EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The hotel industry will continue to see improving conditions over 2024 to 2026, helped by ongoing government support for the industry and the annual foreign arrivals returning close to their pre-pandemic level of 38-40 million by 2025. Meanwhile, domestic tourists are also expected to be making 200 million trips annually by 2025. To counter labor shortages in some parts of the market and to respond to changing demand from digital consumers, large operators will step up their investments in both technologically driven service provision and in green or environmentally friendly hotels, with expansion in supply being strongest in the major tourist areas. Overall, the national occupancy rate is forecast to remain above 70% in 2024.

Nevertheless, the rebound in foreign arrivals and growth in demand may fall short of expectations. One cause of this may be ongoing geopolitical conflicts. For example, if fighting between Israel and Hamas in the Gaza Strip drags on, this may push up the price of crude. This would then add to transportation costs, impact the global economy, and drag on growth in the foreign tourist market. In addition, growth in the Chinese market may underperform if the economy remains lackluster since in this case, Chinese tourists will likely continue to favor domestic travel.

Krungsri Research view

-

Hotels in the major tourist areas of Bangkok, Pattaya and Phuket: Income growth will track the rapid recovery in foreign tourist arrivals. The occupancy rate should average around 80% from 2024.

-

Hotels in regional centers and in other important tourist areas1/: These hotels will see revenue benefits from ongoing recovery in domestic tourism and government measures to stimulate the tourism sector.

-

Hotels in other provinces: Because travelers in these provinces are often on their way to provincial centers or tourism sites elsewhere, income for players in this group will remain broadly flat. Occupancy rates will tend to lag the other two main market segments.

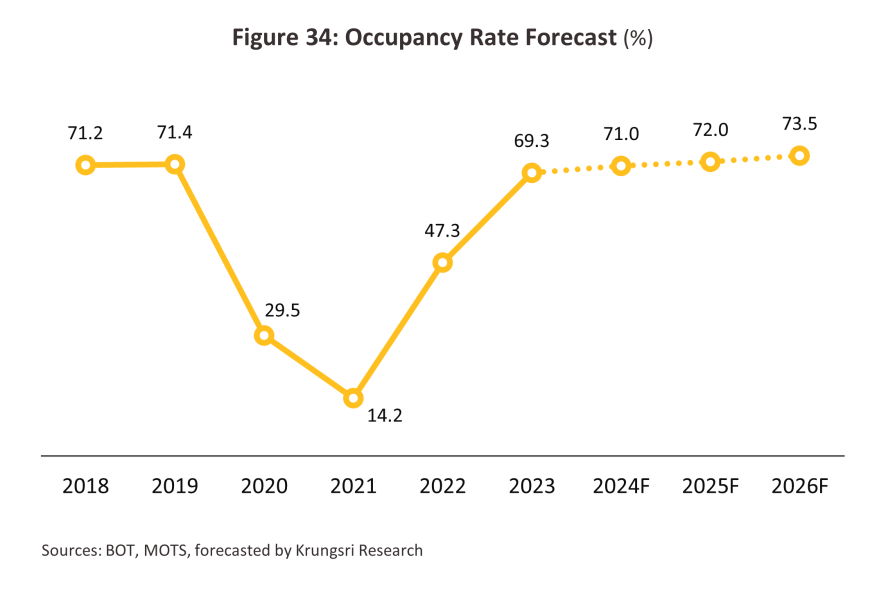

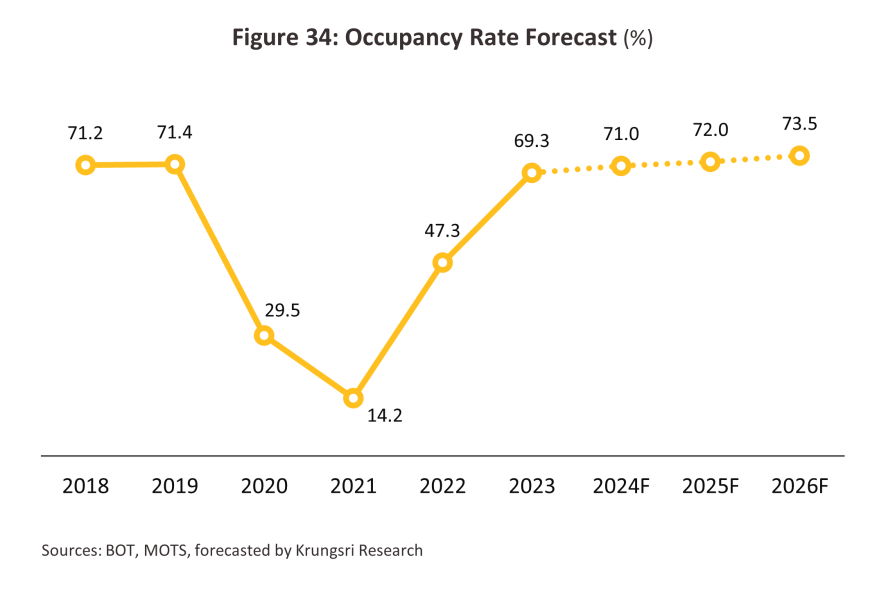

Across the industry, competition remains intense from the strength of the supply coming from both hotels and alternative forms of short-term accommodation. This, coupled with only slowly growing demand, will hold the average national occupancy rate to a forecast 71.0%, 72.0% and 73.5% in each of 2024, 2025 and 2026, slightly outperforming the 2019 pre-pandemic average of 71.4%.

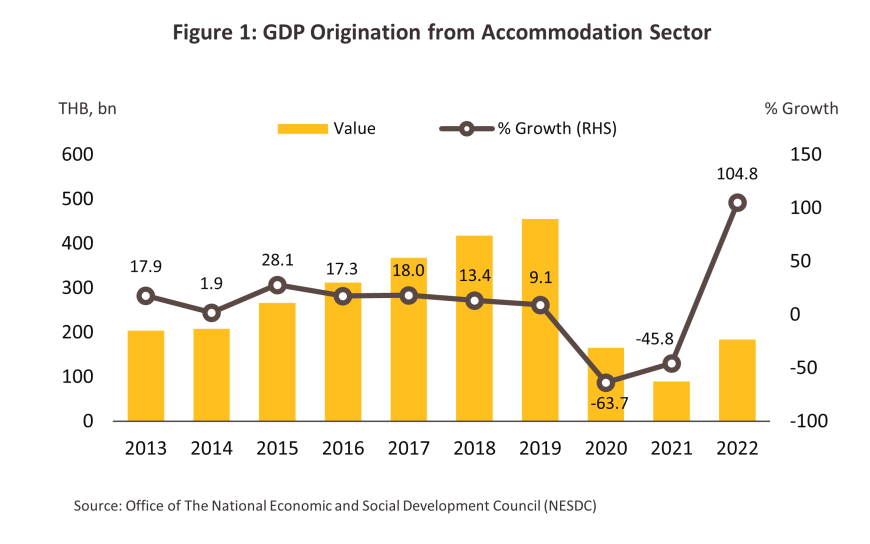

Overview

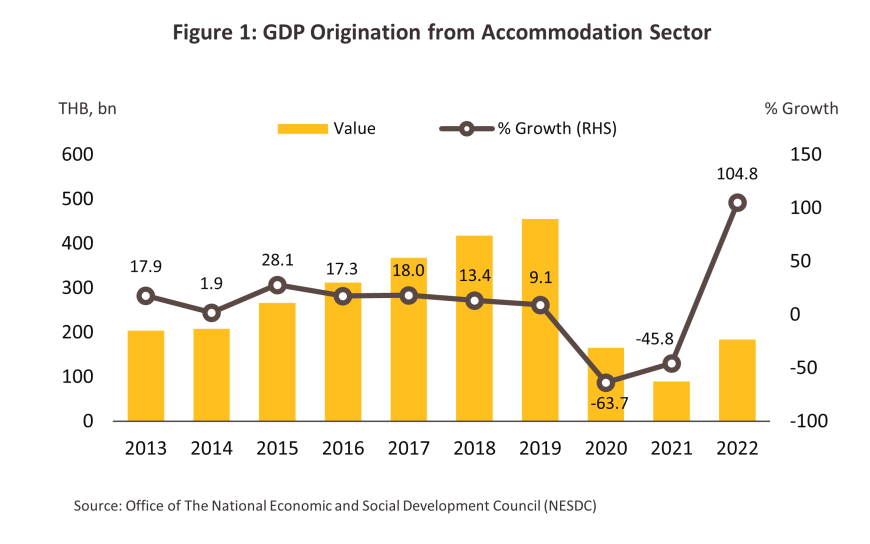

The hotel trade (which here covers hotels, resorts and guesthouses) is directly connected to the wider tourism sector, of which it forms an important part. In terms of its contribution to the broader economy, over 2017-2019, short-term accommodation services accounted for 2.5% of Thai gross domestic product (GDP), but the outbreak of COVID-19 delivered a severe body blow to the industry and its contribution to GDP slumped to 1.0% of the total in 2020 and then to just 0.6% in 2021. However, the easing of the pandemic in 2022 set the industry on the road to recovery, and with both Thailand and originating countries relaxing pandemic controls, the tourism industry began to revive (Figure 1). Naturally, hotel operators’ turnover comes mainly from room charges, and these account for approximately 65-70% of all hotel income. A further 25% comes from sales of food and drink, though the percentage varies with the type of hotel, and four- and five-star hotels will typically derive a greater portion of their income from food and drink than will smaller hotels. Income from other sources, such as providing washing and ironing services and collecting rents from shops operating on hotel premises, will usually contribute an additional 5-10% to total receipts.

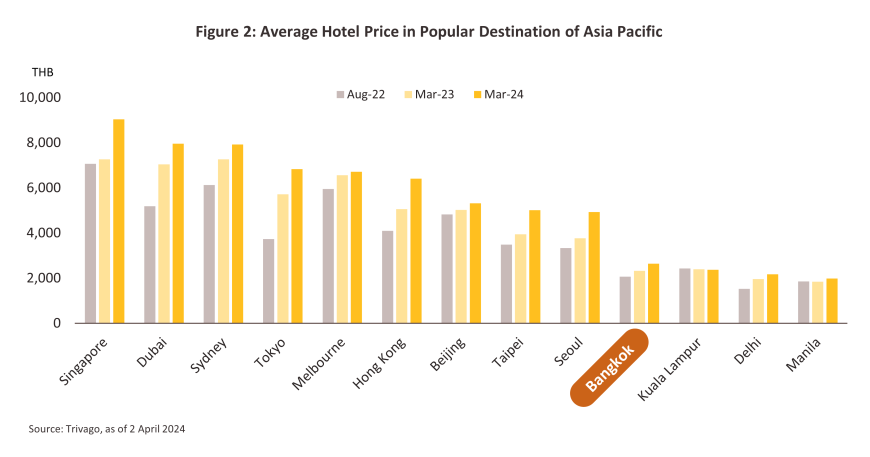

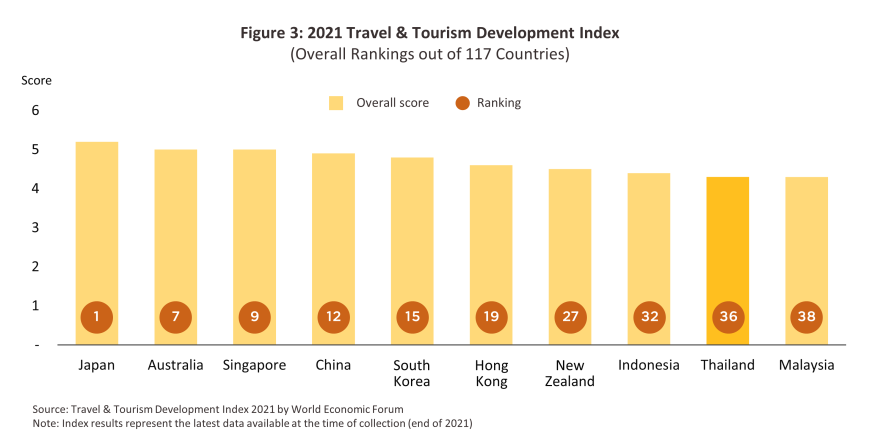

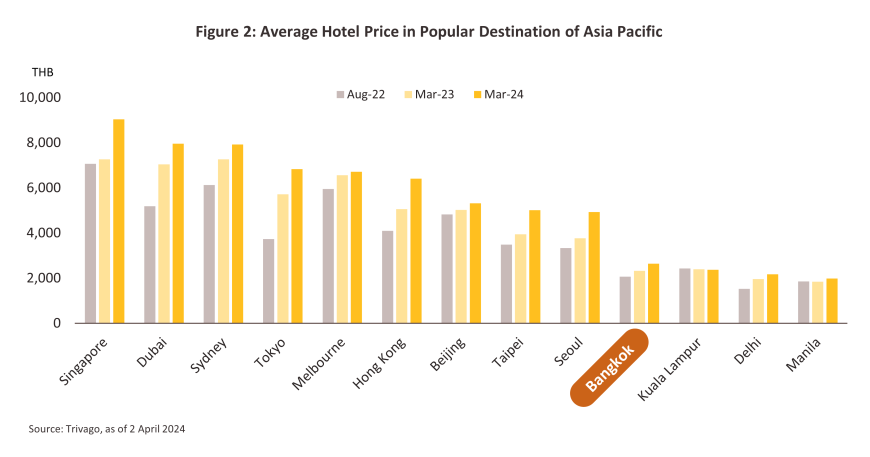

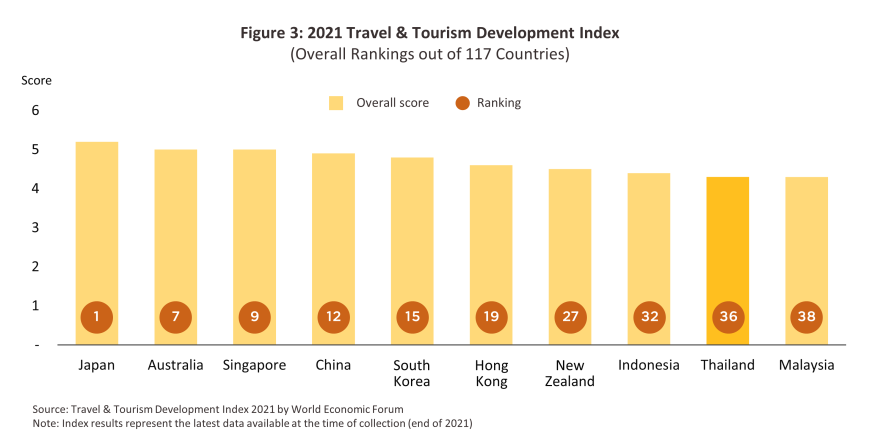

Thailand is regarded as one of the world’s foremost tourist destinations, and the country’s continuing ability to attract foreign arrivals is explained by: (i) the world-class tourism attractions that are spread throughout the country, in particular in the major destinations of Bangkok, Pattaya, and Phuket; (ii) the competitive pricing of its accommodation and the low cost of living relative to competitors elsewhere in the Asia-Pacific region (Figure 2), which provides tourists with considerable value for money compared to other countries; (iii) the country’s extensive, comprehensive and constantly upgraded communications networks and national infrastructure; and (iv) the rising number of low-cost carriers serving the local market. These factors have helped to give Thailand an edge over its competitors. Indeed, the 2021 Travel and Tourism Development Index, compiled by the World Economic Forum and published in May 2022 (the most recent available), places Thailand 36th out of the 117 countries surveyed, 9th in the Asia-Pacific region, and 3rd in Southeast Asia, where it sits behind just Singapore and Indonesia (Figure 3). In the Travel and Tourism rankings, Thailand scores particularly highly relative to other countries in the Asia-Pacific region with regard to its price competitiveness and tourist service infrastructure, and comes after only Singapore and Indonesia on safety and security.

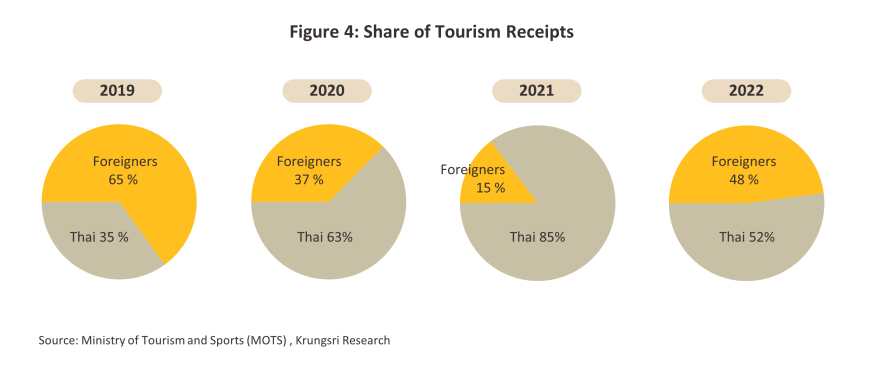

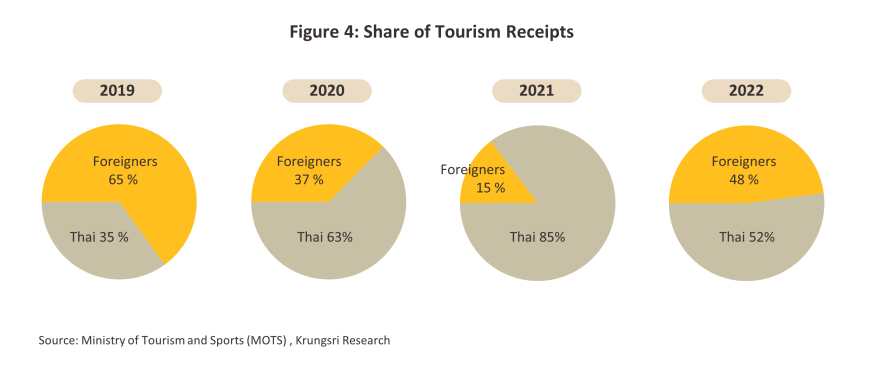

In normal circumstances, the tourism sector is a major driver of the Thai economy, though because their hotel stays are longer and they tend to spend more per head, the market is tilted in favor of foreign arrivals, and so in 2019, these accounted for 65% of total income to the industry. By originating area, the most important market is East Asia (i.e., China, Japan, South Korea, Hong Kong, and Taiwan), which contributes 42% of all overseas arrivals and 41% of spending by foreign tourists. However, the extended COVID-19 pandemic meant that over 2020 and 2021, the number of tourists visiting Thailand crashed and in 2020, income from this segment slumped to 37% of all receipts from tourism in that year and then to just 15% in 2021. In 2022, the easing of the pandemic allowed countries to begin relaxing travel restrictions and with recovery in overseas arrivals beginning to gather pace, their contribution to income bounced back to 48% of the total (Figure 4).

