EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Over the next three years, domestic economic growth will translate into rising investment in the manufacturing sector, and this will in turn herald an improving outlook for operators of industrial estates. The total footprint of land sold and leased on industrial estates is therefore expected to surge by 18.0-20.0% annually over 2023-2025 to 2,200, 2,700, and 3,000 rai (1 rai = 0.16 hectares) in each of these years. Several factors will combine to support the industry in the coming period. (1) Spending by the government on infrastructure will accelerate over the next few years, especially in the EEC, where the implementation of phase 2 of the EEC development plan over 2023-2027 will have noticeable effects in 2024 and 2025. This will then help to crowd in additional private-sector investment in the area. (2) The fading of the COVID-19 pandemic is helping to revive investor sentiment. (3) Some foreign companies are looking to move production facilities to Thailand and/or to expand sites already operating in the country. This is partly being driven by the wish to dodge risk arising from worsening US-China trade and geopolitical tensions. (4) Government investment promotion schemes will continue to operate and to have an effect on investment decisions. Operators of industrial estates will tend to move their sites towards becoming ‘smart parks’ that are equipped with modern production technology, transportation and logistics systems, and energy supplies, and to develop their estates in a more environmentally friendly direction. This will then help them move in step with the thrust of government policy, which aims to shift the country towards the adoption of the BCG (Bioeconomy, Circular Economy, and Green Economy) model. Players will also look to build long-term sustainable growth by developing partnerships with businesses operating in other sectors of the economy, such as providrs of utilities and logistics services.

Krungsri Research view

In 2023-2025, the industrial estate outlook is likely to recover in line with investment expansion in manufacturing. Such recovery would bolster earnings arising from sales and leases of land. However, the revenue of operators would be different relying on the growth prospect of industrial estates located in each area.

-

Industrial estates in the eastern region: Income will tend to rise at a sharper rate for operators in the eastern region than for those in other areas, with this driven by strong growth in demand for space to rent or lease. The market will be boosted by government spending on infrastructure construction that will support the development of the EEC (Chonburi, Rayong, and Chachoengsao). This will then serve to attract greater interest from domestic and international investors, especially for those active in industries that are targeted for support by the Thai government. However, in the coming period, the supply of new space on industrial estates (both new developments and extensions to existing estates) tends to be limited due to steadily rising land prices and the increasing difficulty that developers are having in finding suitable new locations.

-

Industrial estates in the central region: Income will tend to grow solidly for players in this group, especially from rents and charges for the supply of services and utilities. This is due to the advantages the central region has in terms of access to logistics networks. However, growth in the supply of space on industrial estates will again be limited, though in this case this will arise from the concentration of suitable sites in Bangkok, Samut Prakan, Ayutthaya, and Saraburi.

-

Industrial estates in other regions: Income will tend to remain flat due to low demand in these areas. Local markets for industrial space continue to wait for more concrete government action, especially for progress on infrastructure projects such as transport and logistics networks that link these areas to nearby regions and on to neighboring countries. However, in the absence of this, growth in the market for space on industrial estates outside the central and eastern regions will continue to be relatively sluggish.

Overview

Industrial estates is the business to prepare land for lease to or purchase by industrial and commercial operators. Providers of industrial estate services also supply businesses located on these sites with access to amenities and utilities such as electricity, water, flood defenses, and centralized sewage services.

Within Thailand, industrial estates come under the oversight of the Industrial Estate Authority of Thailand (IEAT), which manages both: 1) industrial estates that the IEAT owns and operates alone, and 2) industrial estates that the IEAT owns and operates in partnership with private sector players. In addition to industrial estates, industrial parks, and industrial zones also exist and broadly speaking, these share many of the characteristics of industrial estates, though these are privately owned and run[1]. These come under the control of the Board of Investment (BOI), which has assigned their regulation to Department of Industrial Works provincial offices.

Income for these businesses comes from two principal sources: (1) the leasing and sale of land; and (2) income from other services, for example, the leasing of factories and warehouses and the supply of utilities (e.g., water and electricity). The latter is a form of recurring income, and this then helps to reduce players’ exposure to the risk of the fluctuations in turnover that would otherwise arise from relying on the sale of land alone (the income streams of two major players are shown in Figure 1).

