Where next for the Thai economy, now that inflation is rising and the recovery remains uneven?

With prices for both food and energy climbing steadily in the wake of the post-Covid surge in economic activity and, more recently, the outbreak of war in Ukraine, the specter of strengthening inflation is casting a shadow over the global economy. In the particular case of Thailand, inflation has run ahead of the central bank’s target since the start of 2022, and this is now stoking fears that rising prices will impact both household spending power and the broader economic recovery.

Krungsri Research sees inflation running north of 4% in Thailand over 2022, with price rises most notable for food, vehicles and energy. However, for Thailand, strengthening inflation should not generate the same fears as in developed countries due to greater price stickiness that is attributable to cost control measures for energy and raw material inputs, cooperation between stakeholders who are trying to hold retail prices steady, and the unwillingness of operators to regularly hike prices.

However, although this rigidity will act as a brake on inflation, this may provide only slim consolation for low-income earners, and because the latter tend to spend on a significantly different basket of goods, the impacts of inflation will likewise manifest differently. Thus, compared to high-income earners, as a proportion of their income, low-income groups spend twice as much on transport and food at home. This then means that it is possible that for poorer households, if as expected inflation hits 4.4% this year, inflation will be up to six-times worse this year compared to 2021, whereas for high-income groups, the speed of price rises will likely remain relatively sluggish.

Krungsri Research has also assessed household spending power across 2022 based on forecast real wages, and this shows that while the lowest-income earners can expect real wages to decline by -1.3% this year, the highest-income earners can look forward to a 0.7% rise in real wages. In addition, while all household income groups have seen income fall relative to the pre-Covid-19 era, this decline has been most pronounced for the poorest groups, and this reflects the inequality and unevenness of the recovery and the existence of persistent divergences in levels of household consumption.

Against this background, it is imperative that fiscal and monetary policy are used to manage inflationary pressures and to boost household incomes, with this assistance directed especially at low-income groups. Krungsri Research believes that it should be possible to manage inflationary expectations through targeted communications, while fiscal policy should be focused on increasing employment and raising industrial investment, since this will be more effective than simply hiking the minimum wage. Such a move would also help to increase real wages, reduce the divergence in the recovery as experienced by different income groups, and protect against a slowdown in the economy.

Following the reopening of economies as the Covid-19 pandemic abated, global demand for goods and services surged but supply was unable to keep up, and this has then translated into a run up in prices, the scale of which has not been seen in many decades. The situation has been dramatically intensified by the Russian invasion of Ukraine at the end of February, which has fed into a further steep rise in the price of energy and a number of other commodities, this all adding to worries over the build-up in inflationary pressures and the sustainability of the post-pandemic recovery. As elsewhere, Thailand has been hit by these problems, and the worry is that rising prices will affect incomes, spending power, and consumption levels, with a growing possibility that this will now drag on the recovery.

With inflation at its highest in more than a decade, fears are rising over the cost of living

