EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Mass transit services are a relatively stable and solid structure than other services because they are typically in the form of public-private partnerships providing a necessary public utility. Moving forward, income should grow as demand for public transport partly displaces use of private vehicles, a process that will be accelerated by the expansion of integrated rail transport networks. Alongside this, demand will be further lifted by the fading of the COVID-19 pandemic, which is bringing with it recovery in domestic and international tourist markets and in social and economic activity more broadly. As such, service operators can expect to see income rise from fares, the management of commercial spaces in and around stations, and fees charged for the maintenance and repair of metro systems.

Against this broadly positive outlook, rising energy costs are weighing on business overheads, while high inflation is eroding consumer spending power, and this will be a particular problem over 2022 and 2023. And together, these factors will tend to limit how far or fast players’ income rises.

Krungsri Research view

Overall, mass transit service providers enjoy a considerable degree of business stability because their investments are in joint ventures with the government in providing a necessary public utility that is in high demand. In addition, mass transit concessions are typically awarded for lengthy periods of time (generally in excess of 25 years), and the conditions laid out in concession contracts for the division of returns allow private-sector partners to maintain profitability over the long-term.

-

Through 2022, operators will generally see their income slowly strengthen on: (i) a gradual recovery in consumer spending power that will be driven by a rebound in the economy; (ii) high vaccination rates (around 80%) that will encourage the public to return to normal levels of economic and social activity, including working and studying on site; (iii) the full reopening of the country and the subsequent rapid rise in tourist arrivals; and (iv) ongoing government stimulus spending that includes measures to promote domestic tourism.

- Over the three years from 2023 to 2025, incomes should continue to rise on greater passenger numbers, the latter being lifted by: (i) the construction of new residential accommodation along metro lines and around the areas served by these; (ii) ongoing and severe problems with traffic congestion that will underpin greater demand for a reliable and rapid way of traveling into the city center; and (iii) the full opening of new lines, which will extend the total coverage of the metro system. Overall incomes should thus increase, not only for passenger fares but also for the provision of operation management system and maintenance services, and for the management of commercial spaces. Players already operating mass transit concessions that win the right to operate extensions or wholly new routes will therefore benefit from the increased number of lines, interchange stations, and length of track that they will manage and the opportunities to generate income that this will provide.

OVERVIEW

Mass rapid transit systems are a form of public rail transport[1] that has attracted ongoing spending by the Thai government as it looks to alleviate some of the problems with road traffic congestion that plague the Bangkok Metropolitan Region (BMR)[2]. Bangkok’s mass rapid transit system is thus a public utility or public service provided by the government for commuters and travelers, who may choose between using the metro system or the other forms of public transport that are available in the BMR, such as buses, shared taxis, minivans, the Bus Rapid Transit system, the suburban-urban rail system, and boat services running on rivers and canals.

Urban mass rapid transit systems use rolling stock that travels at mid to high speed (80-160 kph) on tracks that are separated from other transport systems (i.e., there is no interaction between mass rapid transit systems and other transport modalities). Tracks may run underground, above ground, or on elevated platforms, depending on the environment in which the system is constructed. Urban rail, light trams, monorail, and light and heavy rail trains may all be used in such a system.

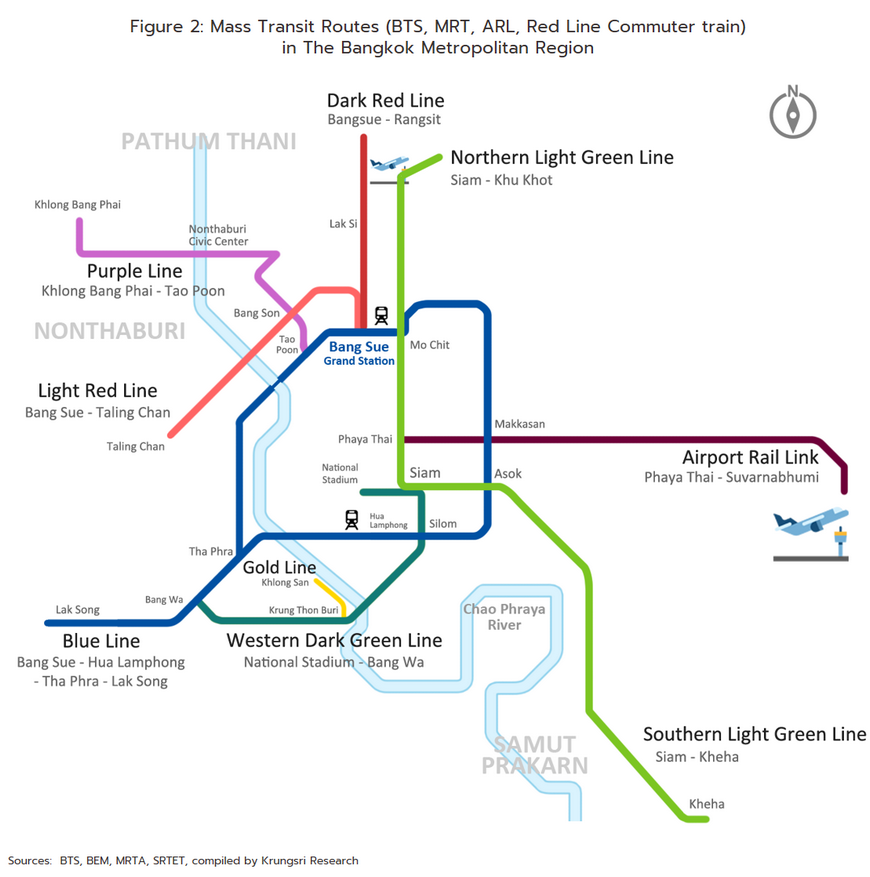

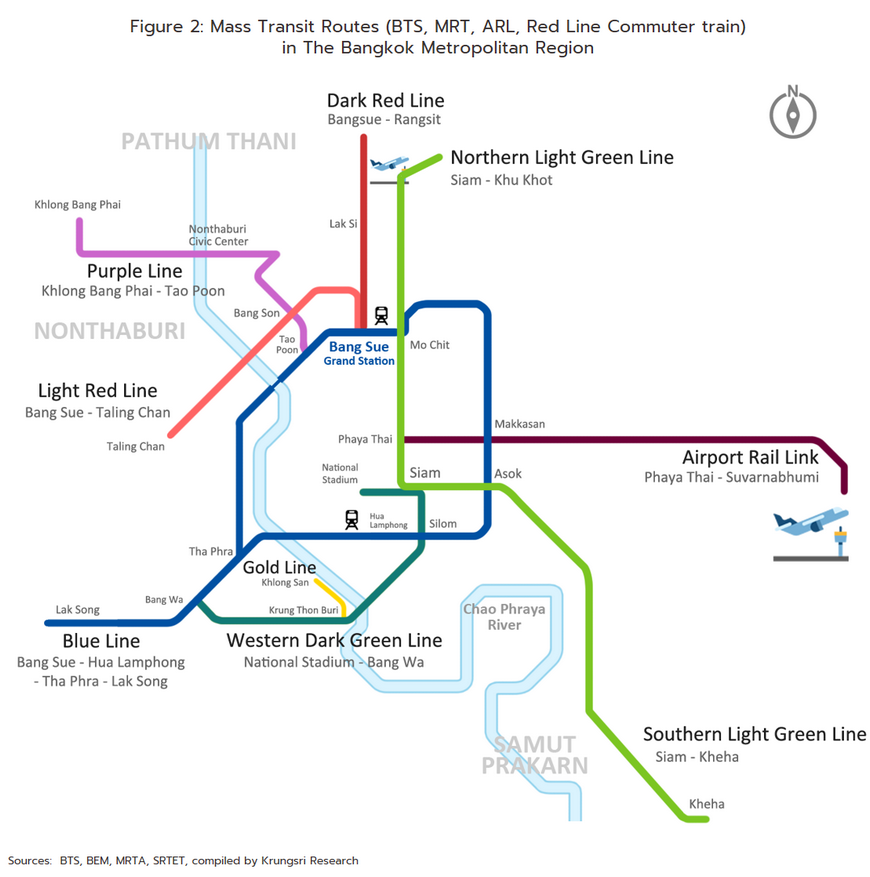

The first mass rapid transit line to begin operations in Bangkok was the Chalerm Prakiet Skytrain line, which is based on a heavy rail line that connects inner Bangkok with a wider area of central Bangkok[3]. This opened for operations in 1999 and since then new lines have continued to be added or extended such that at present, the city’s rapid mass transit system comprises 8 lines, 140 stations, and 211.1 kilometers of track (Figure 2). The entire system is composed of the following:

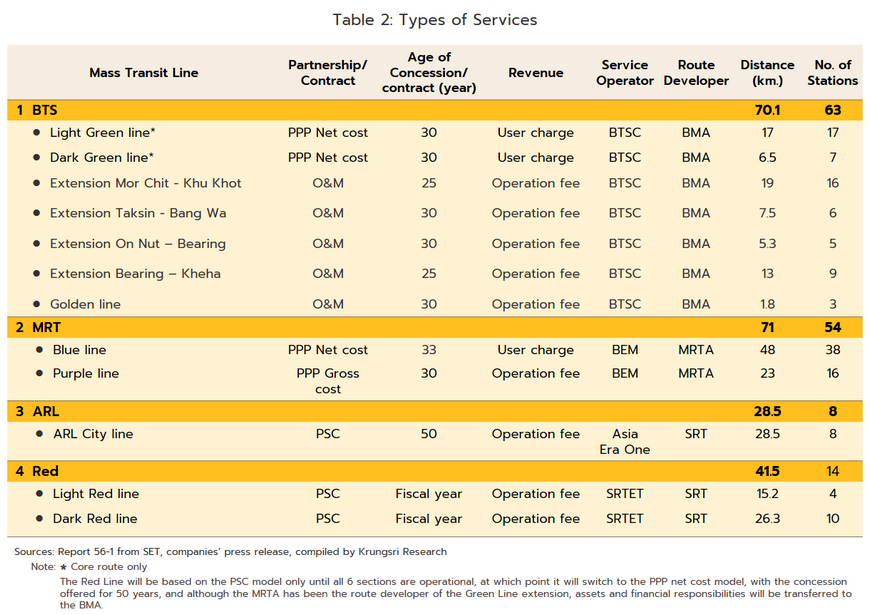

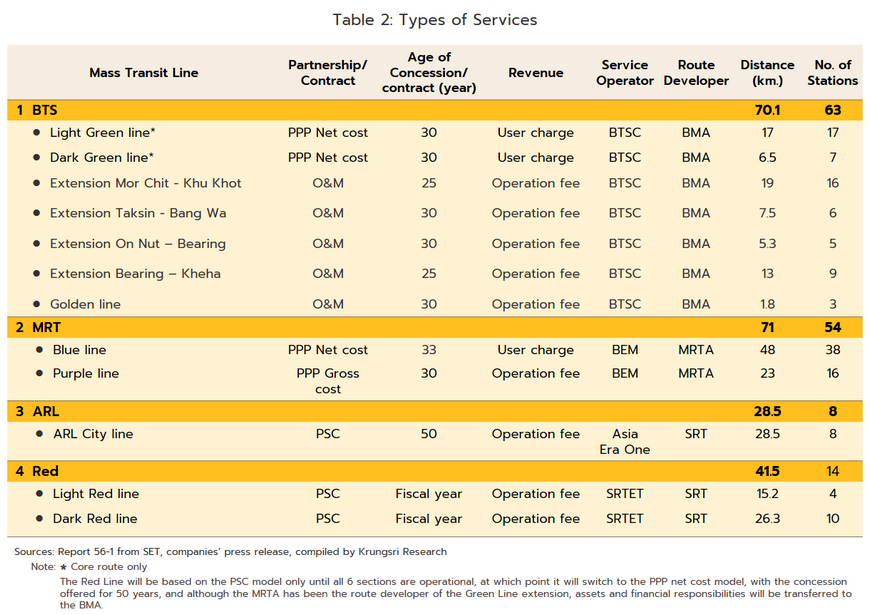

1) Bangkok Mass Transit System (BTS) Green Line: This is a heavy rail line running north-east and connecting the three provinces of Pathum Thani, Bangkok, and Samut Prakan. The line covers 68.25 kilometers and 60 stations (including the interchange station Siam), and is made up of 2 sub-lines.

-

The BTS Chaloem Phra Kiat or Sukhumvit line (the Light Green Line): Currently runs from Khu Khot in Pathum Thani to Samrong/Kheha over 54.25 kilometers and through 47 stations. The first section of the line (Mor Chit-On Nut) opened in 1999 and is operated by Bangkok Mass Transit System Plc (BTSC). The company was awarded a 30-year concession (1999-2029) by the Bangkok Metropolitan Authority (BMA), and under this the BTSC are required to install equipment, maintain and repair rolling stock, and manage operations across the line. The Mo Chit-Khu Khot and On Nut-Bearing-Samut Prakan extensions to the line were progressively opened over 2011 to 2020, with the BTSC again in charge of operations, though this time it was hired in by Krungthep Thanakom (KT), a commercial operation owned by the BMA. This contract between BTSC and KT will run until 2042.

-

Silom (Dark Green Line): This runs from National stadium to Bang Wa, covers 14 kilometers, and passes through 13 stations. Operations began in 2004, with extensions to the original line then opening to the public between 2009 and 2013. BTSC won the right to operate this line and so is responsible for installation and maintenance of equipment and of daily operations. As with the Silom Line, it was the BMA’s commercial arm KT that hired in BTSC to do this. The Silom Line connects to the Sukhumvit Line at the Siam station, which with a 2019 daily average of 66,000 users is the network’s busiest.

2) BTS Gold Line: This is a light railway built using a straddle-type monorail that runs for 2.7 kilometers from Krung Thonburi to Khlong San/Saphan Phut. This is an automatic system that operates without drivers but which passes through central areas that have high levels of traffic congestion. The line operates as a ‘feeder’ integrating rail transport with travelers moving by bus along nearby roads and by water along the Chao Phraya River. Phase one of Gold Line operations began in 2020 and connected Krung Thonburi to Khlong San through 3 stations and over 1.8 kilometers of track, and again, KT has given BTSC a 30-year concession to manage operations and maintenance. Phase two of the line will add 0.9 kilometers of track and one more station (Prajadhipok), but this is not yet operational.

3) Metropolitan Rapid Transit (MRT): This is a heavy rail mass transit system that circles the city, connecting central parts of Bangkok, Thonburi, and Nonthaburi. In total, the MRT network covers 71 kilometers of track and includes 54 stations. The MRT network is split into 2 core lines.

-

MRT Chalerm Ratchamongkhon Line (the Blue Line): This stretches for 48 kilometers from Tha Phra to Hua Lamphong and passes through 38 stations. The Hua Lamphong-Bang Sue section was opened in 2004, though as time has gone on, the number of interchanges with other lines has increased. Thus, in 2017, this was linked with the Chalong Ratchadham Line (the Purple Line) at Tao Poon, with the Hua Lamphong-Bang Khae Line in 2019, and with the Bang Sue–Tha Phra Line in 2020. At present, the operating concession is held by Bangkok Expressway and Metro (BEM) as a 33-year ‘through operation’ from the Mass Rapid Transit Authority of Thailand (MRTA), and so the Blue and Purple lines run as part of a single network.

-

MRT Chalong Ratchadham (Purple Line): This covers 23 kilometers and 16 stations between Bang Yai and Bang Sue. Operations began in 2016 and then in 2017, services were extended with the construction of an interchange with the Blue Line. The MRTA has awarded the BEM a concession to operate and to maintain the line for the 30 years from 2016 to 2046.

4) The Airport Rail Link (ARL), also called the AERA1 City Line: This heavy rail line connects Suvarnabhumi Airport with the City Air Terminal at Makkasan Station. Asia Era One has been given a 50-year concession (2019-2069) by the State Railway of Thailand and the Eastern Economic Corridor Office of Thailand to operate rail services and to develop commercial space within the station. The company is also required to build and manage a high-speed rail-link connecting Bangkok’s three airports (Don Muang, Suvarnabhumi, and U-Tapao) that will connect with the existing Airport Rail Link. This has two sections.

-

Suvarnabhumi Airport City Line (SA): The section from Phaya Thai to Suvarnabhumi comprises 8 stations and 28.5 kilometers of track. This was opened to the public in 2010.

-

Suvarnabhumi Express Line (MAS): This covers the 25.7 kilometers from Makkasan to Suvarnabhumi but because this is an express service, there are no intermediate stations. The line offers a check-in counter and a system for transporting passengers’ baggage to Suvarnabhumi. The line was open for operations between 2010 and 2014 but at present it is inactive.

5) SRT Mass Transit Commuter Train (Red Line): This is a heavy rail line that provides a feeder service for people traveling in suburban areas along the Taling Chan-Bang Sue (Krung Thep Aphiwat Central Station[4])-Rangsit axis. This is currently operated by SRTET (a state enterprise operated by the State Railway of Thailand) on a rolling annual basis, though the SRT plans to offer a 50-year operating concession to the private sector once all 4 sections and 54.24 kilometers of the line are operational. Initially, 13 stations (including the Bang Sue Central Station[4]) and 41.5 kilometers of track were opened to the public at the end of 2021. This line is split into 2 sections.

-

Nakhon Withi (Light Red Line): This covers 15.2 kilometers between Bang Sue and Taling Chan. At present, 3 of 5 stations are operational but this is just the initial stage of what will be a 54-kilometer line running east-west between Hua Mak and Salaya in Nakhon Pathom.

-

Thani Ratthaya (Dark Red Line): This line passes through 10 stations and covers 26.3 kilometers along the stretch from Bang Sue to Rangsit. This is, though, only the first section of a planned 80.5-kilometer north-south line that will connect Mahachai in Samut Sakhon with the Thammasat University Rangsit campus.