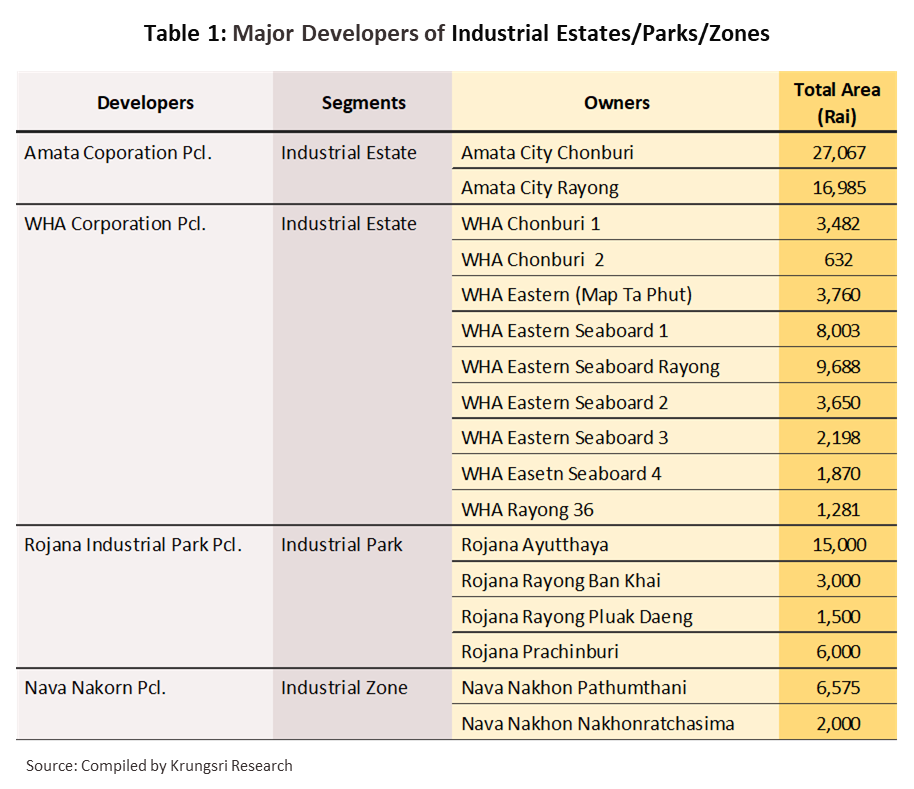

Businesses usually prefer to move onto sites on industrial estates rather than build from scratch on empty land, because the former are already equipped with the requisite infrastructure, utilities, and transportation links. Establishing operations on industrial estates may also benefit companies financially, since if they do this, they may qualify for incentives provided by the government in the form of tax relief or other forms of investment support. The two major operators of industrial estates in Thailand are Amata Corporation and WHA Group, while Rojana Industrial Park and Navanakorn are the most important operators of industrial parks and industrial zones.

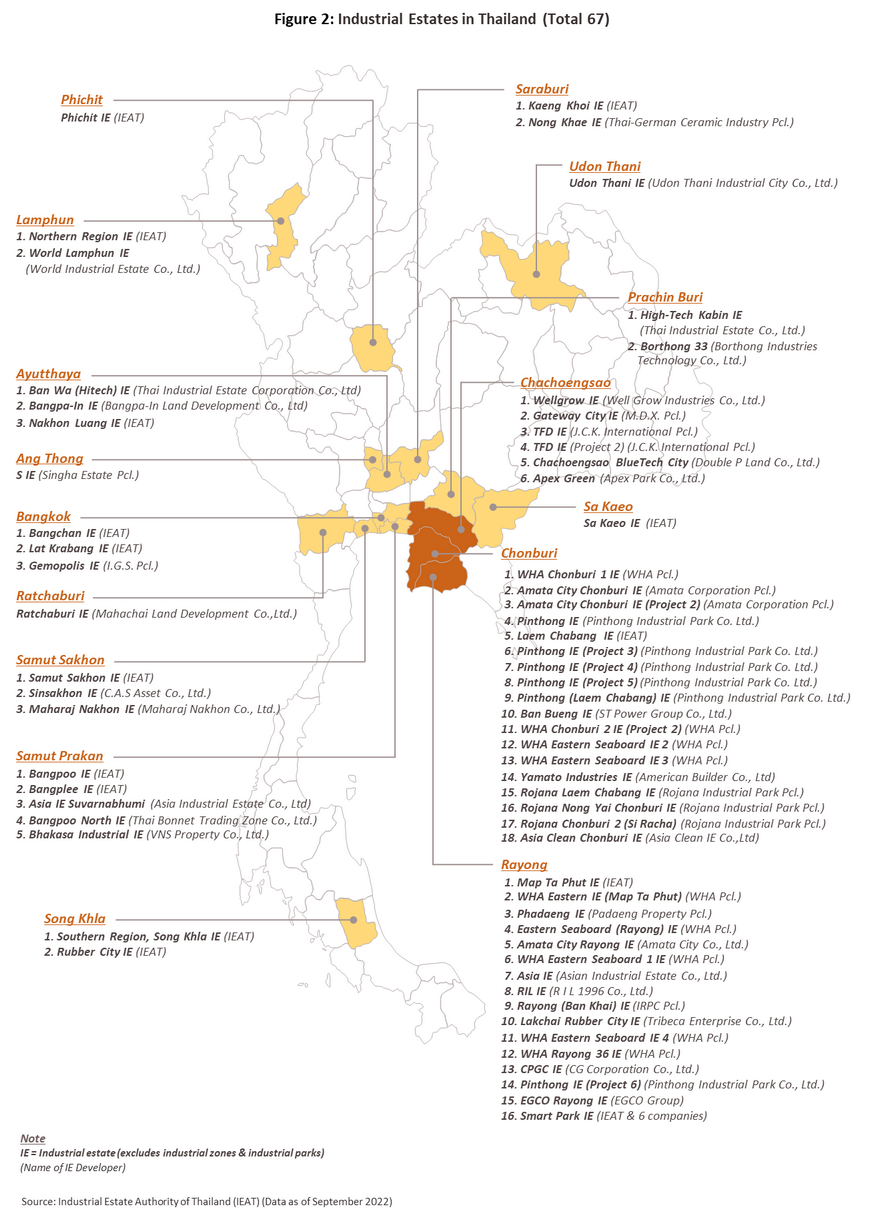

The most important factors influencing the growth of demand for industrial estates are: (1) the state of the domestic and international economies and local political conditions; (2) multinational companies’ approach to investing and establishing production facilities in Thailand; (3) the physical and geographical conditions of the country; and (4) the extent to which government rules and regulations support investment in the domestic industry sectors, and the level of incentives that the government provides for investors in the industrial estates. As of September 2022, there were 67 industrial estates in Thailand, spread across 16 different provinces (Figure 2) and covering a total area of 169,823 rai, or up 0.9% from 2021’s total of 168,354 rai. Of this total, 14 sites were operated by the IEAT alone and the remaining 53 were joint ventures with the private sector. The eastern region houses the vast majority of the country’s industrial estates (Figure 3), with 77.8% of the total (132,084 rai), followed in importance by the central area (including the Bangkok Metropolitan Region), which contains another 16.0% of the total. As of 9M22, 132,083 rai of land on industrial estates had been sold or leased, giving an occupancy rate of 77.8%, up very slightly from 2021’s 76.9% (Figure 4). In terms of investors’ origins, Japanese operators are by investment value the most important overseas players active on industrial estates, followed by those from China and the US (Figure 5), while by industry, the biggest share of land is occupied by players from the automotive and transport industries (Figure 6).

The growth potential of the industry varies from area to area across the country and so details for individual regions are given below.

