materials for cosmetics and various daily cleaning products.

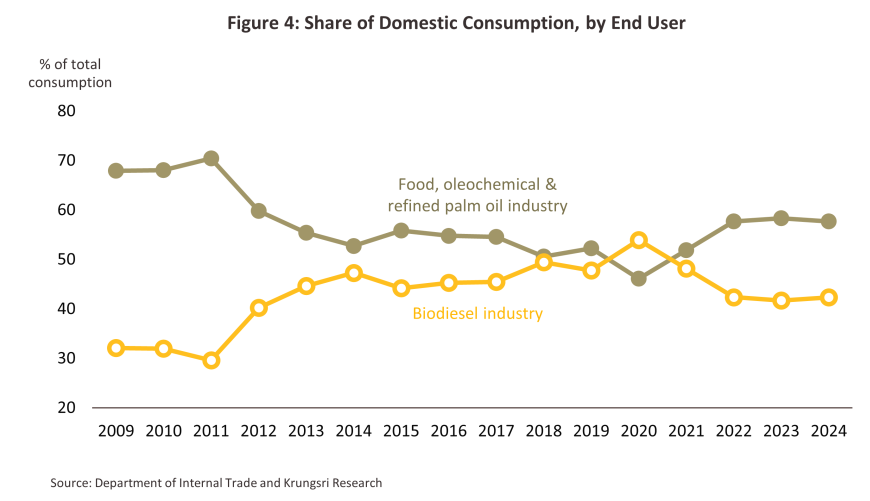

As of 2024, around 72% of Thailand’s output of CPO was distributed to the domestic market (Figure 3).

-

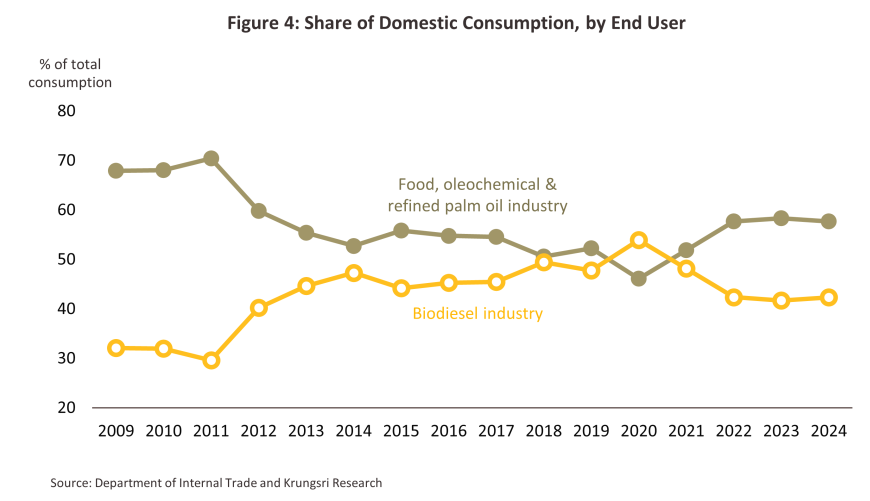

Production of refined palm oil: In 2024, 58% of CPO was converted into refined palm oil, which is then used in: (i) the food industry, where it is a component in snacks, instant noodles, condensed milk, creamer, margarine, shortening, ice cream, food supplements and vitamins, and chemical and oleochemical products; and (ii) the manufacture of other products such as soap, cosmetics, shampoo, and lubricants (Figure 3).