Private-sector players wishing to offer services as mass transit operators need to obtain a concession from the government, and so corporations will compete against one another when bidding at auctions for these, though concessions are offered for each line independently. In these cases, the ‘route developer’, i.e., the body responsible for overseeing the project, will be the government or one of three state bodies: (i) the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (BMA), although this managed through the BMA’s commercial undertaking, Krungthep Thanakom; (ii) the Mass Rapid Transit Authority of Thailand (MRTA); and (iii) the State Railway of Thailand (SRT). The winner of the concession is referred to as the ‘service operator’, and at present there are three of these: (i) Bangkok Mass Transit System Public Company (BTSC); (ii) Bangkok Expressway and Metro Public Company Limited (BEM); and (iii) SRT Electric Train Company (SRTET).

In addition to the state of the economy and the cost of living (both of which may affect ridership), concession holders’ income may also be affected by the particular terms and conditions of individual contracts and any additional agreements reached between service operators and the government or other state bodies.

Several different business models have been put into practice within the mass transit system, and these are described below.

1) Investment structure: Because investing in mass transit systems typically involves considerable sums of money for which returns are generally made over only extended timescales, these projects are normally undertaken as joint investments by the public and the private sector. There are two main ways of structuring these:

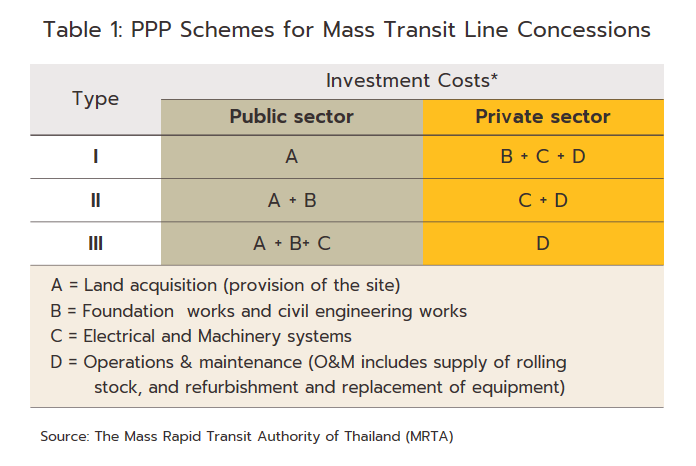

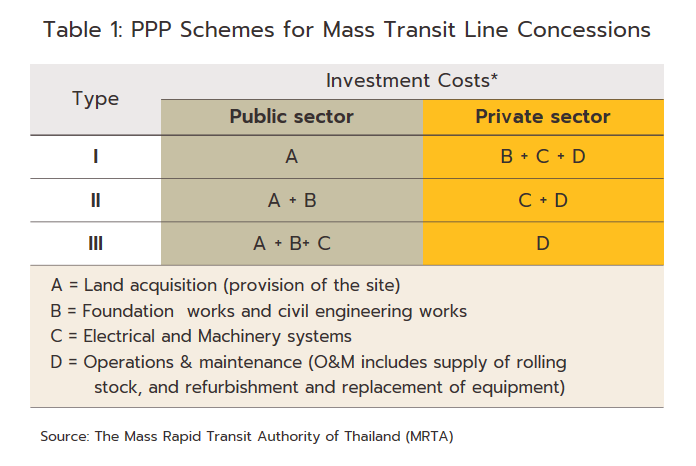

1.1 Public-private partnerships (PPPs)[5]: These all involve some degree of joint investment by the public and private sectors, but how this is split between the two and decisions over how the project will be managed will depend upon individual circumstances[6]. PPPs can however be divided into three main groups (Table 1).

-

Group 1 is a group that the public-sector partner is responsible only for acquiring the land used in the project, and all other costs are borne by the commercial partner, including structural engineering, construction work and civil engineering, installing electrical equipment and machinery, and operating rolling stock (sourcing trains, operating these, and maintaining and repairing electrical systems and equipment);

-

Group 2 is a group that the public-sector partner is responsible for acquiring the land used in the project and for overseeing structural engineering, construction work, and civil engineering, while the private-sector partner will be responsible for installing electrical systems and equipment and for operating rolling stock; and

-

Group 3 is a group that the public-sector partner is responsible for all aspects of the project with the exception of the operation of the trains, which is left to the commercial partner.

1.2 Under the public sector comparator (PSC) system: The public sector is solely responsible for all spending at all stages of the project, and the private-sector partner’s involvement is restricted to being hired in to run the system. Thus, in these projects, the route developer will pay the commercial partner a rate laid out in the concession contract, though this will expose the private-sector player to the risk of seeing their contract cancelled if income fails to meet the targets set for the project or if the company generates losses.

2) For PPP concessions, there are three main ways of splitting the returns between the service provider and the route operator[7], though this covers only income from fares and the management of commercial space within or around stations and does not cover income from the maintenance and repair of equipment.

2.1 Net cost concession: Under these schemes, the private-sector partner will retain the income generated from operating the system and collecting fares, though they will have to return a fixed fee to their public-sector partner as per the concession agreement. This then means that the commercial partner has the opportunity to generate additional income if receipts from fares or from the renting out of commercial property in stations is greater than anticipated. However, the reverse of this is that they may have to accept losses if ridership fails to meet their targets.

2.2 Gross cost concession: These are the reverse of net cost concessions, with the government collecting fares and then making regular fixed payments to the private-sector partner, again, as determined in their service contract. Under this system, income for rapid mass transit system operators will not fluctuate with overall operations and so this form of concession helps to reduce risk for private sector partners in the first ten years of operations, a period when income may be uncertain and investors may face the possibility of making losses.

2.3 Modified gross cost concession: Under this system, as with gross cost concessions, the government will collect fares from passengers but payments to the private sector partner will be in two parts: (i) fixed payments as compensation for the operation of services, made on a timetable and to a level set in advance in the contract (as with the gross cost concession model); and (ii) a bonus, paid when the number of journeys/travelers or income from commercial property is greater than expected. However, as yet, no mass transit projects have been structured on this basis.

The development of Bangkok’s mass transit system is at present directed by the Mass Rapid Transit Master Plan in Bangkok Metropolitan Region, which covers the period 2010 to 2029. This aims to tackle problems with Bangkok’s congestion and to cut associated costs through the development of the metro system, and in particular by pushing forward with the creation of a single, unified mass transit rail system[8] that allows travelers to easily change between lines. Initially, the authorities emphasized the rapid construction of the system’s 10 main lines, and where lines touch or cross, interchange stations have been built that allow travelers to change lines (Figure 3). Over 2022-2028, the government’s investment plans dictate a greater focus on spending on extensions to existing lines and on the Don Muang-Suvarnabhumi-U-Tapao high-speed rail-link, as laid out in the government’s schedule for spending on megaprojects. Work is also ongoing on the buildout of 14 new high-speed rail lines with a total length of 554 kilometers.

Of the 8 lines that are currently open to the public, the largest share are public-private partnerships structured on the net cost model. These include the BTS Gold and Green lines (the latter in fact encompasses 2 lines) and the MRT Blue Line. The MRT Purple Line is a PPP gross cost concession, while the ARL and the SRT Red Line (also 2 lines) split public- and private-sector responsibilities and returns according to the public sector comparator model, with the state hiring in the service operator to oversee management of the system as agreed in the relevant contract (Table 2).

Future changes in income and improvements in the general business outlook will largely be determined by increases in ridership, an expansion in the service area and number of stations, and the development of additional commercial space. As for fares and charges for repairs and operations, these are to a large extent determined by the government, and how and when increases in these may be made will be specified in the original concession agreement, although occasionally, fares may even be cut (for example during economic crises). There is therefore substantial variation in the prospects for individual service providers, with the opportunities and threats faced by concession holders or line operators heavily influenced by the length and the structure of their particular investment.

