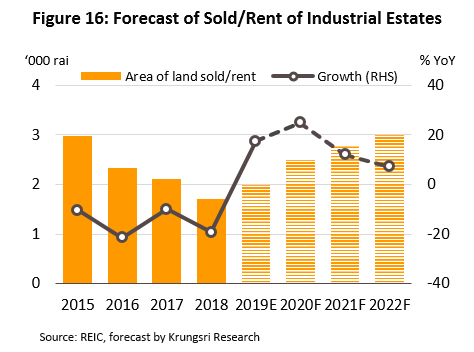

- Krungsri Research forecasts demand for space in industrial estates (to buy or rent) will grow by an average of 10-15% per year over 2020-2022. Business conditions have been sluggish since 2013 but there was a mild turnaround in 2019. And in the next few years, the industry will benefit from progress in developing the national infrastructure especially near the EEC which should be more visible soon. Meanwhile, the economy should strengthen in 2021 and 2022 as international trade tension dissipate.

- Prospects for industrial estate operators will depend on where the estate is located, how much of the area would benefit from government support, and the extent to which they can attract new capital from both domestic and international investors.

Overview

Industrial estates offer land for rent or purchase to industrial and commercial businesses, as well as supply businesses in the estates with access to amenities and utilities including electricity, water, flood mitigation systems, and centralized sewage services.

In Thailand, industrial estates are regulated by the Industrial Estate Authority of Thailand (IEAT). They manage (i) industrial estates that the IEAT owns and operates alone, and (ii) industrial estates that the IEAT owns and operates in partnership with private players.

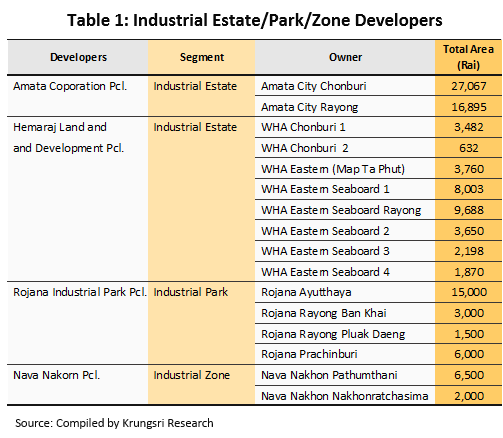

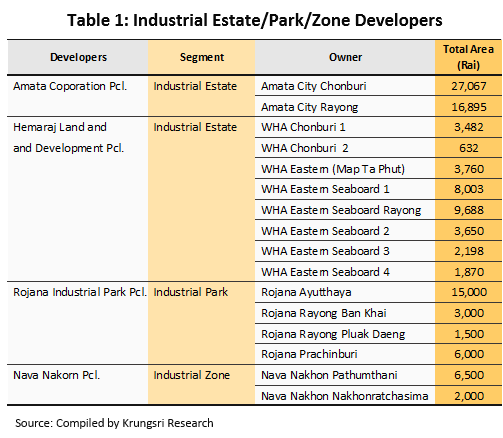

In addition, there are industrial parks and industrial zones – these share the characteristics of industrial estates but are privately-owned and operated. Examples include sites operated by Rojana Industrial Park and Navanakorn. These come under the Board of Investment which has delegated the regulatory task[1] to the Department of Industrial Works in each province.

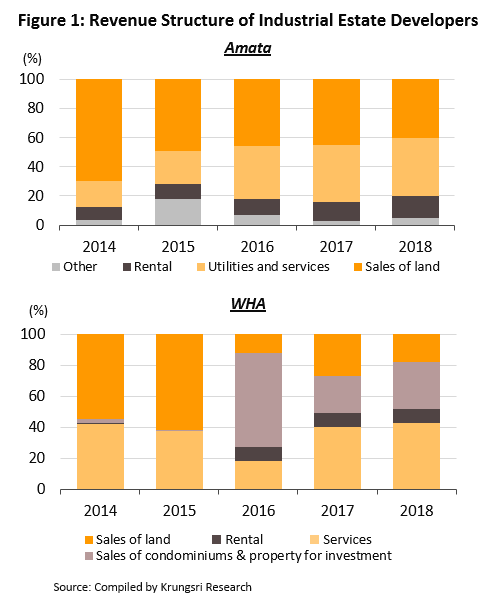

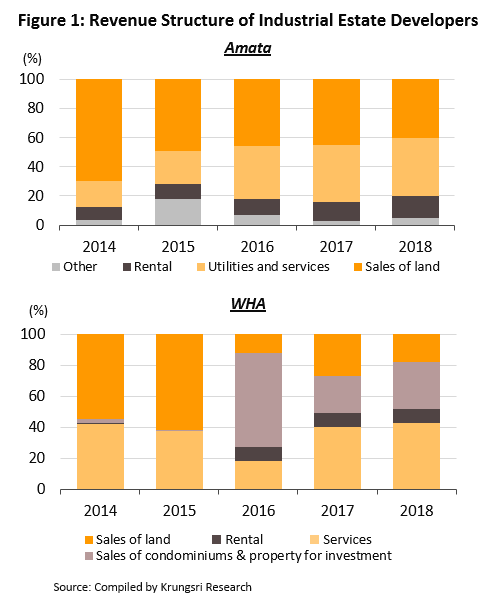

Industrial estate operators derive income from two principal sources: (i) leasing and selling land, and (ii) providing utilities and other services, and leasing out factories and warehouses, all of which generate recurring income and reduces the impact of volatile income from the sale of land. The revenue structure of two major industrial estate operators are shown in Figure 1.

Most businesses prefer to secure sites in industrial estates rather than build from scratch on empty land, because the former is equipped with the necessary infrastructure, utilities and transportation links. Locating operations in industrial estates could also benefit companies financially in the form of government incentives such as tax relief or investment support. The two major industrial estate operators in Thailand are Amata Corporation which operates Amata Nakorn, and WHA Group. Rojana Industrial Park and Navanakorn are the most important operators of industrial parks and industrial zones.