-

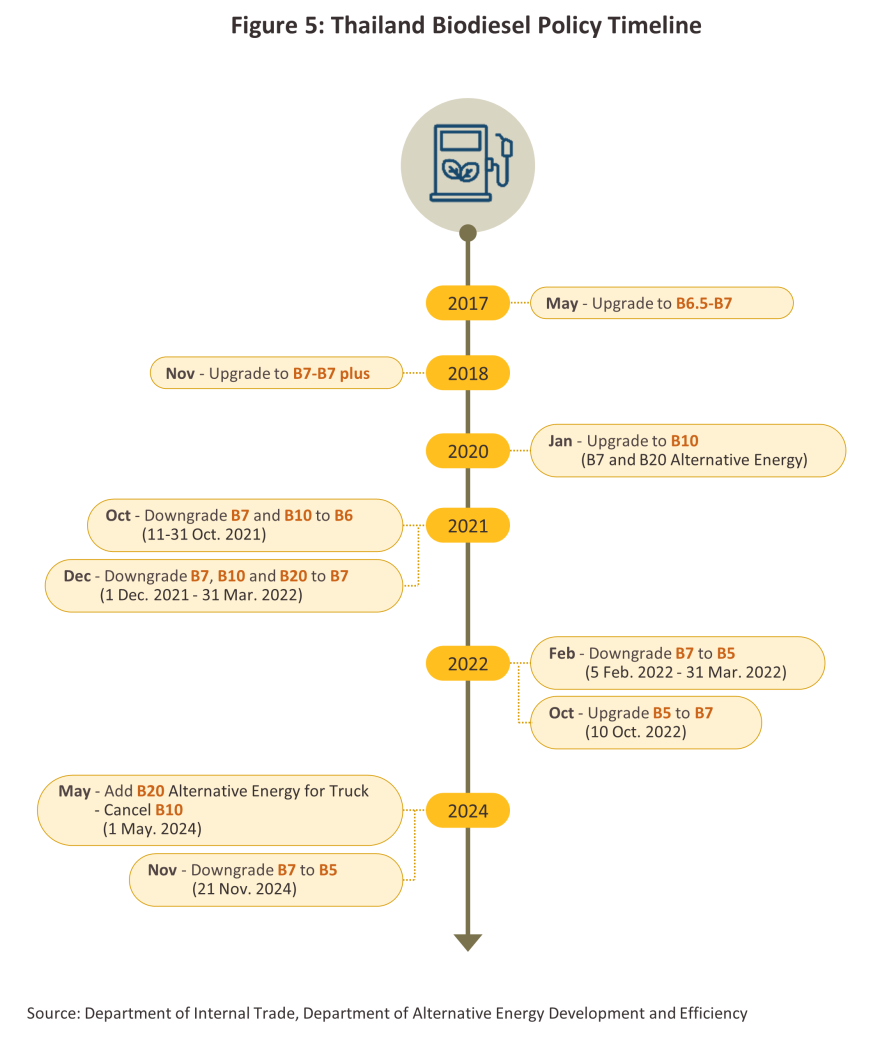

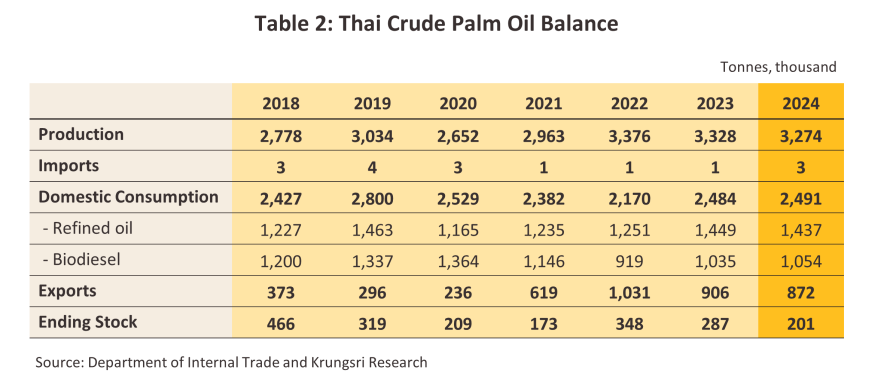

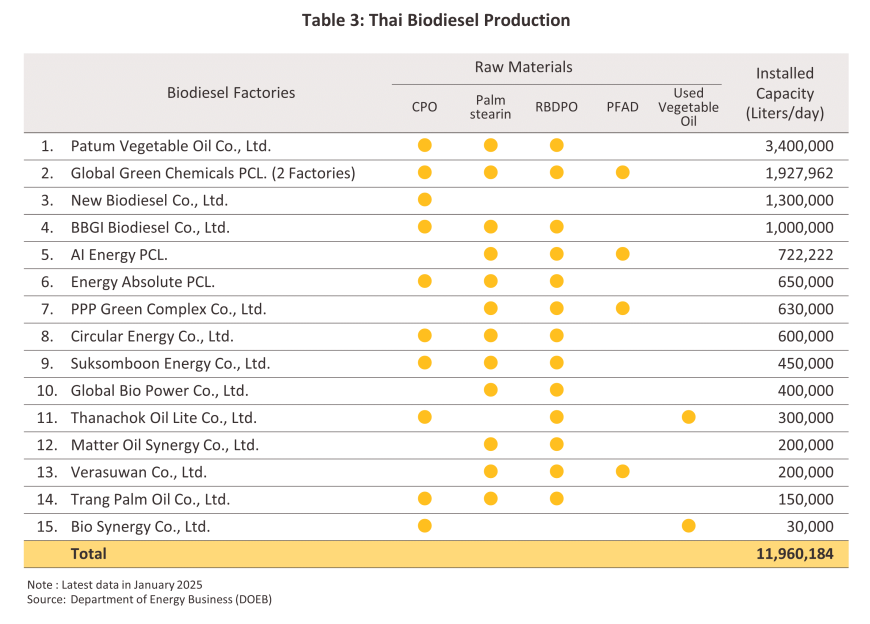

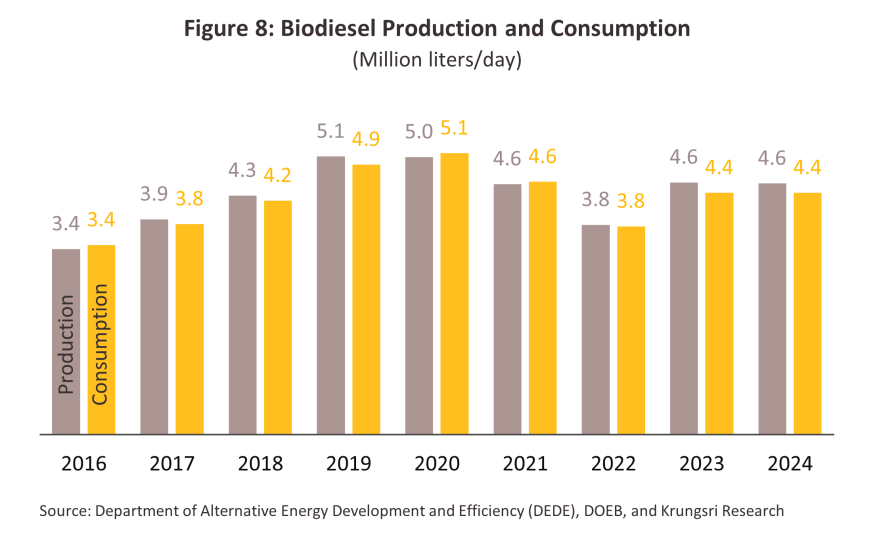

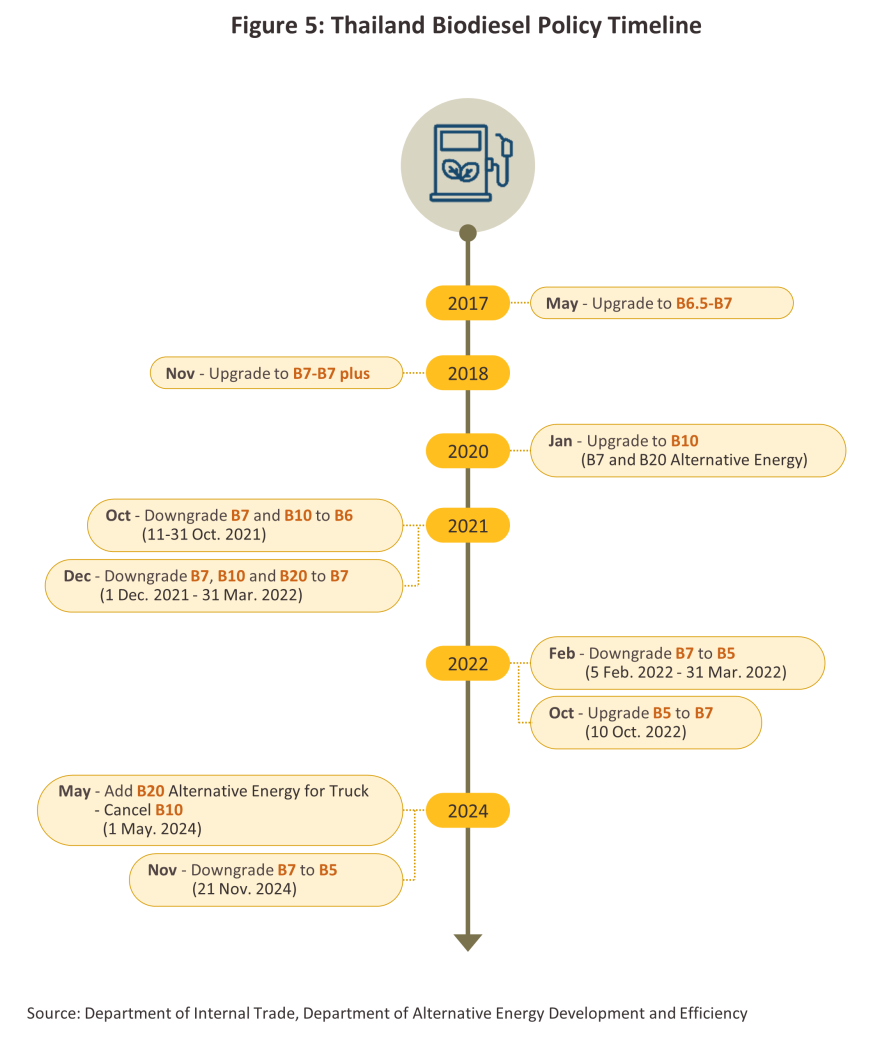

Production of biodiesel (B100): The remaining 42% of the market is accounted for by the production of biodiesel (B100), which is then mixed with mineral diesel for sale as a transport fuel. The authorities typically adjust the amount of B100 included in the diesel mix to match each season’s output of CPO. Thus, in 2021, the biodiesel blend was reduced from B10 to B7 and further from B7 to B59/ due to a significant increase in domestic palm oil prices and a decline in national stock levels. Subsequently, in 2023, the blend was raised from B5 back to B7 in response to a relatively high surplus of crude palm oil supply. (Figure 5).