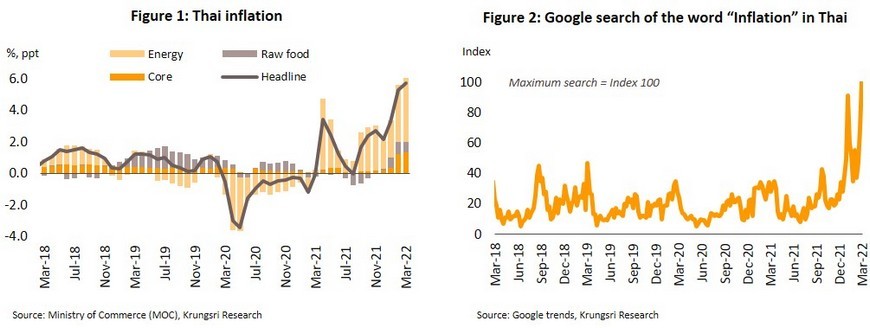

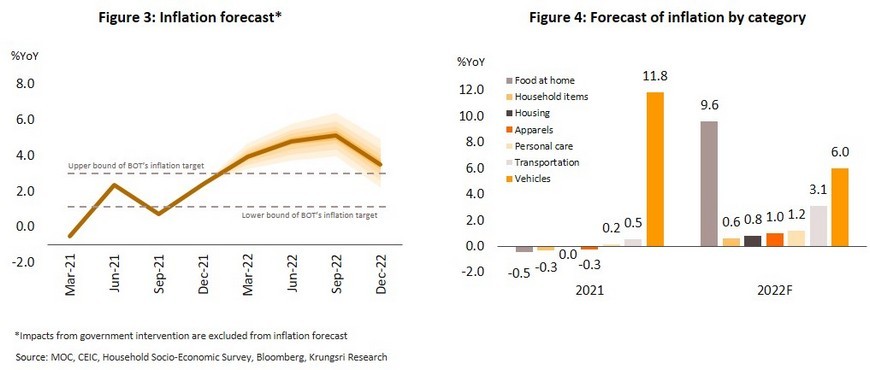

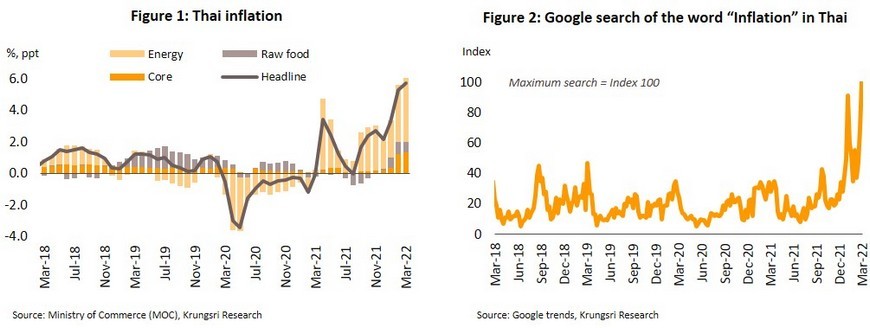

Since the end of 2021, prices for consumer goods in Thailand including petrol, cooking gas, meat, eggs, and vegetables have risen at their fastest rate in a decade, and in February, annualized inflation came to 5.73%[1] (Figure 1), significantly above the Bank of Thailand’s inflation target. Pressure on prices is most noticeable in the rising cost of energy, but although not all product groups are seeing strong inflation, the recent data have raised fears across the country of the impact of higher prices on expenditure and consumer spending power. Indeed, an indicator of the depths of these worries can be seen in the fact that the proportion of searches on Google for ‘inflation’ has now climbed to its highest since 2008 (Figure 2).

Average inflation for 2022 will likely exceed 4% in Thailand, driven most clearly by the rising cost of food, vehicles and energy

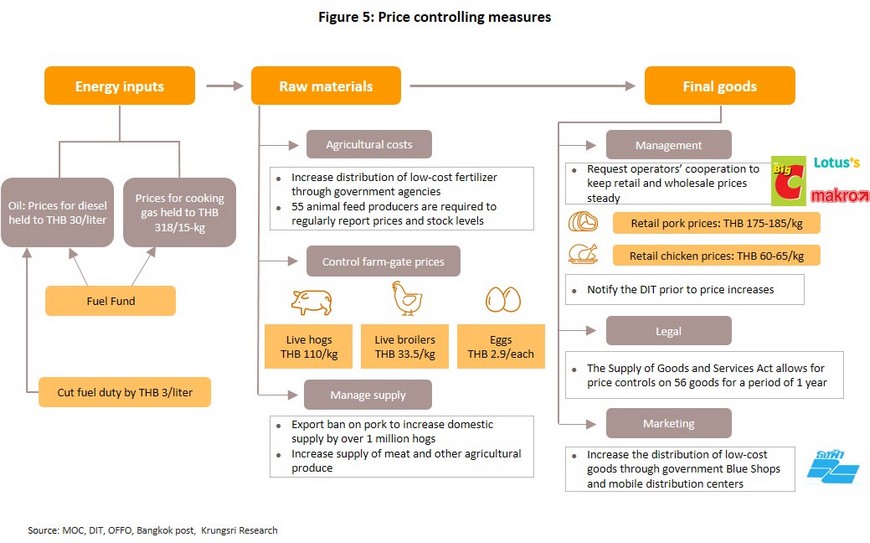

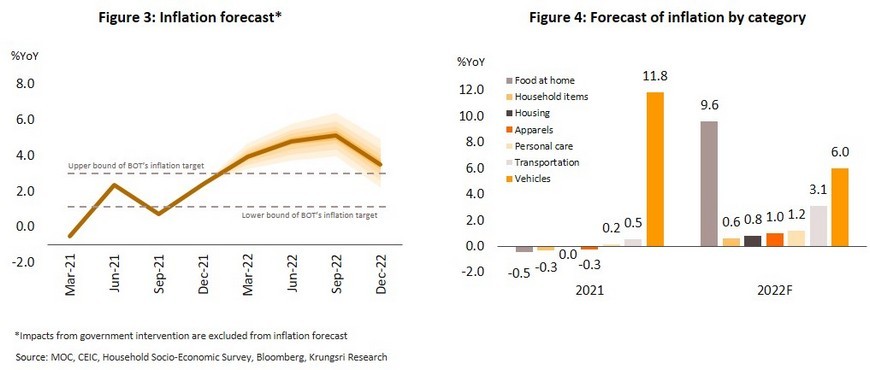

Krungsri Research has developed a model for estimating Thai inflation through 2022 that relies on a division of variables into external and internal factors. The former includes the rate of inflation in the major economies, including the US, the Eurozone, China and Japan, the price of commodities (measured via the Bloomberg Commodity Index), and the cost of diesel. Internal factors include the output gap, which reflects demand for goods on the domestic market. We now expect inflation to exceed 4% this year (Figure 3) given pressure from more expensive vehicles and higher household food bills. Inflation is also being affected by the sharp escalation in oil prices following the Russian attack on Ukraine, and across the year, crude prices are expected to stay north of USD 100/bbl, adding to manufacturing and transport costs. This will thus keep inflation above the central bank’s target band (Figure 4), and it may take until 4Q22 for inflation to begin to cool again.