The critical factors that influence the growth of the industrial estate sector are: (i) infrastructure and services available within the estates; and (ii) appropriate regulations to support investment in domestic industrial estates, and the concessions and incentives offered to investors in the sector. Beyond this, the wider environment also affects the sector. They include: (i) the state of domestic and international economies and local political condition; (ii) multinational companies’ approach to investing and establishing production facilities in Thailand; and (iii) physical condition and geographical location of the country.

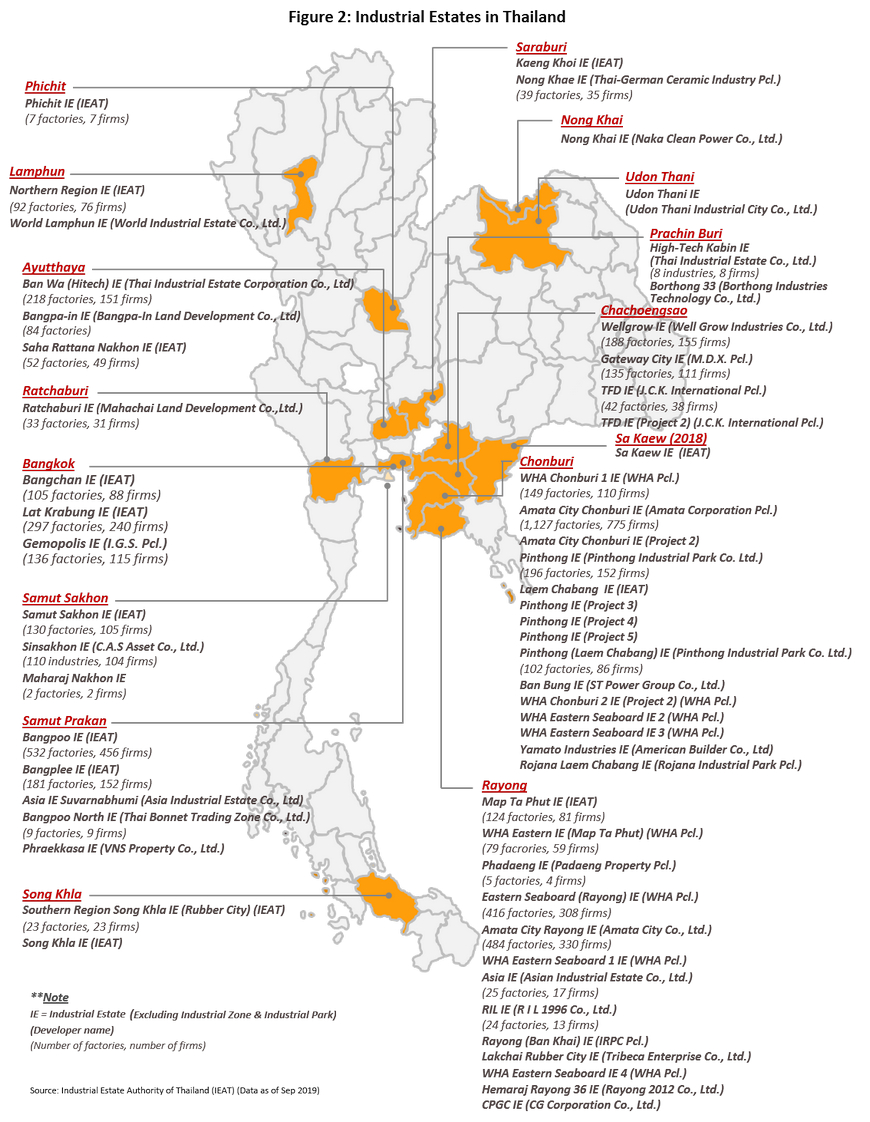

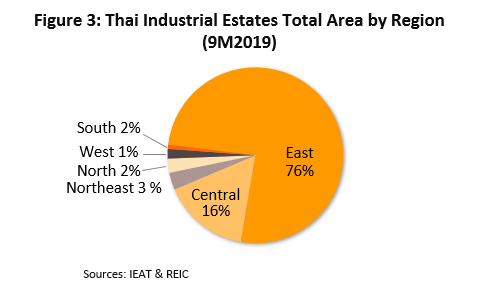

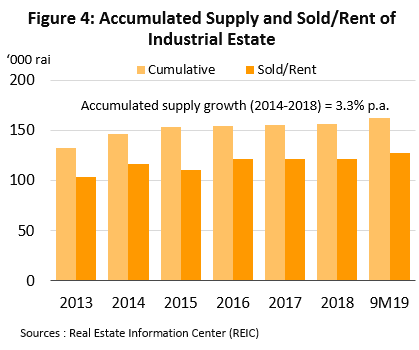

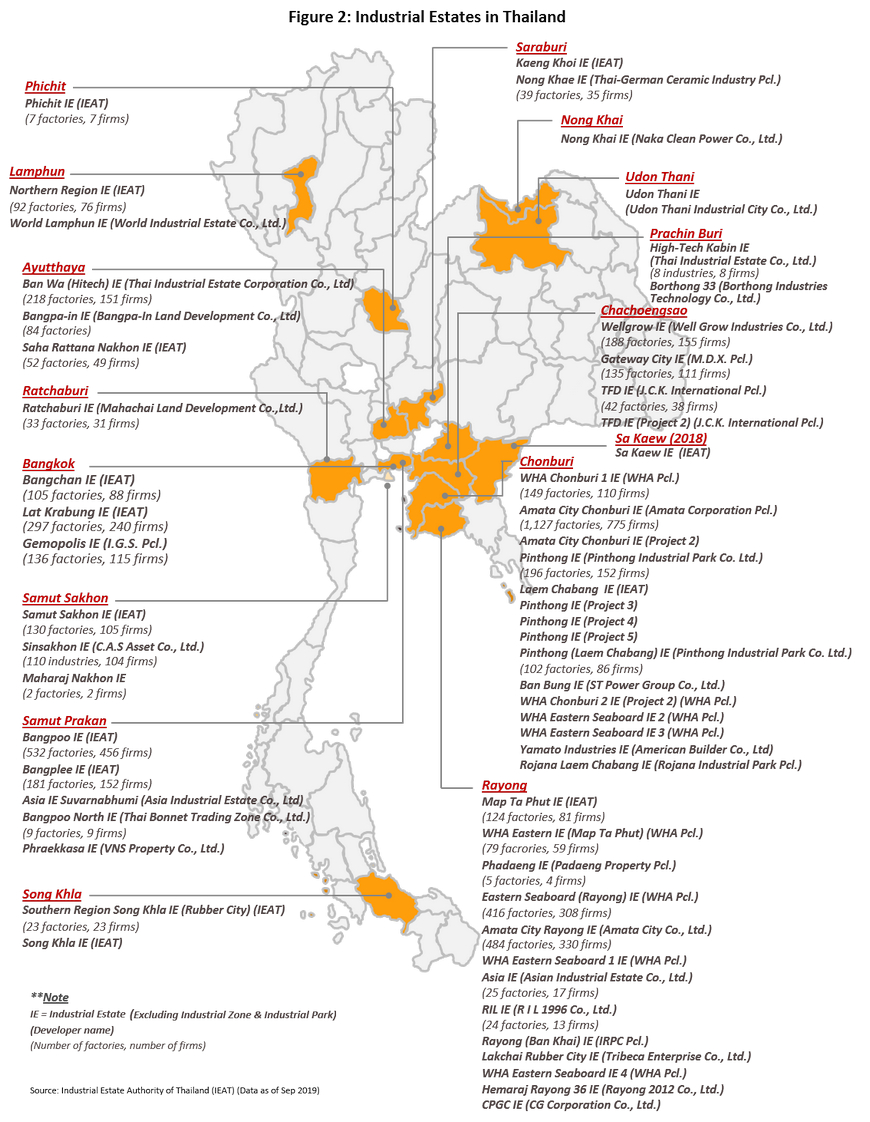

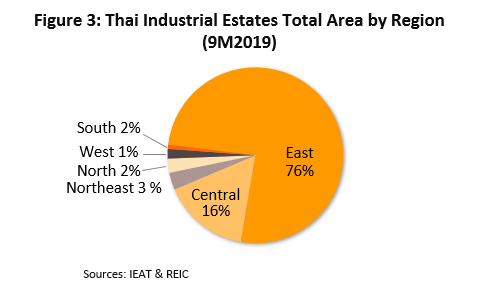

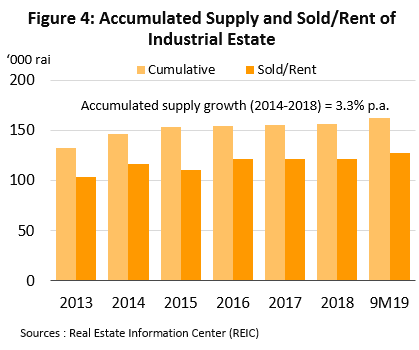

In September 2019, there were 59 industrial estates in Thailand, spread across 16 provinces (Figure 2). Of this, 14 were operated by the IEAT and the remaining 45 were joint-ventures with the private sector. The eastern region housed the vast majority (76%) of these (Figure 3), followed by the central area (including Bangkok Metropolitan Region) with 16%. Between 2013 and 2018, total industrial estate land – including new estates and expansion of existing estates – increased by only 3.3% (Figure 4). The slower supply growth was due to operators waiting for more clarity on new investment policies at that time.