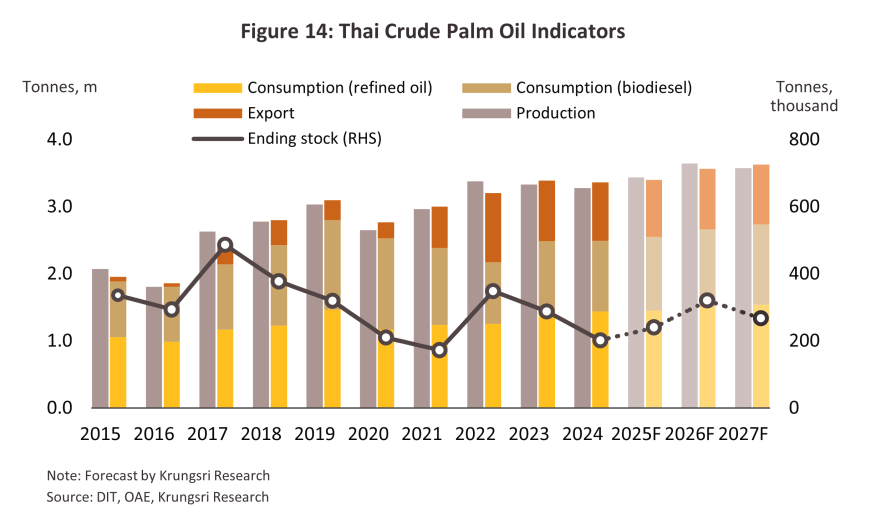

In 2024, Thailand exported approximately 26% of its total crude palm oil production. The annual export volume depends on surplus production at any given time, with the government implementing measures or initiatives to promote crude palm oil exports periodically to alleviate domestic oversupply. Similarly, imports are permitted only during periods of supply shortages, such as when crude palm oil stock levels fall below the buffer stock threshold, which is set at approximately 0.25-0.30 million tonnes10/. At the end of 2024, Thailand’s remaining crude palm oil stock stood at 0.20 million tonnes, accounting for 6% of total production. This domestic stock levels significantly influence palm oil prices.

-

The purchase price of fresh oil palm from farmers11/ is set by the Central Committee on the Prices of Goods and Services (CCP) (operating under the Department of Internal Trade within the Ministry of Commerce), which specifies the reference prices for mixed grades of palm fruits according to their oil content. Since 2017, the regulations have stated that mills should buy only fruits that are at least 18% oil since by setting a minimum oil content, it is hoped that the quality of Thai palm oil will increase, and by harvesting fully ripe fruit, yield will increase, and farmers will be able to sell their oil palm fruits at a higher price.

-

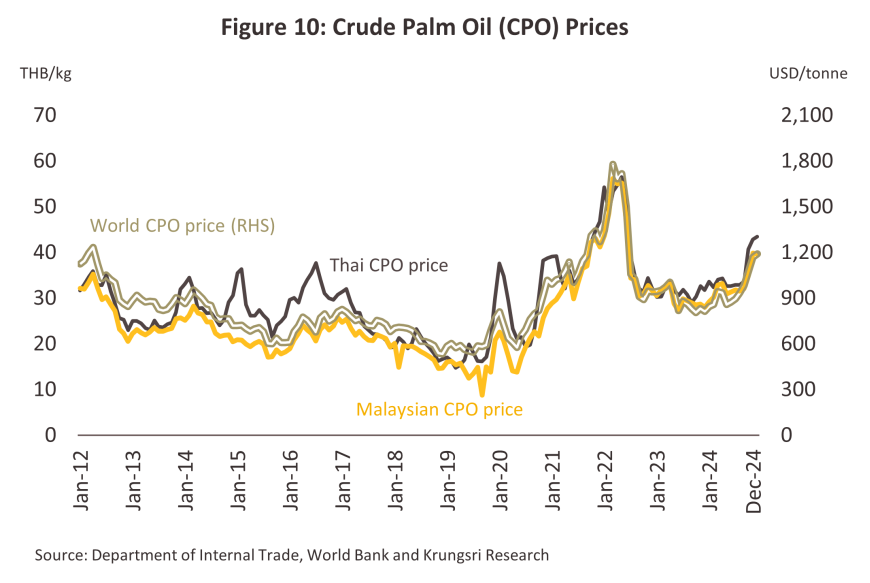

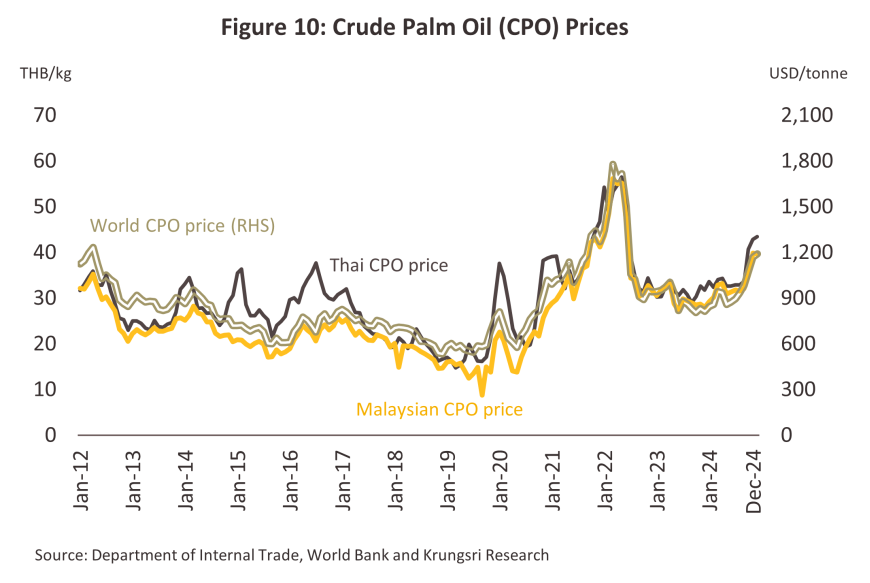

The CPO price is set with reference to the cost of inputs (i.e., the domestic cost of fresh oil palm) and trends in the price of CPO on world markets.

-

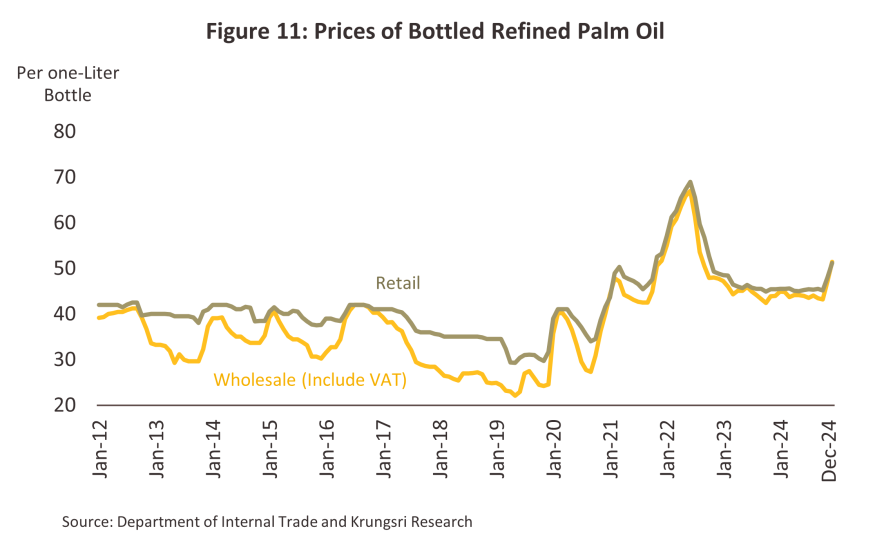

In the past, the retail price of bottled refined palm oil was controlled by the Department of Internal Trade but since February 2019, this has allowed the market to determine prices12/, and these thus tend to move with the cost of inputs.