Thai prices tend to be somewhat sticky thanks to price setting behavior and price controls, and this will restrict the extent to which higher costs are passed on to consumers

Prices will certainly trend upwards in Thailand but a combination of the country’s slow average rate of price increase and institutional measures to control the cost of goods will help to prevent inflation accelerating too rapidly. Research by Disyatat et al. (2018)[2] shows that the time period over which prices increase averages 6.79 months in Thailand, which is significantly slower than other developing or newly industrialized economies, such as Chile (1.6-2.5 months) or Brazil (2.14 months). The extended period of time required for price rises to take place will thus allow Thailand to avoid too sharp an increase in inflation, which will be restrained further by cost control measures, attempts to fix prices, and pricing behavior, all of which add to the country’s price stickiness.

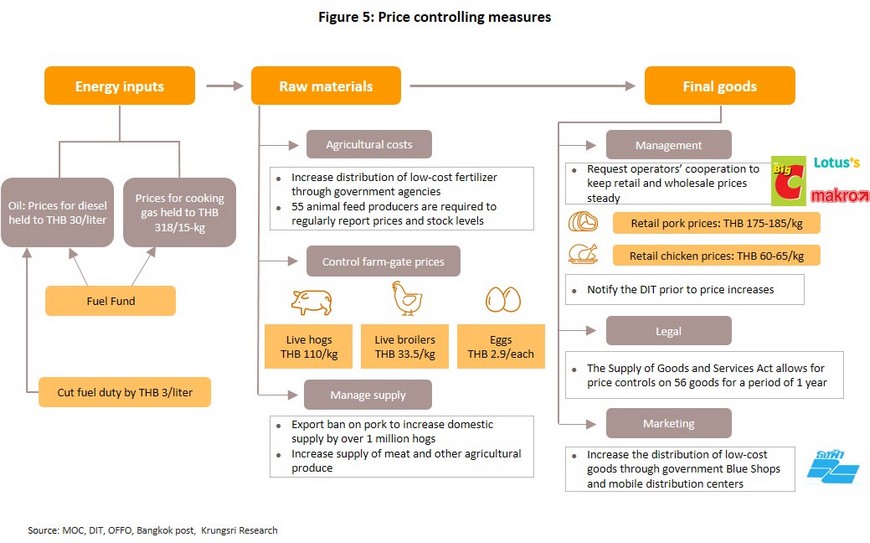

1) Cost control measures

- Fuel and natural gas are an important input into the supply of almost all goods and services and so managing the cost of these will form an important part of dealing with strengthening inflationary pressures. Thailand will be able to do this through the Fuel Fund, the operation of which helps to reduce fluctuations in oil prices and to hold back any sharp increases in pump prices. During the recent surge in energy prices, the Fuel Fund has been used to keep both manufacturing and transport costs and food costs from accelerating too steeply, which was accomplished by preventing the price of diesel and LPG from breaking above respectively THB 30/liter and THB 318/15-kilo tank. The government has also moved to cut the duty on diesel by THB 3/liter, which will again help to reduce fuel costs. These measures will therefore play an important role in preventing prices from rising excessively quickly in Thailand.

- The Ministry of Commerce is cooperating with commercial operators to manage the cost of inputs and to prevent sudden increases in the cost of items, including capital goods and especially of meat. Cooperation over the latter covers farm-gate prices together with the cost of feed, and operators are being invited to regularly report their supplies so that shortages can be avoided. 55 producers of animal feed are therefore being asked by the Ministry to report their stock levels, while players are also requested to hold the price of live hogs at or below THB 110/kilogram. This will then help to keep the price of inputs into supply chains from accelerating too rapidly

2) Price controls are used to set the retail price of goods, which mark the final point at which inflation may be passed on to consumers. At present, the Department of Internal Trade is charged with overseeing the sale price of over 200 goods and services, these generally being basic consumer goods such as pork, chicken, palm, oil, corn, etc. The DIT tracks and manages the prices of these goods to ensure that fluctuations in these does not excessively impact the overall cost of living, and to this end, if prices escalate rapidly, the Department may adjust these accordingly. At the same time, to help reduce consumer costs, the authorities are also increasing access to distribution channels through which discounted goods are sold. Retail price controls are thus a means by which price stickiness is maintained (Figure 5).

3) Price setting behavior is revealed by a survey distributed to companies by the Bank of Thailand in February 2022. This showed that at that time, over half of all companies that responded did not intend to pass on higher costs to consumers. Two principal reasons were given for this: the extent of market competition and consumers’ weak purchasing power. Companies were thus unwilling to raise prices as a way of passing on higher costs to household consumers, and this is another factor maintaining price stickiness.

In addition, the regularity with which changes are made to the weightings in the basket of goods used to assess inflation will also affect the inflation data. Normally, these are revised every 4-5 years in Thailand, which differs from the practice elsewhere. For example, in the Eurozone in countries such as Spain and Germany, changes are made annually, while in the US, these are revised every 2 years. By comparison, the much less frequent revision of the Thai data means that the figures on prices and inflation may not fully reflect consumer behavior and expenditure or the actual prices borne by Thai consumers.

Prices may not surge rapidly in Thailand as they have done in countries including the US, the UK and the Eurozone, but domestic inflation is still affecting Thai households’ spending power and their cost of living. However, how this plays out in practice will vary depending on income and consumption patterns, and as has been shown to be the case repeatedly in past economic crises, low-income groups’ limited access to financial buffers places them in a more exposed position, such that following the crisis, recovery for these groups is likely to be more difficult and more protracted than for higher-income groups.