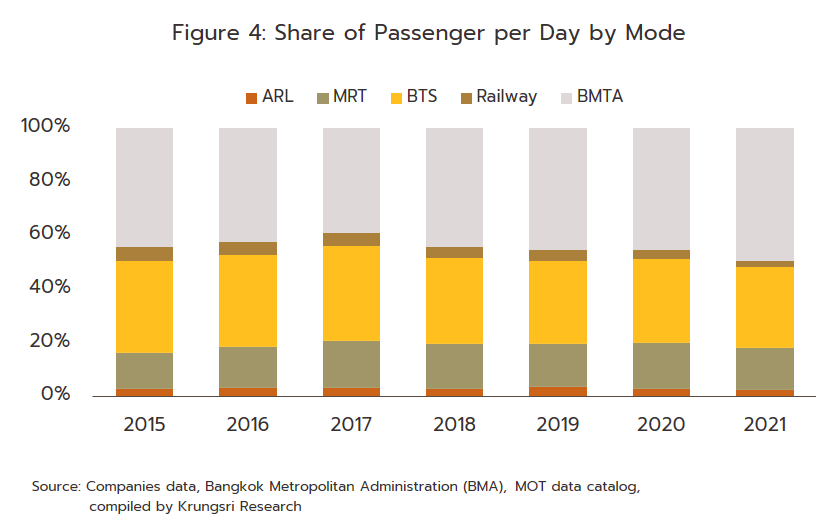

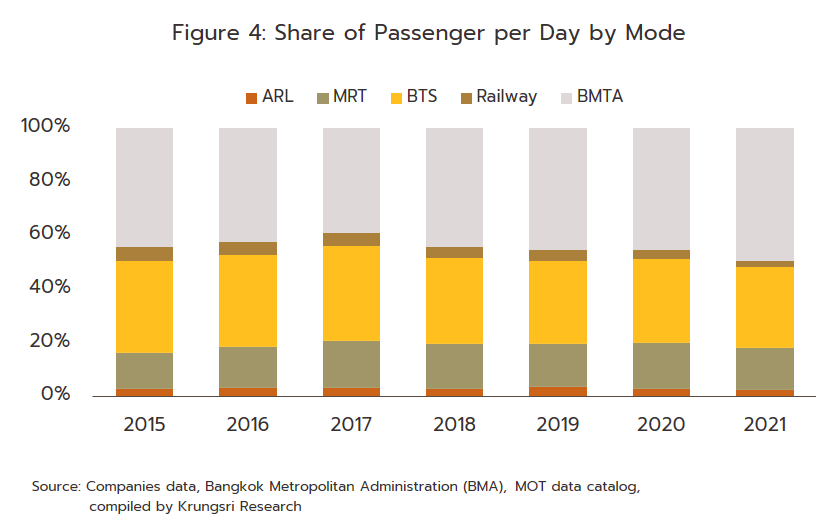

The metro system provides travelers with a reliable option for reaching the center of the city quickly and conveniently. Thanks to the build out of extensions and interchanges, the network is now reasonably extensive and its increasing reach means that in future, ridership and market share can be expected to rise steadily. Nevertheless, thanks to their lower cost and greater area coverage, bus services operated by the BMTA and by private-sector players currently have higher usage rates.

SITUATION

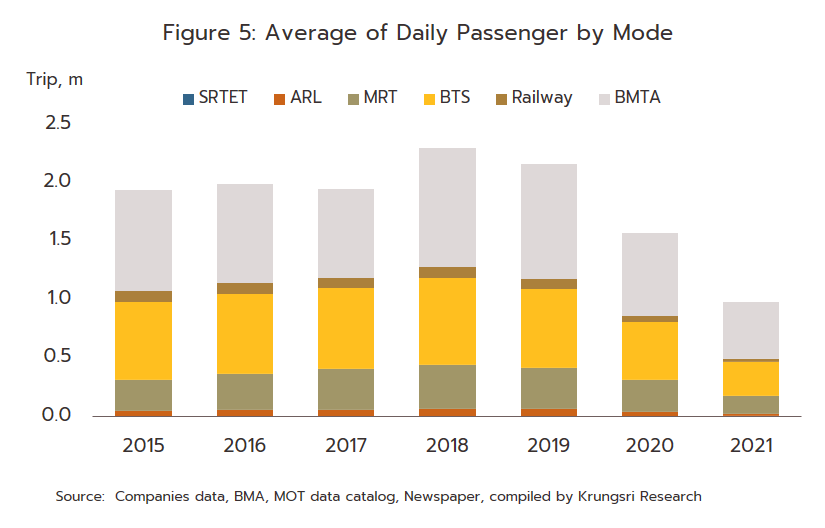

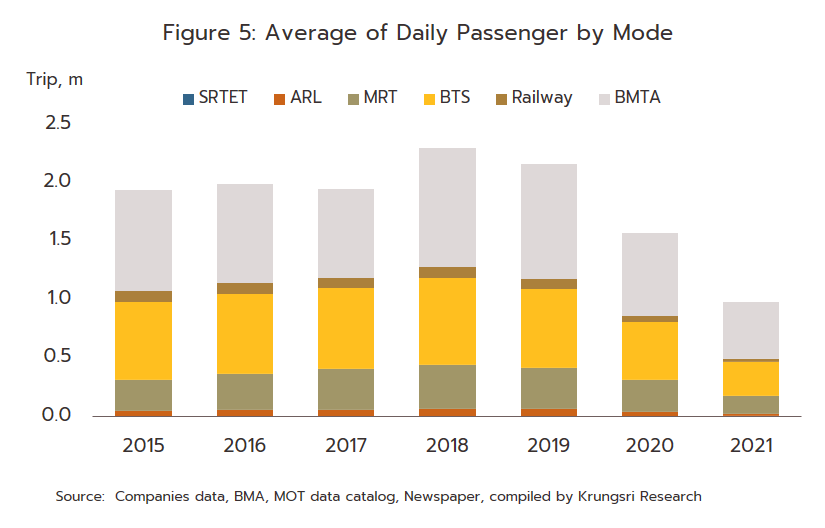

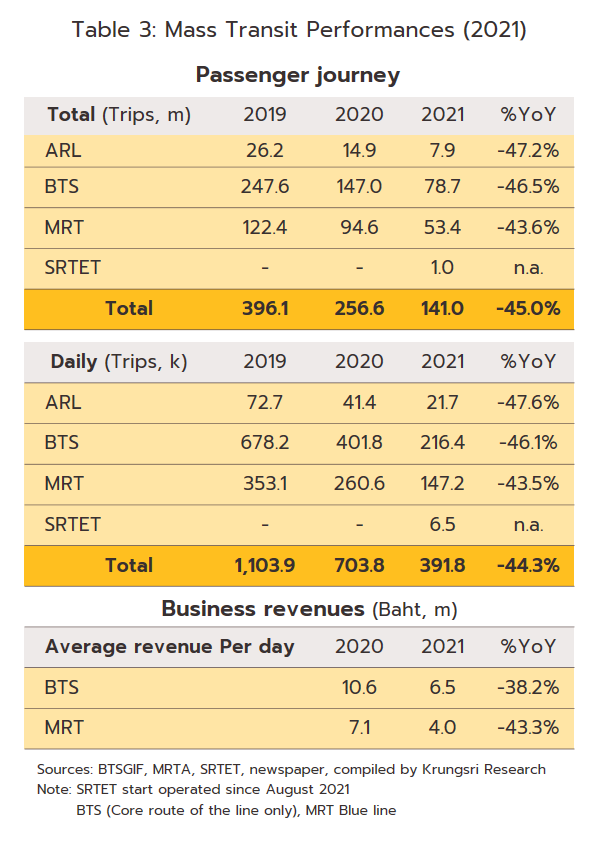

The multiple waves of COVID-19 that washed over Thailand in 2020 and 2021 had dramatic consequences for operators of Bangkok’s mass transit systems (Figure 5). Ridership was severely affected by the imposition of periodic lockdowns, the maintenance of social distancing rules, and the call for individuals to work and study at home in as much as this was possible, all of which took place against a backdrop of an extremely sharp economic slowdown that significantly eroded consumer spending power. For their part, operators also rapidly adjusted their services to meet government-imposed controls. These included reducing the hours during which metro services ran (in response to the imposition of a curfew), limiting passenger density within carriages (to meet new social distancing standards), and cutting the frequency of services to match reduced demand. As such, ridership slipped to a historic low in the third quarter of 2021, dropping -72.1% YoY to 10.7 million trips; this happened during a period when new COVID-19 cases were running at over 20,000 per day.

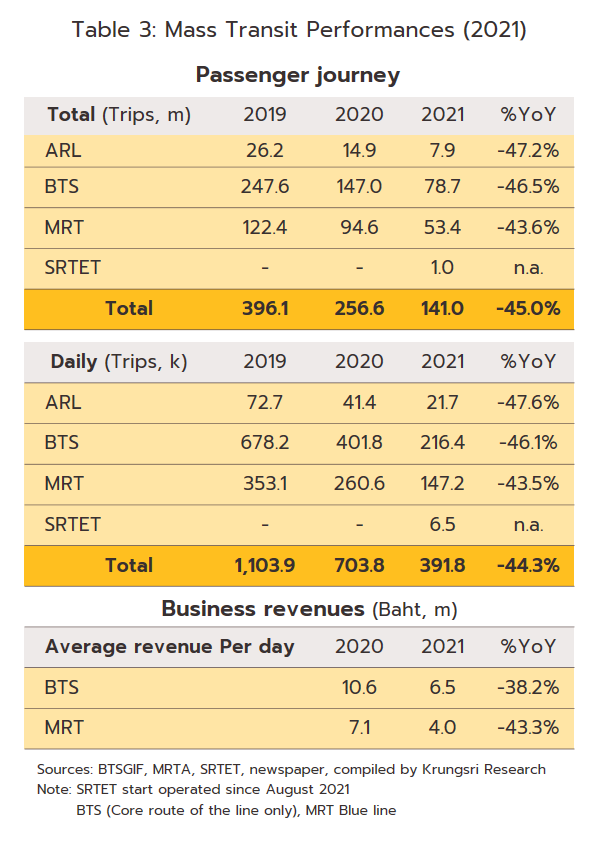

The situation improved in the last quarter of 2021 with a rebound in passenger numbers. This was driven by the success of the vaccination program, and with 64 million jabs administered in December alone, the government was able to begin relaxing pandemic controls. This included extending the opening hours of department stores, shopping centers, hotels, and cinemas (from October 16), shortening and then lifting the curfew ( October 31), and beginning to reopen the country to foreign arrivals (from November). As such, the consumers increasingly began to go out and engage in public activities again. In addition, extensions to the suburban Light Red (Bang Sue-Taling Chan, with 4 stations) and Dark Red (Bang Sue-Rangsit, with 8 stations) lines were opened, and because these connected to respectively the MRT Blue and Purple lines, this helped to increase overall demand for the travel network. Details of the situation for 2021 are given below (Table 3).