Situation

Domestic palm oil supply expanded in 2024 on the incentive effects of higher prices, while a better economic outlook and in particular rising tourist arrivals helped to boost demand from the travel and transport industries for palm oil used as a fuel. Nevertheless, higher prices for palm fruits pushed up the cost of manufacturing refined palm oil and this then dragged on household demand. At the same time, exports edged up slightly on stronger demand from Malaysia, a major overseas market for Thailand.

-

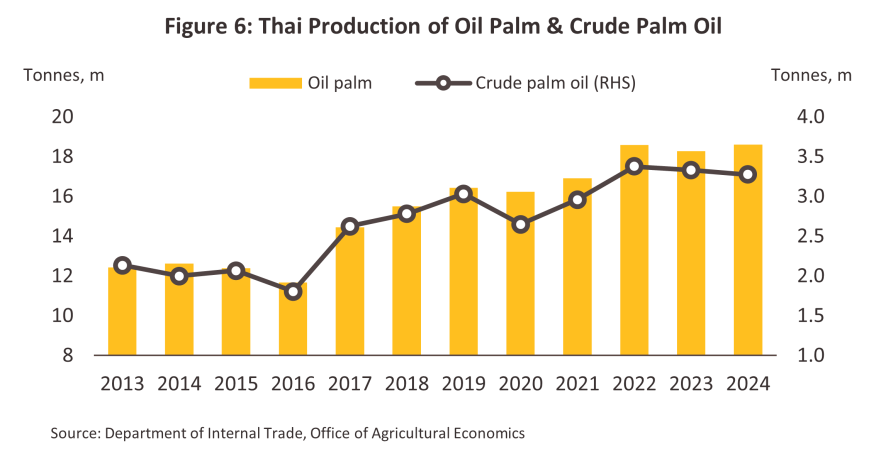

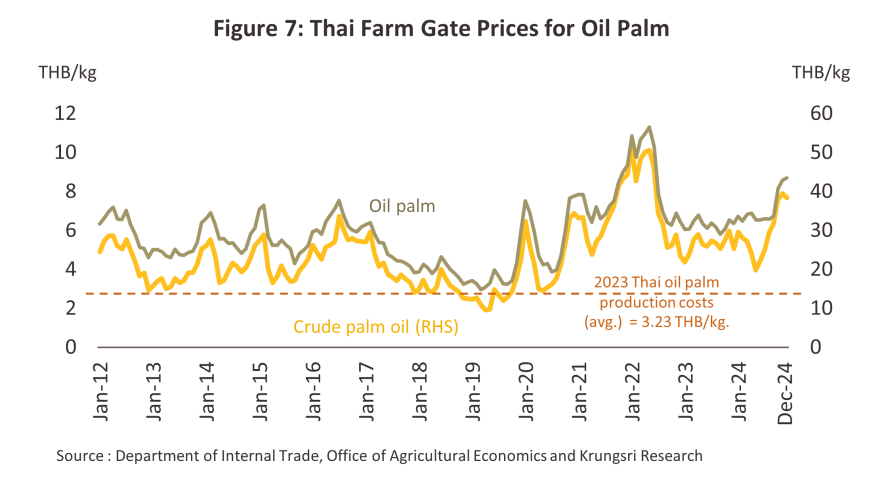

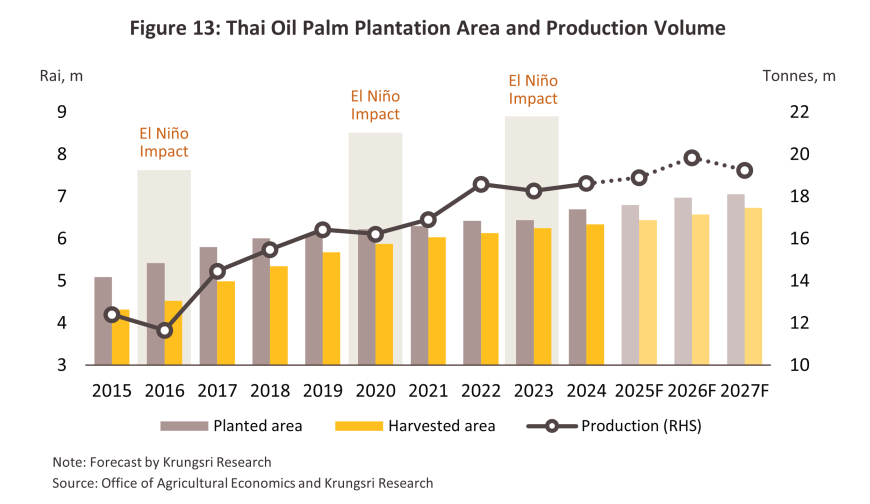

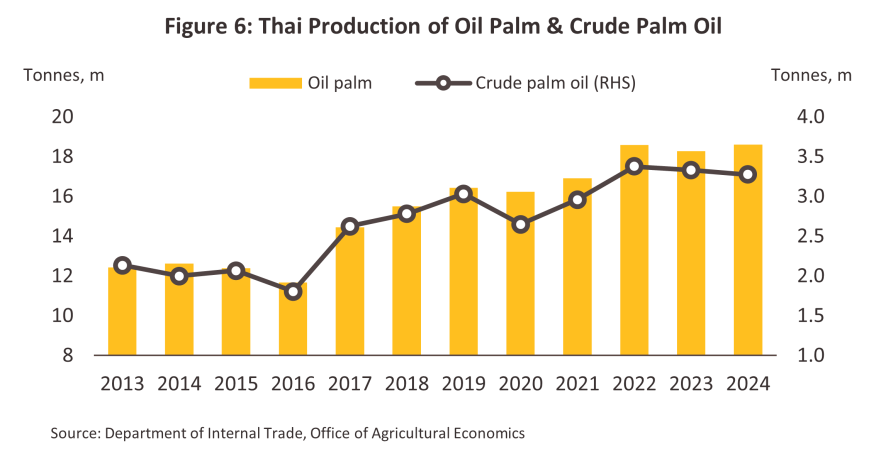

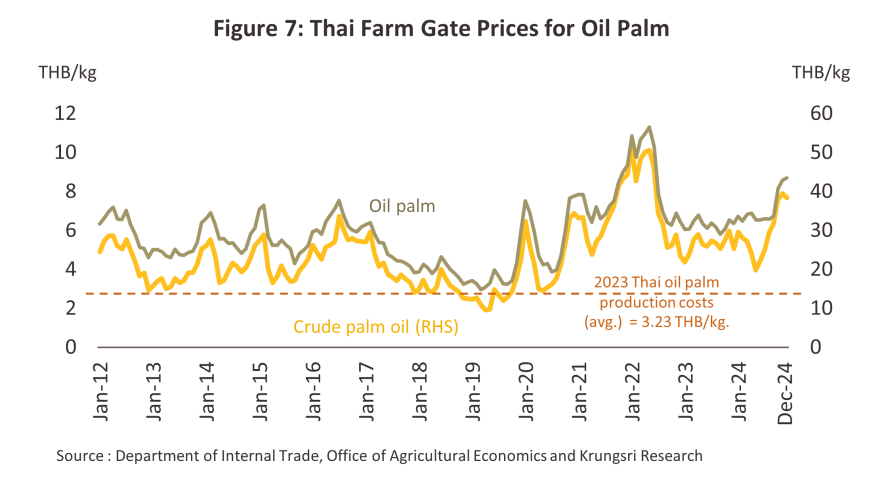

Domestic palm fruit and palm oil output hit new highs in the year (Figure 6). In detail, the Office of Agricultural Economics estimates that in 2024, the total area yielding oil palm fruits increased 1.5% to 6.34 million rai and as such, outputs climbed to 18.6 million tonnes, a 1.9% improvement on the previous year’s 18.3 million tonnes. Increases were driven by: (i) worries over the possible impacts of the emergence of El Niño conditions in the first half of the year; (ii) increased outputs from trees planted prior to 2021; (iii) high prices that encouraged farmers to care better for their plantations and to harvest according to best practices; and (iv) the setting of an attractive minimum purchase price by the government13/. Through the year, prices for fresh palm fruits averaged THB 5.9/kg (+11.4%), significantly above average production costs of THB 3.2/kg (Figure 7). However, total output of crude palm oil (CPO) slipped -1.6% to 3.27 million tonnes, down from 3.33 million tonnes in 2023 (Table 2). Production suffered from the onset of an El Niño and the resulting hot weather and lower than average rainfall in the first half of the year, and as a consequence, a number of plantations had restricted access to water, causing some fruits to shrink or to ripen prematurely in the sun14/. Alongside this, some trees were also hit by outbreaks of basal stem rot disease (caused by Ganoderma boninense) and so the quality of the harvest declined, cutting the oil content of fruits by -3.2% to just 17.7%.