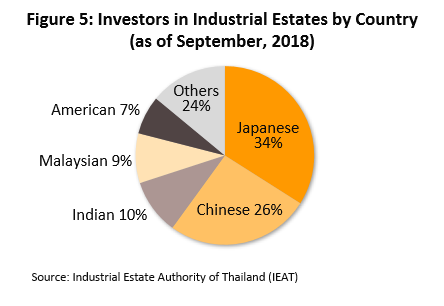

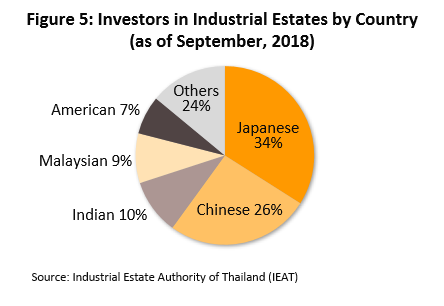

Looking at the investor profile, Japanese are the largest group of investors in Thai industrial estates based on investment value (Figure 5).

Across the country, the growth potential of the industrial estate sector varies by location. Details for individual regions are given below.

Eastern region: This area has the greatest potential for growth because it is home to a wide range of major industries, including oil refining and petrochemicals, chemicals, auto assembly and auto parts manufacturing, electronics, and food processing. Because of this, the region receives a substantial portion of government support for the sector. This has resulted in the eastern region having the highest concentration of industrial estates in the country, and attracting the most investors. The eastern region includes the Chonburi, Rayong, Chachoengsao, Prachinburi and other provinces. But for some time now, manufacturers operating in industrial estates in other provinces have been relocating their factories to this area because of connections to the Eastern Seaboard Development Program and an established communications network. The area has convenient road transport connections, is close to air links (Suvarnabhumi and U-Tapao airports) and commercial ports (Laem Chabang and Map Ta Phut), and Bangkok is nearby and easily accessible.