Different experiences of inflation

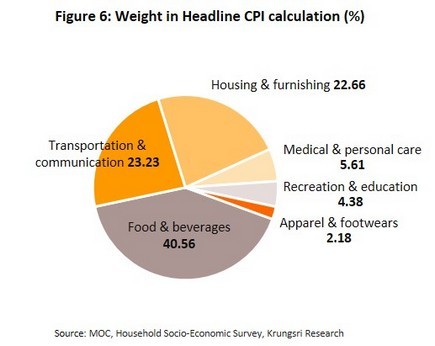

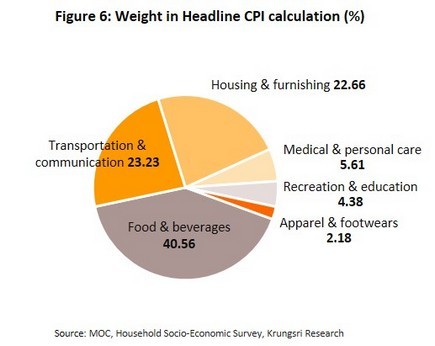

Looking at the figures for headline inflation and the weightings of expenditure used to calculate this shows that the single largest area of expense is food and non-alcoholic drinks, which accounts for 40.6% of the value of the basket of goods used to calculate inflation. This is then followed by transport and communication (23.2%) and accommodation (22.7%) (Figure 6), but because the actual expenditure of particular income groups varies from one group to the next, a fact these weightings do not accurately reflect, the headline inflation figures may be somewhat misleading.

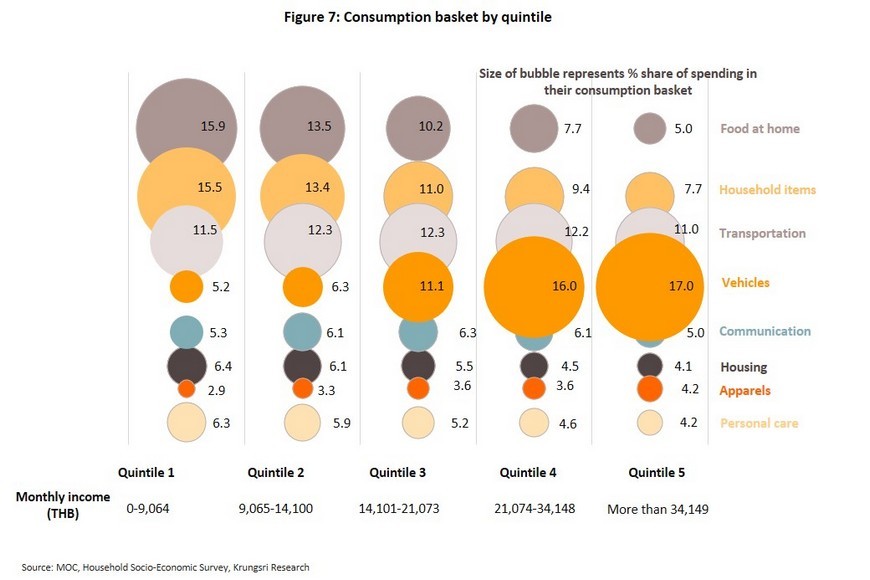

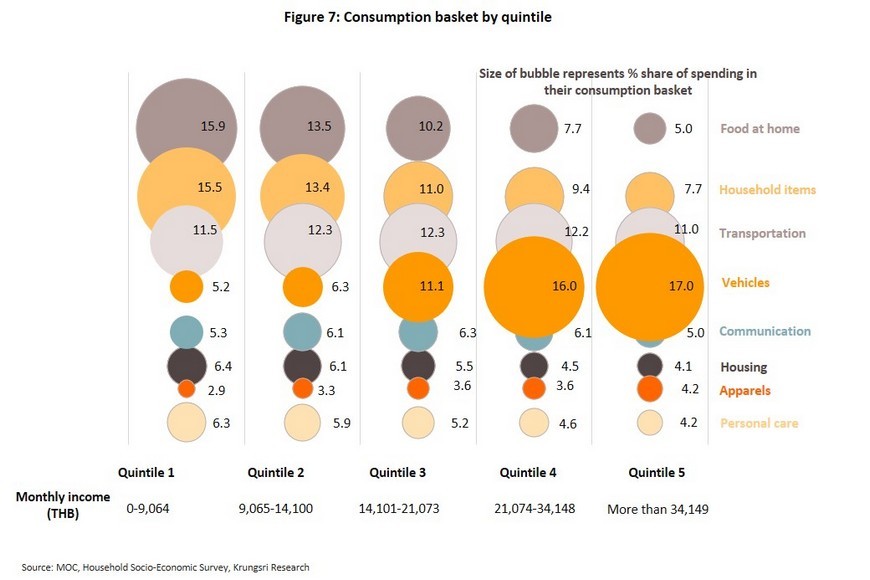

To better understand this situation and to better analyze the impact of inflation on different income groups, Krungsri Research has split Thai consumers into 5 categories according to their monthly household income, with each group’s consumption represented by a different typical basket of goods. This then shows that mid- to low-income earners spend a higher proportion of their income on food at home than do high-income earners. Thus, the poorest households (with an income under THB 9,064/month) spend the greatest share of their income on food at home (15.9% of all expenditure). This was followed by household items (15.5%) and transportation (11.5%). By contrast, for the richest households (those with an income over THB 34,149/month) food at home accounted for just 5.0% of expenditure, while this group’s biggest expenses were on vehicles (17.0%) and transportation (11.0%) (Figure 7).