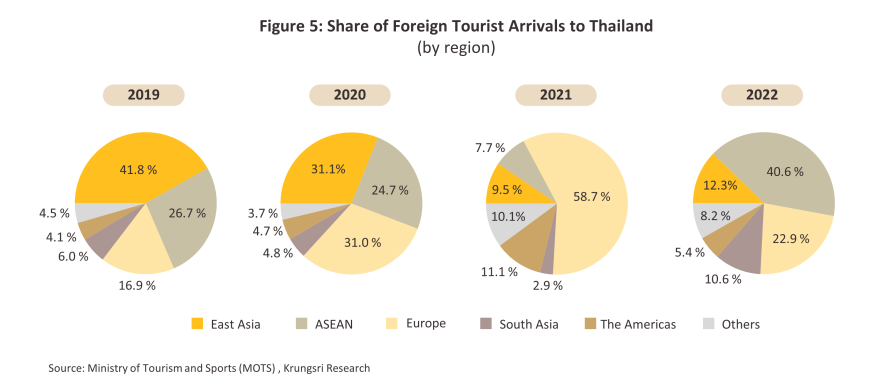

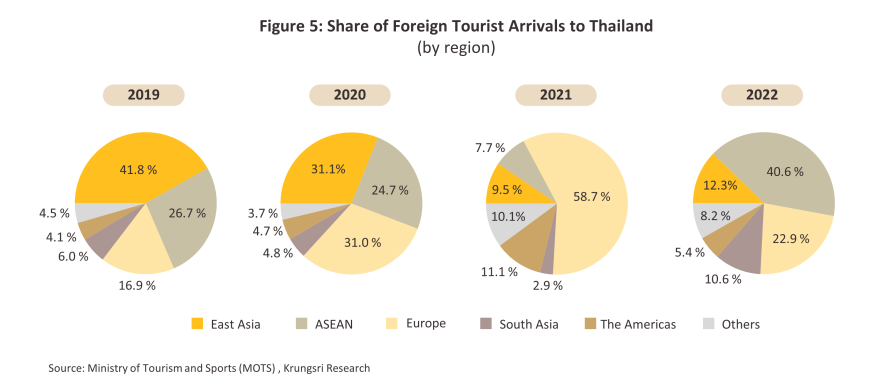

In 2019, prior to the outbreak of COVID-19, the most important markets were East Asia, the source of 42% of all arrivals, the ASEAN region (with 27% of the total), and Europe (17%), but the pandemic caused a major shift in the market, and over 2021-2022, the share of East Asian tourists fell to 31% and then 9% of the total. At the same time, the contribution of European tourists to the overall market rose to 31% and then 59% (Figure 5). This was a result of: (i) China’s extended zero-COVID policy and the country’s block on outbound tourism; and (ii) compared to arrivals from other areas, the greater sensitivity of East Asian travelers to issues connected to safety (e.g., the risk of infection, civil disturbance or violence in destination countries).

Prior to the pandemic, the most important individual markets for the Thai tourism sector were China, Malaysia, India and Russia, which combined accounted for 47.2% of all foreign arrivals. The situation for these is described below.

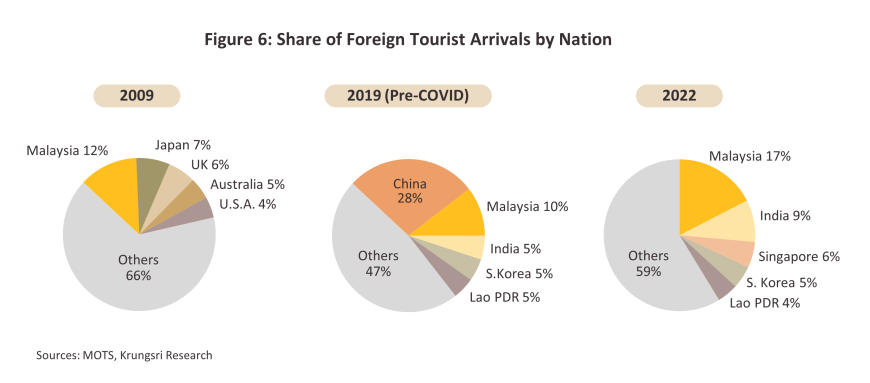

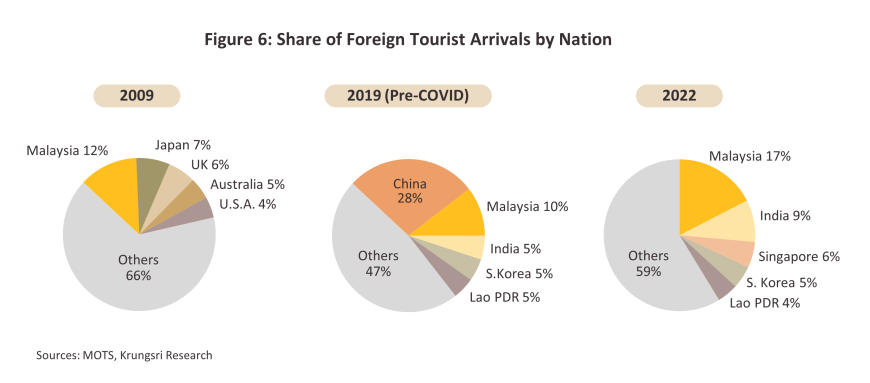

China: With 11 million Chinese tourists coming to Thailand in 2019 (28% of all foreign arrivals, up from just 5% in 2009) and income from these totaling THB 540 billion, China was by some margin Thailand’s most important market for tourism (Figure 6). A number of factors combined to encourage Chinese visitors to come to Thailand in ever greater numbers, including: (i) the relaxation of regulations from the Chinese government on outbound tourism2/; (ii) the expansion in the Chinese ‘upper middle’ and ‘mass middle’ classes from 68% of urban households in 2012 to 76% in 2022 (source: McKinsey & Company, China Briefing); (iii) the increasing number of low-cost carriers and direct flights linking Thailand and China; and (iv) Thai government policies to promote tourism, including the waiving of fees for visas issued on arrival (VOAs). As such, the Chinese segment rapidly expanded to become the most important section of the market for foreign hotel guests, though its influence has tended to be concentrated in the main areas of Bangkok, Pattaya, and Phuket.

Malaysia: Malaysia had been Thailand’s second most important tourist market pre-Covid, and in 2019, income from the 4.3 million Malaysian tourists (10.5% of all arrivals) totaled THB 110 billion, compared to the THB 140 billion coming from all CLMV tourists combined. Indeed, until it was overtaken in importance by China in 2012, Malaysia had been Thailand’s most important tourism market. Tourism from Malaysia has been helped by the strength of cross-border Thai-Malaysian trade and the opening of travel lines connecting the two countries (e.g., the Kuala Lumpur-Chiang Mai air route).

India: With 2.0 million arrivals (or a 5.0% share), India was Thailand’s 3rd biggest market for tourism in 2019. Before the pandemic, this segment had been growing strongly and for the five years from 2015 to 2019, the Indian market sustained double-digit growth, leading to annual receipts of THB 86 billion in 2019. This growth has been supported by several factors. (i) India’s economy has been performing well, and with this the middle class is expanding; the People Research on India’s Consumer Economy (PRICE) estimates that in 2030-2031, 715 million Indians will qualify as middle class, up from 432 million in 2020-2021, with this due to accelerate to 1.02 billion by 2046-2047. (ii) Growth in the market has been helped by the expansion in services provided by low-cost carriers, and flying between Thailand and Indian cities including Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai, and Bangalore takes just 4-5 hours. (iii) Indians have a preference for holding marriage ceremonies in Thailand due to its cheaper accommodation and overall lower costs compared to India or elsewhere.

Russia: The Russian market generated THB 100 billion in income and accounted for 3.7% of all foreign arrivals in 2019, making it the most important component of the European segment. Thanks to a combination of factors, the Russian market has shown sustained growth. (i) Unrest in the Middle East had the effect of encouraging Russian tourists to switch from travel destinations such as Turkey, Egypt and the UAE that had previously been popular to travelling to Thailand instead. This was especially the case between 2010 and 2013, when the number of Russian arrivals jumped by an average of 46.1% per year, compared to annual growth of 22.5% between 2006 and 2009. (ii) The Thai government has promoted Thailand as a tourist destination to Russians by signing an agreement with the Russian government to allow visa-free tourism between the two countries for periods of up to 30 days (with effect from April 2007 onwards) and by putting on TAT roadshows in Russia. (iii) The number of direct and charter flights between Russia and Thailand increased.

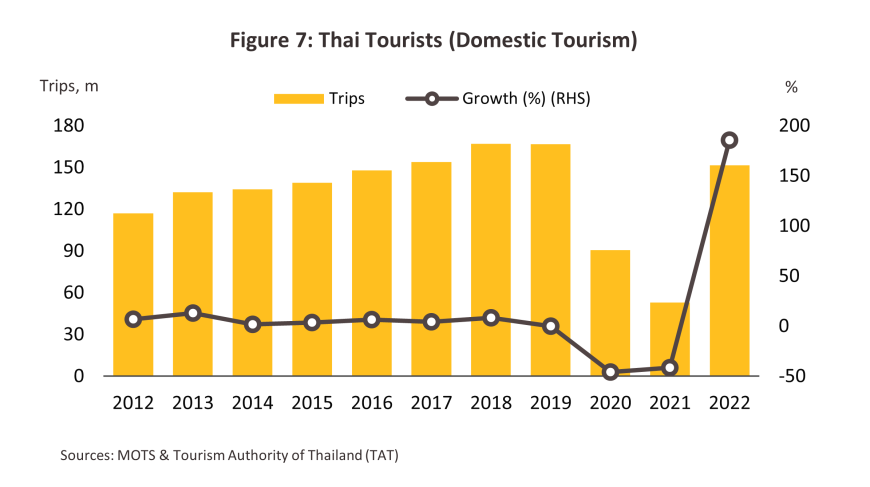

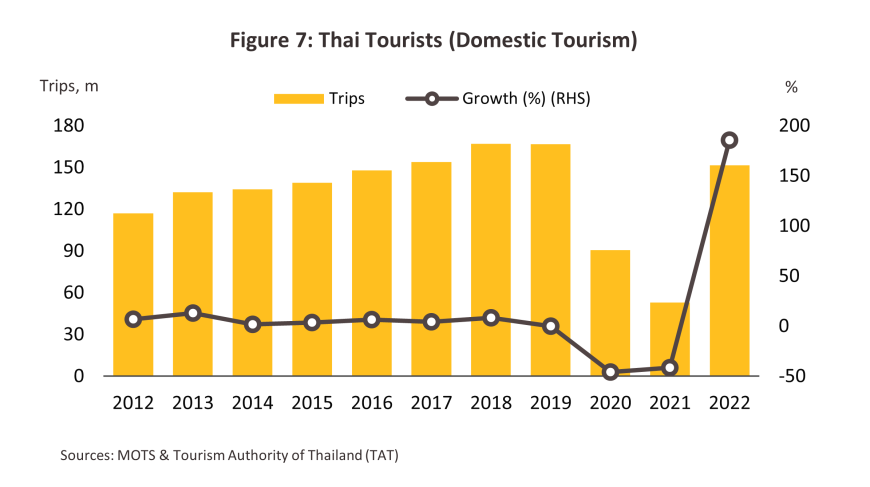

As regards domestic tourism, over the years from 2012 to 2019, annual growth averaged 5.5% with regard to the number of trips made within Thailand by domestic tourists, and this total had reached 144.8 million by the end of the period (Figure 7). Growth in the domestic market had been supported by: (i) ongoing efforts to encourage tourism, including the government’s introduction of tax refunds for expenditure on domestic tourism and the private sector’s promotion of the industry through annual travel fairs; (ii) the expansion in the services offered by low-cost airlines and the upgrade and development of provincial airports; and (iii) easier access to tourist sites for independent travelers thanks to improvements in national communications networks, especially the road system. However, with the outbreak of COVID-19 and the resulting imposition of lockdowns, curfews, and prohibitions on travel between provinces in 2020 and 2021, domestic tourism contracted by -43.6% annually to just 53.0 million trips in 2021. Nevertheless, in the following year, the market rebounded, and so in 2022 this surged 185.7% to 151.5 million trips, helped by phases 1-4 of the government’s ‘We Travel Together’ scheme. This ran over July 2020 to October 2022 and aimed to strengthen domestic tourism and so compensate for the slump in foreign arrivals.

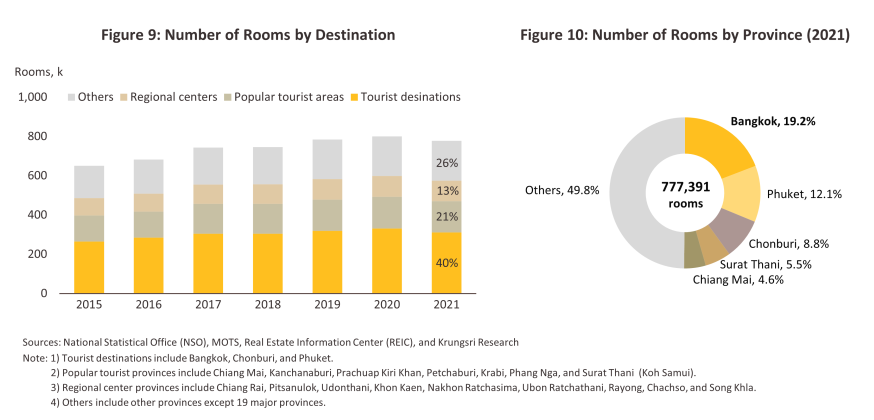

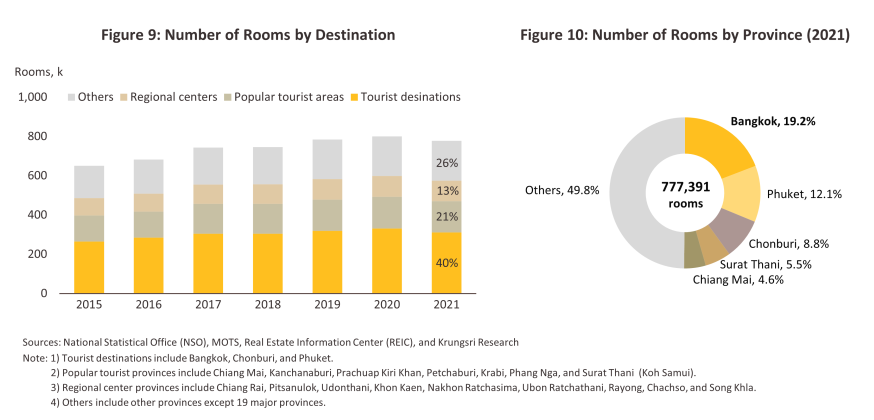

The pre-COVID expansion in the tourism sector fed into growth in the number of hotels and through this, a rise in the number of hotel rooms, especially in the major tourist centers of Bangkok, Phuket and Pattaya (in Chonburi), which is where foreign tourists tend to be concentrated. However, over the recent past, official policy has been to push for the development of tourism across the country, including in second-tier tourist centers, and to improve the standards of regional airports and the national communications network. This has then attracted inflows of private-sector investment to hotels in regional centers and in tourist areas such as Chiang Mai, Krabi and Ko Samui (in Surat Thani province). The net effect of this was then to increase the national supply of hotel rooms from 682,824 in 2016 to 799,894 in 2020, which represented average annual growth of 4.3%, but the 2020 outbreak of COVID-19 and the spread of the pandemic through the next 2 years had dramatic consequences for the hotel industry and for the tourism sector overall, and so in 2021, the supply of hotel rooms contracted -2.8% to 777,391. Both Thai and international chains are clustered in the most important tourism areas (Figure 8), and in 2021, 40% of the entire supply of hotel rooms was in these areas (Figure 9), with 165,870 in Bangkok (19% of the total), 93,746 in Phuket (12%), and 68,228 in Chonburi (9%) (Figure 10).