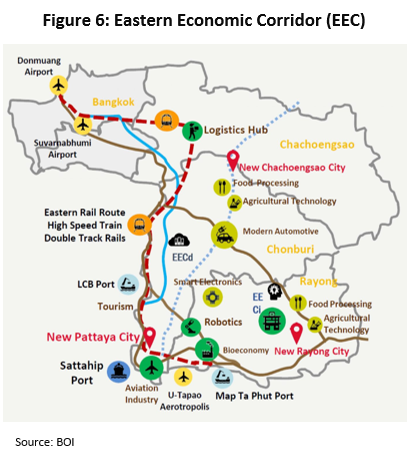

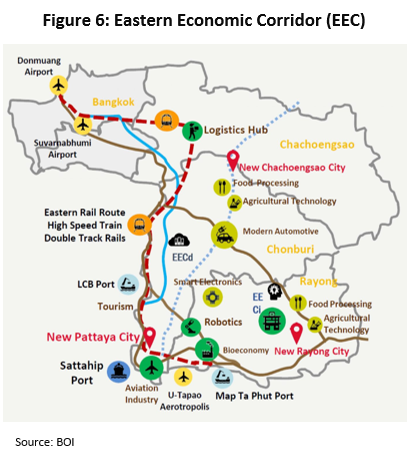

In addition, Chonburi, Rayong and Chachoengsao have been designated a part of the Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC) development (Figure 6) because they have good infrastructure. And because of this, public- and private-sector players can move in and start operations immediately. The EEC development will help attract interest from investors, and the government is hoping to attract investments in the 10 targeted industries[2], all of which are technologically and capital intensive.

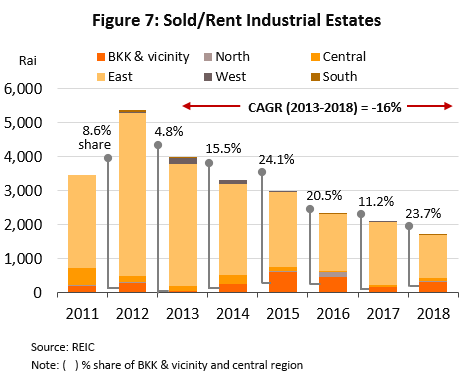

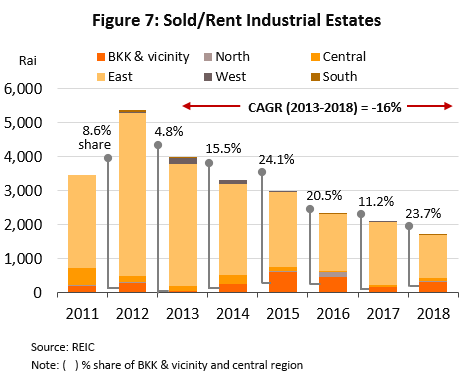

Bangkok and Central region: This region benefits from its location, as the center of manufacturing and national transport and communication networks. The central region includes Bangkok which is home to the most expensive industrial land in the area, and provinces with important industrial estates, including Samut Prakan, Ayutthaya, Saraburi, Ratchaburi and Samut Sakhon. Previously, auto parts, electrical appliances and electronics manufacturers had been concentrated in the area, along with industries that utilized local resources, such as food processing and construction materials. The region is still home to a large number of SME factories. However, industrial estates in the region had been badly affected by severe flooding in 2011 and demand (rent and sale) for industrial space in the region reached only 8.6% and 4.8% of the national total in 2012 and 2013, respectively. The situation has improved since, and between 2014 and 2018, they reached double-digit. This illustrates the continued ability of industrial estates in the Bangkok Metropolitan Region and wider central zone to attract investors (Figure 7).

Northeast and Northern regions: Industrial estates in these areas generally host food processing industries and some electronics manufacturers. However, communication links are inferior to those in other parts of the country, and this has curbed interest from investors. However, progress in developing communications in the northeast and links between northern Thailand and Myanmar and China should stimulate future investment. Most of the industrial estates are located in the northeastern provinces of Udon Thani and Nong Khai (these are currently being developed and expected to be operational in the near future) and in the northern provinces of Lamphun and Phichit.

Western region: This area, which includes Ratchaburi, will see more developments soon. The Industrial Estate Authority of Thailand plans to develop an industrial estate to support and connect to the proposed new industrial zone and deep-water port in Dawei, Myanmar.

Southern region: This region is being developed to improve connections between southern Thailand and Malaysia. The major industry here is rubber cultivation. Currently, it is host to only one industrial estate (in Songkhla). In 2016, the IEAT decided to halt development of a planned new industrial estate in Pattani province to house halal food processors, because of weak interest from both Thai and international investors due to lingering unrest in the region. The ongoing unrest in the deep south and insufficient electricity supply suggest little prospects to develop industrial estates in this area.

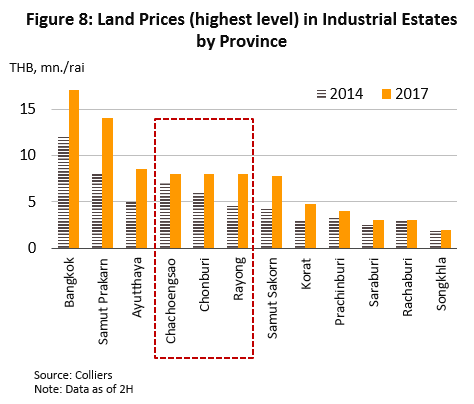

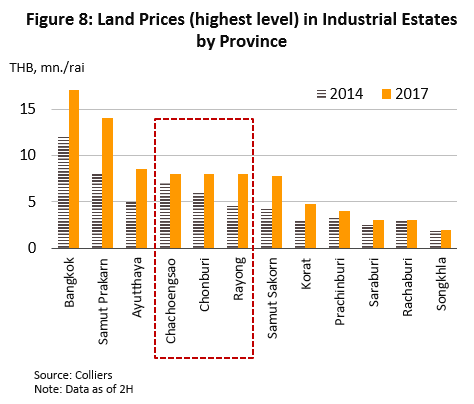

Cost of land (for both leasing and sale) varies among industrial estates and depends on several factors such as location, quality of utilities services, travel links, and access to raw material (Figure 8). Bangkok’s location in the center of land, water and air travel networks means that industrial estate land in the Bangkok Metropolitan Region is the most expensive in the country. This also pushed up land prices in adjacent areas such as Samut Prakan. Space in the EEC (Chonburi, Rayong and Chachoengsao) is the second most expensive in the country. In the second half of 2017, prices in these 3 provinces rose as high as THB8m/rai, about 30% higher than in the second half of 2014 (THB5.3m/rai) before the government stepped up efforts to promote the EEC (source: Colliers International). This suggests there is potential for future development in the area, which is an important factor to attract investors and government support.