-

A total of 141.0 million trips were made on the entire mass transit system in 2021, down -45.0% from 2020. Use fell for the BTS (55.8% of all trips within the system) by -46.5% to 78.7 million trips, for the MRT, its 94.6 million trips (9.2% of the total) fell -43.6%, and the ARL, whose 7.9 million trips (8.8%) were down -47.2%. The SRTET Red Line began testing in August and commercial operations commenced in November, and in this period, it managed to register 1 million trips, 2.6% of the total.

-

Average daily passenger numbers were down -44.3% YoY to 390,000/day. On the BTS, daily usage was down -46.1%, with falls broadly similar on the MRT (-43.5%) and the ARL (-47.6%). In its almost four months of operation, the SRTET Red Line averaged 6,500 trips/day.

-

Average daily income from passenger fares for core route of the main lines dropped -40.2% YoY on a combination of the fall in passenger numbers and frequency of travel, and government policies on fares that aimed to help the traveling public. For the MRT (Blue Line) fare income was down -43.3% YoY while on the BTS (Green Line), the decline was slightly less harsh at -38.2% YoY, partly thanks to additional income from the Green Line extension. Income from advertising and the management of commercial space in stations also contracted in the year as landlords were caught between cutting rents to keep commercial space occupied and the loss of income from those who had to give up their leases entirely.

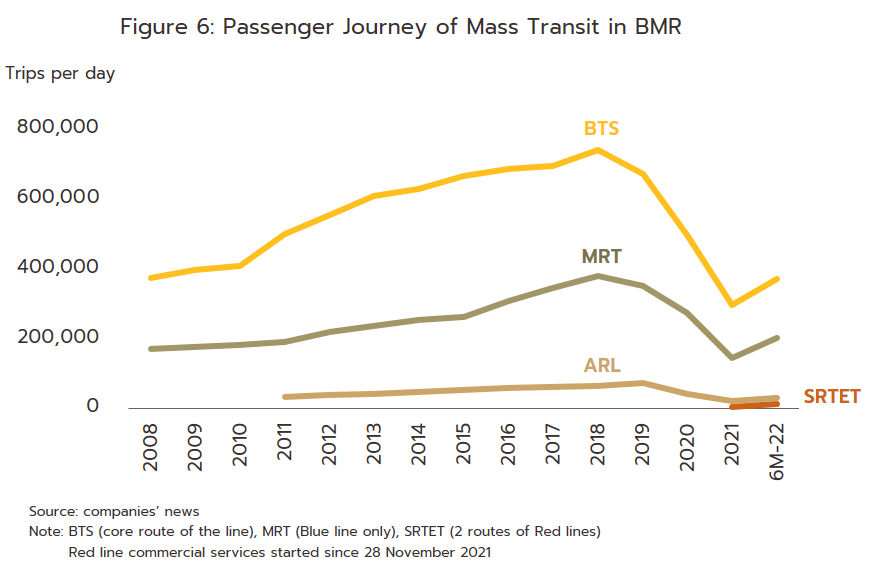

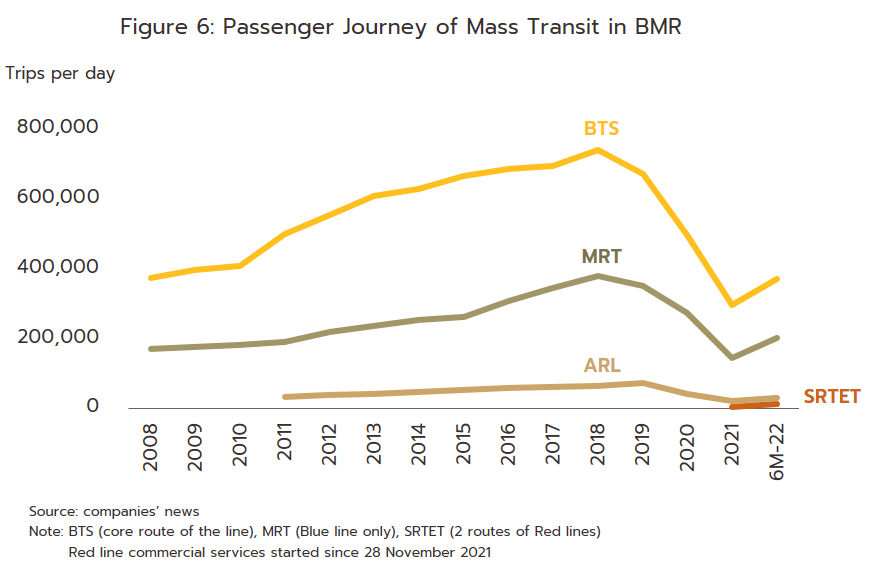

For providers of mass transit services, the situation improved through the first half of 2022 relative to a year earlier but unfortunately high rates of infection with the omicron COVID-19 variant continued to encourage travelers to stay away from public transport (Figure 6). At the same time, the surge in energy costs fed through into rising prices for goods and services and this dragged on consumer spending power with negative consequences for operators’ income. More positively, though, as of June 2022, 69.5 million COVID-19 jabs had been administered, while from May 1, the government suspended the Test & Go system, thus heralding the full reopening of the country to foreign tourists. Thanks to these moves, 2.1 million foreign arrivals were recorded in the period, up from just 0.04 million in the first half of 2021, while government stimulus spending (e.g., phase 4 of the We Travel Together program) also helped to boost the market for domestic tourism. Beyond this, the Ministry of Public Health declared COVID-19 an endemic illness and announced its plans for the transition to a post-pandemic environment, and the net effect of these factors was to increase public confidence in the use of the mass transit system.

Operators have responded to the emergence of COVID-19 by overhauling their services, both to make these easier to access and to bolster public confidence. These moves have thus included introducing measures to ensure that high standards of public health are maintained in stations and carriages and using credit cards or cashless payment systems to pay for tickets. On some lines, operators have also boosted demand by holding their fares unchanged. Details of the overall business conditions are given below.