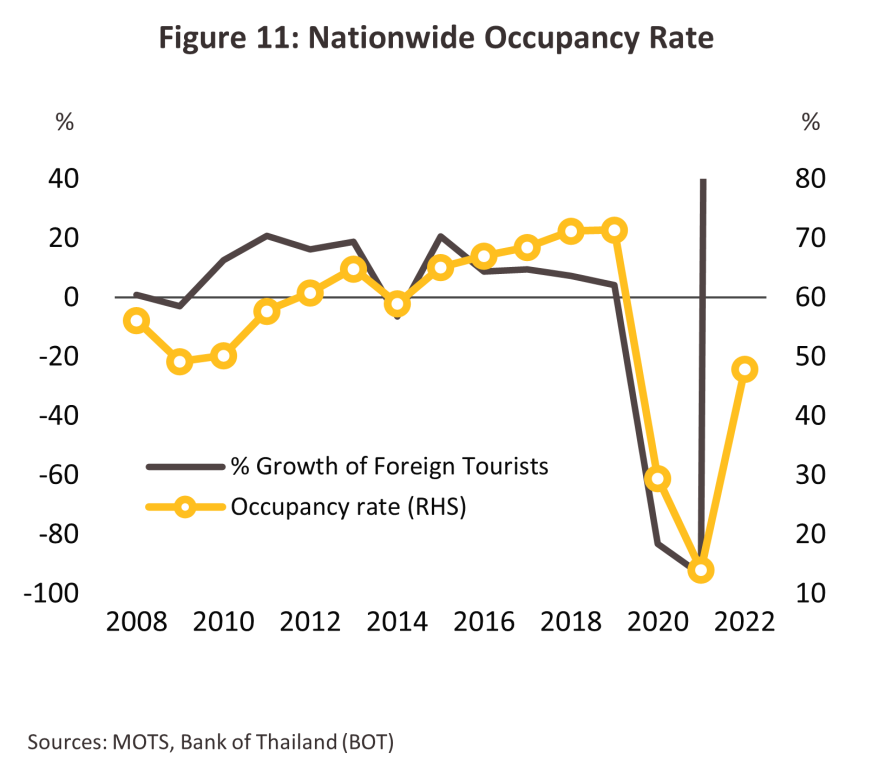

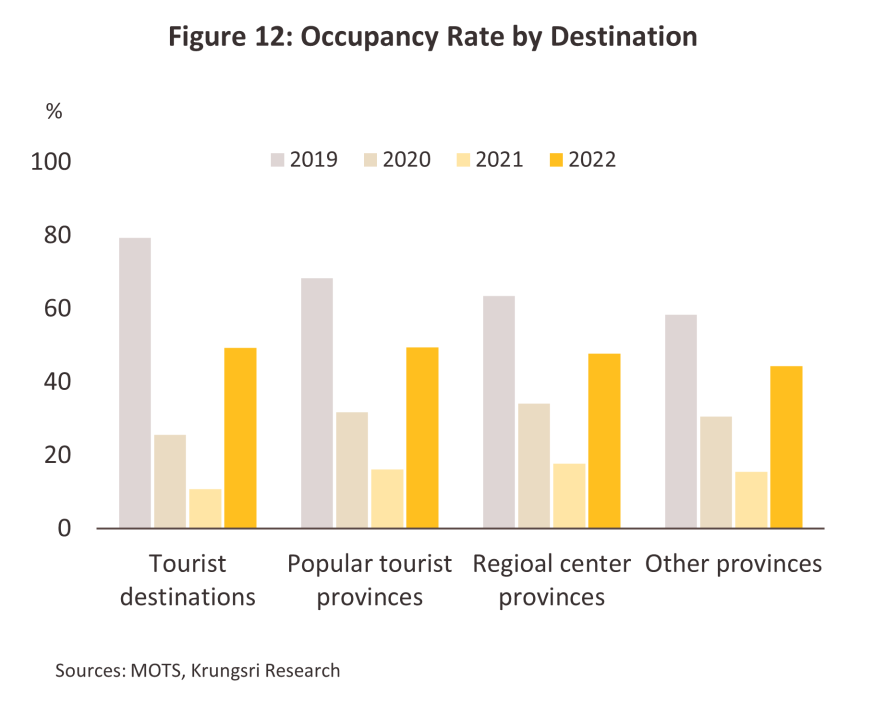

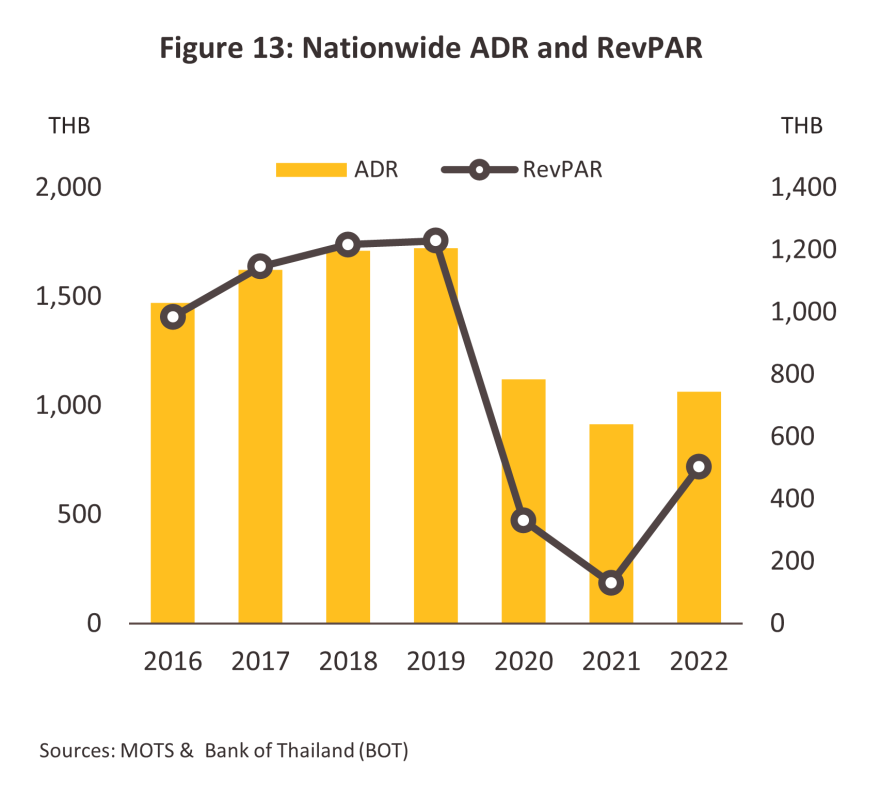

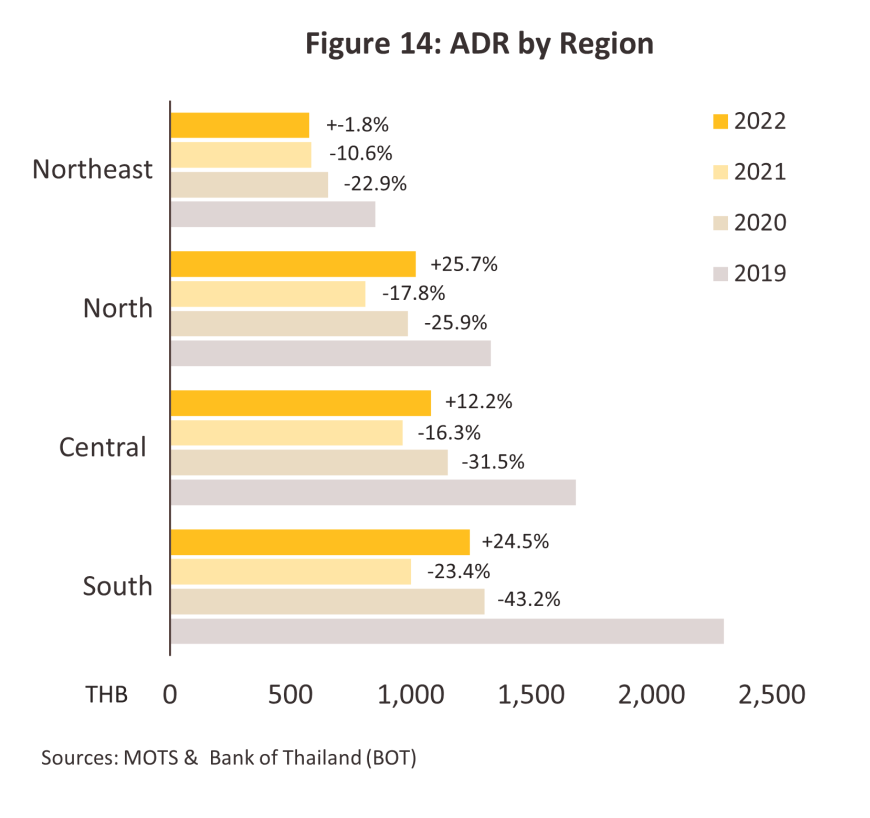

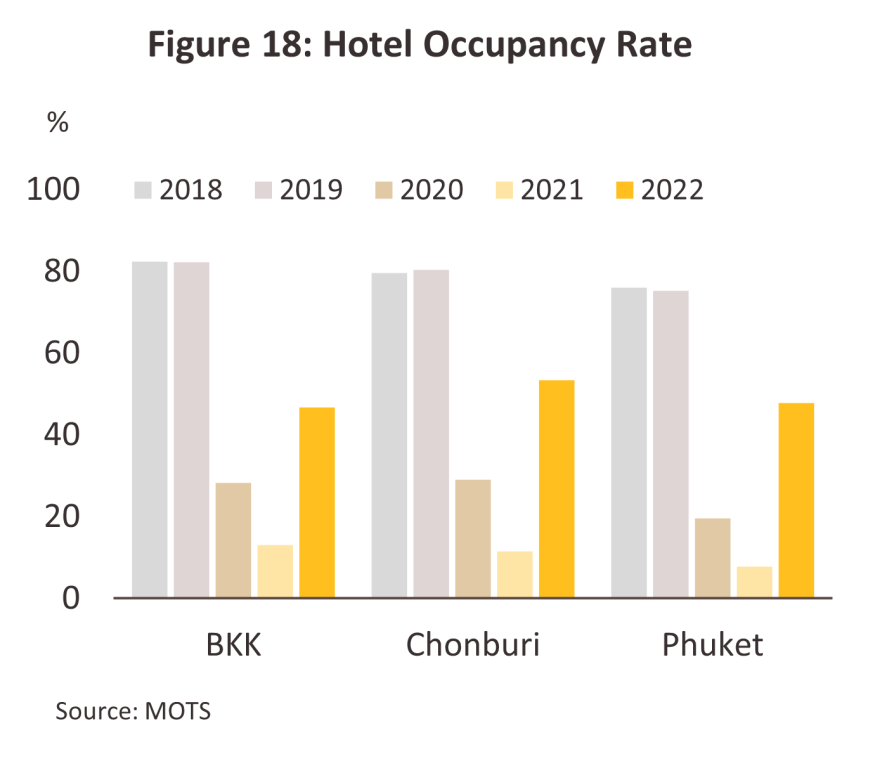

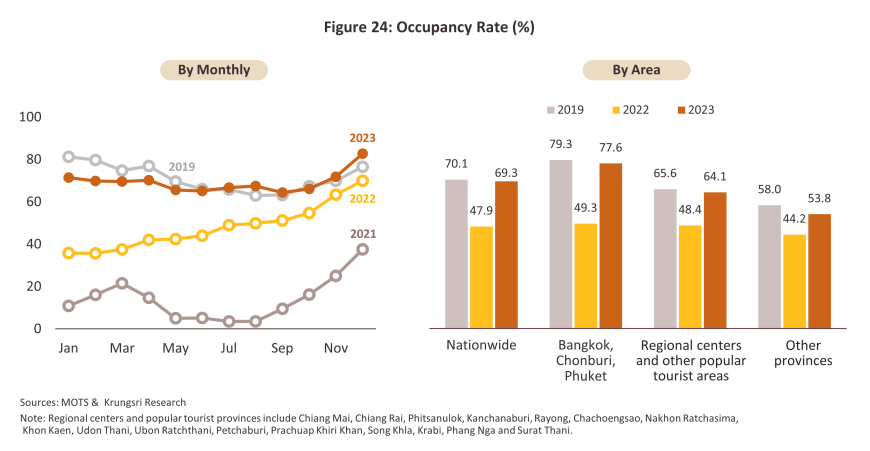

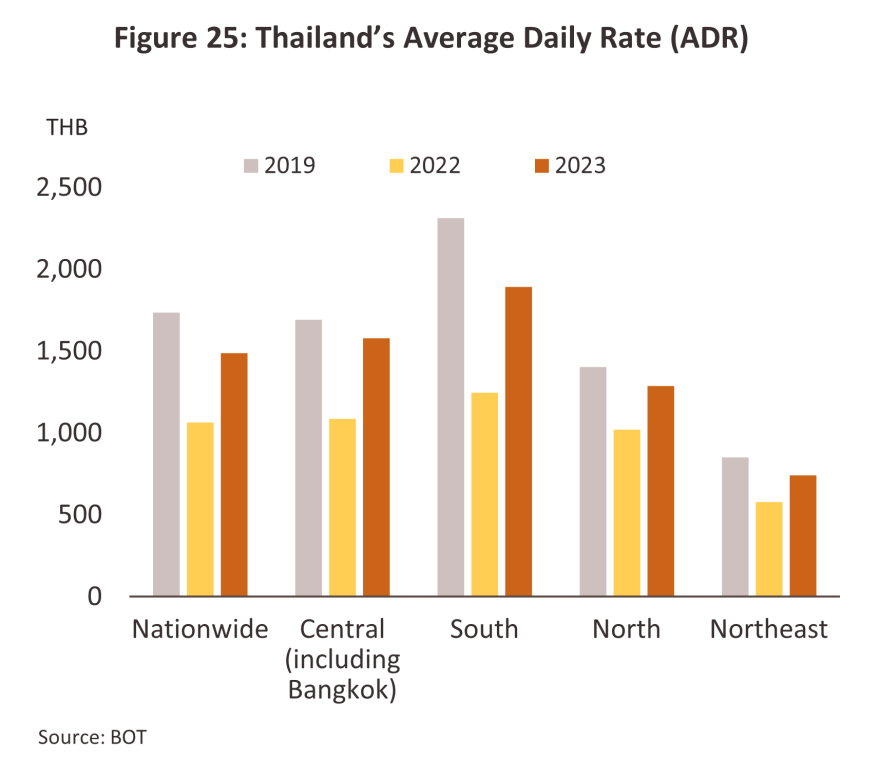

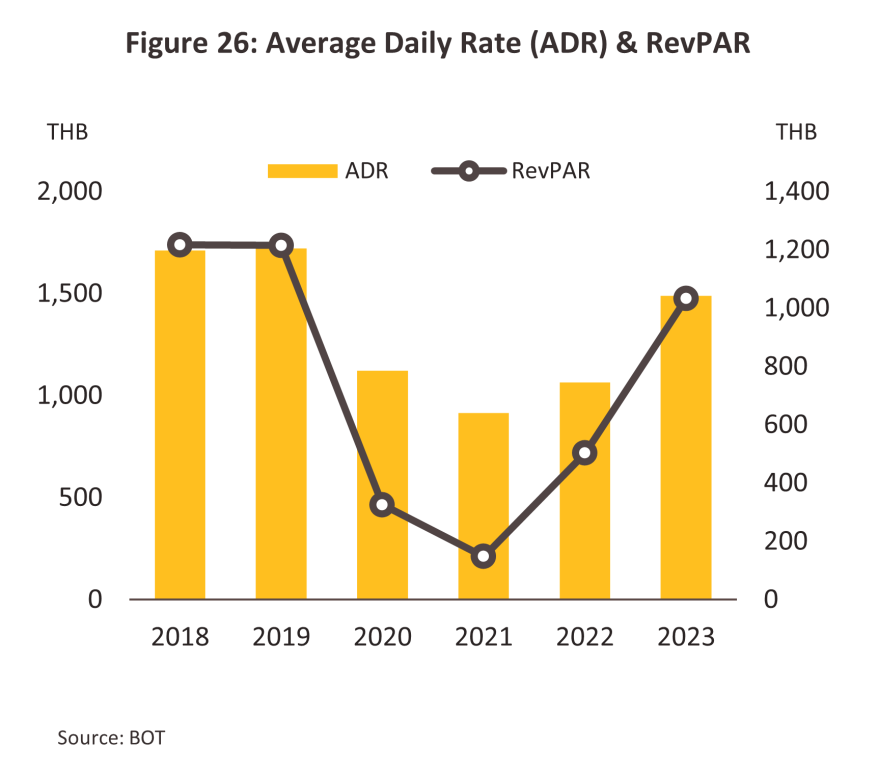

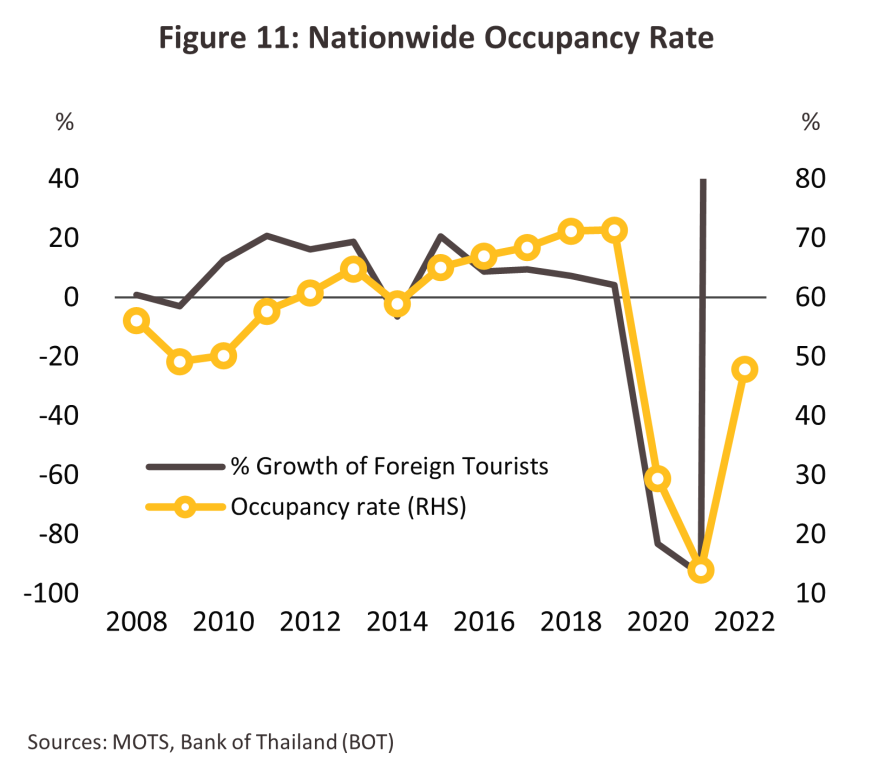

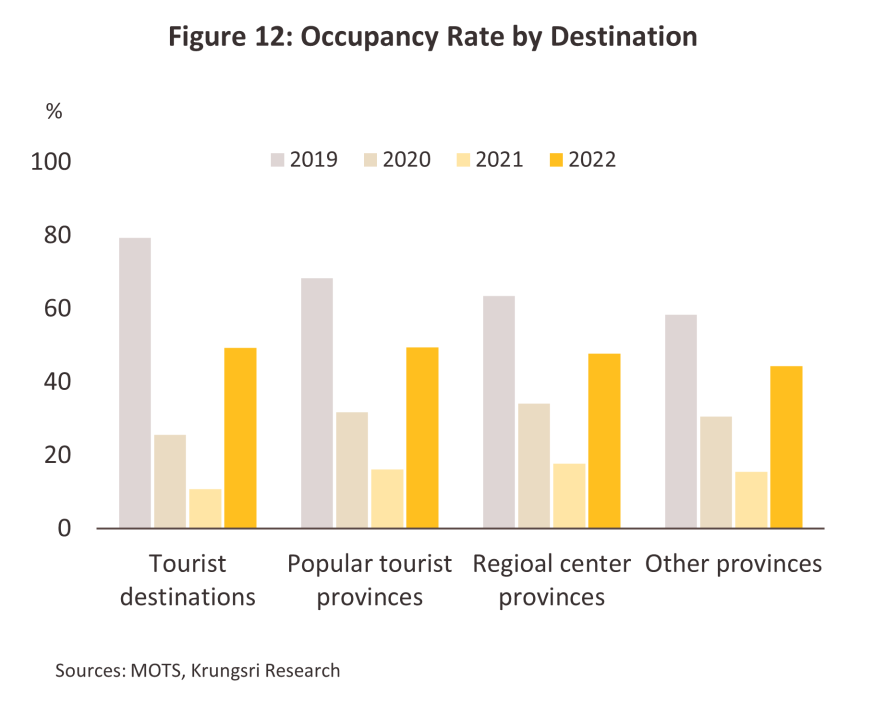

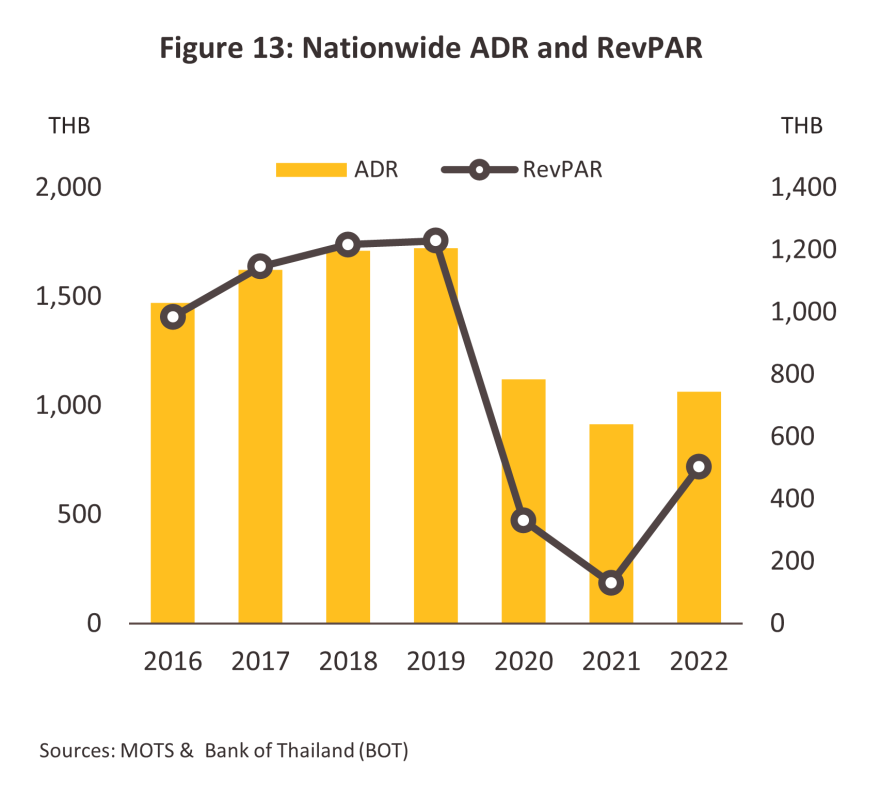

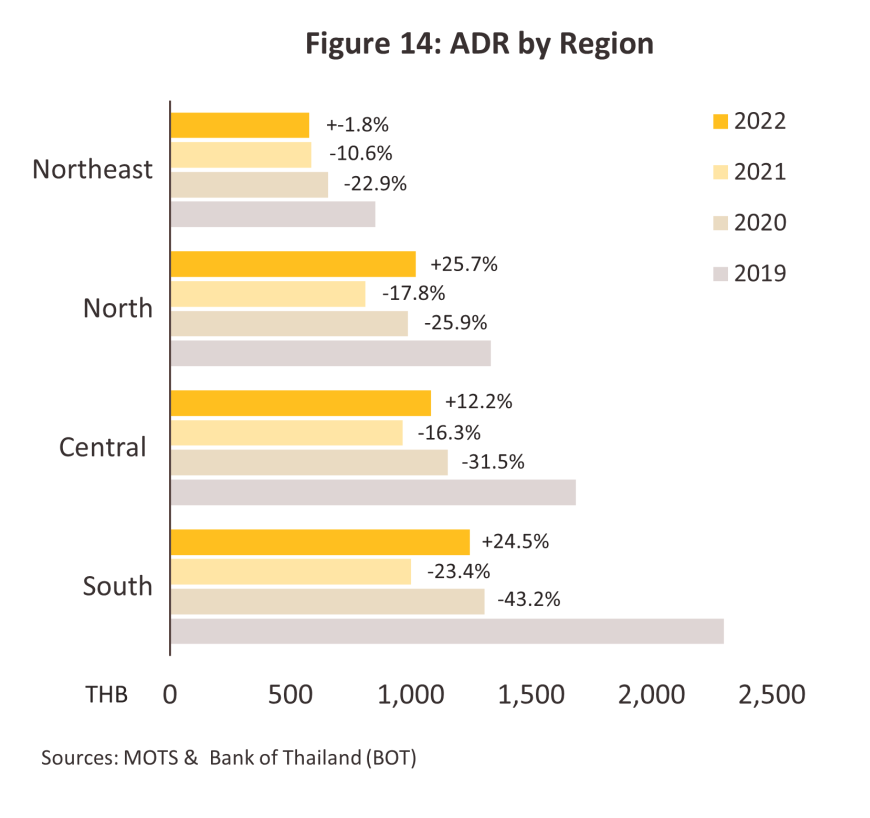

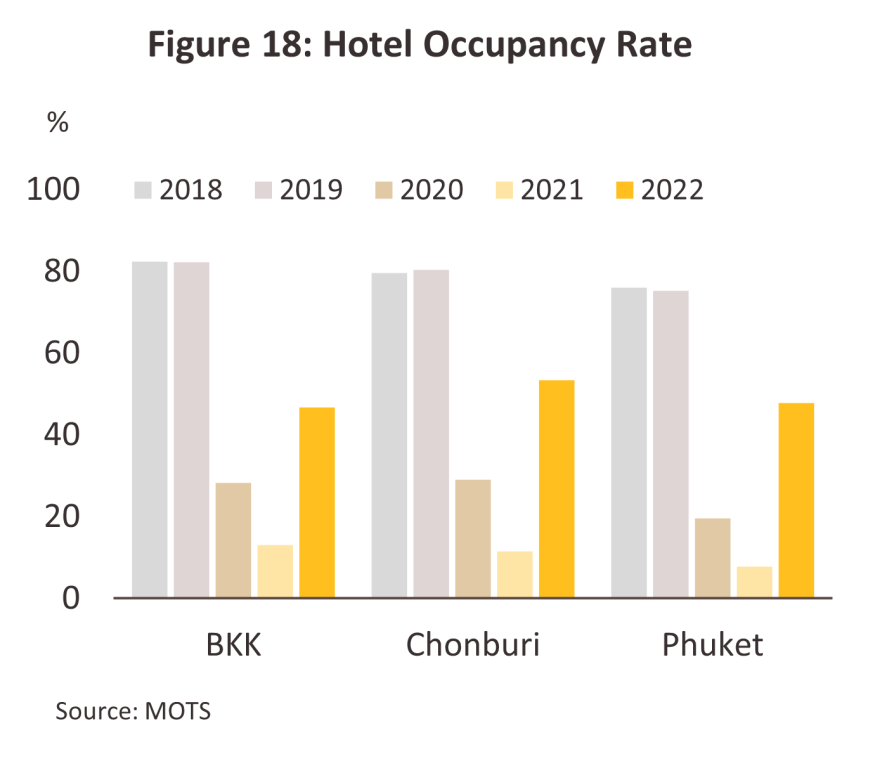

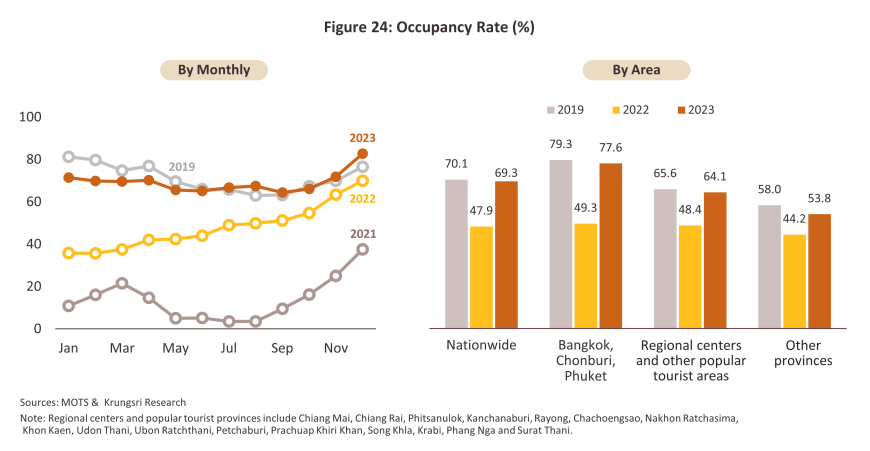

Over 2007-2019, the occupancy rate (OR) for the country as a whole tended to run in the range 60-70%3/ . However, this was also subject to the influence of external circumstances, such as when political crises have pushed this below 50%. For example, during the protests that rocked the country over 2009-2010, the occupancy rate fell to 49.7%, and during the coup of 2014, this again fell back to 58.9%. Even more extreme, the onset of the COVID-19 crisis in 2020 pulled the occupancy rate down to 29.5% and then to just 14.2% in 2021 as both domestic and international tourists disappeared from the market. The situation improved markedly in 2022, with the OR climbing back to 47.9% (Figure 11). In the main tourist areas, the OR came to 49.3% (+38.5ppt), very close to 49.4% (+33.4ppt) recorded in other major tourist areas such as Kanchanaburi, Chiang Mai, and Prachuap Kiri Khan (Figure 12); in these areas, rapid growth in the domestic market was able to go some way towards offsetting the continuing weakness in foreign arrivals. Similarly, the 2019 pre-COVID average daily rate (ADR) of THB 1,700/room slumped to THB 1,121/room in 2020 (-34.9%) and then to THB 914/room (-18.5%) in 2021, with predictable effects on the average revenue per available room (RevPAR) (Figure 13). Because hotels in the south are more dependent on foreign arrivals (who tend to prefer seaside resorts), average room rates in the south saw the biggest fall of any region during the pandemic (Figure 14).

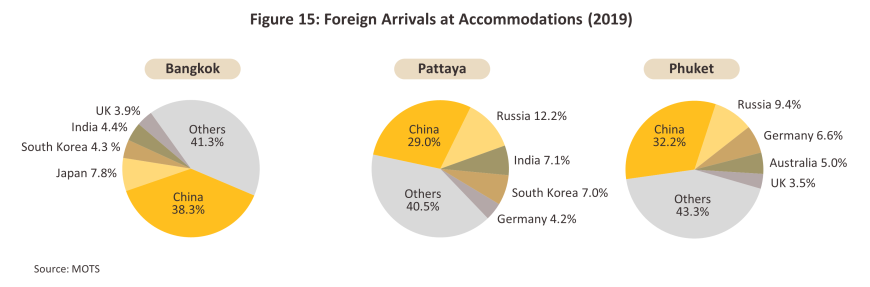

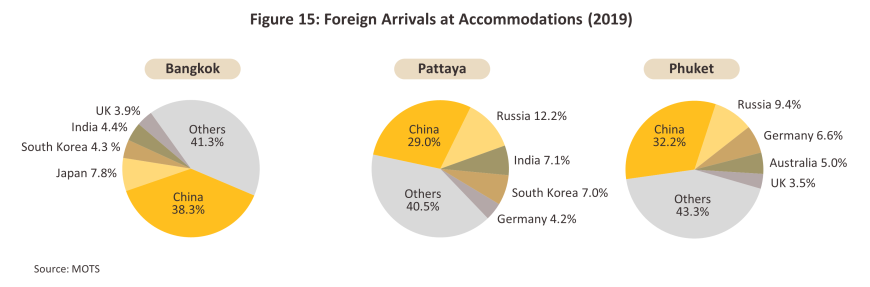

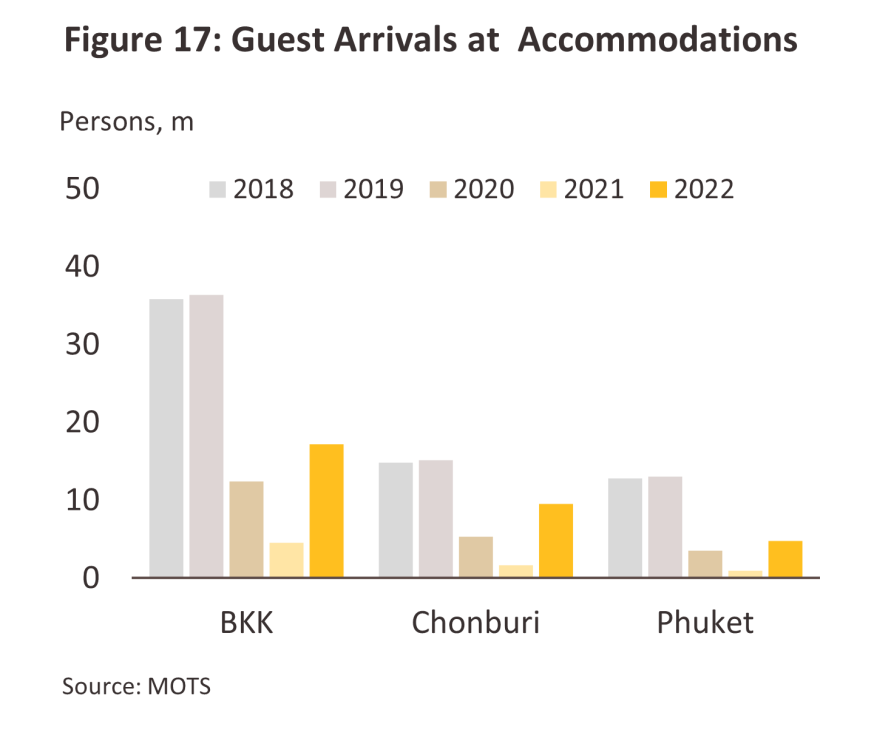