Situation

In 2012, the total area of land sold or leased in industrial estates surged, especially in the eastern region. This was driven by severe flooding of 4Q11 which prompted foreign operators to move production facilities to industrial estates in the east of the country, and the decision by Japanese corporations to shift operations to Thailand following the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami.

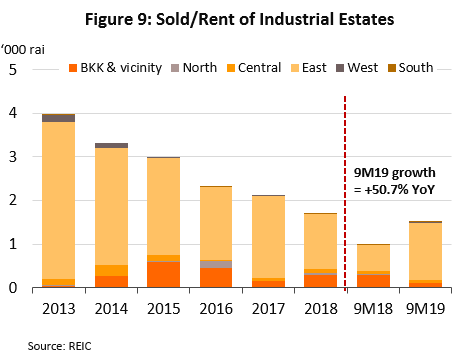

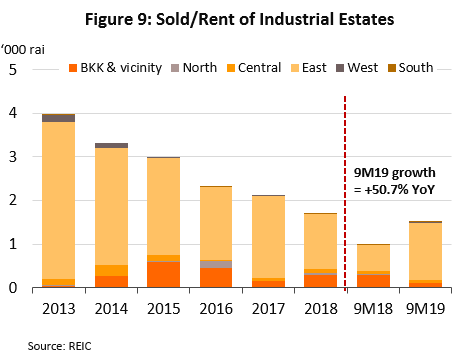

Between 2013 and 2015, the industrial estates sector was in a depressed state, and sale and rent of industrial space declined (Figure 9). The negative market conditions were caused by: (i) sluggish exports, which then weighed on the economy; (ii) drawn out domestic political conflicts between 2010 and 2014, which discouraged investors; and (iii) more stringent environmental[3] and health[4] impact assessment process, partly triggered by the serious air pollution at Map Ta Phut Industrial Estate in 2007 which also hurt investment especially in heavy industries and large-scale operations.

In 2016 and 2017, investment remained subdued. Land sale and leases in industrial estates shrank (Figure 9) as businesses waited for greater clarity on government policy, progress in investment in new infrastructure, and for the general economy to turn around. Hence, in these two years, private sector investment rose by just 0.6% and 2.9%, respectively, and land sale and leases in industrial estates nationwide shrank by 21.4% and 10.0%.

In 2018, investment started to pick up but land sale and leases continued to worsen.

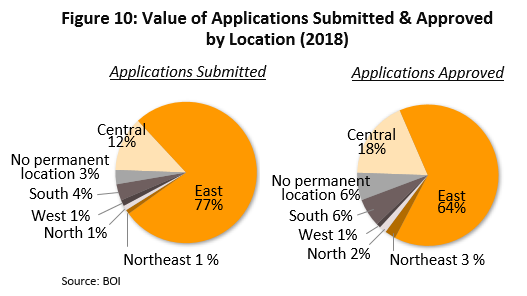

In 2018, there were 1,626 applications for BOI incentives. Although this represents only 3.1% growth, the total value of applications jumped by 43% to THB900bn.

The bulk of these (77%) were for projects in the eastern region, which total value increased at an even faster rate of 134% to THB690bn (Figure 10). This suggests the eastern region still appeals to investors and there is still growth potential. There is especially strong interest in the EEC, where the number of applications had dropped by 3.2% to 422 projects but investment value has surged by 137.4% to THB680b. Within this area, Chonburi received the most applications and highest investment value (Figure 11).

- Looking at BOI approvals, the situation was slightly different. The number of projects approved rose by 10.5% to a total of 1,469 but value slipped 12.9% to THB550b. Again, the greatest share of approvals was for projects in the eastern region, valued at THB350bn (+5.4%). And most of these (THB340bn) were in the EEC (+9.9%; Figure 11). Chachoengsao saw the strongest increase in the number of approvals (+52.4%), while by value, the largest rise was registered in Chonburi (+90.7%).

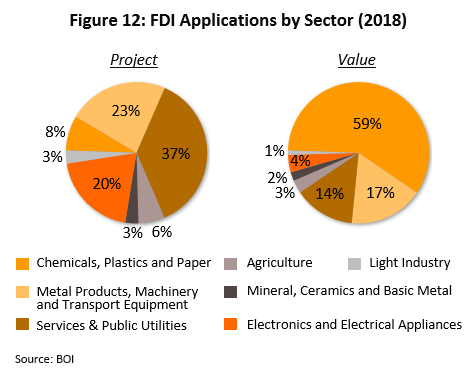

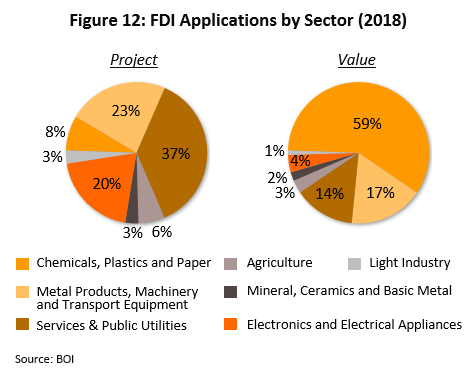

- In terms of foreign direct investment (FDI), in 2018, services and public utilities sectors attracted the greatest interest; these sectors accounted for 37% or a total of 387 of the 1,040 applications for BOI incentives. However, based on the combined value of THB344bn (59% of THB580bn worth of applications), chemicals, plastics and paper production were the most important (Figure 12).