-

As of year-end 2024, increased consumption of biodiesel resulted in a -29.9% decline in domestic CPO stocks, and with these at just 0.2 million tonnes17/, prices for both palm fruits and palm oil rose.

-

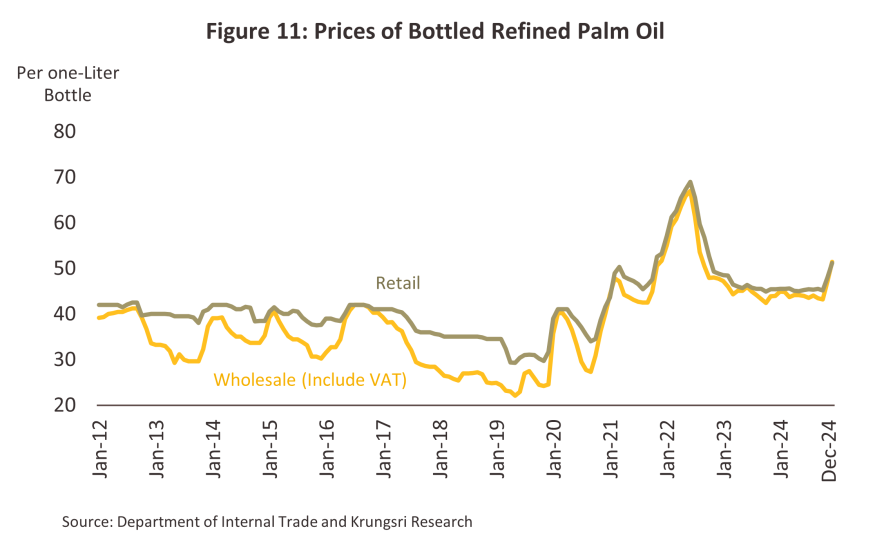

Following the setting of new prices by the Energy Policy and Planning Office (EPPO) and an increase in those paid by mills18/, prices for fresh palm fruits rose from THB 5.9/kg at the start of 2024 to THB 7.7/kg at its end, with average prices across the year thus up 11.4%. This then increased CPO production costs, raising market prices for this from THB 33.6/kg to THB 43.4/kg through 2024, or an average increase of 13.5% (Figure 10). Likewise, retail prices for bottled palm oil went from THB 45.5/liter to THB 51.2/liter (Figure 11), while average export prices for palm oil products also climbed 6.1% in 2024, mirroring the 8.7% rise in global prices to USD 963/tonne. The latter was partly caused by the decline in global inventories as demand for use in industry and food processing ticked up by respectively 2.9% and 0.3%, although in Indonesia, these jumped by respectively 13.4% and 5.0%.

-

As a result of the combined effects of shrinking domestic stocks and higher prices, the Committee on Energy Policy Administration announced in November that to maintain stocks and to ensure price stability, the standard diesel mix would be cut from B7 to B5 (or from 7% to 5% biodiesel).

Outlook

Over 2025-2027, domestic palm fruit outputs are forecast to rise by 1.0-2.0% annually, while the output of crude palm oil should be up by 2.5-3.5% pa.