Within the primary tourist areas of Bangkok, Chonburi and Phuket, the spread of COVID-19 through 2020 and 2021 had enormous consequences for the tourism industry generally and hoteliers in particular. Lockdowns imposed in originating countries and in Thailand cut the flow of outbound tourists, and so arrivals contracted precipitously. The Chinese segment, which had become the most important market for hotels in these areas (Figure 15), was particularly hard hit following the imposition of the 2020 ban on outbound travel by the Chinese government. However, as the pandemic eased through 2022, international travel began to pick up again, and with this, the occupancy rate began to rebound. The situation in the main tourist areas is outlined below.

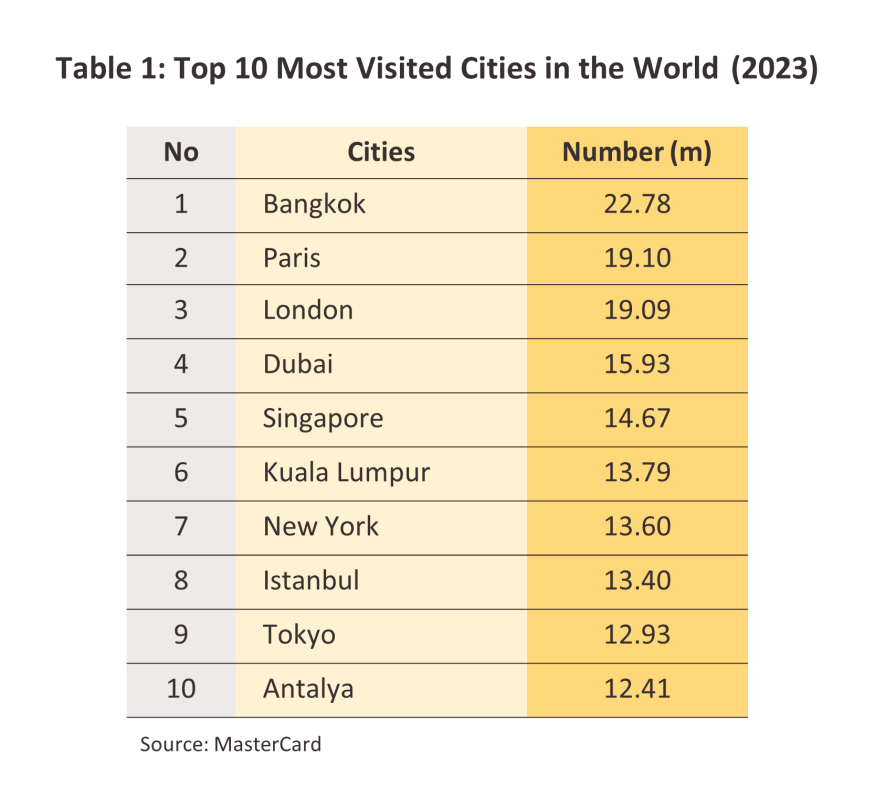

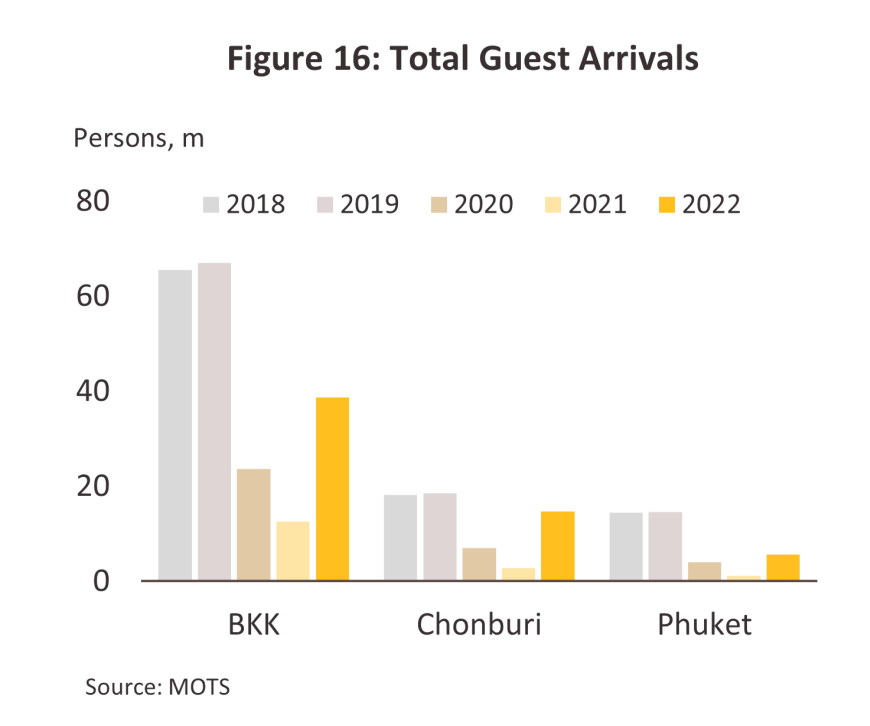

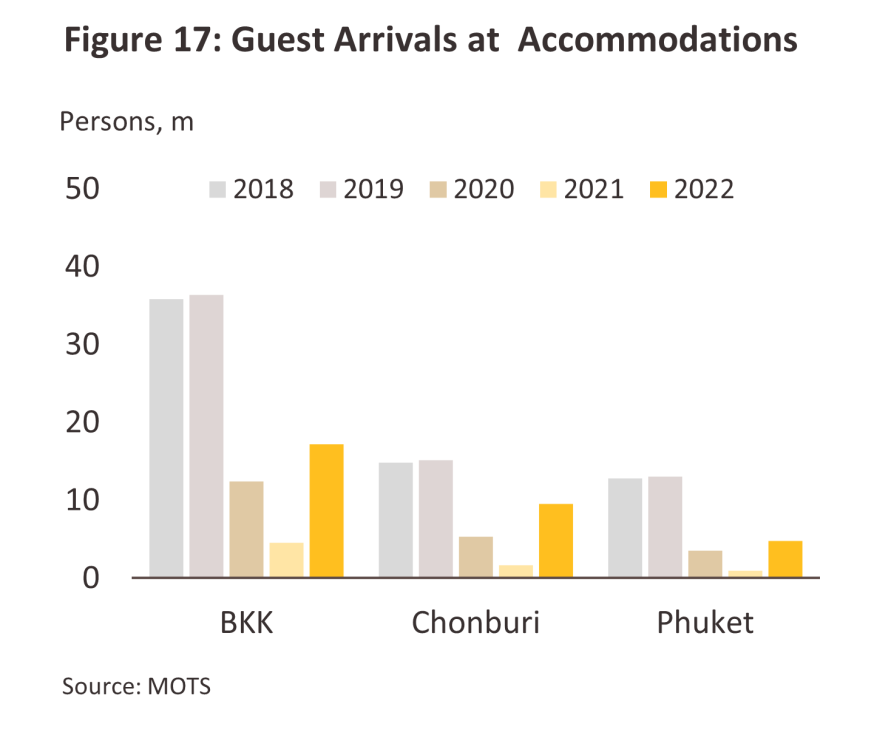

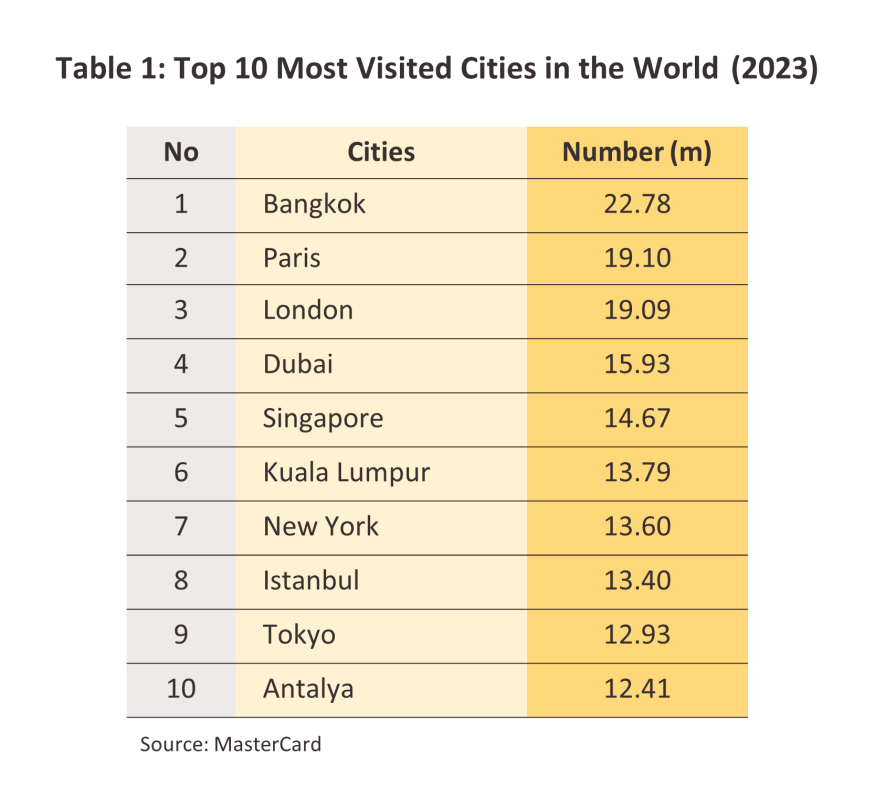

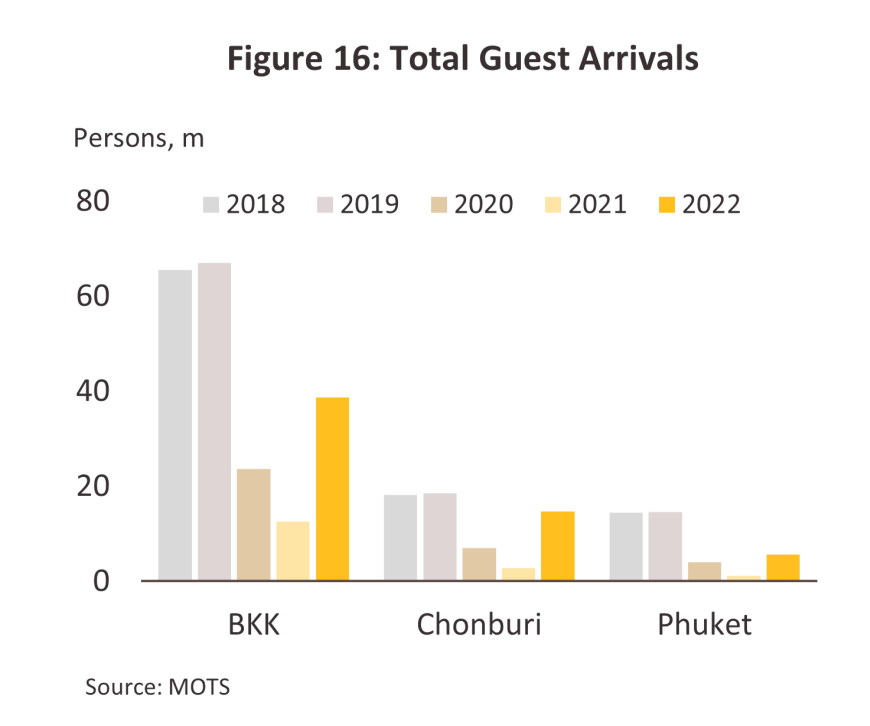

Bangkok: The capital is not just the country’s most important tourist attraction, it is also a major global destination, a fact reflected in the numerous travel awards presented to the city4/. Factors helping to keep Bangkok high in the rankings of global tourist attractions include: (i) the city’s location at the center of both Thailand and the wider ASEAN region, which then helps to make onward travel much more convenient; (ii) the generally low costs relative to other major cities in the region; (iii) the wide range of hotels, with options available at all levels of the market; and (iv) the huge range of entertainments that are available, from temples to nightlife. However, having grown by 1.2% annually over 2017-2019 to a total of 65 million visitors annually (split 64% Thais and 36% non-Thais), visitor numbers crashed on the outbreak of the pandemic. In 2020, these thus fell -55.3% to 23.6 million, and in the following year, these slumped by another -36.4% to reach just 12.6 million. Recovery began in 2022, and data from Mastercard show that as of 2023, Bangkok was the most visited city in the world (counting both travelers staying overnight and those traveling onwards in the same day) (Table 1). This has helped to lift the average occupancy rate back to 46.6%, though this remains a long way off 2019’s 82.2% (Figures 16-18).