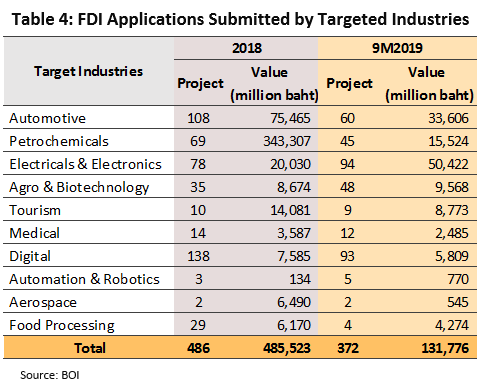

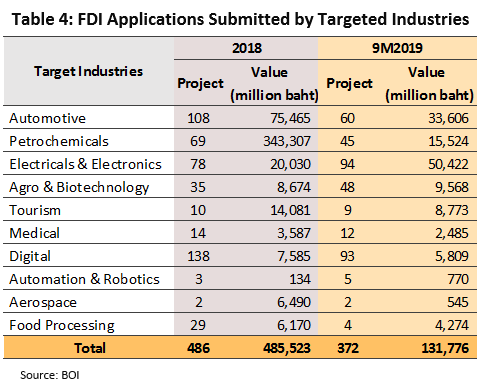

- In 2018, foreign investors submitted 486 applications for investment incentives for commercial activities in the government’s 10 targeted sectors (47% of 1,040 applications; Table 4). These had a combined value of THB490bn (84% of THB580bn). The majority of projects approved would be in industrial estates and industrial zones in Chonburi and Rayong provinces. The largest group of investors were the Japanese with 315 projects valued at THB94bn.

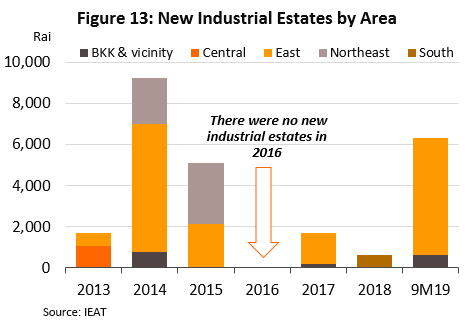

Small expansion in industrial estates footprint in 2018. There was only one new estate opened in the year. It had an area of 629 rai and was in Songkhla province, in the special economic zone in Sa Dao district (Figure 13). The industrial estate aimed to absorb some of the investment in the government’s targeted industries, especially auto assembly and logistics, although the estate also connects the region to trade and investment in neighboring Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore. The Songkhla estate raised the national tally of

industrial estates to 55 and increased total area to 155,903 rai (+0.2% from 2017 figure).

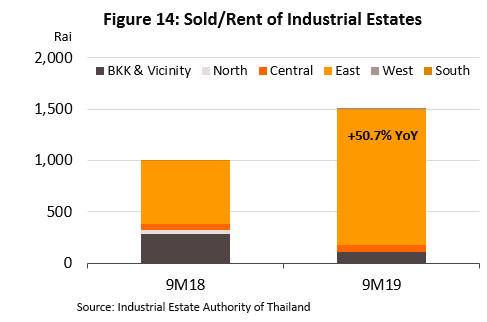

In 2018, the total area which changed hands (either rented or sold) in industrial estates shrank by 19.3% to 1,703 rai (Figure 9). Of this, 74% was in industrial estates in the eastern region. In 2018, 78% of the space in industrial estates nationwide (or 121,703 rai) was occupied (Figure 4).

This weaker land sale and leasing activity naturally hurt operators’ financial performance. WHA Corporation’s revenue fell by 6.3% and net profit contracted by 12.4%. For Amata Corporation, these fell by 1.6% and 27.8%, respectively, as available space in their estates were shrinking (especially in Amata City in Chonburi) and selling prices had risen (selling prices are higher than for other industrial estates). However, income from rent and the provision of utilities increased by 10.2% and 2.7%, respectively.

Situation for 9M19

- Land sale and rental rose 50.7% YoY in 9M19 to 1,510 rai (Figure 14). In the eastern region, it increased by a larger magnitude of 117.5% YoY. This lifted total space occupied to 127,873 rai, or 79% of all space in industrial estates.

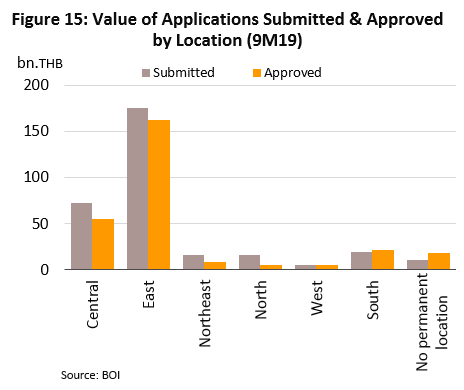

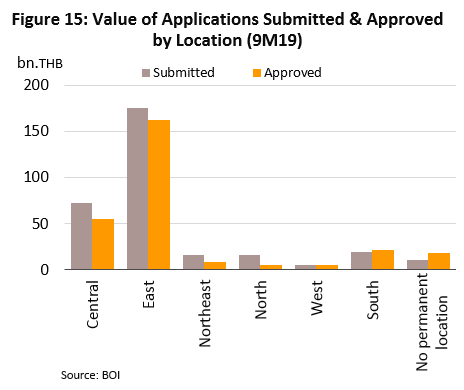

- Eastern region continued to attract investments in 2019. But overall, although the number of applications for BOI incentives increased by 11.2% YoY to 1,165, the value shrank by 11.2% YoY to THB310bn. This is because of an application for a single large-scale refining project worth THB160b a year earlier. Applications for BOI incentives in the eastern region reached THB180bn (53% of all applications), while approvals reached THB160bn (59% of all approvals) (Figure 15). By value, the largest group of applications were for the electrical appliances and electronics sector (THB52bn, or 17% of the value of all applications). But, petrochemical and chemical projects were the largest group in terms of approvals (THB74bn, or 27% of the total).

- There were FDI applications for BOI incentives in 689 different projects (+1.9% YoY). These had a value of THB200bn (+68.5% YoY). At the same time, the number of applications to invest in projects in industrial estates and industrial zones increased by 8.1% YoY, but surged 112.1% YoY by value.