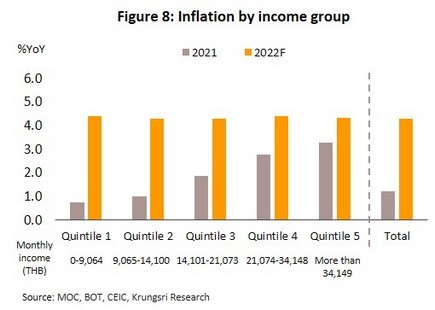

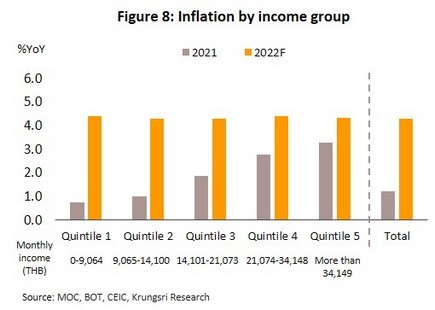

The combination of the different consumption patterns and the rising cost of food and energy means that the impacts of inflation will differ from one household to the next. Krungsri Research estimates that for the lowest-income group, inflation will come to 4.4% in 2022 compared to just 0.7% in 2021, meaning that in 2022, low-income households will face price rises that are over 6-times as steep as they were a year earlier. By contrast, for high-income earners, inflation should run to 4.3% in 2022 against 3.3% a year earlier (Figure 8) and so although all households will have to deal with the effect of higher headline inflation on income and expenditure, the overall impact of which will be roughly similar for these two groups, low-income groups will see a much faster and harder jump in prices this year.

Declining real wages for low-income households will exacerbate differences in spending power

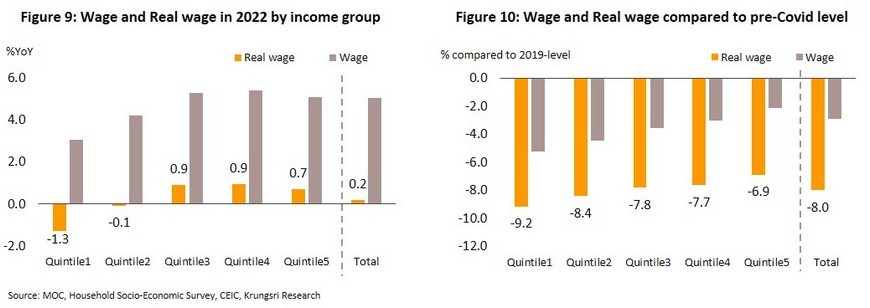

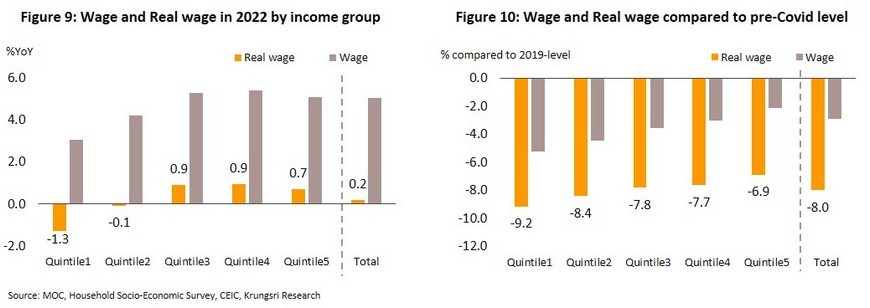

Rising inflation will also undercut household purchasing power, and although wages are rising with the economic rebound and stronger demand for labor, Krungsri Research has analyzed changes to real wages[3], and for the two lowest-income groups, this is expected to fall by respectively -1.3% and -0.1%. In contrast, for the highest-income group, real wages are forecast to increase by 0.7% relative to 2021 (Figure 9), a difference that highlights the fact that purchasing power is recovering at significantly different rates among different income groups.

In addition, comparing wages pre- and post-Covid-19 shows clearly that across all income groups, wages have dropped substantially, though again, it is the lowest-income households that have seen the greatest relative drop in wages across the pandemic (Figure 10). Unfortunately, this then exacerbates the economic precarity of low-income households even further compared to richer groups.