Pattaya/Chonburi: This seaside resort on the east of Thailand has long been globally famous as a top-tier destination, but the importance of the area has increased with the designation of Chonburi as part of the Eastern Economic Corridor Development (EEC), and as such, Pattaya is now attracting attention from investors and the business community as well as from tourists. Chonburi is visited by around 18 million people annually, with 84% going to Pattaya (a mix of both Thai and foreign tourists) and 16% going to Bang Saen (mostly Thai tourists). Occupancy rates went as high as 80% pre-COVID before crashing to a historic low of 11.5% in 2021, but as of 2022, these had recovered to 53.3% (Figures 16-18).

Phuket: Thailand’s other major seaside tourist destination is in the south of the country, and thanks to Phuket’s status as a stunning tropical island, it is widely known as ‘the pearl of the Andaman’. Tourist attractions dot the western side of the island, including Patong, Kata, Karon, and Mai Khao beaches, while on the east, tourists can visit Rawai Beach, Cape Panwa, and Ko Lon. Phuket differs from Pattaya in several ways.

1) In Phuket, demand is largely driven by the tourist industry, whereas in Pattaya, this comes from a combination of tourism and industry. This is because Pattaya is situated near several major industrial estates, and the area has benefited from government support, most importantly through the creation of the Eastern Economic Corridor.

2) Phuket is much further from Bangkok than Pattaya and so traveling by road or rail is much less convenient. Because of this, in 2019, only 26% of hotel bookings made in Phuket were from Thai visitors compared to 34% in Pattaya, leaving Phuket hotels much more dependent on the overseas market. In addition, occupancy rates have traditionally been lower in Phuket than in Pattaya. This was especially so through 2020 and into 2021, despite the introduction of the ‘Phuket Sandbox’ in the second half of the year, and although the occupancy rate rose through 2022, the only partial recovery in foreign arrivals meant that this remained lower than in Pattaya (Figures 16-18).

Situation

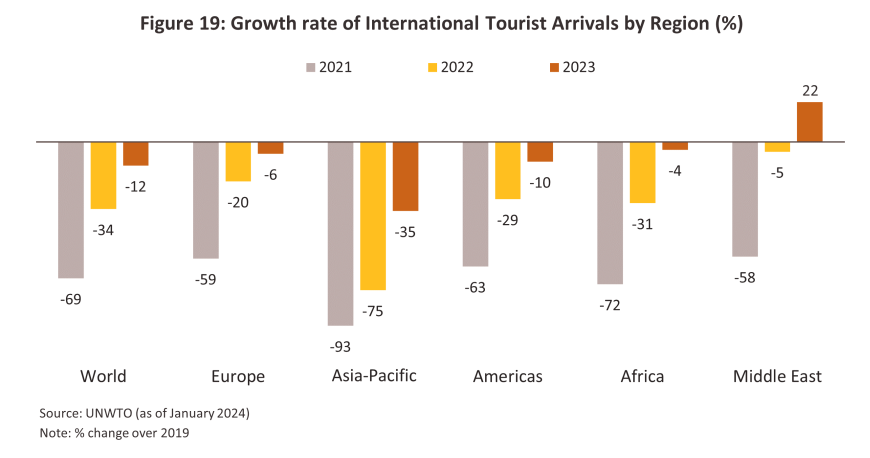

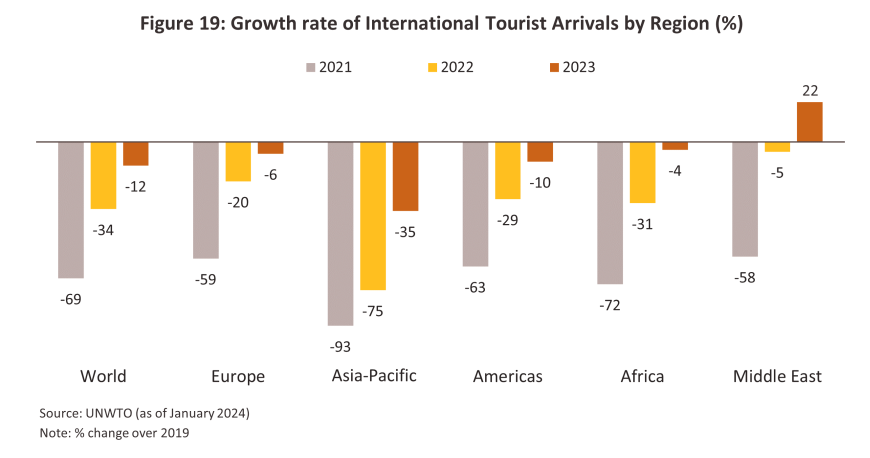

The global outlook for hoteliers and the tourism industry generally improved through 2023 as the effects of the COVID crisis, which had dragged so heavily on the industry since 2020, began to dissipate with the wholesale lifting of pandemic restrictions and the rebound in international travel. (This was with the exception of China, where the zero-COVID policy prevented outbound tourism until the start of 2023). For the year as a whole, 1.3 billion international arrivals were recorded globally, up around 35% from the 2022 level of 960 million. The overall market was boosted by several years of pent-up demand and the steady increase in the number of international flights, though 2023 travel was still -12% below the pre-COVID total (Figure 19). Relative to the 2019 baseline, the fastest rate of growth was seen in the Middle Eastern market, which has expanded 22%, while due to continuing sluggishness in the Chinese segment, the Asia Pacific market has been the worst performing (still down -35%).

In the year, the Thai market mirrored global trends and so hoteliers and the tourism industry generally enjoyed ongoing recovery through 2023.

-

28.15 million foreign arrivals were recorded in 2023, up from just 11.06 million in 2022, with December 2023 arrivals reaching 3.26 million, their highest since February 2020 (Figure 20). In the year, the most important originating nations were Malaysia (4.6 million), China (3.5 million) and South Korea (1.7 million) (Figure 21). Arrivals have been boosted by the decision by the Chinese authorities to allow outbound tourism from the start of the year. Initially, independent travel was permitted from 8 January, with group tours then allowed to 20 countries5/ including Thailand on 6 February (this had been blocked since the start of 2020) before the list was expanded to more than 70 countries on 10 August. The number of international flights and routes has also increased steadily, and for the 2023 financial year, these were up 124.6% YoY6/.

Despite this, 2023 tourist arrivals were still only 70% of the pre-pandemic total of 39.9 million. Some markets have performed well, and arrivals from South Korea and India are back to respectively 88% and 83% of their 2019 level, while at 108% and 100%, those from Malaysia and Russia are at or exceeding their pre-COVID level. However, at just 32% of the 2019 total, the all-important Chinese market remains sluggish. This is for a number of reasons, including tighter checks on visa applications introduced to prevent Chinese arrivals carrying out business illegally in Thailand (for example, applicants are now required to present bank statements with their applications). As such, the time taken to process tour group visas for Chinese arrivals has increased from the pre-COVID 3-5 days to up to 15 days. In addition, the number of flights from China to Thailand is insufficient to fully meet demand, and ticket prices remain elevated.

-

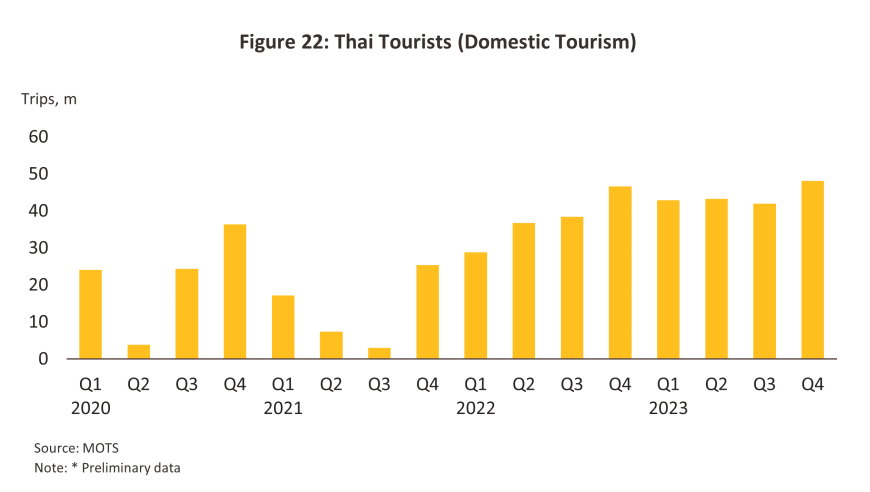

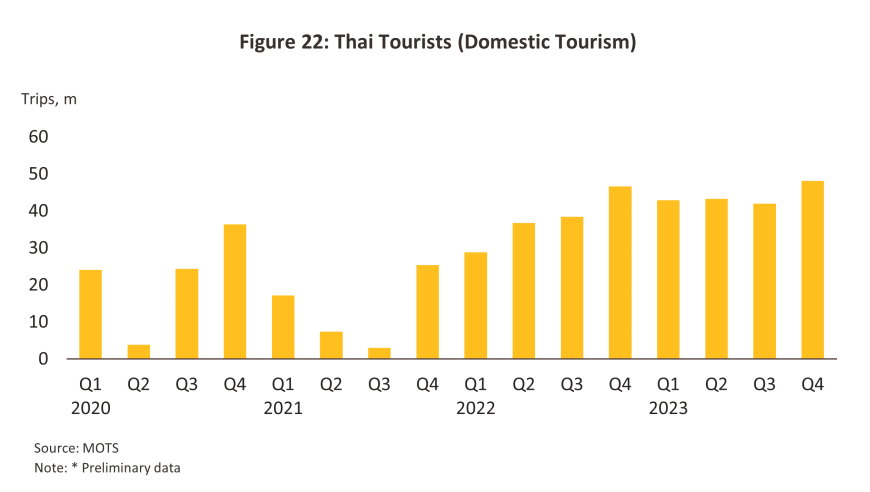

Thai tourists made 176.3 million trips in 2023, a jump of 69.5% from a year earlier (Figure 22). By quarter, these were split: 42.9 million trips in Q1 (+48.9% YoY), 43.3 million trips in Q2 (+17.8% YoY), 42.0 million trips in Q3 (+9.3% YoY), and 48.1 million trips in Q4 (+3.3% YoY). The market was boosted by: (i) the large number of 3-day public holidays, including Makha Bucha, Songkran (the risk of spreading COVID-19 meant that this had not been celebrated for the previous 3 years), Labor Day, and Coronation Day; (ii) phase 5 of the ‘We Travel Together’ scheme (from 7 March to 30 April, 2023); and (iii) promotional activities carried out by both the public sector (e.g., the 41st Thailand Tourism Festival) and the private sector (e.g., discounts for hotels, package tours, and restaurants between May and August, 2023, offered by companies in the tourism industry during ‘Green Season’).

-

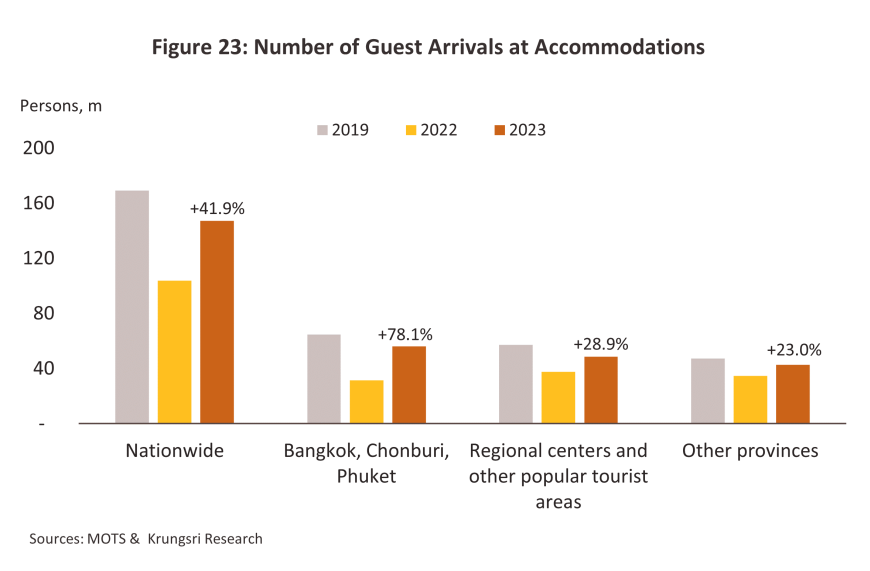

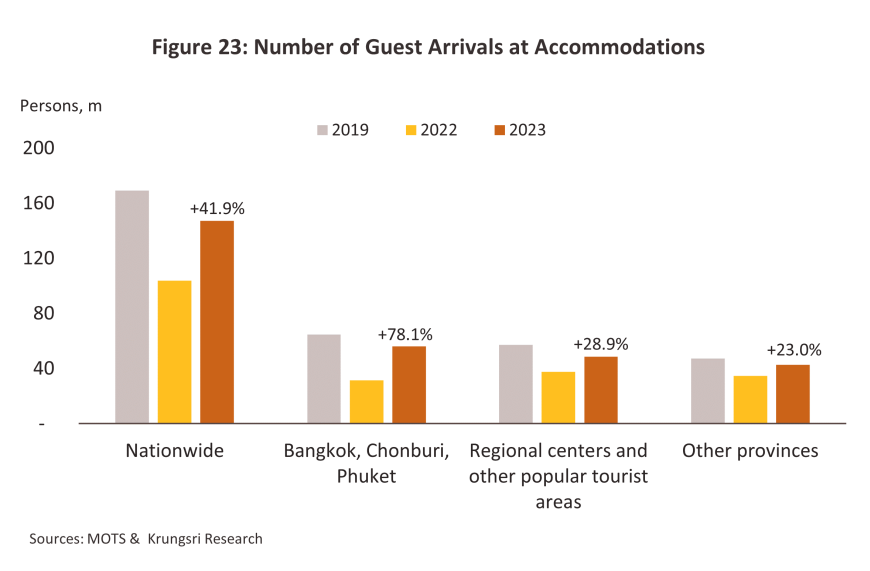

Total 2023 guest arrivals at accommodation rose 41.9% to 147.2 million. In the main tourist areas of Bangkok, Chonburi and Phuket, where hotels are more reliant on overseas visitors, guest arrivals jumped 78.1% to 56.1 million, hotels in these areas thus accounting for 38% of all guest arrivals in the year. This was followed in importance by other tourist areas and the 16 regional centers, where hotels are still reliant on the overseas market though less so and where arrivals increased 28.9% to 48.5 million (33% of the total). Finally, other areas are mostly dependent on the domestic market and in these locations, visitors often make one-day trips. As such, guest arrivals increased just 23.0%, hitting 42.5 million, or 29% of the total (Figure 23).

-

The average national occupancy rate (OR) jumped from 47.9% in 2022 to 69.3% in 2023, bringing this back to close to its 2019 level of 71.4%. In the three main tourist destinations, the occupancy rate rose above 75% on the strength of the tourism market, especially of foreign arrivals. The occupancy rate was next highest in regional centers and tourist areas, and was lowest in other parts of the country (Figure 24).

-

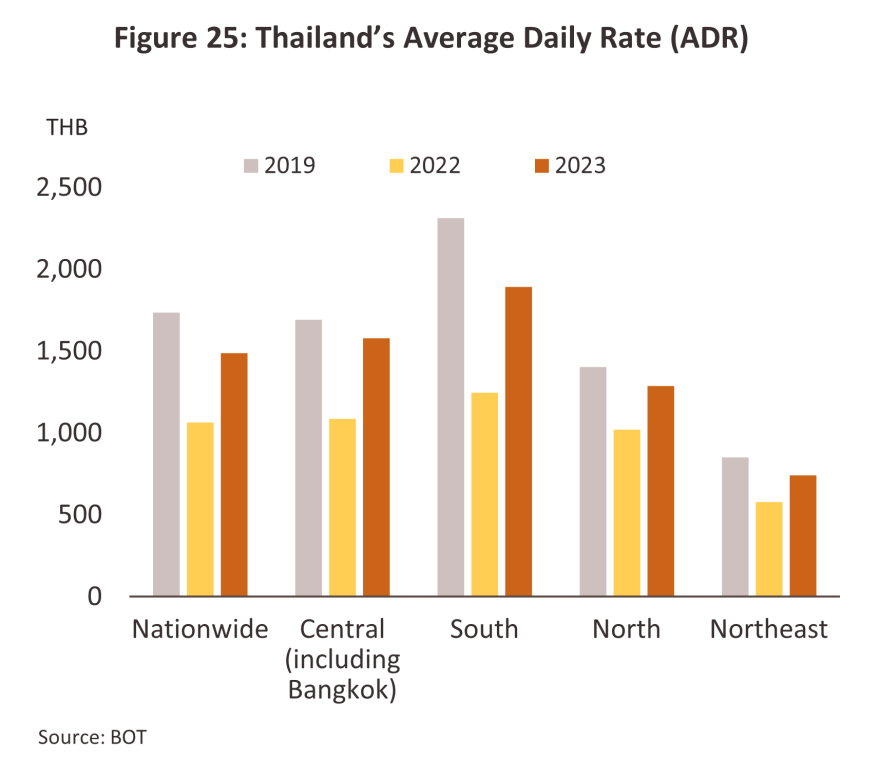

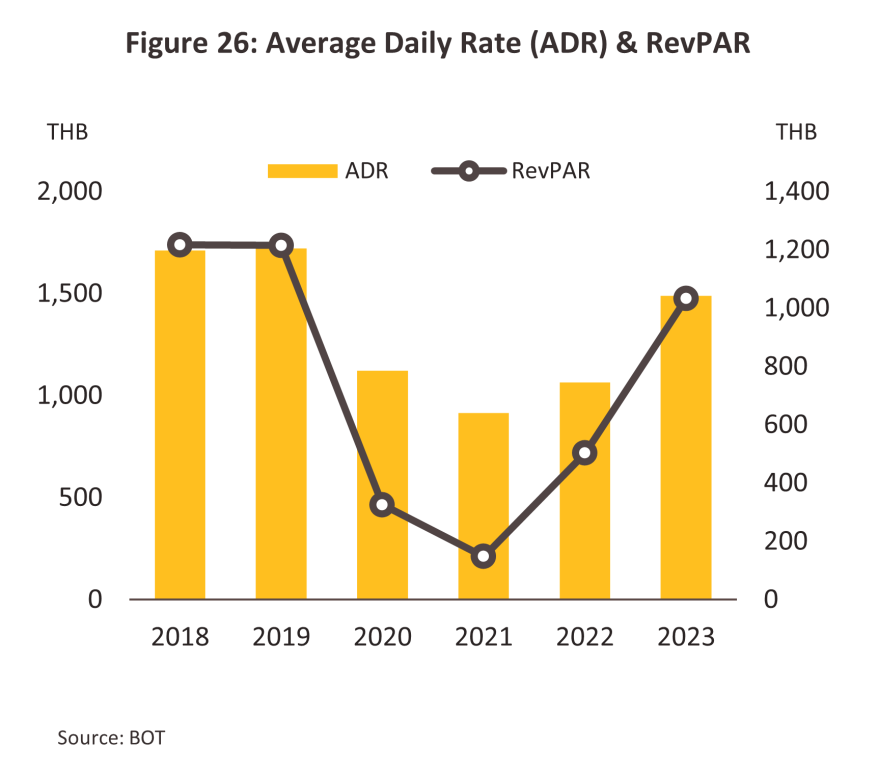

The 2023 average daily rate across the country (ADR) rose 40.0% to THB 1,488, though this was still down -14.2% from the 2019 level. Rooms in the south of the country were the most expensive, with rates for these averaging THB 1,891 per night (+51.7%). Hotels in the south typically benefit from their seaside location, and because these are in higher demand (especially among overseas visitors), hoteliers can charge higher rates than in other locations. By contrast, due to low visitor numbers and reduced occupancy and room rates, ADRs in the northeast of Thailand remain the lowest, with these averaging THB 742 per night (Figure 25). In addition, the increasing occupancy rate and room rates raised revenue per available room (RevPAR) to 105.3% in the year to THB 1,032 (Figure 26), though again, this remained below the 2019 RevPAR of THB 1,215.