-

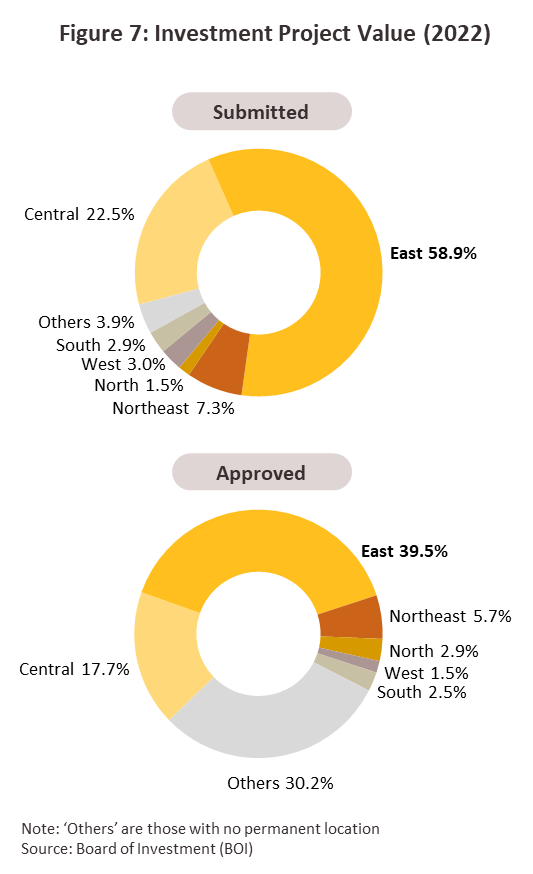

The eastern region: This area, which extends over the provinces of Chonburi, Rayong, Chachoengsao, Prachinburi, and Sa Kaeo, has the greatest potential for growth since it is home to the Eastern Seaboard Development Program. Businesses are well served by the area’s transport and logistics networks, which include convenient road transport connections, airlinks (Suvarnabhumi and U-Tapao airports are nearby), and easy access to commercial shipping (Laem Chabang and Map Ta Phut seaports are in the same area). Bangkok is also nearby and easily accessible. In addition, the area is dense with industrial activity, including oil refining and petrochemicals, chemicals, auto assembly and auto parts manufacturing, electronics, and food processing, and as such, the government has provided ongoing support to the development of manufacturing within the region. The outcome of this has then been that not only does the eastern region have the greatest concentration of industrial estates in the country, but it also continues to attract the most interest from investors, which is then reflected in the disproportionately large share of applications to the BOI for investment support for projects sited in the area (Figure 7).