- The largest single group of foreign investors receiving BOI support were the Chinese with 19% share (THB37bn) of the total THB190b worth of FDI. This is followed by Japan (THB29bn), Hong Kong (THB15bn), Singapore (THB7.3bn) and Indonesia (THB7.2bn).

- Supply of industrial estate space is expanding with the opening of 4 new estates. These are located in the central and eastern regions. These are developed to meet rising demand for space from investors in the government’s targeted industries, as laid out in the ‘new engines of growth’ policy. The 4 new sites are: (i) Prakesa Industrial Estate in Samut Prakan province (649 rai); (ii) CPGC Industrial Estate in Rayong province (3,068 rai); (3) Bo Tong 33 Industrial Estate in Prachinburi province (1,747 rai); and (iv) Rojana Laemchabang Industrial Estate in Chonburi province (841 rai). These four sites cover a combined area of 6,305 rai (Figure 6) and will increase total industrial estate space in Thailand to 162,536 rai. There will be 59 estates spread over 16 provinces, but 76% of the total area would be concentrated in the eastern region.

- For the last quarter of the year, overall investment should have improved given progress in the government’s infrastructure development plans. This will help to meet rising demand for industrial space in the first 9 months of this year. This, and given a low base a year earlier, should lift 2019 land sale and leases in industrial estates to 2,000 rai, representing an increase of 15-17% YoY.

Outlook

Krungsri Research forecasts that between 2020 and 2022, the industrial estate sector will see strong growth and land sale and leases will rise by an average of 10-15% p.a. to 2,500-3,000 rai (Figure 16). This outlook is supported by the following factors.

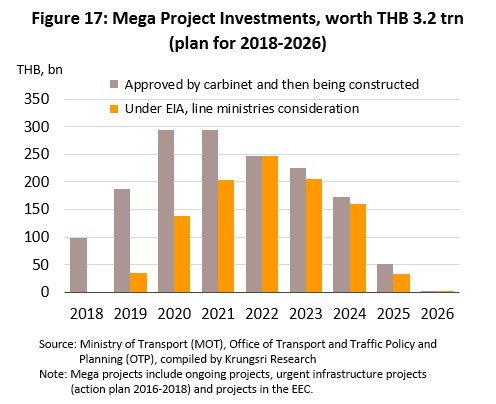

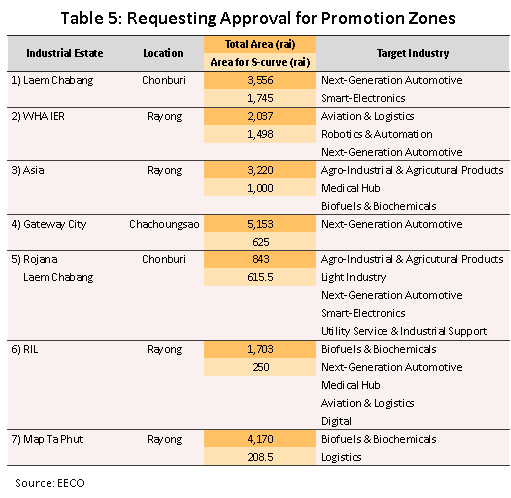

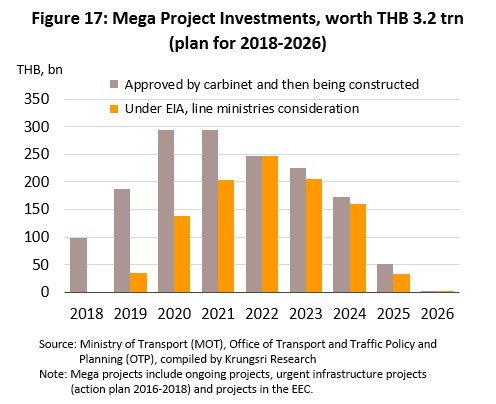

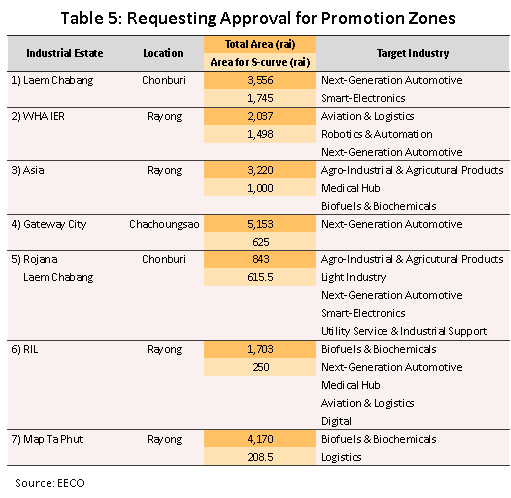

- Government measures to stimulate the economy and increase public spending: The most critical will be spending to develop the national infrastructure and an integrated communications network, which would reduce travel time and make transportation more convenient (Figure 17), and on developing the EEC. The EEC is a strategically important area that connects investment and trade in the region. Following the creation of the EEC, a large number of industrial estates are now moving to develop ‘special promotion zones’ to better meet rising demand for space in the EEC especially for the government’s targeted industries (Table 5). This will allow investors to claim additional benefits beyond those offered under the standard BOI schemes.

- Policies to stimulate investment, especially increasing the scope of tax incentives and reducing red tape: The government hopes that measures to extend tax benefits and reform the regulatory environment would make it easier to conduct business in Thailand, which would help to attract more FDI. Examples include the BOI Act to extend tax exemptions from 8 years to up to 13 years, and reduce tax rate by 50% for another 5 years. Under the Competitiveness Enhancement Act, Thailand will offer tax exemption for up to 15 years for companies that invest in the 10 targeted industries (provided that the investments are in industries that currently do not have a presence in the country). Other incentives are made available to investors in the EEC, including the right to lease state land for up to 50 years and to extend it by 49 years, the right to hold title deeds to land used to undertake certain activities, and to apply for 5-year work visas.