2023 data from Trivago show that the average daily room rate in Bangkok (for hotels of all levels) was just THB 2,267, or not much more than a quarter of Singapore’s average rate of THB 7,782 per night and slightly less than Kuala Lumpur’s THB 2,380 (Figure 2). Combined with the low cost of living, the cheap rates available in Bangkok make hotels in the city highly competitive relative to other cities in the Asia-Pacific region, and the overall value for money provided to overseas visitors means that Thailand will continue to attract large numbers of foreign arrivals.

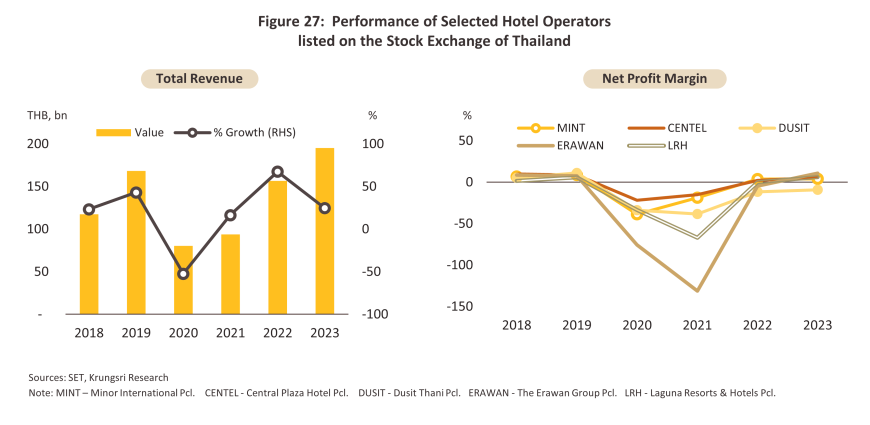

- Turnover has recovered within the industry, and for the 5 hotel operators registered on the Thai stock exchange (Figure 27), 2023 turnover was up 24.5%, while net profits turned around from 2022’s loss of -2.0% to an average gain of 3.4%. Nevertheless, circumstances can vary widely for individual businesses, depending on the structure of their operations and the extent of their diversification. Thus, Central Plaza Hotel (CENTEL) and Minor International (MINT) have been able to generate income from alternative sources, including food services and fashion sales, which will tend to expand in step with growth in the domestic tourism industry generally.

Outlook

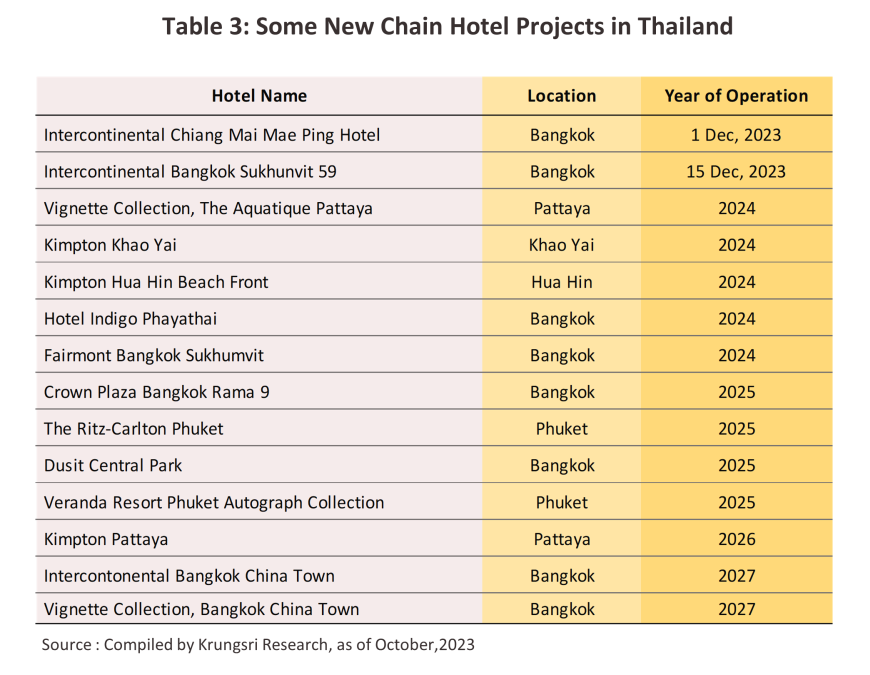

Conditions in hotel industry will continue to improve through 2024-2026. Annual foreign arrivals should return to their pre-pandemic total of 38-40 million in 2025, boosted by ongoing government measures targeting the industry. However, geopolitical stresses including the war in Ukraine and the fighting in the Gaza Strip will work as headwinds blowing against international travel, especially from the Middle East. Domestic tourism will also continue to expand, and 200 million trips are expected to be made by domestic tourists this year. On the supply side of the market, major hotel operators will continue to invest in expanding their services, especially in the major tourist destinations, and for 2024, the national occupancy rate is forecast to rise above 70%.

-

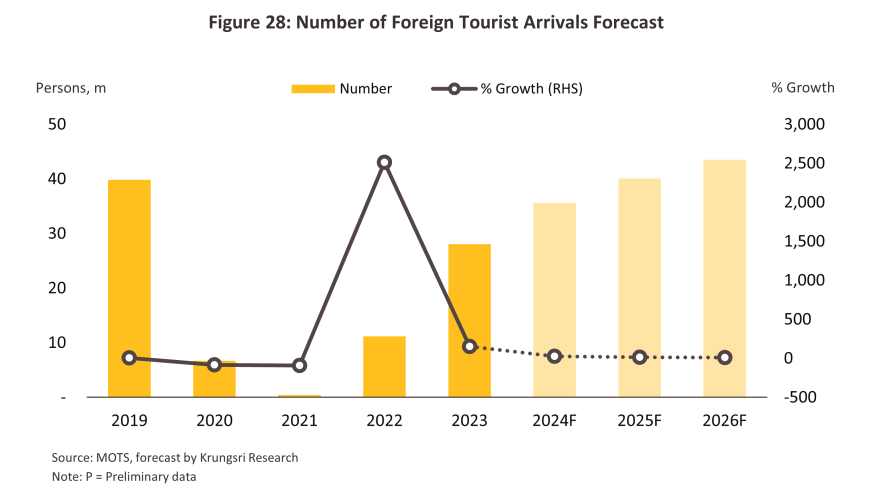

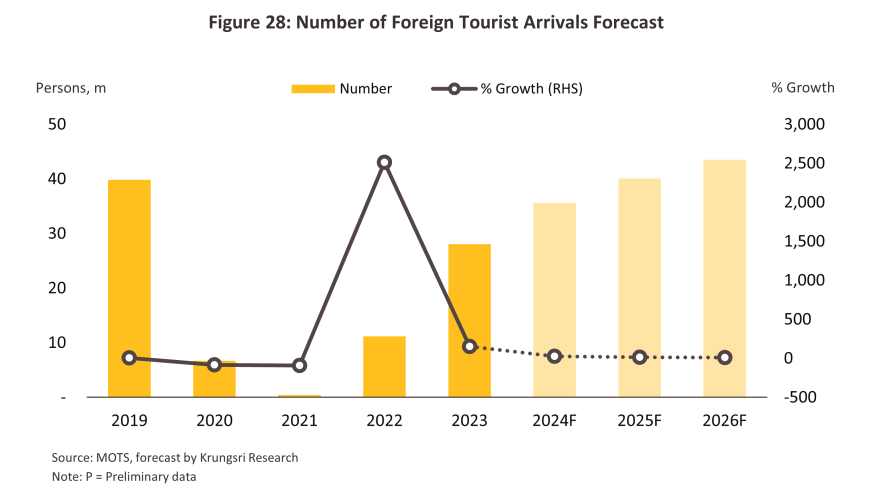

The rapid rebound in foreign arrivals will continue, and Krungsri Research sees these reaching 35.6 million in 2024 (during 1Q2024, number of foreign tourists surged 44.0% YoY to 9.4 million), 40.0 million in 2025, and 43.0 million in 2026 (Figure 28). Tailwinds supporting this outlook will include the following.

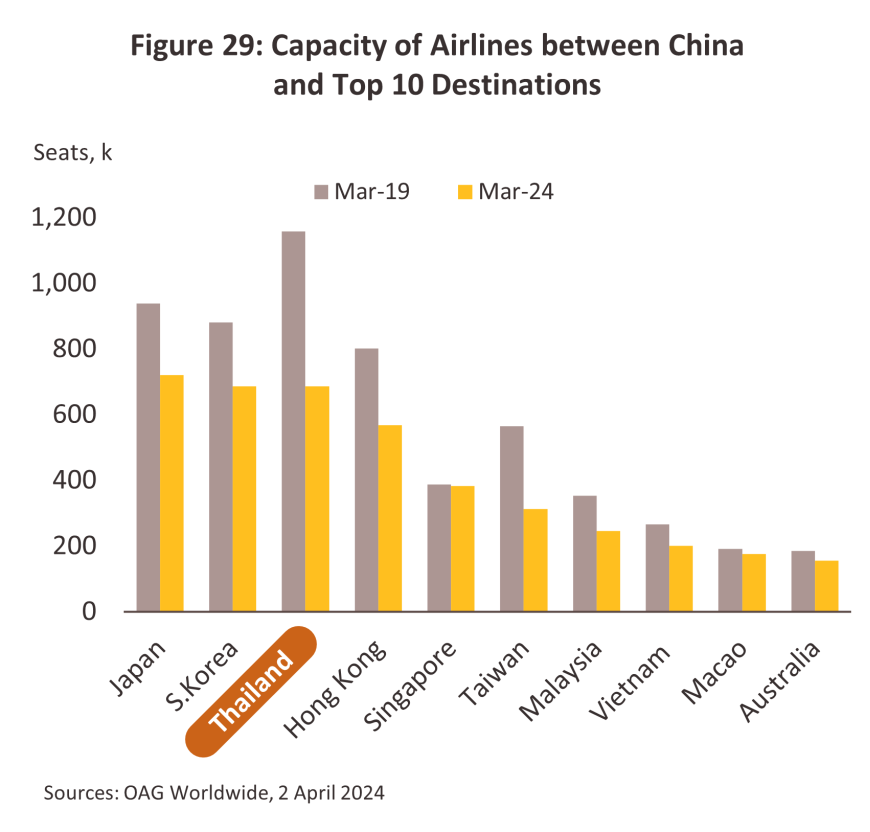

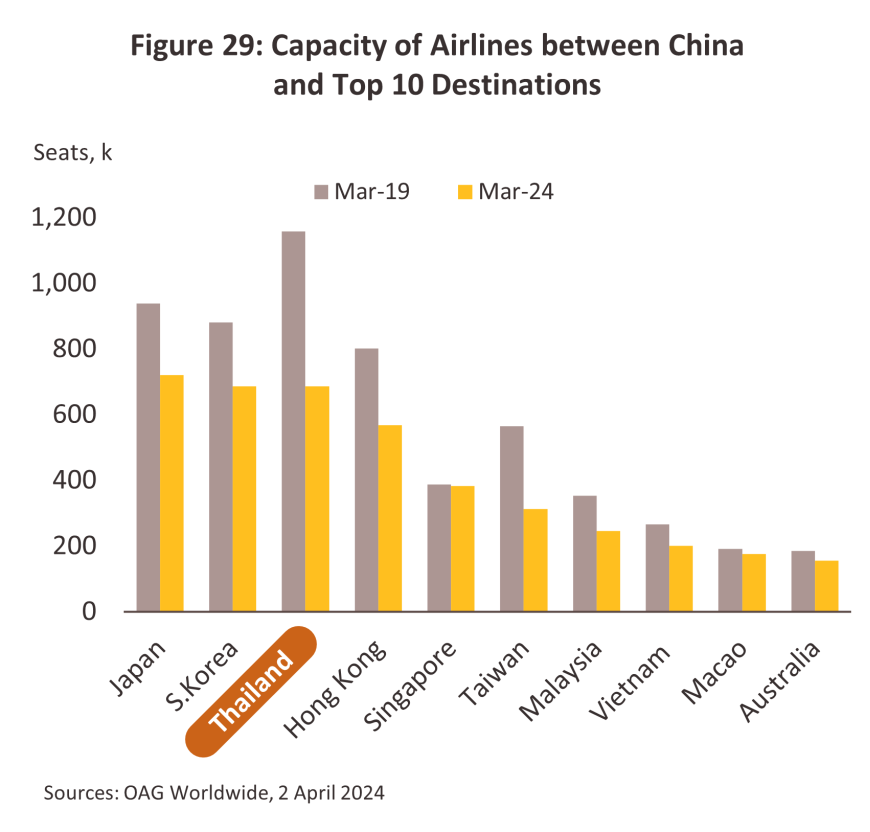

1) Arrivals from the main markets will continue to rise, although recovery in the Chinese market will remain relatively slow. The poor performance of the Chinese economy is encouraging many Chinese to travel domestically, while the capacity of flights linking Thailand and China has still not returned to its 2019 level (Figure 29). Nevertheless, Thailand remained a favorite destination for Chinese citizens planning to travel abroad in 2023 (Table 2). This will help to drive continuing recovery over 2024-2026.

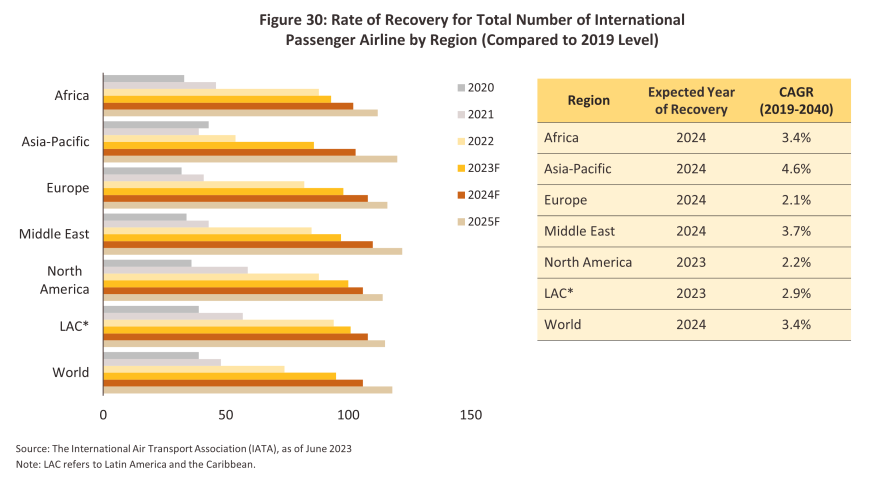

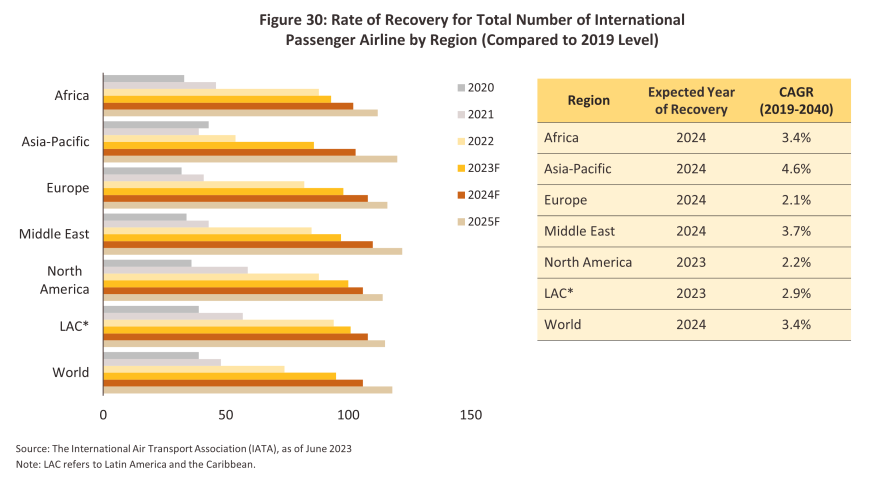

2) International air travel should return to normal in 2024 (Figure 30).

3) Ongoing government measures providing additional support for the industry include: (i) the permanent granting of visa-free travel for Chinese tourists from March 1, 2024; (ii) the granting of visa-free travel for Indian and Taiwanese tourists between November 10, 2023 and May 15, 2024; (iii) the extension of visa-free travel for Kazakh tourists for another 6 months, taking this to August 31, 2024 (from the earlier end date of February 29, 2024), and although at less than 1% of the total, Kazakh arrivals are currently very limited, the market is expanding and has significant spending power7/; (iv) the extension of the permitted length of stay for Russian arrivals traveling without a visa from 30 to 90 days between November 1, 2023, and April 30, 2024; and (v) roadshows promoting Thai tourism in high-spending new markets, in particular in the Middle East.