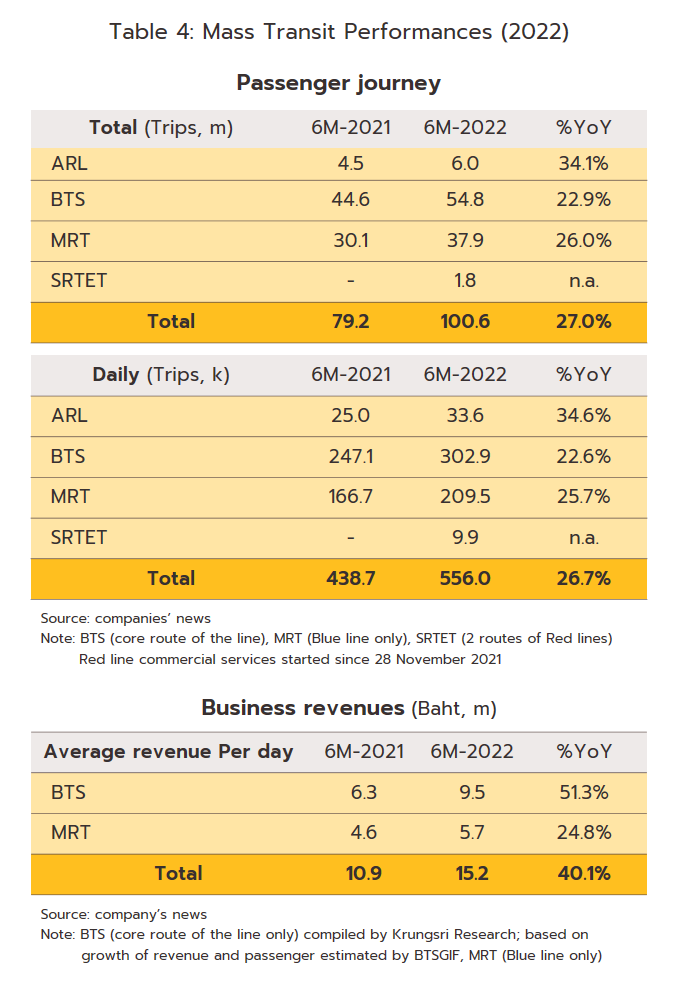

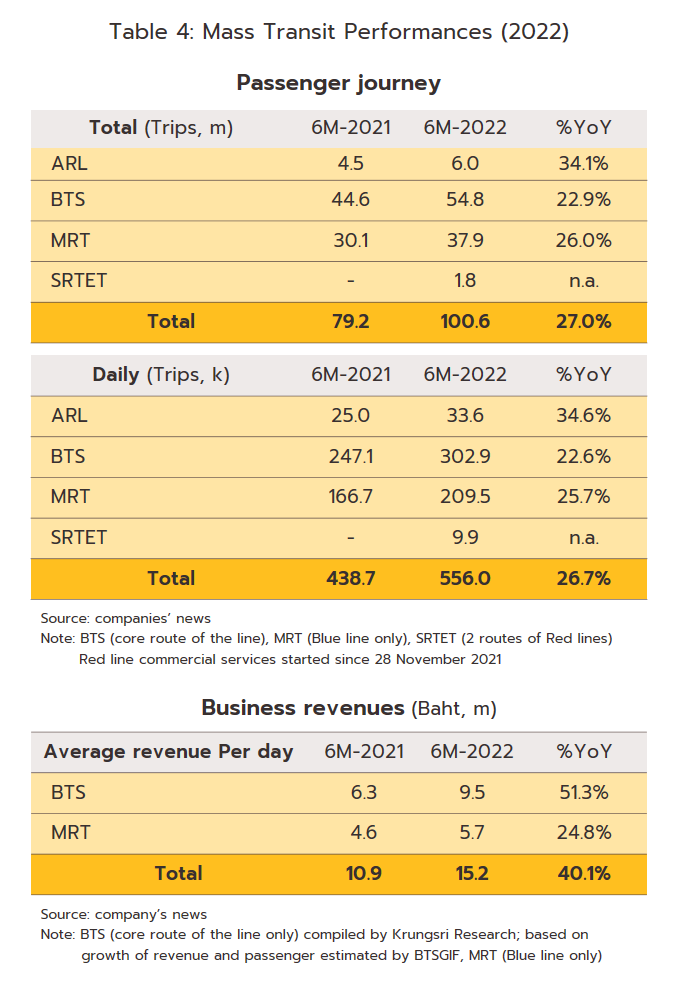

-

Ridership increased 27.0% YoY to 100.6 million trips. This jumped by 22.9% YoY to 54.8 million trips for the BTS (responsible for 54.5% of all trips on the mass transit system), by 26.0% YoY to 37.9 million trips for the MRT (37.7% of the total), and by 34.1% YoY to 6.0 million trips for the ARL (6.0%). In the period, the SRTET Red Line also reported carrying 1.8 million trips (1.8% of the total).

-

Daily usage rates also rose 26.7% YoY to 560,000 trips/day. This was led by the BTS, with 300,000 trips/day (up 22.6% YoY), followed by the MRT with 210,000 trips/day (+25.7% YoY), the ARL with 34,000 trips/day (+34.6% YoY), and the SRTET Red Line, which carried 9,900 trips/day.

-

Average daily income from fares (for the main lines only) jumped 40.1%, split between increases of 51.3% YoY for the BTS Green Line and 24.8% YoY for the MRT Blue Line.

OUTLOOK

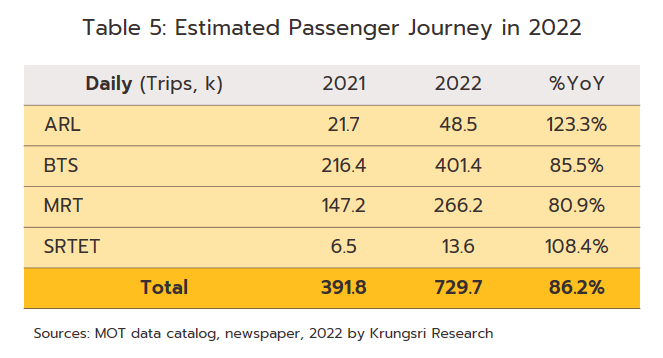

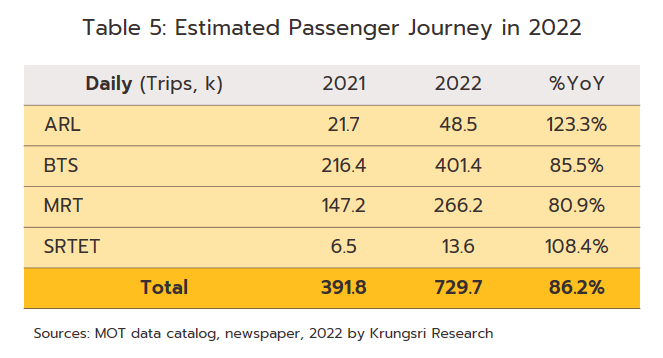

For all of 2022, average daily ridership across the network is expected to increase 86.2% YoY to 730,000 trips/day. This will work out as 400,000 trips/day for the BTS (+85.5%), 270,000 trips/day for the MRT (+80.9%), 49,000 trips/day for the ARL (+123.3%), and 14,000 trips/day for the SRTET Red Line (+108.4%). Use of mass transit services will tend to strengthen in the latter half of the year, helped by several factors. (i) Government controls on economic and social activities are being lifted, largely thanks to progress on vaccinating the population (170 million doses will be administered in 2022[10]) and the fact that members of the public are now able to buy COVID-19 treatments themselves. With this normalization of economic activity, day-to-day life is returning to normal, meetings and seminars are going ahead as planned, and work and education is increasingly taking place on-site again. This is then adding to demand for mass transit services since these offer a convenient way of integrating travel in inner and outer parts of Bangkok. (ii) The abandoning of the Thailand Pass and the lifting of health insurance requirements for foreign arrivals (with effect from July 1, 2022) is helping to boost the tourism sector and so over 10M22, 7.6 million arrivals were recorded. This is expected to increase to 10.4 million for the year as a whole, compared to just 0.43 million in 2021. (iii) Global oil prices are expected to remain high (Dubai crude will average USD 98/bbl for 2022, up from USD 69/bbl in 2021) and this will encourage greater use of the metro in place of private vehicles. (iv) This will be the first year that the entire Green Line is open to the public along all of its 60 stations. This will therefore make travel considerably easier for individuals moving along the Bangkok-Samut Prakan-Pathum Thani line, adding to demand that has already been boosted by the reopening of the Queen Sirikit National Convention Centre in September.

Service operators’ income will tend to continue to grow on rising passenger numbers, though these remain very weak compared to the 2019 pre-COVID-19 average of 2.79 million trips/day. At present, the rebound in numbers is being constrained by weak and fragile consumer spending power and the rising cost of living, itself a consequence of the impact of the prolonged Ukraine-Russia war on global energy prices.

Over 2023-2025, mass transit usage rates will return to close to their 2019 level.

-

Total ridership is forecast to increase by an average of 18.9% annually. For individual operators, the annual increase will work out as 19.8% for the BTS, 15.7% for the MRT, 24.0% for the ARL, and 35.1% for the SRTET Red Line.

- Average daily passenger numbers will increase at the slightly slower rate of 16.7% per year, or by 22.0% for the BTS, 11.6% for the MRT, 16.4% for the ARL, and 22.5% for the SRTET Red Line. Likewise, on the core lines, average daily income from passenger fares will be up 20% annually, split between 22% for the BTS Green Line and 18% for the MRT Blue Line (the MRT is keeping fares unchanged until July 2023 while the BTS starts to increase fares from January 2023).

Major factors underpinning a brightening of the business outlook over the next few years will include the following.