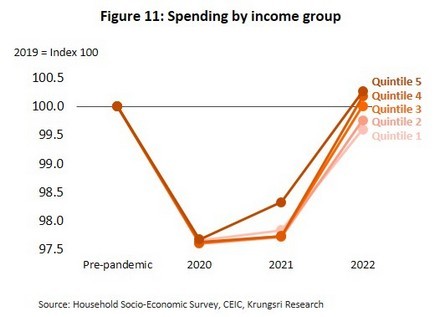

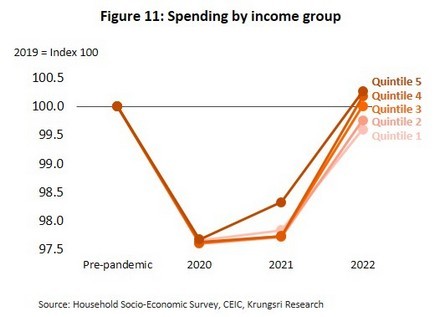

Differences in the negative impacts of economic turbulence on Thai households are not limited to just inflation and income, but also extend to include differences in consumption, and the uneven speed of the recovery is another factor that may drag on Thailand’s economic rebound. Thus, households in the mid- to upper-income groups can expect their expenditure levels to recover somewhat rapidly, and for these groups, consumption is likely to return to its pre-pandemic level during 2022. However, for the poorest 40% of households, recovery in consumption is going to be delayed even further (Figure 11).

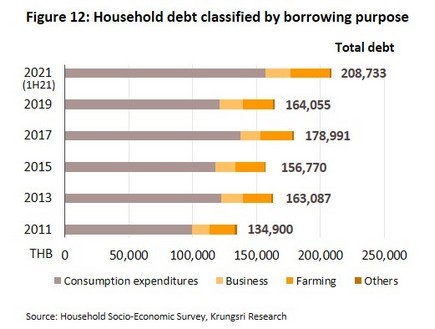

In addition to the uneven recovery in consumption, rising household debt may also become another factor that weighs on growth. Krungsri Research has analyzed data on debt levels from the first half of 2021 and this shows that on average, debt has increased by over THB 200,000 per household, most of which has been used for consumption (Figure 12). In light of this, rising household incomes in 2022 may not translate fully into greater consumption since at least some of this income will be used to pay down these debts. Alternatively, if households wish to maintain their current level of consumption, they will need to take on even more debt, and this exposure to risk may lead to further divergence in the rate of economic recovery among different income groups.

Although the risk environment is worsening, picking out the correct policy may provide a safe way forward

In the view of Krungsri Research, the main problem confronting the Thai economy is the negative impact of strengthening inflation and weakening incomes on consumer purchasing power. However, these problems can be addressed by a mixture of monetary policy that aims to manage inflationary expectations and fiscal policy that is targeted at alleviating the effects of economic weakness on low-income households. Such a move would then form an important bulwark protecting against an economic slowdown.

In terms of monetary policy, central banks worldwide are in the process of weighing the possibility of raising policy rates as they try to manage inflationary pressures and to prevent these from undermining growth. However, in the case of Thailand, the recovery remains uncertain and fragile, and because higher rates would add to the costs of borrowing and increase monthly interest payments for indebted households, which would then adversely affect the financial standing of poorer families even more, there is only a limited space within which rates might be raised. Instead, policymakers should focus on managing communications to anchor inflationary expectations since in the view of central banks, these are an important factor affecting price rises. Indeed, research by Ariyavutikul et al. (2019)[4] shows that successfully managing the tone of communications regarding monetary policy by the central bank would help to better anchor the public’s expectations of inflation and that the effects of this would be most clearly seen within one quarter of these communications being made.

With regard to fiscal policy, Krungsri Research has used a Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) model to assess possible responses to the current environment. This looks at the possibility of targeting assistance at low-income and unskilled labor so that their real wages rise, the differences between the purchasing power of different income groups are reduced, and the economy benefits from rising consumption. Measures that might be implemented in pursuit of these goals include increasing the minimum wage, raising employment levels, and stimulating additional investment in industry.

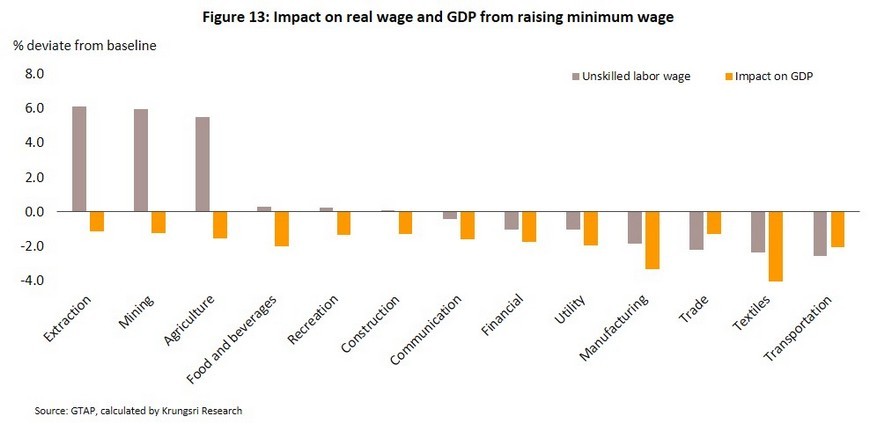

Increasing the minimum wage would directly help to boost income for Thai households by raising the wages for low-income and unskilled workers. At the same time, this would add to the bargaining power of workers already benefitting from higher incomes, and these individuals would then be better able to negotiate wage rises.