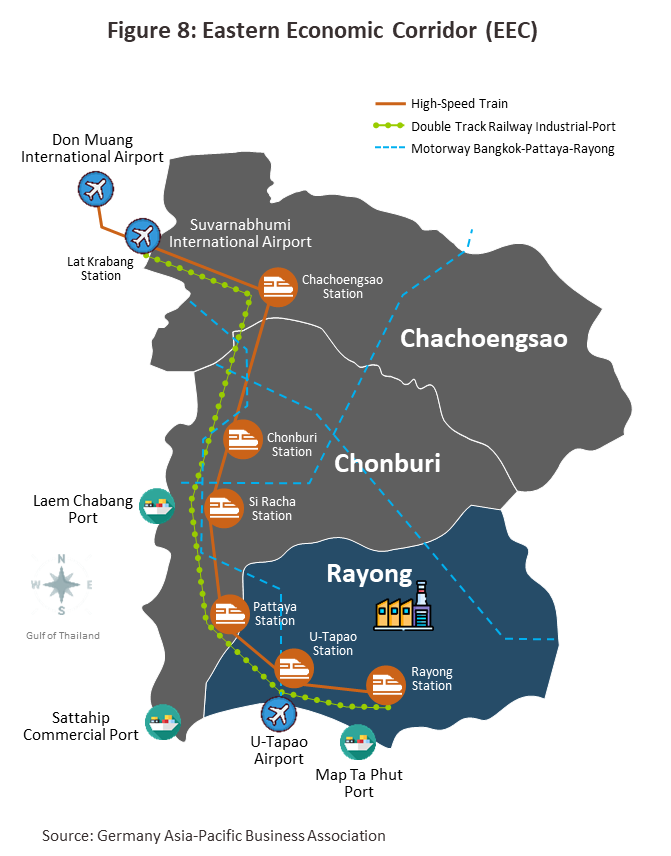

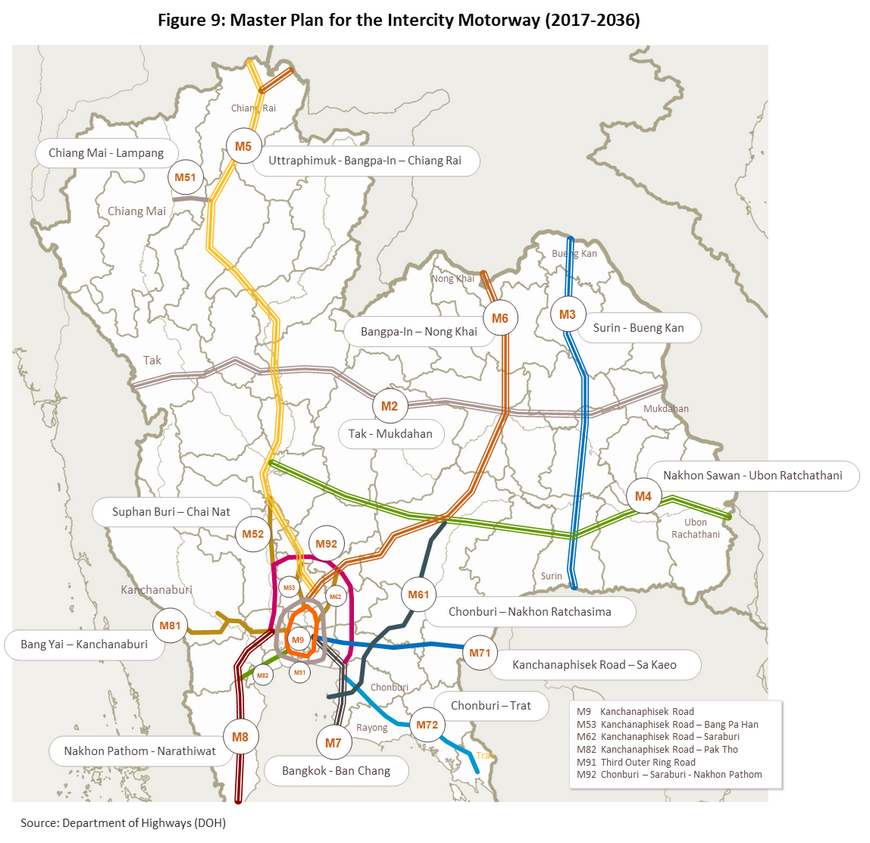

- In addition, Chonburi, Rayong, and Chachoengsao have been designated as home to the Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC) development (Figure 8). This area has been chosen for this strategically important development thanks to the provision of infrastructure in these provinces enabling the private-sector players can move straight in and begin operations almost without delay. The government is especially hoping that investment will be forthcoming in its twelve targeted industries[2], all of which are technology- and capital-intensive. This hope is underpinned by government spending on infrastructure megaprojects that are helping to strengthen the area’s transport and logistics networks and so increase its appeal. In order to attract investment from domestic and international sources, the government is thus working on the development of infrastructure including (1) the high-speed rail link connecting the area’s 3 airports; (2) U-Tapao International Airport; (3) the intercity motorway; (4) the dual-track railway; (5) phase 3 of Laem Chabang Port; and (6) phase 3 of Map Ta Phut Industrial Port.

-

The central region: This area benefits from being a center of manufacturing and the focus of the national transport and logistics networks. The central region includes Bangkok itself, which is home to per unit the most expensive industrial land in the country, together with provinces that are home to important industrial estates, including Samut Prakan, Ayutthaya, Saraburi, Samut Sakhon, and Ang Thong. Auto parts, electrical appliance, and electronics manufacturers are concentrated in the area, in addition to industries that utilize local resources, such as food processing and construction materials, together with a large number of factories operated by SMEs. However, industrial estates in the area were badly affected by the extensive flooding in October and November 2011, and this had a marked impact on sales and leases. Following this low, the situation improved somewhat from 2014 onwards, and this recovery helps to illustrate the continuing ability of industrial estates in the central part of the country to attract interest from investors.

-

The northern and northeastern regions: Generally, industrial estates in these areas host food processing industries together with some electronics manufacturers, but transport and logistics links are inferior to those in other parts of the country, and this has tended to curb interest. However, progress on developing road (Figure 9) and rail links in the north and northeast that will connect Thailand to its neighbors (i.e., the 323 kilometer stretch of dual-track railway from Den Chai to Chiang Rai to Chiang Khong in the North and the 355 kilometers of the dual-track railway from Ban Phai to Nakhon Phanom in the Northeast) and then on to China and Vietnam should help to stimulate future investment. At present, industrial estates are located in the northeastern province of Udon Thani and in the northern provinces of Lamphun and Phichit.

-

The western region: This area is largely still awaiting development. The Industrial Estate Authority of Thailand had planned to develop a new industrial estate to support and connect to the proposed industrial zone and deep-water port in Dawei, Myanmar, but the importance of the latter has slipped and the authorities in Myanmar are instead now focusing on the development of an industrial area in the Thilawa special economic zone. Given this, the impetus for investing in industrial estates in the western region has slackened, though at present, one industrial estate in Ratchaburi is active.

-

The southern region: This region is being developed with the goal of improving connections between the south of Thailand and Malaysia. The area’s major industry is rubber cultivation and its downstream industries, but at present, the South is host to only a single industrial estate in Songkhla. In 2016, the IEAT decided to halt development of a new industrial estate in Pattani province planned for producers of halal food since interest from major operators, both Thai and international, was lacking. Unfortunately, the ongoing disturbances in the deep South and subsequent fears over security combined with an insufficient local supply of electricity have meant that the development of industrial estates in the South has not proceeded as might have been hoped.

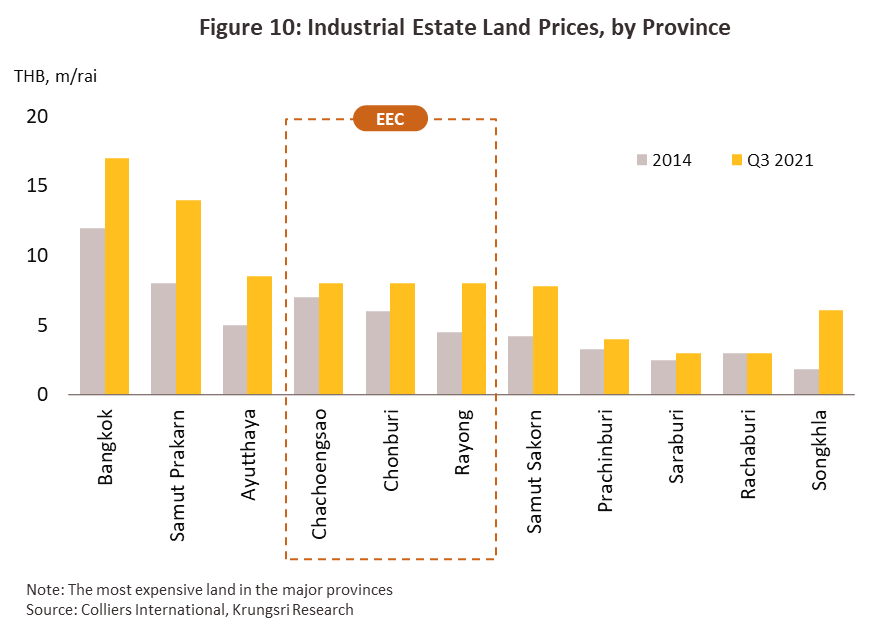

The cost of land (for both leasing and purchase) in industrial estates varies from one site to the next and depends on factors including (1) location, (2) the provision of utilities, (3) access to logistics and transportation links, and (4) access to raw materials or industrial inputs (Figure 10). Bangkok’s position in the center of the country’s land, water, and air travel networks means that land on industrial estates in the Bangkok Metropolitan Region is the most expensive in the country. This also tends to lift prices in adjacent areas, so industrial estate land prices are high in areas such as Samut Prakan too. Space in the EEC (in the provinces of Chonburi, Rayong and Chachoengsao) is the second most expensive in the country and as of 3Q21, prices in the three provinces of the EEC had risen to a high of THB 8 million/rai (THB 1.28 million/ha), a roughly 40% rise on the THB 5.8 million/rai (THB 0.93 million/ha) recorded in 2014 prior to the start of wider government efforts to promote the EEC (source: Colliers International).