-

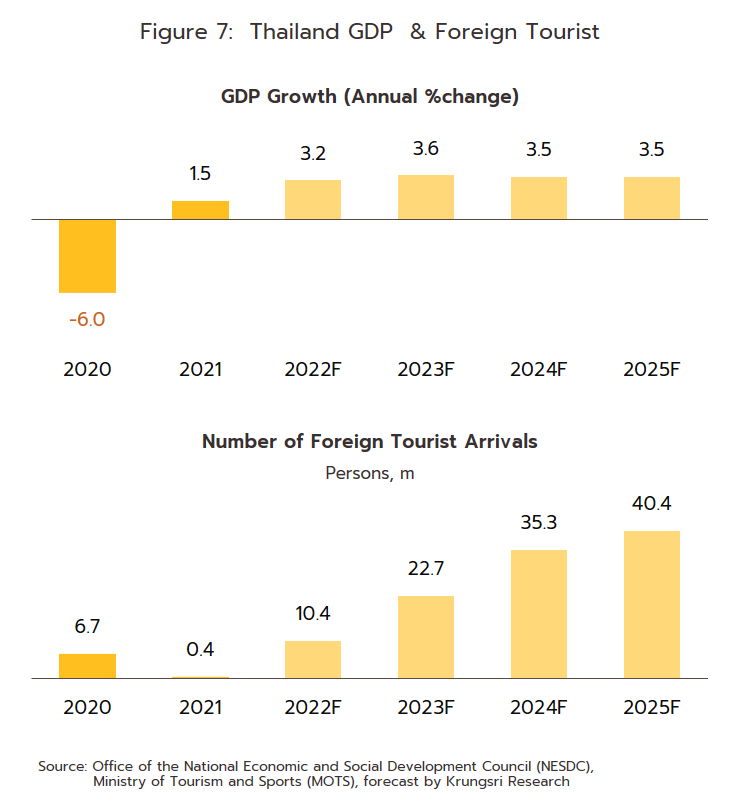

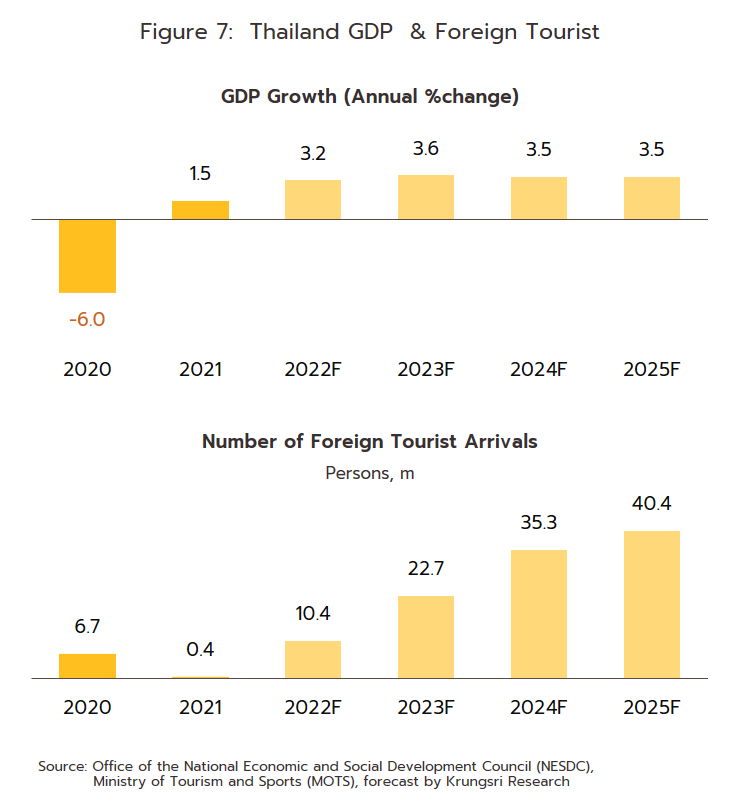

Average annual economic growth of 3.0-4.0% will lift consumer spending power, and so private-sector consumption is expected to expand by 4-5% per year over 2023-2025. At the same time, recovery in the tourism sector is forecast to bring total foreign arrivals to 22.7 million, 35.3 million, and 40.4 million in each of the next three years (Figure 7).

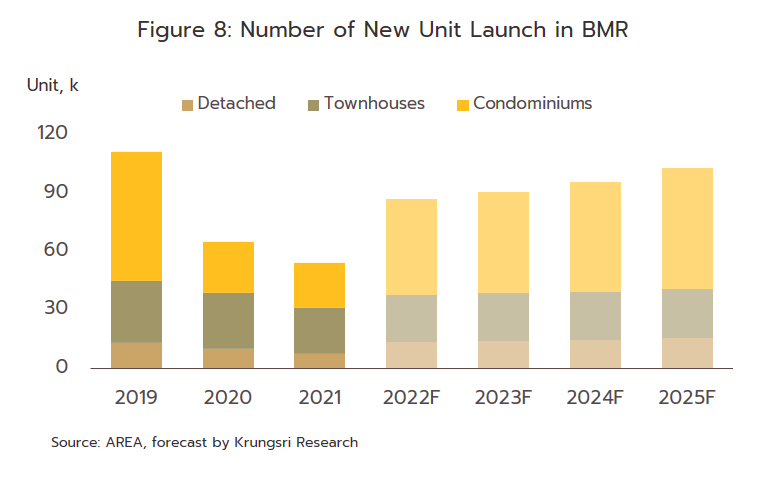

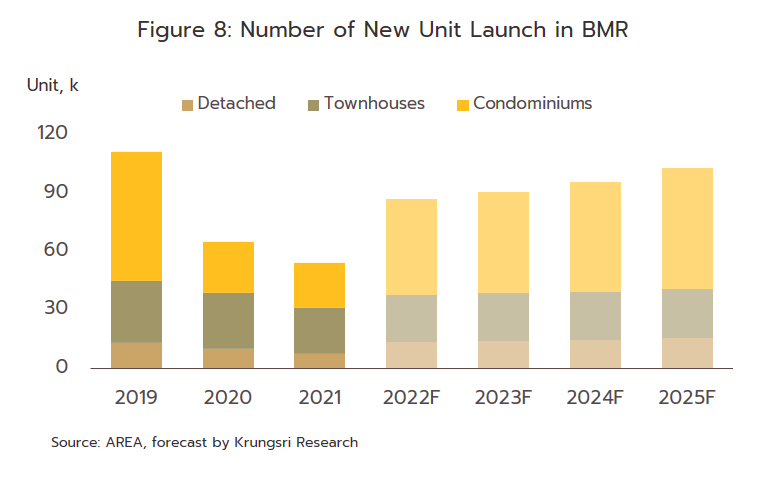

- The government’s investment on new infrastructure is helping to crowd in additional investment in new residential accommodation. This is particularly so with regard to extensions to the mass transit system, and new real estate developments are quick to sprout in areas within reach of these new lines. The new generation of home buyers also shows a marked preference for low-rise accommodation that is situated close to mass transit lines since this allows them to avoid problems with traffic congestion. This preference is reflected in DDproperty’s July 2022 Thailand Consumer Sentiment Study, which revealed that for 51% of respondents, easy access to public transport was one of the most important factors influencing future decisions about accommodation. As regards the supply of this, Krungsri Research estimates that over 2023 to 2025, the number of new low- and high-rise properties will expand by around 5-8% per year, with some 97,000 new units thus coming to market annually (compare with the average of 100,000 new units released per year over 2014-2019) (Figure 8). This will then add substantially to the number of passengers on mass transit lines.