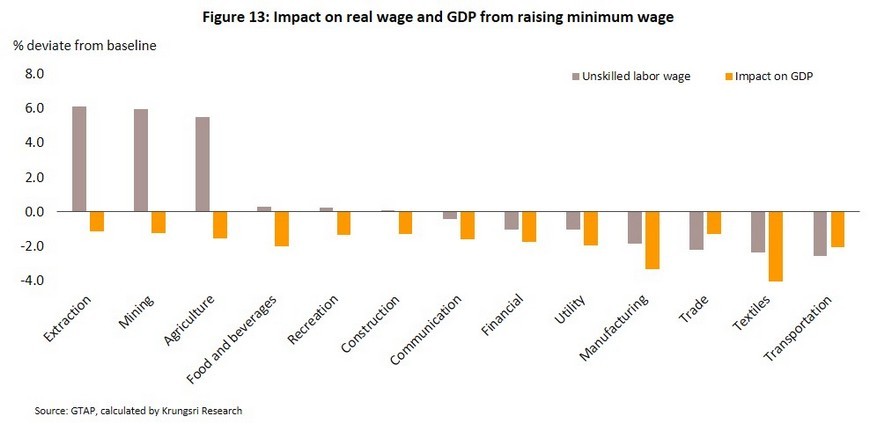

Analysis shows that a 10% rise in the minimum wage would increase real wages in a number of different industries. This effect would be strongest in the oil and gas extraction industry, where real wages would rise 6.1%, followed in order of the effect size by mining, agriculture, food and beverages, tourism, and construction. However, in some labor-intensive industries (e.g., transport, textiles, and trade), the rise in labor expenses would mean that the net effect may be negative, and because of this, the overall impact of a hike in the minimum wage would be to reduce total output and to cut Thailand’s GDP growth to 2.4%. One explanation of this net negative impact is that wage growth would likely outpace increases in labor productivity and many companies would have difficulty managing the sudden jump in overheads that the wage rise would entail. Beyond this, a 10% increase in the minimum wage would also add 0.5% to Thailand’s rate of inflation.

Although raising the minimum wage would increase real wages, there would be a gap between the two, while a second gap might emerge between higher wages and stagnant productivity that would then tend to have the net effect of adding to businesses’ expenses, rather than increasing overall economic output. In addition, the boost to prices that a wage rise would give would also worsen Thai household’s current problems with inflation and add to the divergence in recovery paths that different income-groups are seeing.

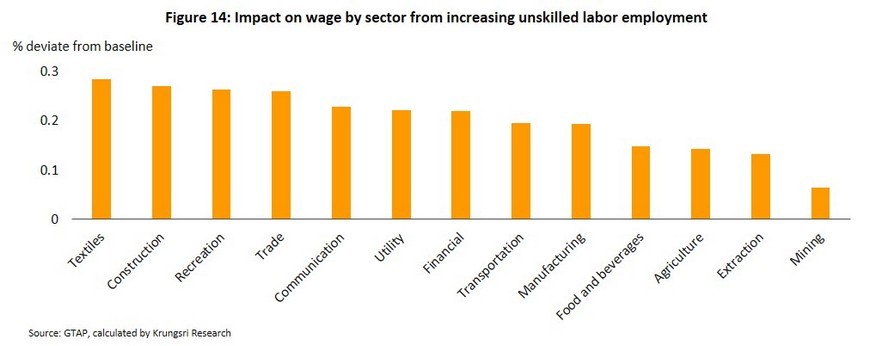

- Increasing overall levels of employment

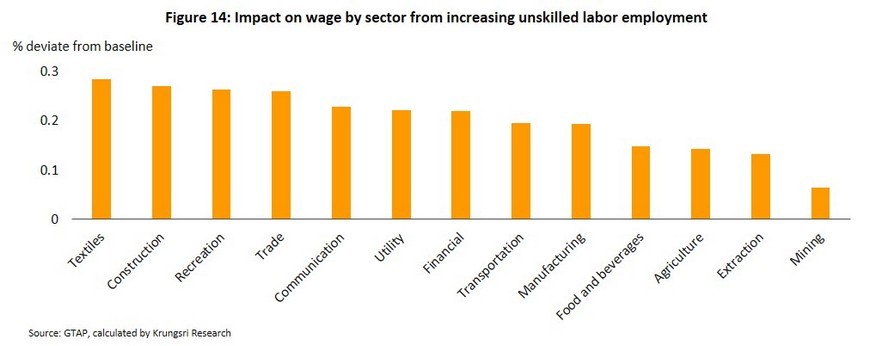

Increasing total employment is another direct means by which incomes can be raised and household spending power boosted, which would then help to pave the way to a stronger recovery in consumption. Analysis by Krungsri Research shows that because these are labor-intensive areas of the economy, in Thailand, a 1% rise in employment levels among unskilled labor would translate into a 0.28% increase in wages in the textile industry, a 0.27% increase in wages in construction, and a 0.26% increase in wages in the tourism sector. Plus, raising overall employment would also add 0.2% to GDP.

Although increasing employment may not raise incomes as dramatically as a hike in the minimum wage, expanding employment rolls, or encouraging companies to do this, would help to offset declining wages and potentially increase overall consumption. Such a policy may also have positive long-term effects since if unskilled workers have the opportunity to participate more fully in labor markets, when the economy fully recovers from the Covid-19 pandemic, these workers would constitute an important part of the labor force that would already be in place ready to meet additional demand for goods and services. This would thus help to sustain growth over a more extended timeframe.