-

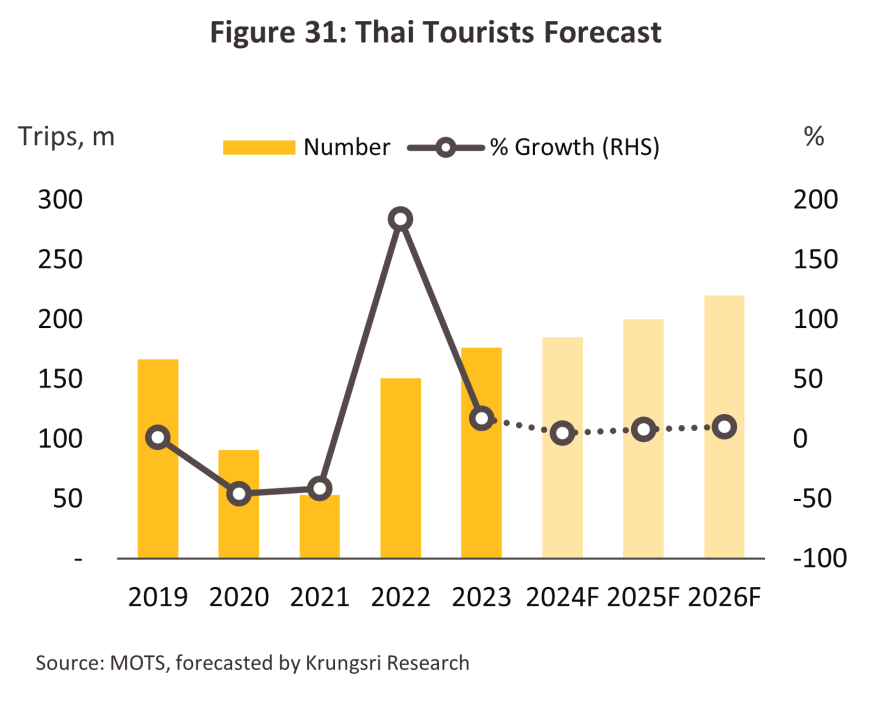

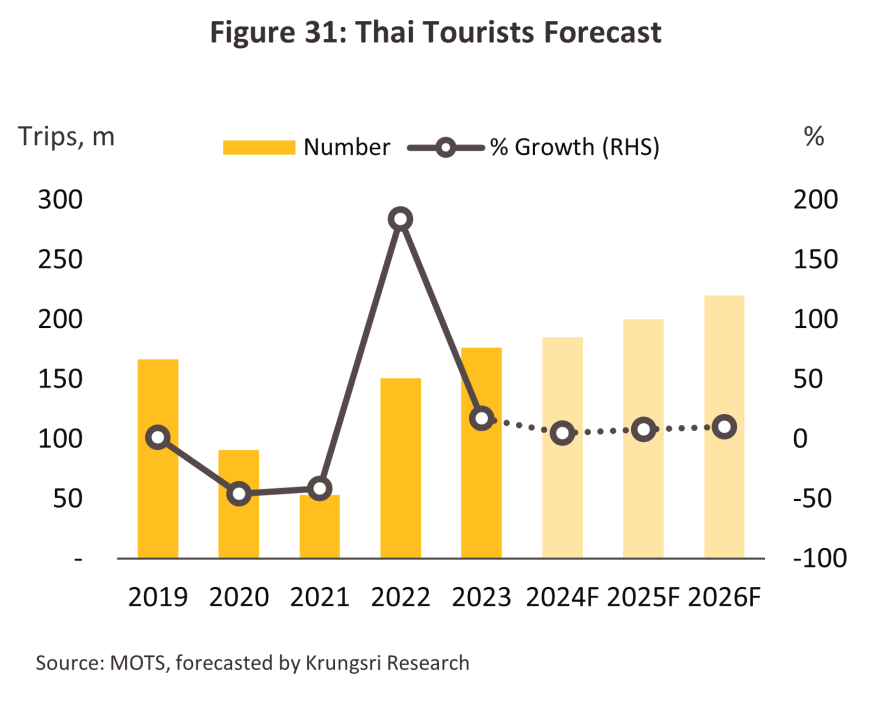

The domestic market will expand steadily over 2024-2026, with Thai tourists forecast to make 185 million trips in 2024 (during 2M24, number of Thai tourists rose 7.4% YoY to 33.9 million trips), 200 million trips in 2025, and 220 million trips in 2026 (Figure 31). Growth will be driven by the following.

1) Measures to stimulate the domestic market will continue to run. The most recent of these is the Easy E-Receipt8/, which allowed individuals staying in hotels to set their expenses (e.g., for food and accommodation) against their tax up to a maximum value of THB 50,000. Initially, the scheme ran from January 1 to February 15, 2024.

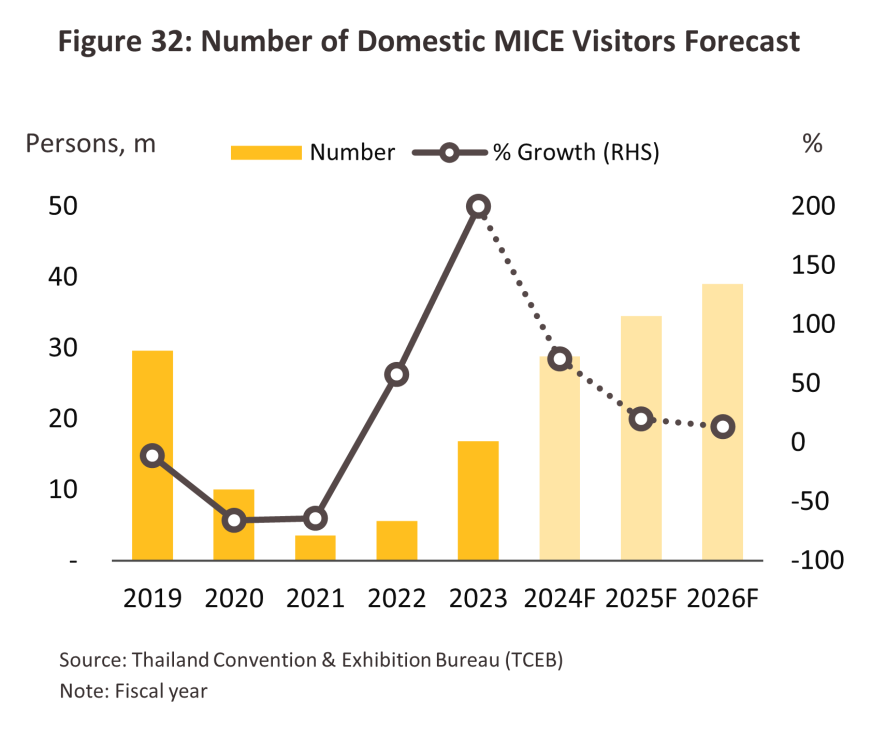

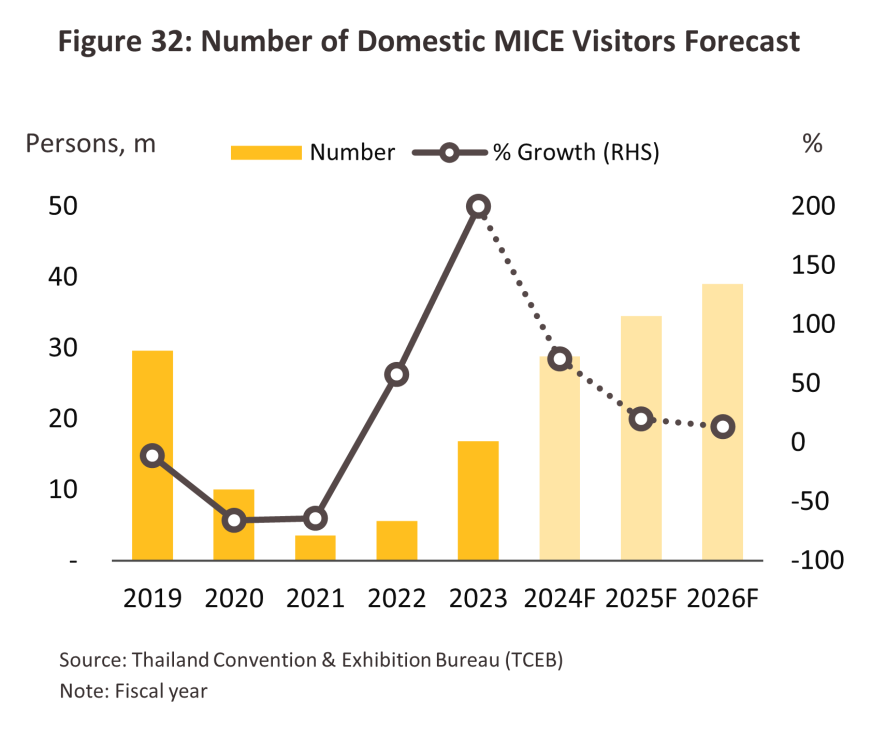

2) Both the public and private sector sides of the MICE (Meeting, Incentive, Convention, and Exhibition) market will continue to expand as the pandemic fades from view, and this will develop into major tourist areas across the country (Figure 32).

3) Development of national infrastructure will provide an additional boost to the tourism market. For example, the upgrade and expansion of airports in major tourist destinations and second-tier provinces and the extension of road and rail transport networks will help to encourage travel to currently less favored parts of the country.

-

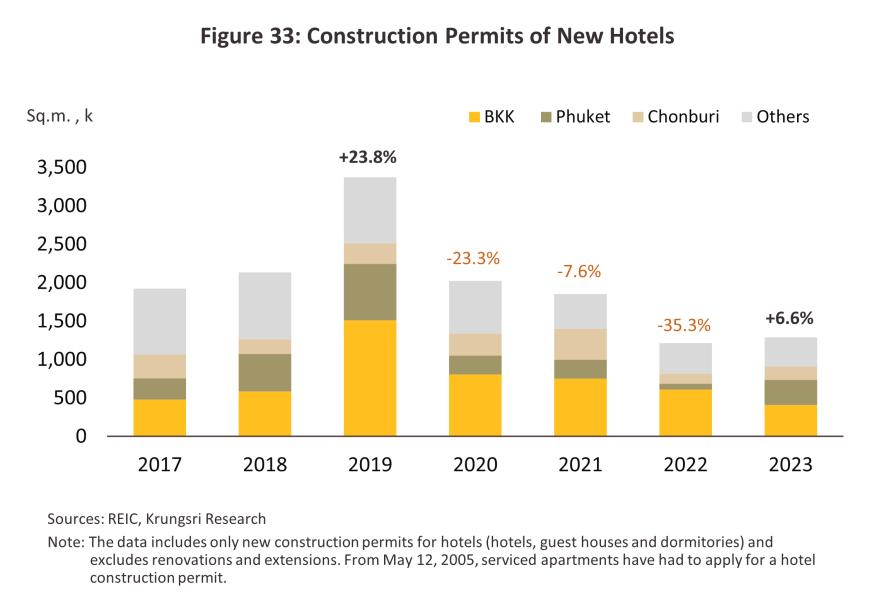

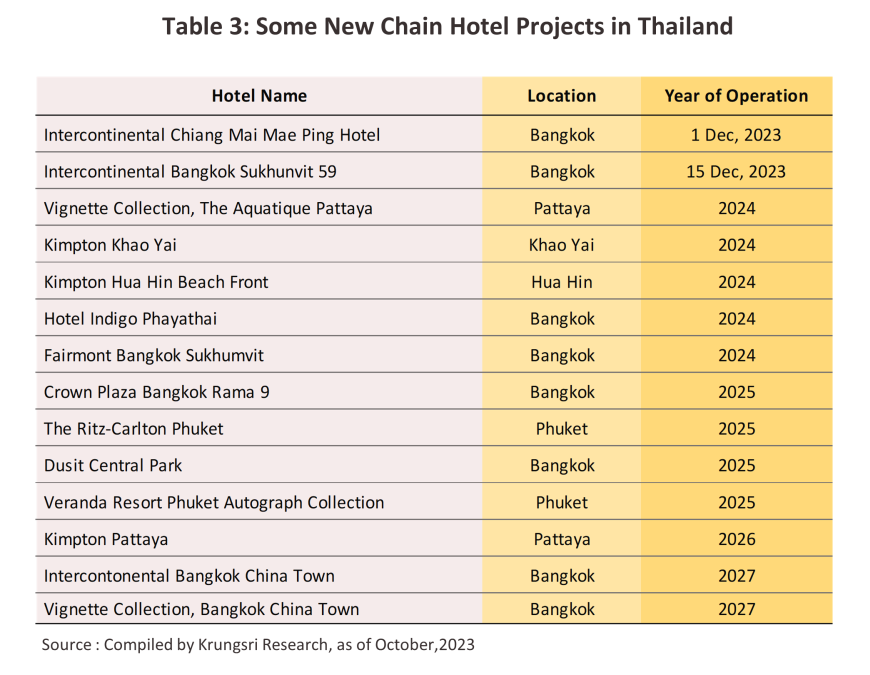

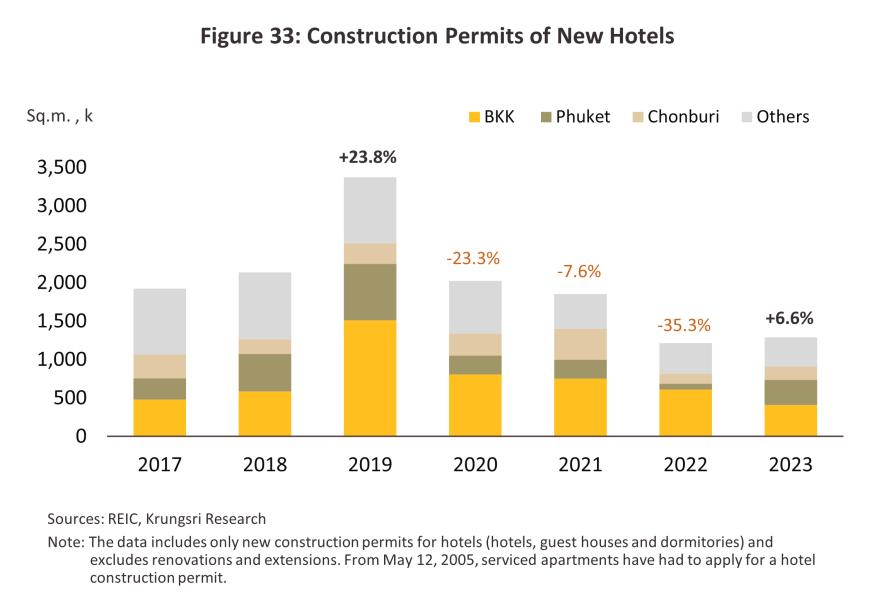

Having slowed during the pandemic, growth in the national supply of new hotel rooms is recovering, and this is now showing up in applications for hotel construction permits (these indicate changes in supply 1-2 years out). Thus, in 2023, the total footprint of these applications expanded 6.6% to 1.3 million sq.m., though this followed a period of turbulence, with applications jumping by more than 50% in 2019 but then contracting for the next 3 years under the impact of the pandemic (Figure 33). In Chonburi (14% of applications by area), these are up 39.7%, though this follows a -68.2% crash in applications in 2022, in Phuket (25% of the total), they jumped 341.8% on a mixture of comparison with the low baseline and recovery in the tourism market, and in other tourist areas and regional centers, applications are also up. Thus, these have increased 182.6% in Chiang Mai, 141.1% in Songkhla, 21.1% in Nakhon Ratchasima, and 12.7% in Prachuap Kiri Khan. By contrast, applications in Bangkok (32% of the total) are down -33.4% to 0.41 million sq.m.

-

Average occupancy rates across the country will increase through 2024 to 2026, rising above 70% from 2024 onwards (Figure 34). In the most important areas of Bangkok, Chonburi and Phuket, the occupancy rate will run above the national average thanks to the rapid recovery in overseas arrivals, while in regional centers and other tourist areas, the rate will rise on growth in the domestic market. During 2M24, the occupancy rate averaged 77.0%, up from 47.9% in 2M23.

1) Geopolitical tensions and international conflict may impact global travel. Most notably, this includes fighting between Hamas and Israel in the Gaza Strip, which may reduce outbound tourism from the Middle East, the ongoing war in Ukraine, although movement on the front is limited, and ongoing tensions between the US and China over Taiwan, which may develop in uncertain ways. If these problems drag on, this may weigh on the global economy and overseas arrivals. In particular, if crude prices rise, this will add to travel costs, impacting the market for long-haul travel from Europe and the US.

2) If the Chinese economy remains sluggish, Chinese tourists may choose to travel domestically. Worries about the safety of travel in Thailand are also a potential block on growth in the market since as elsewhere in East Asia, concerns over safety feature prominently in decisions about where to travel.

3) Domestic tourists will tend to remain wary about spending on travel and tourism, given its continuing high costs and the ongoing effects on spending power of the high burden of household debt.

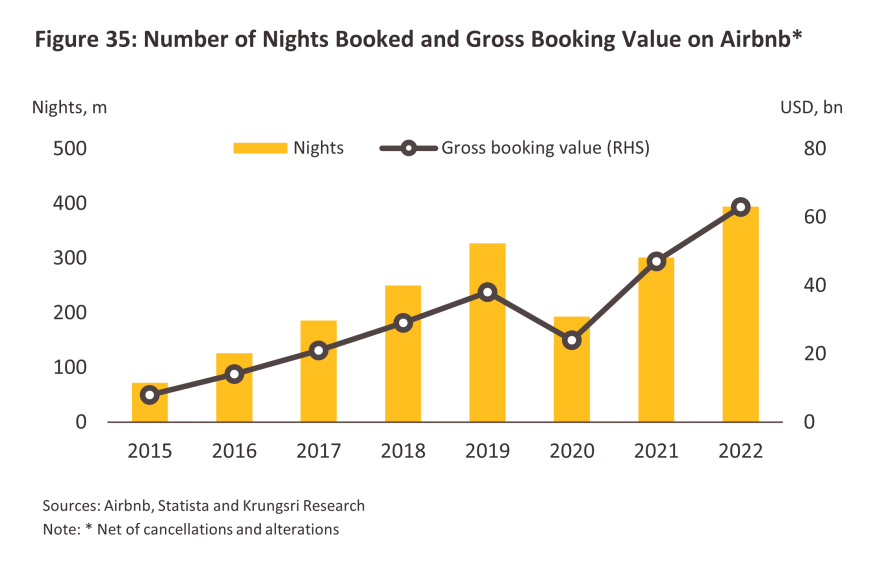

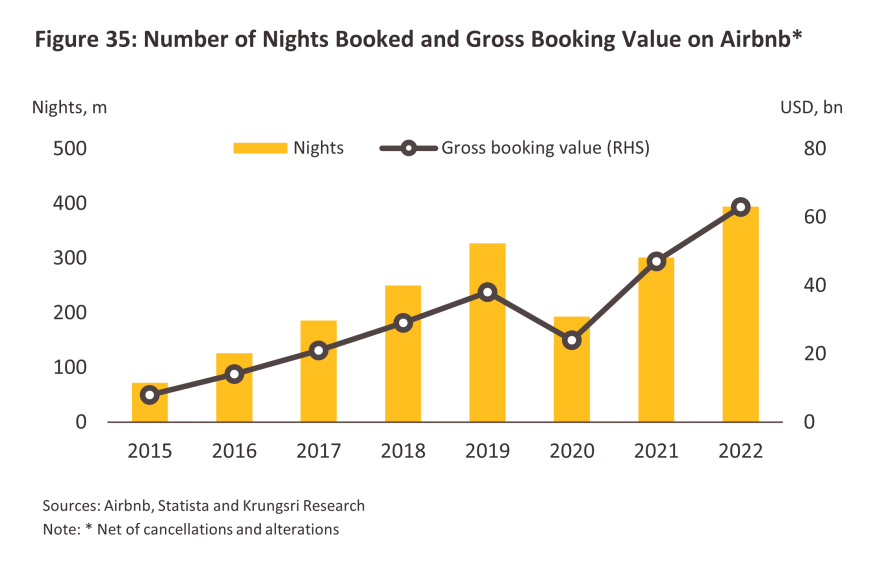

1) Competition from other hotels will intensify as a result of investments continuing to flow into major tourist areas and regional centers. This is coming both in the form of investments made by hotel operators themselves and those made by players who then bring in a hotel management team from outside to run the hotel (generally from large players that are part of extended commercial groups or that have their own chains). Hotels also have to contend with growing competition from companies such as Airbnb, which are increasingly penetrating the market for short-term accommodation. In 2022, Airbnb bookings rose above their pre-pandemic level (Figure 35), and in 2023, Bangkok made it into the 5 most popular destinations on Airbnb (Airbnb, March 2023). Although this is illegal under the 2004 Hotel Act, competition is also coming from parallel services such as regular and serviced apartments and condominiums that are rented out by the day, generally with room rates and tax bills that undercut those of hotels.