-

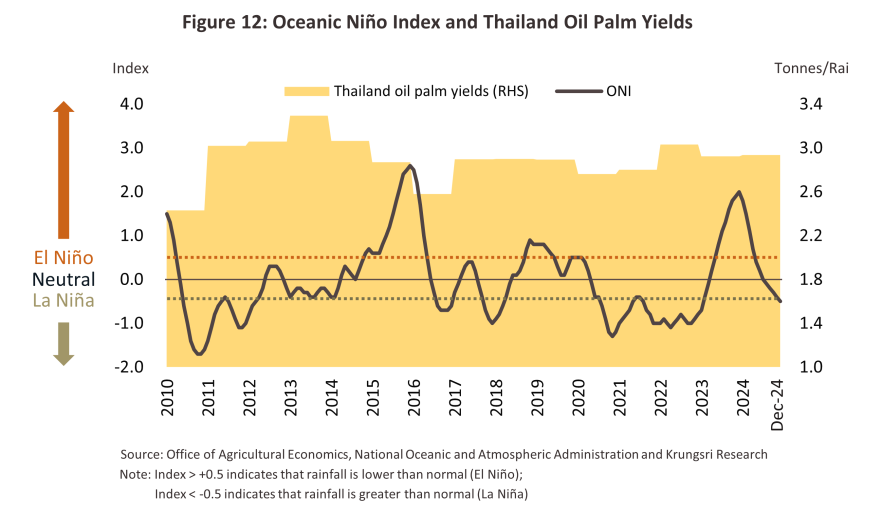

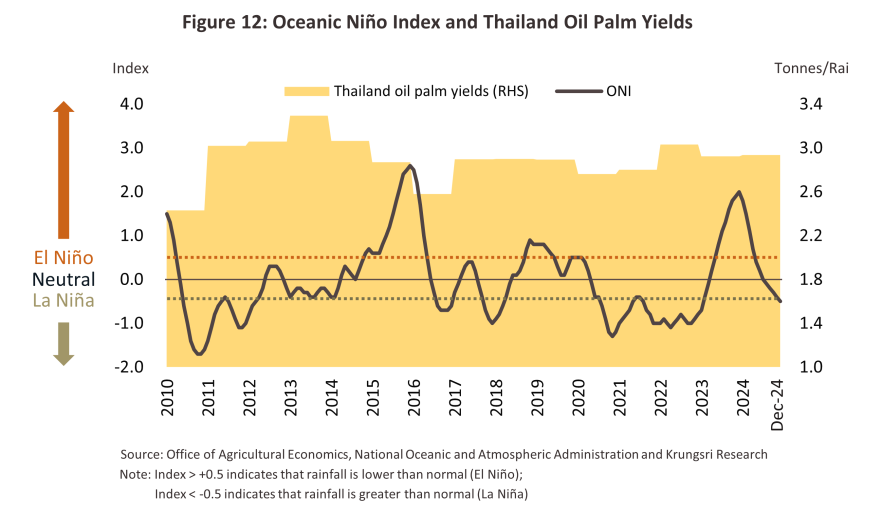

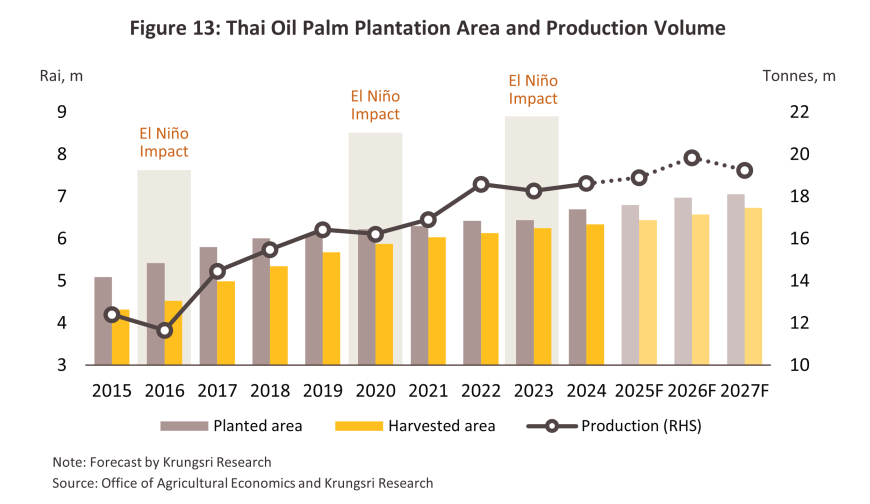

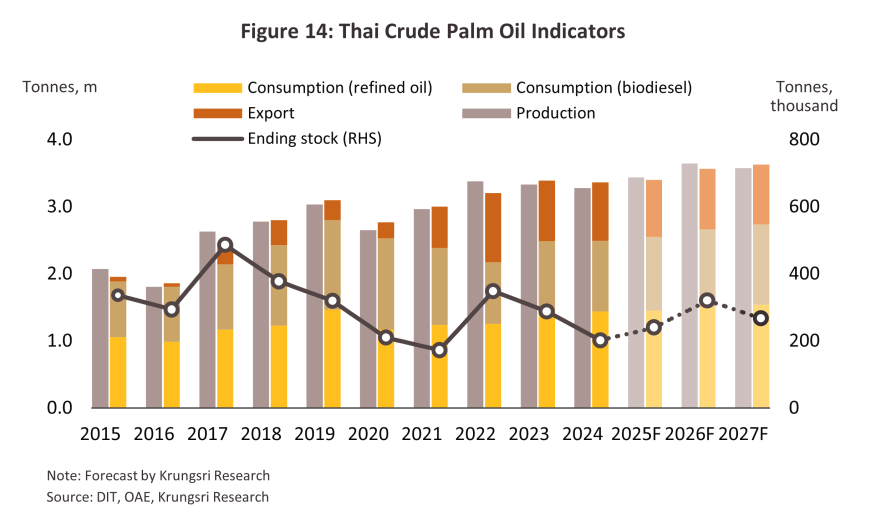

The supply of palm fruits is expected to grow by 2.5-3.5% per year over 2025 and 2026. This will come as a result of: (i) the likely emergence of La Niña (Figure 12), which will bring more favorable climatic conditions and higher per-unit yields through these two years; (ii) a 1.5-2.5% annual expansion in the area planted with oil palm trees (up by 0.1-0.2 million rai), while a greater number of trees planted before 2022 are now entering a period when they deliver higher yields19/; and (iii) higher prices that will continue to incentivize farmers to care better for their plantations and to maximize outputs. With outputs rising (Figure 13), Krungsri Research thus sees output of CPO climbing by 5.0-6.0% annually in 2025 and 2026. However, the possible return of El Niño conditions in 2027 will eat into palm yields and thus these are expected to fall back by between -2.0% and -3.0%, resulting in a decline in CPO production of -1.5% to -2.5% (Figure 14).

-

-

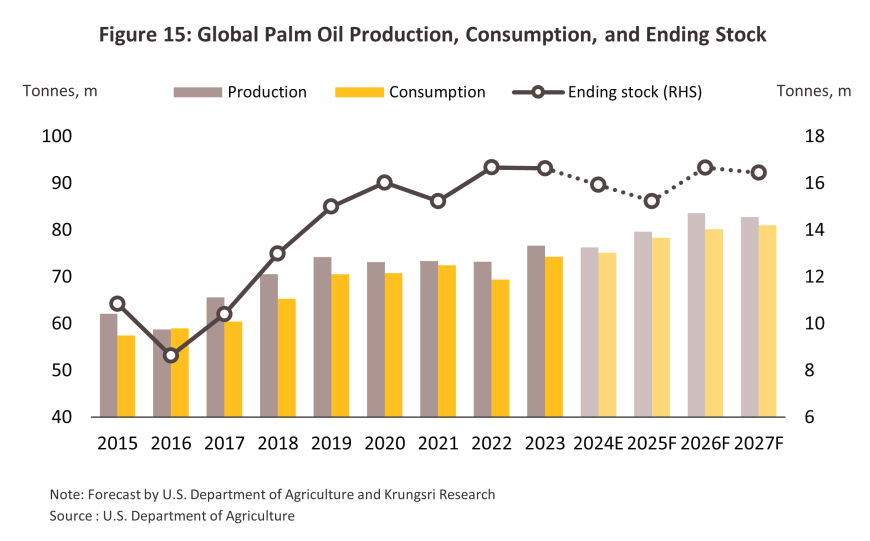

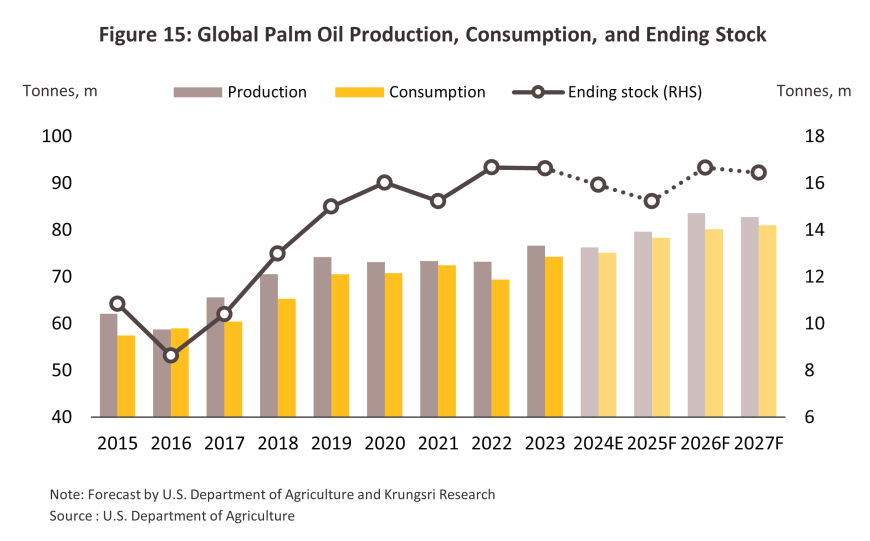

The global supply of CPO is forecast to expand by 2.5-3.5% over the three years from 2025 to 2027, in line with global oil palm production growth projected at 4.0-5.0% annually during 2025-2026, benefiting from favorable weather conditions due to the La Niña phenomenon, which is expected to boost oil palm yield per hectare. However, the possible El Niño phenomenon, which is expected to cause drought in 2027 will again reduce per-unit yields by between -0.5% and -1.5% (Figure 15). Overall, the global industry will also continue to be impacted by: (i) labor shortages in the major palm-producing nations of Indonesia and Malaysia, which will affect the harvest in these countries; and (ii) growing demand for palm oil for use as a transport fuel in producing nations20/, both because of its environmental benefits and to reduce dependency on energy imports, which with geopolitical tensions high are subject to a significant degree of price volatility. This, combined with the need to secure supply to the domestic market, has then encouraged some of Thailand’s competitors to periodically impose export restrictions. Global demand for CPO is also expected to strengthen by 2.5-3.5% per year over the next three years, adding to pressure on global inventories and as such, stock levels will remain low. Given this balance of supply and demand, global CPO prices will trend upwards, thereby helping to keep domestic prices for oil palm and palm oil above production costs.