Situation

In 2021, the industrial estates industry recovered somewhat from the depressed conditions of a year earlier. As elsewhere in the economy, the need to battle the spread of COVID-19 through the imposition of strict controls had significant consequences, and in this case, 2020’s uncertain economic conditions encouraged investors to postpone decisions to purchase or lease land on industrial estates. However, the move by the authorities to relax controls and to begin to allow foreign visitors to return to Thailand in the second half of 2021 helped to kickstart the revival of the industry.

In the first 9 months of 2022, sales and leases rose, driven by the reopening of the country in mid-2022 and more progress in construction of infrastructure projects, especially in EEC.

-

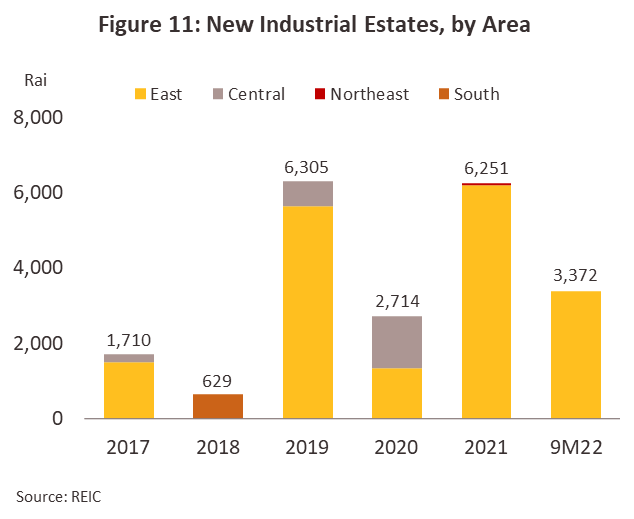

Two new industrial estates were opened in the period, both in the EEC and indeed both in Chachoengsao province (Figure 11). These were the 1,181-rai BlueTech City industrial estate and the 2,191-rai Apex Green industrial estate. The opening of these took the total tally of industrial estates to 67, and these had a combined footprint of 169,823 rai as of 9M22; 43 industrial estates were operating in the eastern region, giving it by far the largest share of the total.

-

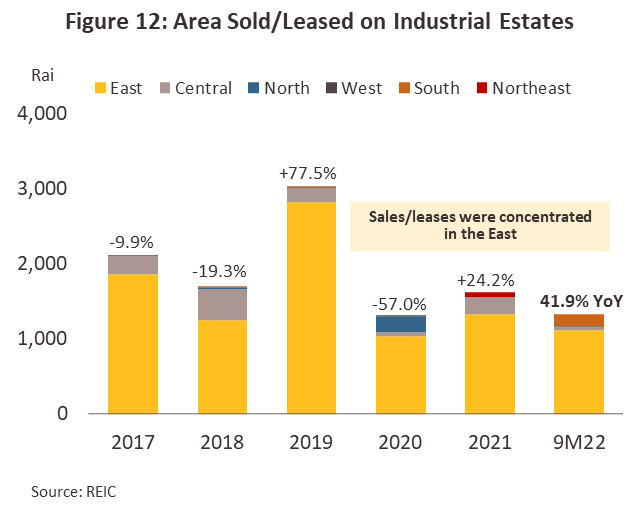

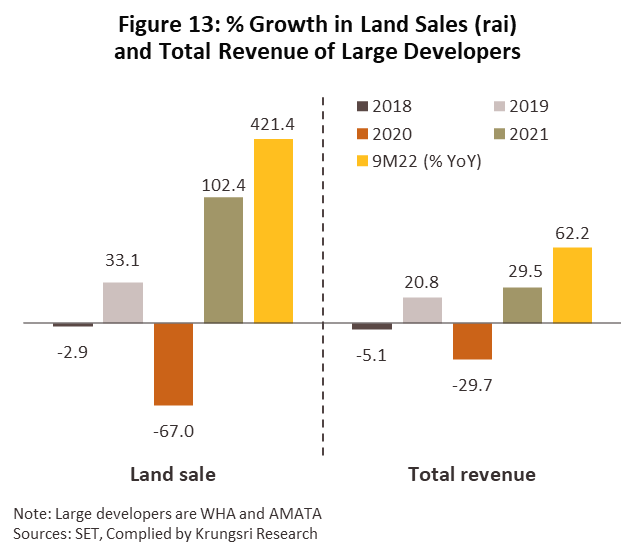

New sales and leases surged 41.9% YoY to 1,354 rai in 9M22 (Figure 12). Those were overwhelmingly concentrated in the eastern region, and this area accounted for 83% of the business (1,121 rai) in the period. This was followed in importance by the southern (159 rai) and central (37 rai) regions. This then brought the total space occupied on industrial estates to 132,083 rai, giving an occupancy rate of 77.8% (up marginally from 9M22’s rate of 76.9%). With the improving investment situation, the two biggest players in the industry (AMATA and WHA Group) are investing in technology to upgrade their sites to ‘smart industrial estates’ and expanding their offerings to include a much more comprehensive range of utilities and services. This has helped to boost receipts, and thus these two players saw their joint income surge 62.2% YoY (Figure 13).

-

The value of investment projects approved for BOI investment support nationwide jumped 20.8% to THB 620 billion in 2022. Of this, THB 220 billion (36%) was for investments in the EEC, which were up 16.9%. However, with the exception of the Northeast where the value of BOI-approved projects surged 301.6% to THB 35 billion, across the rest of the country, the value of investments approved for BOI assistance slipped.