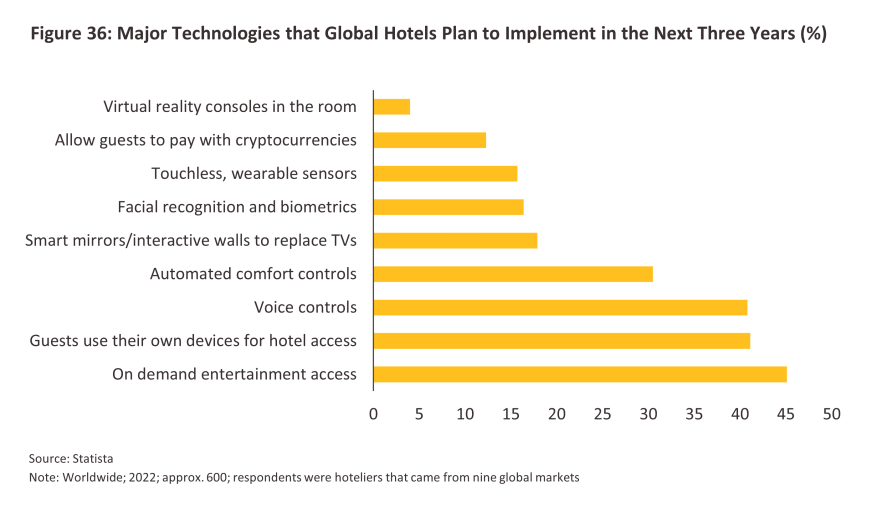

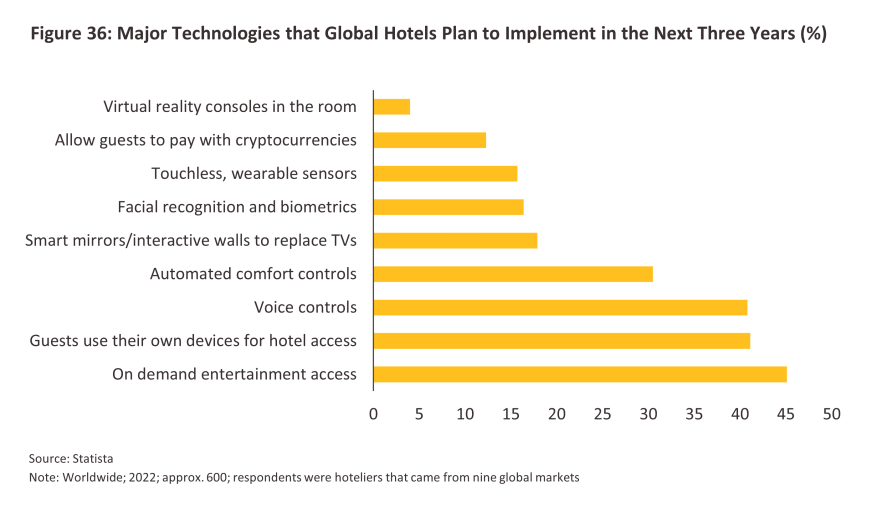

2) Competition over the use of modern technology will increase, especially among major operators, and by upgrading their services to ‘smart hotels’, players will be better placed to respond to varied and diverse consumer needs. This might include making life easier for visitors by allowing them to use technology to remotely control equipment and fittings in their room, for example by using internet-enabled devices that can be manipulated via a smartphone. This would be attractive to many visitors, especially younger guests who use their smartphone as a central tool for interacting with the world. This could then be extended to allow visitors to use their phone to check in and make payments (thus avoiding the need to contact staff at the main counter), to control heating and lighting, and to gain access to their room (i.e., by using their phone as a key) (Figure 36). On the downside, this would naturally put additional pressure on operators’ costs.

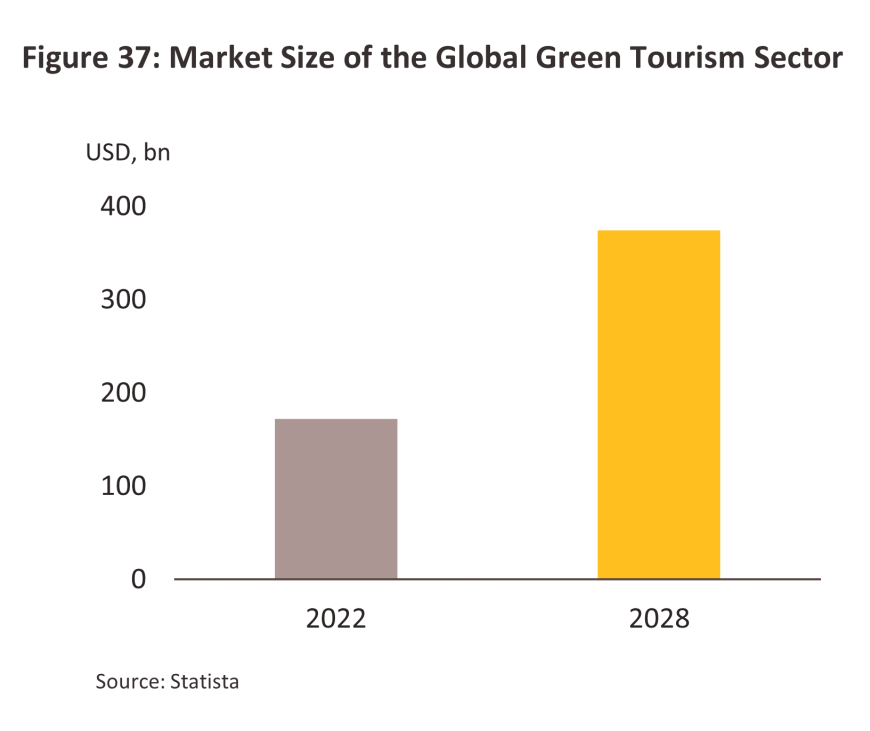

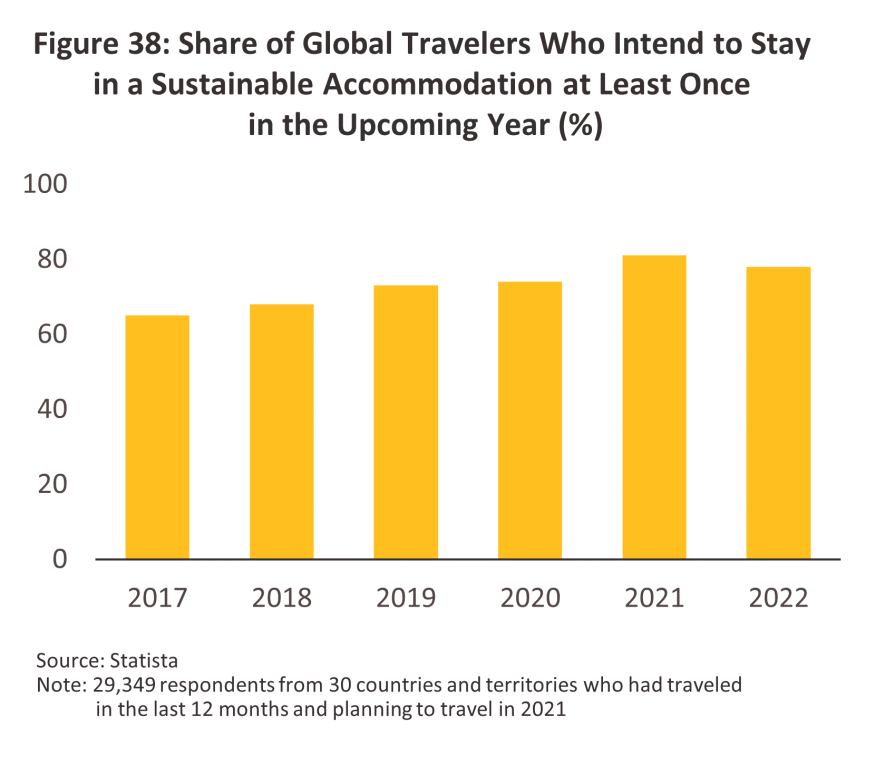

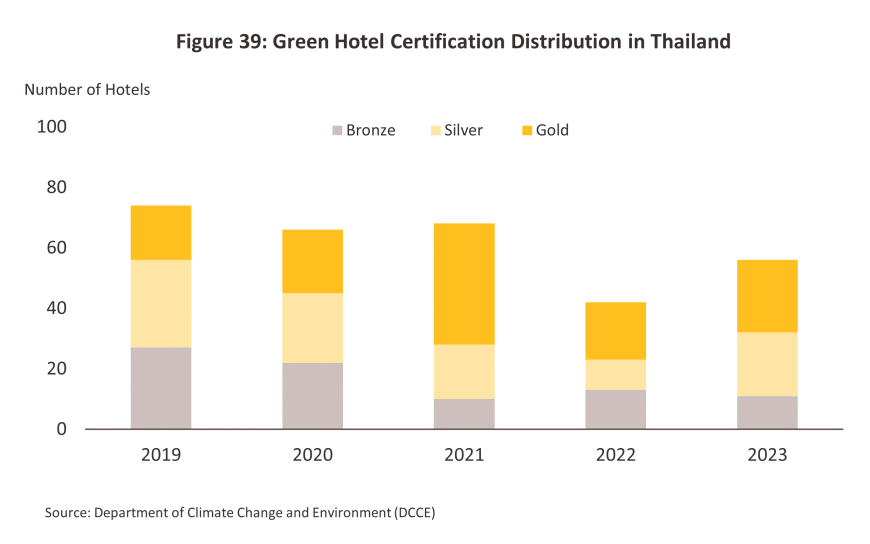

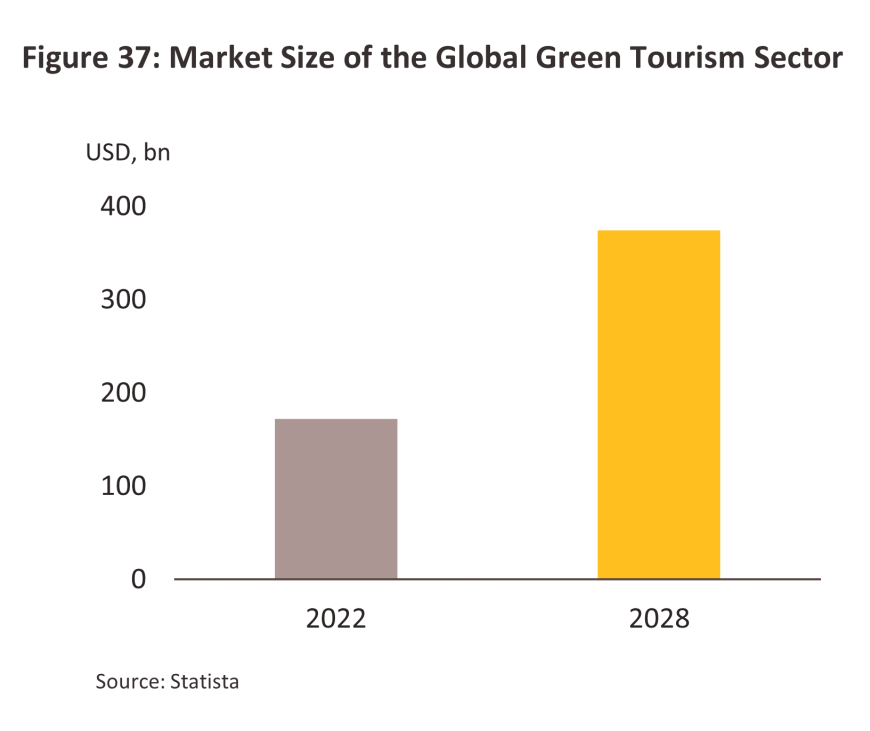

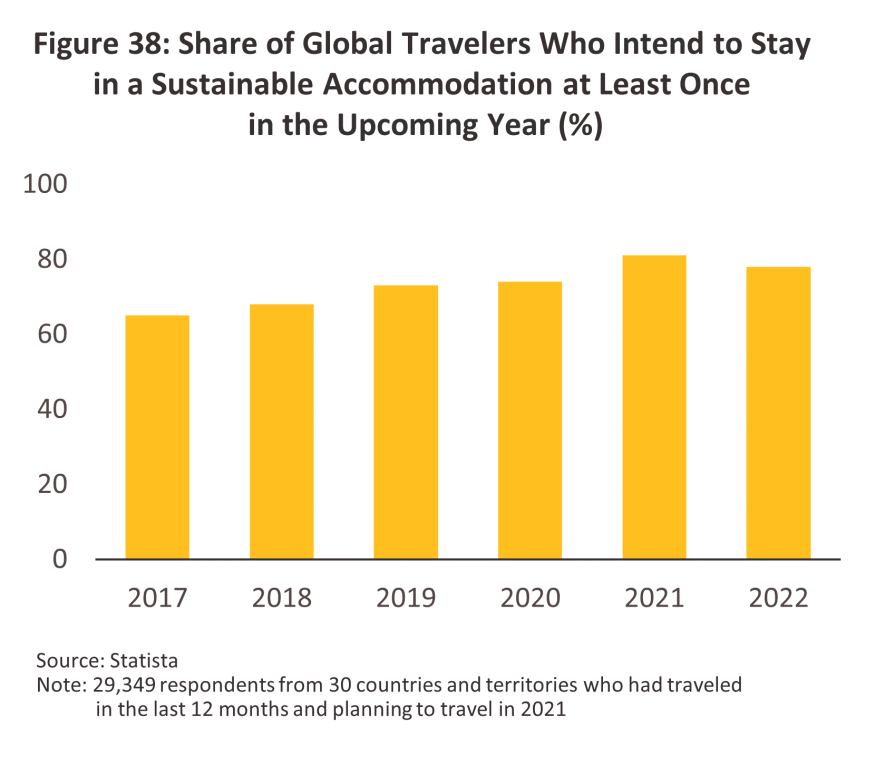

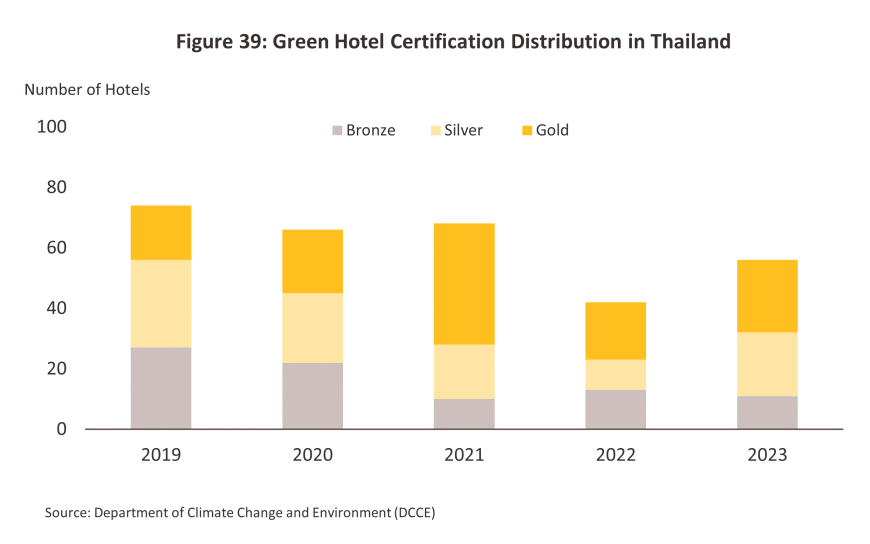

3) Business strategies that are increasingly focusing on reaching sustainability goals will likely add to overheads and investment costs. In particular, spending on the development of green hotels9/ will rise. The importance of this segment is underlined by a report by Statista that shows that globally, the value of the market for green tourism will rise from USD 172.4 billion in 2022 to an expected USD 374.2 billion by 2028, thus showing compound annual growth rate of 13.9% (Figure 37). Moreover, a 2022 survey by Statista revealed that 78% of respondents intended to stay at least once in an environmentally friendly hotel in the next year, up from 65% in 2017 (Figure 38). Thailand has in fact been running a green hotel accreditation scheme for some time. This sets standards for solid and liquid waste management, energy usage, ambient air quality and noise levels. As of 2023, 56 sites had been accredited as ‘green hotels’ in Thailand, up from 42 in 2022 (Figure 39).

4) Safety regulations governing the provision of accommodation services have been tightened, including the rules covering the safety systems that are required in hotels. These changes are necessary because a wide range of building types are now used to provide hotel services, and buildings not originally built as hotels are increasingly used as these. (These changes by the Ministry of Interior were published in the Royal Gazette on 30 August 2023, and came into effect 60 days after this). These new rules will make it easier for other types of commercial buildings to be adapted and used to provide hotel services, unlike in the past when this was not allowed, and this will likely increase costs and add to competition on the supply side of the market.

1/ Chiang Mai, Chiang Rai, Phitsanulok, Kanchanaburi, Rayong, Chachoengsao, Nakhon Ratchasima, Khon Kaen, Udon Thani, Ubon Ratchathani, Phetchaburi, Prachuap Kiri Khan, Songkhla, Krabi, Phang-gna and Surat Thani (Ko Samui).

2/ In November 1983, the Chinese government first allowed Chinese citizens to travel abroad, initially permitting travel to Hong Kong and Macau for those visiting family members. The process of travel liberalization was accelerated by China’s entry to the WTO in 2001 and the requirement that China operate under WTO regulations regarding tourism. The result of this has then been to dramatically increase the number of Chinese tourists traveling abroad (Bank of Thailand, June 2014).

3/ Hoteliers typically consider an occupancy rate of 65-70% satisfactory (source: interviews with hotel operators and analysis of data from the Bank of Thailand)

4/ These include: (i) the World’s Best City Award 2013, presented by Travel & Leisure magazine to Bangkok for the 4 years from 2010 onwards; (ii) the Business Traveller Asia-Pacific Awards 2022, with Bangkok voted the ‘Best Leisure City in the Asia-Pacific’ for 6 years running by Business Traveller Asia-Pacific readers; and (iii) the 2022 Most Improved Award for MICE destinations, awarded by the Global Destination Sustainability Index (GDS-Index).

5/ These include Thailand, Indonesia, Cambodia, the Maldives, Sri Lanka, the Philippines, Malaysia, Singapore, Lao PDR, the UAE, Egypt, Kenya, South Africa, Russia, Switzerland, Hungary, New Zealand, Fiji, Cuba, and Argentina.

6/ Data gathered from the 6 airports operated by Airports of Thailand (Suvarnabhumi, Don Muang, Chiang Mai, Mae Fah Luang, Had Yai, and Phuket).

7/ In 2023, 172,000 Kazakhs visited Thailand (up from 59,000 in 2022), making this the second most important Central/Eastern European market after Russia. These tourists are also relatively high spending, with the average daily spend coming to THB 75,000/person/day compared to the average of THB 48,000/person/day for overseas tourists (as of 2019).

8/ This applies only to full e-tax invoices and e-receipts issued by the Revenue Department. Goods and services excluded from the scheme include: (i) spirits, wine and beer; (ii) tobacco products; (iii) autos, motorcycles, and boats; (iv) transport fuels; (v) utility bills (e.g., for electricity, water, and telephone and internet services); (vi) insurance; and (vii) agreements to provide services outside the period of the scheme.

.webp.aspx)