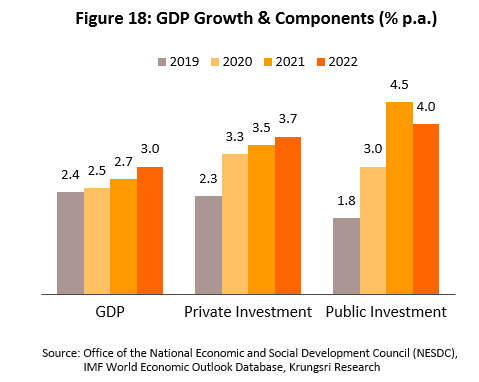

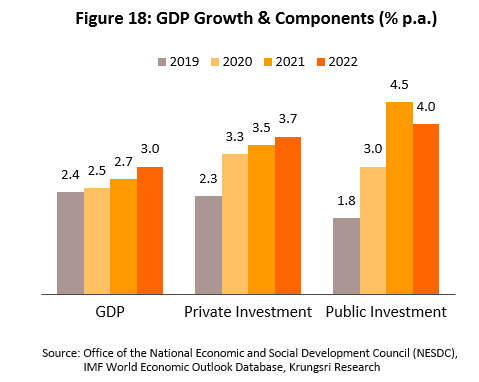

- Thailand’s economy is expected to grow in 2021 and 2022, and investments as well: The Thai economy is forecast to grow by 2.5% in 2020 (close to 2019 level), and by 2.7% and 3.0% in 2021 and 2022, respectively. Private sector investment is also expected to move in the same direction (Figure 18). In addition, the news trade barriers introduced in the past few years would be phased out gradually. The combination of these factors will boost income from land sale and leases, and the provision of utilities for industrial estate operators.

However, operators in some areas might see limited growth due to the following.

- Slow progress in implementing government policies: The development of special economic zones in 10 border provinces5/ is still being held up because of a lack of clarity over legislation. This has discouraged investors from investing in these areas. Today, the situation has not changed much we have yet to see plans to develop the critical infrastructure. Hence, these regions are unlikely to see more industrial estates in the near future.

- The Land & Building Tax Act: This should come into force on August 1, 2020, but it is still unclear how the provisions will be interpreted, especially for land to be developed into industrial estates. This could increase costs for manufacturers and hurt profitability. Because of this, manufacturers have been slow to commit to investing in industrial estate land or to expand factories.

- Cheaper factors of production in other countries: Neighboring countries may have an advantage over Thailand. This comprises both inputs or labor. This could encourage some manufacturers, especially those in labor-intensive industries, to invest in neighboring countries, rather than in Thailand.

Krungsri Research view:

Demand for industrial estate space (buy or rent) will grow in the coming period but operators’ income will vary by area. The outlook for the major regions are given below.

- Industrial estates in the eastern region: Operators in the eastern region will benefit from a stronger business environment and rising demand for space (rent or lease). Operators here will benefit from government spending on infrastructure to support the development of the EEC (in the three provinces of Chonburi, Rayong and Chachoengsao), the bulk of which would be spending to upgrade infrastructure. This will attract more investment and improve transport links in the region including: (i) Chachoengsao-Khlong Sip Gao-Kaeng Khoi and Kaeng Khoi-Map Ta Phut double-track railway; (ii) Pattaya-Map Ta Phut motorway; (iii) commercial development of U-Tapao Airport; (iv) Phase 3 of Laem Chabang Port; and (v) the Bangkok-Rayong high-speed rail-link. However, although rising private sector investment over the next 3 years will fuel the growth of industrial estate land in the region, slow progress in government construction projects, weak enforcement of the new Land & Building Tax Act, and rising land prices, will all have an impact on the sector.

- Industrial estates in the Central region: Earnings should grow solidly for industrial estate operators in this region. The supply of industrial estate space will expand and the region’s communications network will continue to be an advantage. But at the same time, the region will face competition from the eastern region which seems to offer more attractive incentives to investors. This will divert interest from investors who might otherwise have invested in the central region.

- Industrial estates in Northeastern and Northern regions: In these regions, operators are waiting for progress in the border special economic zones. Government spending on infrastructure is likely to pick up from 2020. This should help to attract more private sector investment, but overall, the outlook for these regions is that growth would be slower than in the Central and Eastern regions.

- Industrial estates in Southern and Western regions: The situation here is dependent on government policies. In the west, there is the question of what will happen with the Tawai deepwater port, but his is now less important because the Myanmar government has switched its attention to develop the Thilawa industrial area in the Thilawa special economic zone. Meanwhile, in southern Thailand, there is infrastructure development but operators are concerned about the fragile political situation there. Hence, turnover is likely to remain weak.

[1] The principal differences between on the one hand, industrial estates and on the other, industrial parks and zones, are that: (i) foreign companies may purchase land in industrial estates without the approval of the BOI, but may not do so in the case of industrial parks and zones; and (ii) the IEAT acts on behalf of businesses on industrial estates as the certifier and provider of a variety of services, such as issuing permits to build and to operate factories, and thanks to its being a government agency, it is able to have applications to the Department of Industrial Works for these processed more smoothly and more rapidly than can private sector operators. In the case of industrial parks and zones, conversely, the operator of the park/zone will itself be responsible for handling these services on behalf of the lessees or purchasers.

[2] The ten targeted industries are: (i) next-generation automotive industries; (ii) smart electronics; (iii) affluent and wellness tourism; (iv) agriculture and biotechnology; (v) food for the future; (vi) automation and robotics; (vii) aviation and logistics; (viii) biofuels and biochemicals; (ix) digital industries; and (x) medical hub-related.

[3] EIA: Environmental impact assessments evaluate the environmental effects, positive and negative, of different types of projects carried out by the private and public sectors in order to prepare measures in advance to control, protect against and remedy undesired consequences.

[4] HIA: Health impact assessments analyze the effects on the health of the population of constructing and operating certain projects.

[5] Phase 1: Tak (Mae Sot), Songkhla, Mukdahan, Sa Kaew, and Trat provincesPhase 2: Chiang Rai, Kanchanaburi, Nong Khai, Nakhon Phanom and Narathiwat provinces

.webp.aspx)