-

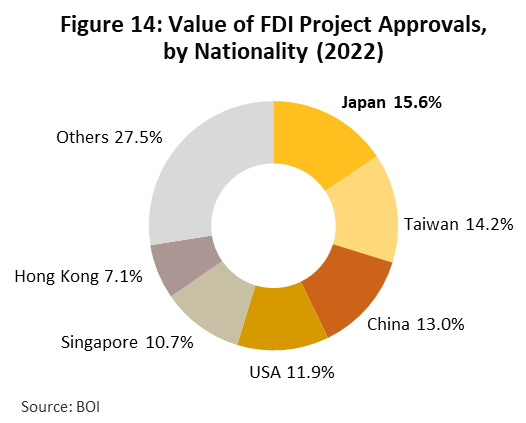

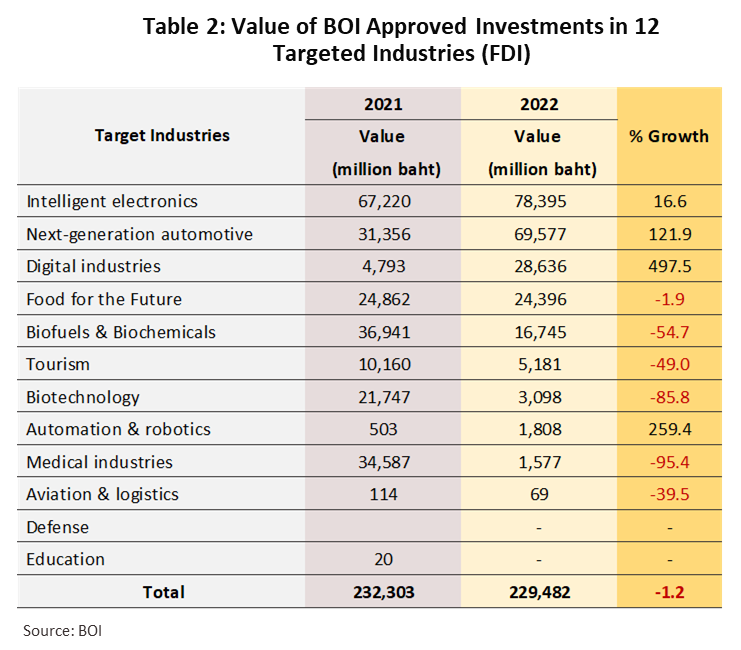

In 2022, the value of investment project approved for BOI support received from overseas investors climbed 14.4% to a total of THB 320 billion, with 72% of this total, or THB 230 billion, being for investments in the government’s target industries. Japan was the most important source of FDI, accounting for 15.6% of the total (THB 50 billion), followed by Taiwan and China (Figure 14). By value, the S-curve industries benefiting from the greatest BOI-approved investment were intelligent electronics, with THB 78 billion in inflows, and next-generation automotive industries, with another THB 69 billion (Table 2).

-

The sharp rise in the value of BOI-approved investments throughout 2022 and the full reopening of the country in July, which will allow investors to travel to the country more conveniently, combined to support an increase in the sale and lease of sites through the second half of the year. As such, for all of 2022, these are expected to rise by 11.5% to around 1,800 rai.

Outlook

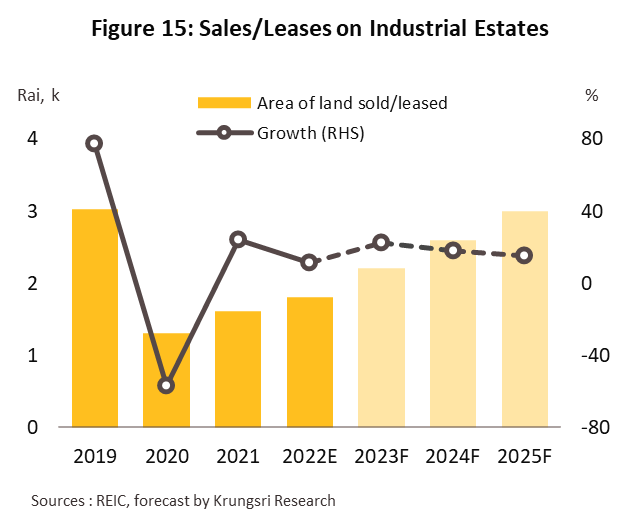

Sales and leases of land on industrial estates are forecast to rebound to growth running in the range of 18.0-20.0% per year over the next few years. This will then take the total footprint of space becoming occupied annually to 2,200, 2,700, and 3,000 rai over each of the next three years (Figure 15). This positive outlook will be supported by the following factors.

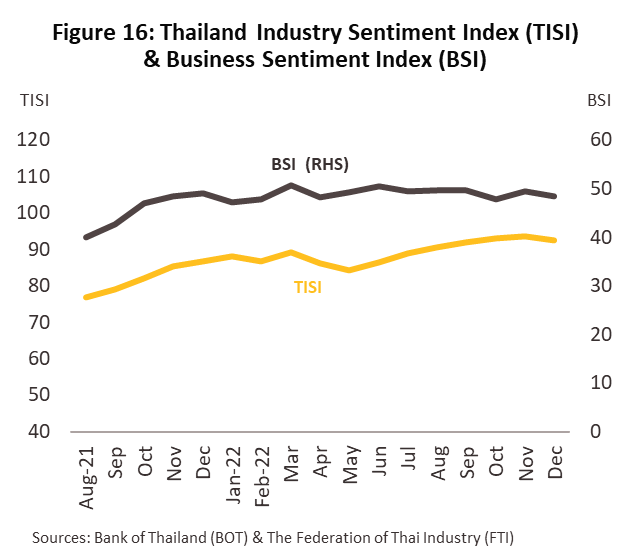

1) Sentiment will improve among foreign investors now that the COVID-19 pandemic is fading and the degree of intensity of the war between Russia and Ukraine is expected to gradually lessen. In addition, thanks to the full reopening of the country, investors are now able to come to Thailand to inspect prospective business sites in person, negotiate agreements, and sign contracts (being able to conduct an in-person assessment of a potential site and its broader environment is an important part of concluding investment decisions). Domestic confidence is also steadily strengthening on a brighter outlook for business, and so with demand building and economic activity reviving, the Thailand Industry Sentiment Index (TISI) rose 8.0% in 2022. At the same time, the Business Sentiment Index (BSI) climbed 8.1% on an improvement in confidence in both the manufacturing and non-manufacturing sides of the economy (Bank of Thailand, December 2022) (Figure 16).