-

Domestic consumption of CPO will rise by 2.5-3.5% annually over 2025-2027 on greater demand from downstream businesses, in particular those in the food processing, chemicals and oleochemicals, and transport industries, as these will likely benefit from continuing recovery in tourism and overall economy.

-

Refined palm oil: Annual demand for crude palm oil for refining is forecast to expand by 2.0%-3.0%. This improvement will be driven by: (i) recovery in the tourism, hotel, and restaurant industries, which will then feed into greater demand for goods from food processors; (ii) firmer demand for palm oil/palm fats (obtained from the palm oil purification process) from players in the oleochemical industry as consumption of products such as detergent, soap, medicines, and cosmetics firms up; and (iii) official moves to boost domestic demand for CPO and to further develop the oleochemicals industry, as laid out in the 2018-2037 plan for the reform of the Thai oil palm and palm oil industry.

-

Biodiesel production: Demand for biodiesel should continue to strengthen by an average of 4.0%-5.0% annually to around 4.6-4.8 million liters/day. (i) Increasing demand for vehicles used in transportation due to: (i.i) recovery in economic activity, which will be attributable especially to the rise in tourist arrivals to some 41 million by 2027, expansion in the e-commerce industry, and as per the government’s plans for improved transport integration, increased spending on infrastructure projects that will then support greater use of commercial vehicles, including trucks and pickups; and (i.ii) an expected 3.0-4.0% annual rise in the number of diesel vehicles on Thai roads. (ii) Government measures to promote greater consumption of biodiesel and to maintain stability within the palm oil industry will lift the market. (iii) Major auto manufacturers are developing new engines that are capable of running on fuels containing a greater proportion of biodiesel, and these will be fitted to pickups, SUVs, trucks, and other large vehicles. However, the implementation of Euro 6 standards for diesel engine vehicles of all sizes, expected to be effective in 2026, may increase overall transportation costs, potentially impacting demand, despite some positive effects on biodiesel demand due to its low sulfur content and reduced emissions, such as lower carbon monoxide (CO), particulate matter (PM), and hydrocarbons (HC).

-

Annual exports will inch up by only 0.5-1.5%. The market will be affected by: (i) Indonesia’s 2025 hike in CPO export duties from 7.5% to 10%, which officials hope will finance the move from B35 to B40 diesel; and (ii) the decision by Malaysia to develop its palm oil supply chain and to bring this into alignment with the requirements laid out in the EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR) by limiting the areas of oil palm cultivation and improving provenance checking and product traceability (source: KAMI EFI, 2024). Thanks to the impact of these developments and the need to replace lost supply from Indonesia and Malaysia, Thailand will have greater space to operate in CPO export markets, though growth rates will nevertheless remain somewhat limited since any expansion in supply by Thai producers will be largely absorbed by recovery in the domestic market. This will come especially from the food processing, travel, and transport industries, which will benefit from continuing growth in tourist arrivals, while the risk of a worsening trade environment and ongoing geopolitical stresses will weigh on the outlook for the industry globally.

-

Year-end CPO stocks will average 0.24-0.32 million tonnes over 2025-2027, up from 0.2 million tonnes at the end of 2024. Stock levels will benefit from stronger domestic supply, especially in 2025 and 2026 as the weather improves (in particular in the south of the country), high prices encourage growers to lavish more care on their trees, and the age of plantations helps the oil content of fruits to rise to an optimum level. However, the supply of oil palm and palm oil is likely to slip again in 2027 if, as expected, El Niño conditions return.

-

Prices will be lifted by the tightening of supply by Thailand’s competitors, which will run against a general strengthening of demand in global markets. These trends will be amplified by the increasing move to absorb excess domestic supply by raising the quantity of biodiesel mixed into standard diesel. As a result, prices for oil palm and palm oil will trend upwards from their 2024 level, with prices for fresh palm fruits expected to hit THB 7-8/kg (up from an average of THB 6.0/kg in 2024).

Potential risks and headwinds that may pose a challenge to the industry will include the following.

-

Changes to government policy may have a significant impact on the industry since government agencies (including the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives, the Ministry of Industry, the Ministry of Energy, and the Ministry of Commerce) are involved both directly and indirectly across industry supply chains, from the upstream production of inputs through to the downstream distribution of finished goods. This then exposes players to risk arising from policy discontinuities and the potential disruptions arising from changes in the political environment.

-

Energy prices are being pushed up by geopolitical tensions, including the war in Ukraine and the violence between Hamas and Israel, and this may undercut demand for diesel from the transport sector.

-

Competition remains stiff from alternative products, new entrants to the market, and existing players that are extending their production capacity. Indeed, over the 3 years from 2021-2023, capacity utilization in the palm oil industry averaged just 37.1%, which is very low compared to similarly priced alternative oils such as soy (97.8% capacity utilization) and rice bran (58.2% utilization).

-

Across the industry, production costs are higher in Thailand than in the competitor nations of Indonesia and Malaysia, while Thai palm mills also operate with lower capacity utilization. This then raises their marginal costs and makes Thai products uncompetitive on global markets.

-

Non-tariff barriers stand in the way of exports. These are particularly important in the context of the environmental protection measures put in place by the EU (the bloc is one of the world’s largest markets for palm oil), a major example of which is the EU Deforestation-free Regulation (EUDR)21/. This requires that EU member states steadily reduce consumption of biofuels made from potentially carbon-intensive oil palm, with the goal that EU industries become ‘zero palm oil’ by 203022/. In addition, players will need to meet international standards by implementing the measures outlined by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO)23/.

-

Government promotion of electric vehicles (EVs) will affect demand for biofuels. In particular, the government hopes that by 2030, at least 30% of auto production will be for ZEVs (zero emission vehicles), which would then weaken consumption of biofuels.

Likely structural changes to the oil palm and palm oil industry

-

Players will focus on raising the standard of their products, for example, by improving the industry’s sustainability, manufacturing goods in accordance with the EUDR, and obtaining RSPO certification.

-

Companies will look to improve their competitiveness and cut their manufacturing costs by extending their supply chains. This could include reducing dependency on fossil fuels by manufacturing and using biodiesel or powering businesses on electricity generated from palm-processing waste products. This could also involve generating additional value from the further processing of palm husks and manufacturing sustainable aviation fuel (SAF)24/ from used cooking oil.

-

Support for the ESG (environmental, social, and governance) framework and the SDGs (sustainable development goals) will help to build trust among stakeholders in a company’s environmental stewardship and commitment to local communities. Moves in this direction may include manufacturing environmentally friendly palm oil, cutting greenhouse gas emissions, generating certified carbon credits through proactive forestry management schemes, improving energy and water management in palm mills, promoting sustainable forestry management through reforestation and biodiversity preservation schemes, and raising the quality of land use through improved cultivation and plantation management. This will then help to increase per-unit yields and reduce the need to expand plantation sizes.

Government measures/programs targeting the palm oil and oil palm industry, 2024

1) Measures covering domestic distribution include the following: (i) Businesses are required to display a sign showing the purchase price paid for palm fruits with an oil content of at least 18%, and are prohibited from advertising the price paid for fallen fruits. (ii) Manufacturers of palm oil are required to report the quantity of stocks held and their location, and to update their records at the end of each month. (iii) Businesses must obtain a permit before moving stocks of CPO weighing more than 25 kg. (iv) Palm collection yards are prohibited from engaging in any activities that might cause fruits to fall prematurely. (v) The Department of Internal Trade will install measuring devices in CPO/CPKO storage tanks when these have a capacity of at least 1,000 tonnes.