- Encouraging additional investment in industry

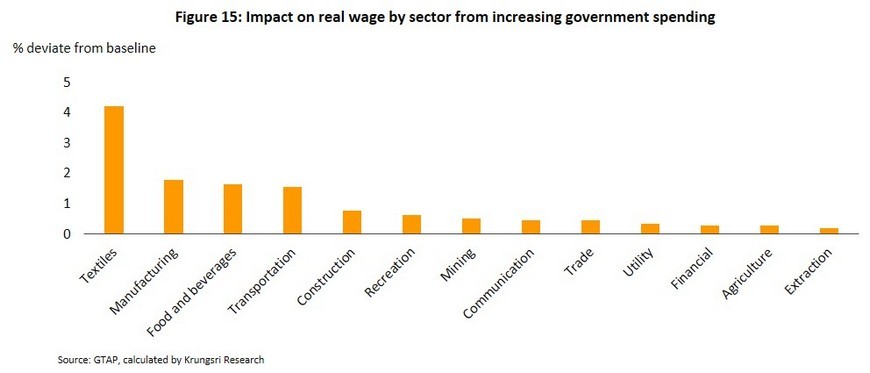

To investigate the effects on the Thai economy of a policy that aimed to stimulate private-sector spending in different parts of the economy, Krungsri Research has also looked at the effects of a tax cut in various industries.

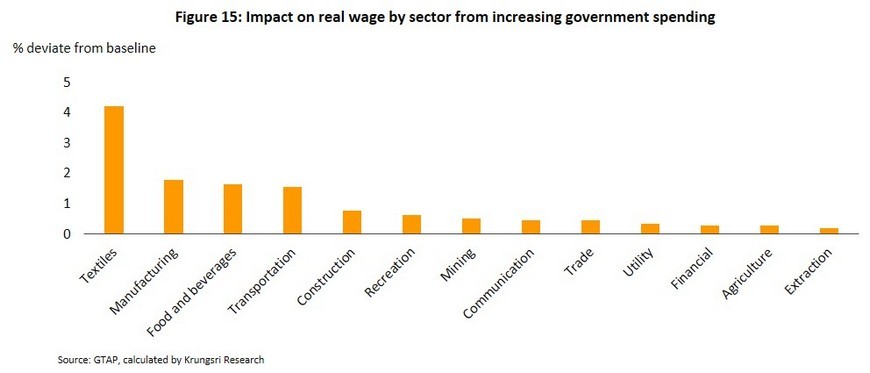

The results of this research show that if the government is successful in raising levels of private-sector industrial investment by 10%, incomes for workers in those industries will increase, though at varying rates. The effect will be strongest in the textile, manufacturing, and food and beverages, where income will strengthen by respectively 4.2%, 1.8% and 1.6%. Meanwhile, the effect on the Thai economy overall will be to add 0.4% to GDP from manufacturing industry, because it is more dependent on both machinery and labor than other industries, compared to 0.02% of GDP from the transport industry, and 0.01% from food and beverages. However, investment in other industries may have a negative impact on GDP growth, possibly because of increased competition over resources.

Given this, if policymakers wish to raise workers’ wages without precipitating excessive impacts on growth, developing mechanisms that stimulate greater private-sector investment, especially in manufacturing industries (e.g., by providing for increased tax breaks), would be the most effective route to take. This would then increase employment, the impacts of which would be amplified by the multiplier effect.

Given the range of policy options outlined above, Krungsri Research believes that the most effective option would be to encourage greater investment in manufacturing and to increase employment levels, since these would help low-income and unskilled workers enter the labor market and so compensate for lower household incomes. By contrast, raising the minimum wage has the disadvantage of opening up a gap between the nominal increase in wages and the actual increase in real income, though at the same time, this saddles business owners with higher costs and runs the risk of further adding to current inflationary pressures, with all the negative consequences for the economy that that would entail.

In conclusion, the recent spike in prices for food, vehicles, and energy has combined with variation in the consumption patterns of different income groups to throw additional light on the unevenness of the recovery in incomes and consumption. Moreover, because of differences in the latter, relative to wealthier households, low-income households are likely to experience a much faster rate of increase in inflation this year, and this will eat into income and undermine consumption. Government measures are therefore desperately needed to compensate for the negative impacts on household budgets and to sustain the overall recovery, and from the policy options discussed above, Krungsri Research believes that the most effective and hence most preferred option should be to increase employment and to encourage greater private-sector investment in manufacturing. These are in contrast to raising the minimum wage, which would likely result in an underwhelming increase in real wages while also feeding stronger inflation, the upshot of which would be to potentially worsen the financial position of some Thai households, even as the economy recovers.

[1] Bank of Thailand’s headline inflation target is 1-3%

[2] Disyatat, P., Apaitan, T., & Manopimoke, P. (2018). From markets to supermarkets: 5 facts about Thai prices (aBRIDGEd No. 7/2018). Puey Ungphakorn Institute for Economic Research. https://www.pier.or.th/abridged/2018/07/

[3] The real wage is the inflation-adjusted value of earnings

[4] Ariyavutikul, M., Throngnumchai, K., Phongpiyaphaiboon, N., & Chucherd, T. (2020). The effectiveness of fiscal policy communications in Thailand (aBRIDGEd No. 20/2020). Puey Ungphakorn Institute for Economic Research. https://www.pier.or.th/abridged/2020/20/