2) Foreign investors will increasingly look to shift production facilities to the ASEAN zone or to expand sites already there, as they try to avoid future supply chain disruptions. These are particularly at risk from worsening tensions between China and the US over trade and with Taiwan over its future independe4) Government pro-investment measures continue to be made, including additional tax breaks for investors and liberalization of regulatory regimes. It is hoped that these changes will help to increase FDI to Thailand. Recently, such moves have included: (1) the BOI investment act extending corporate tax waivers to a maximum of 13 years (up from 8) and cutting tax by 50% for another 5 years; and (2) new BOI Long-Term Resident visa (LTR visa) that give special privileges3/ to investors and long-term residents in Thailand. These began to be issued on September 1, 2022, and the hope is that these will help to attract individuals to Thailand who have skills and expertise in modern technology, especially in the government’s 12 targeted industries.nce. In this environment, Thailand will benefit from the advantages it gains from its status as a major trade and manufacturing hub located in the heart of the ASEAN zone, advantages that are amplified by the country’s logistics capabilities and extensive road and rail connections with the broader region. This may thus be a significant driver of future investment.

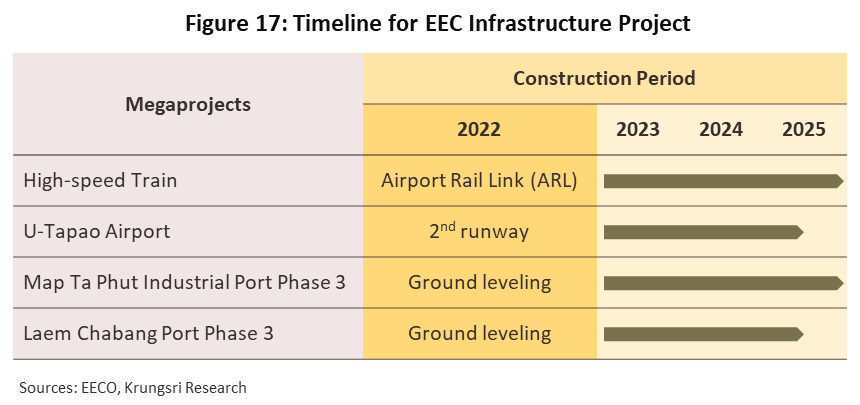

3) Spending on integrated transport infrastructure will increase, especially in the EEC where this will be boosted by the implementation of phase 2 of the EEC development plan (2023-2027). The latter will include the high-speed rail link connecting 3 airports (Don Muang – Suvarnabhumi – U-Tapao), phase 3 of the development of Map Ta Phut and Laem Chabang seaports, and the development of U-Tapao Airport (Figure 17). These projects will continue to play an important role in sustaining growth for industrial estates in the eastern region. Over the nearly 5 years covering the period from 2018 to the end of Q3 2022, inflows into the S-curve and new S-curve industries have accounted for 57% of the value of all BOI-approved investments.

4) Government pro-investment measures continue to be made, including additional tax breaks for investors and liberalization of regulatory regimes. It is hoped that these changes will help to increase FDI to Thailand. Recently, such moves have included: (1) the BOI investment act extending corporate tax waivers to a maximum of 13 years (up from 8) and cutting tax by 50% for another 5 years; and (2) new BOI Long-Term Resident visa (LTR visa) that give special privileges[3] to investors and long-term residents in Thailand. These began to be issued on September 1, 2022, and the hope is that these will help to attract individuals to Thailand who have skills and expertise in modern technology, especially in the government’s 12 targeted industries.

Players are investing in business transformation that is taking a wide range of forms, including the following:

1) To help companies maintain their competitiveness, operators are developing smart park-style industrial estates that are fitted out with modern production technology, communications and transport equipment, and power supplies. Increased investment in modern technology (e.g., online platforms) will allow manufacturing operators sited on industrial estates to make greater use of digital technology (e.g., robots and automated systems), and this will then increase their productivity and raise their competitiveness.

2) In keeping with the BCG model, industrial estates are being developed in a more environmentally friendly way. For example, the construction of the Map Ta Phut Smart Park industrial estate used greener hydraulic cement, and the estate has replaced fossil fuels with power generated from solar and bioenergy that is then managed efficiently with modern technology. The IEAT estimates that compared to older-style estates, operating the new site will result in a 70% drop in carbon-dioxide emissions.

3) Operators are partnering with other businesses to allow them to offer a more comprehensive range of support that includes transport, distribution, energy, e-commerce, and waste and refuse services. This will also help owners of industrial estates to broaden their income base.