2) The Public Warehouse Organization has established two import routes: (i) customs checkpoints (for normal imports) at Map Ta Phut, Bangkok, and Laem Chabang; and (ii) checks at Bangkok for goods bound for Thailand and at Chanthaburi (for goods in transit to Cambodia), Nong Khai (for goods going on to Lao PDR) and Mae Sod (for goods to be shipped on to Myanmar).

3) Managerial measures will include the following:

3.1 The Palm Oil Management Subcommittee (appointed by the National Palm Oil Policy Committee) is chaired by the Director-General of the Department of Internal Trade and contains members representing state organizations, farmers and palm oil processors. The committee is tasked with monitoring production and industry conditions, and with determining the measures needed to maintain stability within the market.

3.2 The Provincial Palm Oil Inspection Task Force is responsible for carrying out weekly audits of palm oil stocks.

3.3 By working together, the Customs Department, the security services, and the Ministry of Commerce hope to manage imports, prevent smuggling and regulate transshipments to neighboring countries.

3.4 The Oil Palm and Palm Oil bill should soon come into force, and all relevant government bodies will join in implementing strategies to build the industry’s sustainability.

4) The government plans to add value to the oil palm and palm oil industry by targeting eight product groups, namely: (i) base oil; (ii) bio-transformer oil; (iii) environmentally friendly detergents (these are based on methyl ester sulfonate); (iv) bio-lubricants and bio-greases; (v) paraffin; (vi) pesticides and insecticides; (vii) bio-hydrogenated diesel (BHD)25/; and (viii) bio-jet fuels26/.

1/ Oleochemicals are biochemicals produced from vegetable oils and animal fats. These include fatty acids, glycerin, fatty acid esters, and fatty alcohols, and these are typically used in the food processing and consumer goods industries, where they are found in products such as cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, soap, shampoo, detergents, lubricants, and insecticides

2/ This is a precursor utilized in the production of chemicals and is often used in food processing and the manufacture of pharmaceuticals, personal healthcare products, cosmetics, and soap.

3/ Phase change materials are used to absorb and control temperatures. These are used in construction materials, textiles, goods transport, and packaging.

4/ Fatty alcohols are a type of basic oleochemical used in the manufacture of products across a range of industries including fragrancies, cosmetics, shampoo, surfactants, solvents, flavorings, detergents, lubricants, colorings and coatings, plasticizers, foam stabilizers, and additives used in the production of fibers and paper.

5/ Palm oil may be extracted either from the oil palm fruit and from the oil palm seeds, although as of the 2023/2024 season, extraction of oil from palm fruit accounted for 90.1% of global palm oil production.

6/ The oil yield per rai of various oil-producing crops is as follows: oil palm yields 500-600 liters per rai, rapeseed 100-150 liters per rai, sunflower seed 80-120 liters per rai, coconut 80-100 liters per rai, peanut 90-130 liters per rai, and soybean 50-70 liters per rai. (Note: The actual oil yield depends on the extraction efficiency of processing facilities, the quality of agricultural produce, and farm management practices.)

7/ CPO mills are generally located close to plantations since to guarantee high-quality oil, the palm fruits need to be processed within 24 hours of harvesting.

8/ Typically, harvesting can begin when oil palms are 3.5-4 years old. Yields peak when palms are 6-16 years old and then decline, although production can continue until trees are 25-28 years old. At this point, the palms are usually cut down and replaced.

9/ B5, B7, and B10 refer to mineral diesel mixed with respectively 5%, 7% and 10% biodiesel.

10/ The safety stock or buffer stock is the stock of CPO that the Public Warehouse Organization maintains in reserve in order to protect against shortages that may occur from sudden increases in consumption by downstream industrial consumers. In the event of temporary disruptions to supply, the existence of the buffer stock means that producers will be able to continue manufacturing goods that use palm oil as an input.

11/ Fresh palm fruit is a controlled commodity under the announcement of the Central Committee on the Prices of Goods and Services.

12/ The Department of Internal Trade had previously set a price ceiling of THB 42/bottle.

13/ The Prices of Goods and Services Act set a minimum price of THB 4.5/kg to be paid by mills purchasing oil palms. As per article 7, traders are also required to pay minimum prices set by the Energy Policy and Planning Office when purchasing oil palm and derivative products.

14/ As a result of palm fruits ripening externally but not internally, up to 50% of the harvest may not be suitable for further processing (source: Department of Internal Trade).

15/ India announced new tariffs on crude and refined palm, soy and sunflower oils as part of moves to support domestic growers of seed oils, especially of soy, and to protect these from prices that had fallen below the government’s minimum support price (MSP). Tax rates thus rose from 5.5% to 27.5%, while duties on refined vegetable oils went from 13.75% to 35.75%.

16/ Indonesia increased the export fees levied on CPO from USD 18/tonne to USD 33/tonne with effect from October 1st, 2024. This move was driven by: (i) the increase in the biodiesel mix from B35 to B40; (ii) the need to increase stocks in response to rising domestic demand; and (iii) the 5% fall in oil palm outputs.

17/ Near the minimum reserve level of 0.25-0.30 million tonnes.

18/ As per the announcement by the Central Committee on the Price of Goods and Services, palm fruits are a controlled product (the most recent announcement was made on June 27th, 2024).

19/ Palm trees planted in response to government incentives that ran from 2008-2012 are now 13-17 years old, and so these are within their peak producing age range of 7-16 years (source: Office of Agricultural Economics).

20/ Indonesia is supporting increased use of palm oil, for example through the development of sustainable aviation biofuels and the raising of the diesel mix from B35 to B40. This is then helping to stimulate domestic palm oil consumption and to cut energy imports. Similarly, the Malaysian authorities are also supporting an expansion in the consumption of biofuels, for example, by approving the use of B30 in trucks and heavy goods vehicles by 2030.

21/ The EU Deforestation-free Regulation (EUDR) aims to address problems with deforestation connected to seven major agricultural products and goods derived from these, namely: rubber, oil palm, beef production, cocoa, coffee, peanuts, and lumber and wooden products. The law will come into effect on December 30th, 2025, for major corporations and on June 30th, 2026, for SMEs.

22/ The EU is attempting to reduce the consumption of palm oil, and to this end, EU officials have issued the Renewable Energy Directive, Directive (EU) 2018/2001, (RED II). This specifies that the EU must achieve ‘zero palm oil’ by 2030.

23/ The Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) is an association joining farmers and producers of oil palm and palm oil products that was established in 2004 with the aim of promoting the sustainability of the industry across economic, social, and environmental fronts.

24/ These are aviation fuels made from alternative and renewable sources. These need to comply with the International Civil Aviation Organization’s (ICAO’s) Carbon Offsetting and Reduction (CORSIA) scheme.

25/ This will allow the diesel mix to return to B10 as per the Euro 5 standards and to keep any drop in consumption of CPO to no more than 0.64 million tonnes per year.

26/ Measures to manage bio-jet fuels are being developed in response to the imposition of the carbon tax on planes burning non-biofuels in EU airspace. Under the Renewable Energy Directive (REDII), the European Commission is meeting commitments made in the Paris agreement to reduce CO2 emissions by 40% by 2030. This is to be achieved by replacing these fuels with sources of clean energy by the same date, and then to achieve net zero carbon emissions by 2050.

.webp.aspx)