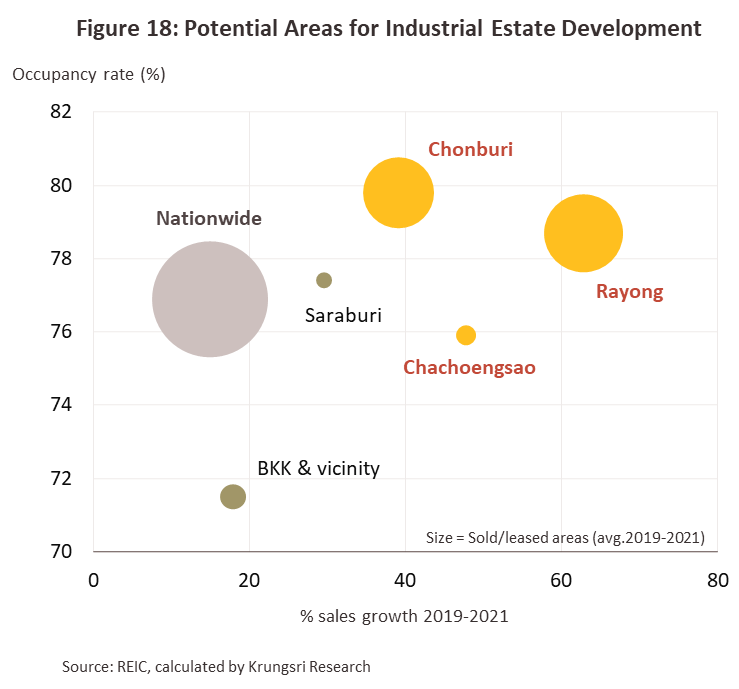

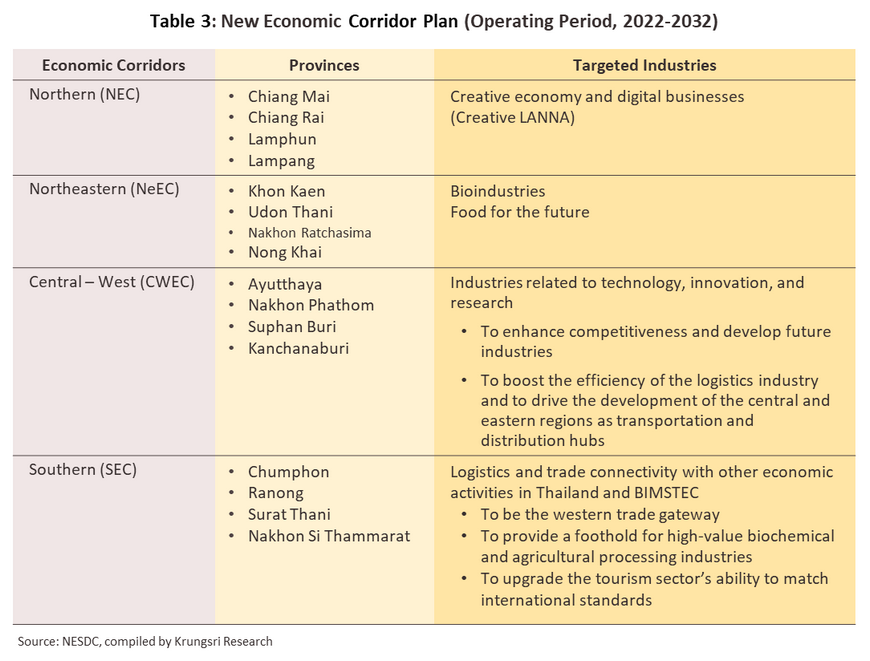

Industrial estates in the eastern region, and especially those in Chonburi and Rayong, continue to enjoy solid rates of growth (Figure 18), thanks to their location and continuing government support for their development. The latter includes the EEC development plan, which lays out a timetable for state investment in infrastructure megaprojects that will then be able to support the development of the government’s targeted industries. However, by comparison, industrial estates elsewhere in the country (e.g., SEZs that are spread across 10 provinces4/) have languished, and these have not yet attracted similar levels of interest from investors. This is because progress on the requisite infrastructure has been only slow and partial, but as of a cabinet resolution agreed on September 20, 2022, new ‘special economic corridors’ have been designated that cover 16 provinces in the northern, northeastern, central/eastern, and southern regions (Table 3). It is planned that the development of these will help to distribute economic development more equally and so ‘level up’ the regions, partly through the improvement of their transport and logistics links to the EEC and neighboring countries. The plan for the development of these economic corridors extends from 2022 to 2032, and the government intends to spend around THB 300 billion on their development (source: Krungthep Turakij, May 25, 2022). Nevertheless, it will be some time before these plans result in clear changes in current patterns of activity in industrial estates.

Unfortunately, it remains possible that Thailand’s neighbors may become more attractive investment targets than Thailand itself. In these countries, more favorable access to manufacturing inputs and more attractive labor markets means that investors in labor-intensive industries may put their money into industrial estates in these countries, rather than in Thailand. Beyond this, investment policies increasingly dictate that risk to supply chains be minimized by diversifying investments across a broad range of countries, rather than concentrating these in any one location. This may limit growth in the Thai industrial estates sector, and so to counter this possibility, the government should rapidly develop policies that better meet investor demands and respond more fluently to changing world trends. In particular, policy should aim to attract investors in the modern, tech-intensive S-curve industries.

[1] The principal differences between on the one hand industrial estates and on the other industrial parks and zones are that: 1) foreign companies may purchase land on industrial estates without the approval of the BOI, but may not do so in the case of industrial parks and zones; and 2) the IEAT acts on behalf of businesses on industrial estates as the certifier and provider of a variety of services, such as issuing permits to build and to operate factories, and thanks to its being a government agency, it is able to have applications for these (made to the Department of Industrial Works) processed more smoothly and more rapidly than can private sector operators. In the case of industrial parks and zones, conversely, the operator of the park/zone will itself be responsible for handling these services on behalf of the lessees or purchasers.

[2] The twelve targeted industries are: 1) next-generation automotive industries; 2) intelligent electronics; 3) high-value and medical tourism; 4) advanced agriculture and biotechnology; 5) food for the future; 6) automation and robotics; 7) aviation and logistics; 8) biofuels and biochemicals; 9) digital industries; 10) medical industries and comprehensive healthcare; 11) defense industries; and 12) education and human resource development.

[3] Holders of LTR visa: 1) are able to stay in Thailand for up to 10 years and to make use of the fast-track system when passing through immigration at international airports, only need to report to the immigration police once a year, rather than once every 90 days, and are exempted from the need to apply for re-entry permits; and 2) are subject to a reduced personal tax of 17%, provided that they are classified as highly skilled experts. LTR holders may also bring 4 dependents with them to Thailand on their visa.

[4] Phase 1 covers Tak (Mae Sod), Songkhla, Mukdahan, Sa Keao, and Trat. // Phase 2 covers Chiang Rai, Kanchanaburi, Nong Khai, Nakhon Phanom, and Narathiwat.

.webp.aspx)