-

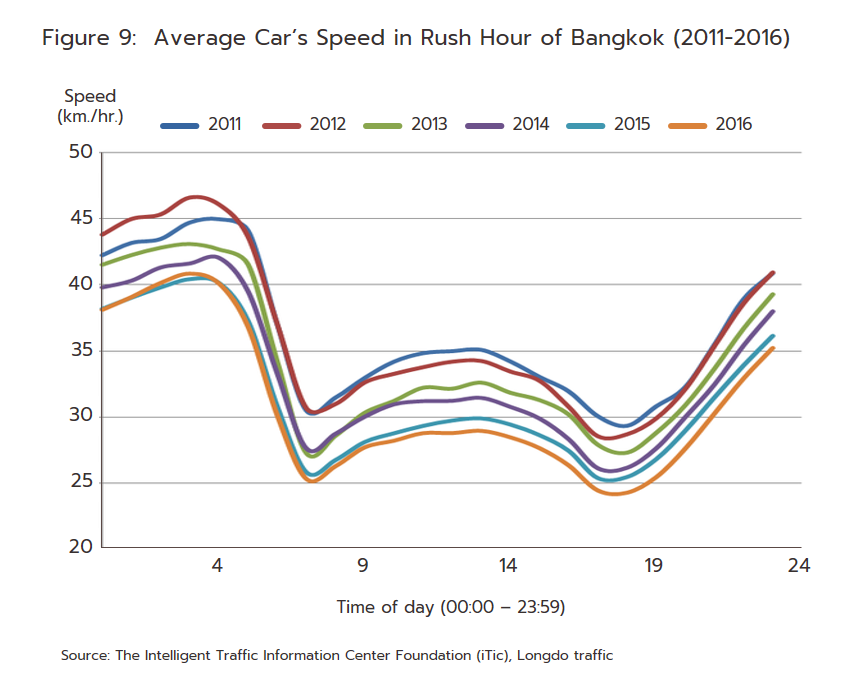

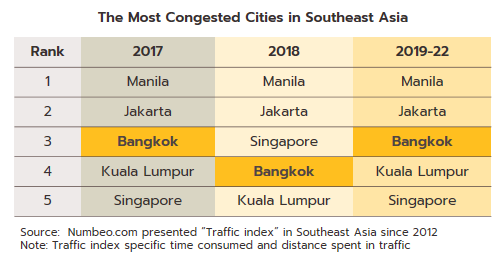

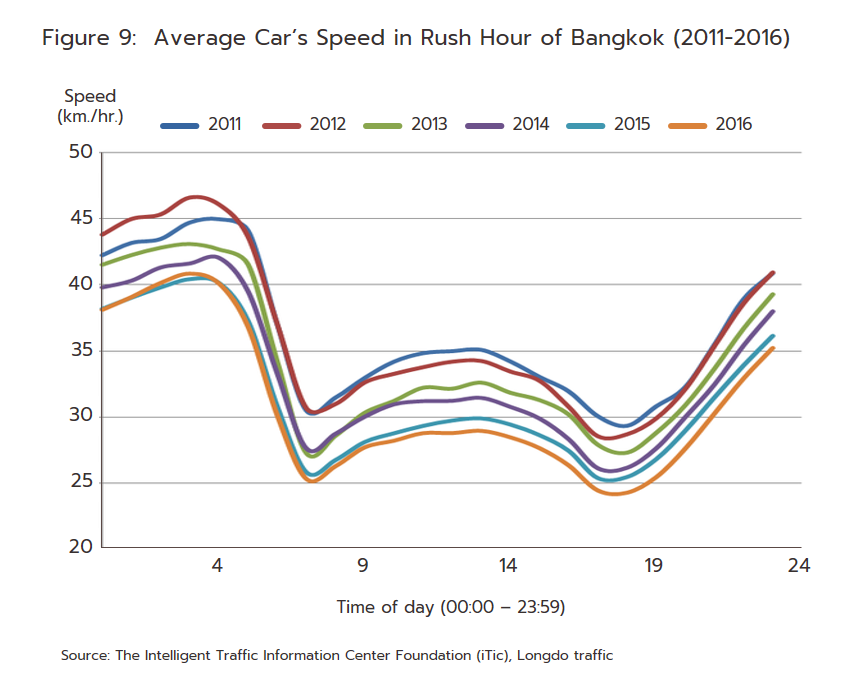

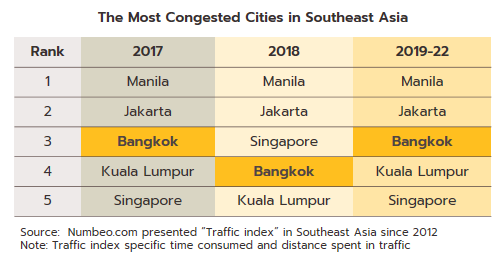

Consumers are expected to adjust their behavior in the coming period and to make greater use of mass transit systems since these offer passengers a reliable, quick, and convenient means of traveling into the center of the city. Lines that connect to other feeder networks will likely prove to be especially popular. These will include the Red Line (Bang Sue-Rangsit and Bang Sue-Taling Chan), which connects to suburban rail lines and diesel-powered stock at the Taling Chan interchange (Thonburi-Taling Chan-Nakhon Pathom) and with the Blue Line at Charan Sanit Wong station. Likewise, traveling on the Gold Line gives passengers the opportunity to change to the Green Line at Krung Thonburi and the riverside feeder connecting to river transport on the Chao Phraya. Additional demand for mass transit services will be driven by the rising number of cars in particular within the BMR, where this will help to keep average car speeds during morning and evening rush hour at their already extremely low level, or possibly even worsen the situation11/. This is, unfortunately, not a new development, and average rush-hour road speeds fell every year over the period 2011 to 2016 (Figure 9).

-

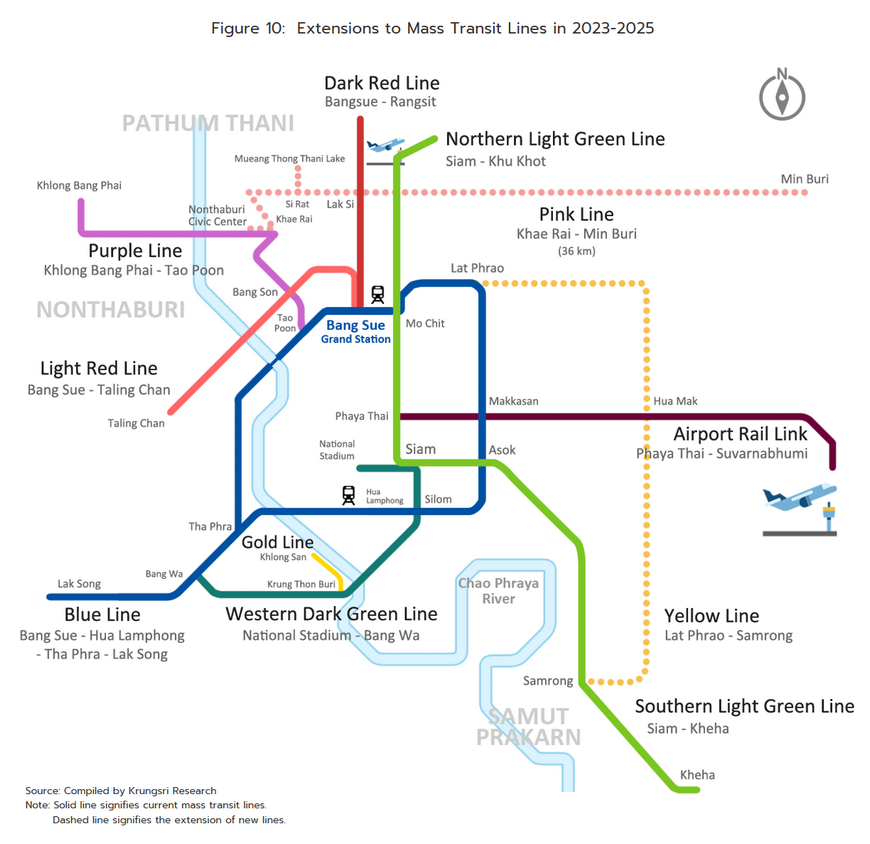

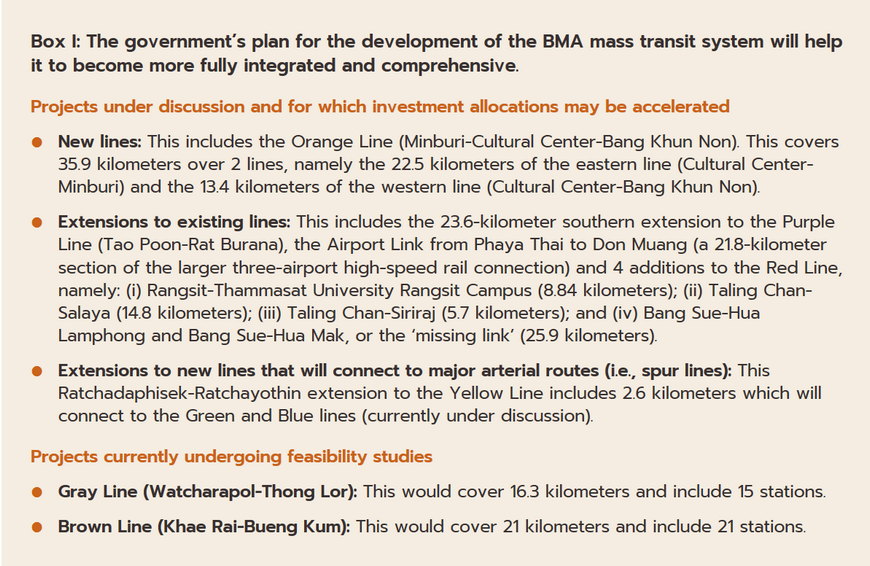

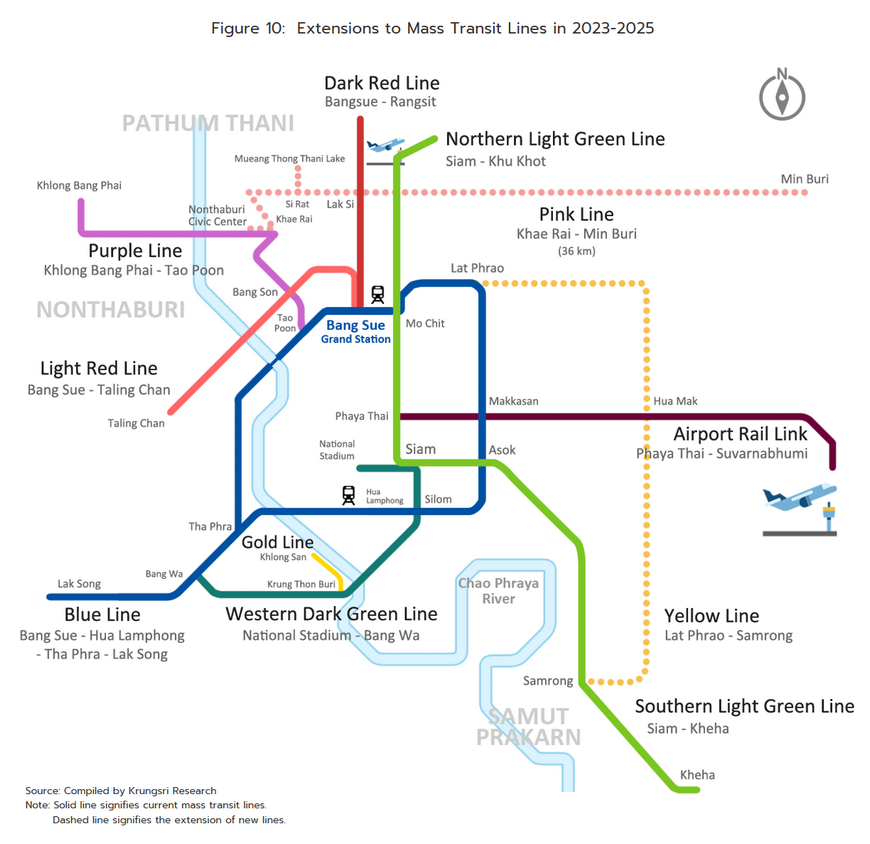

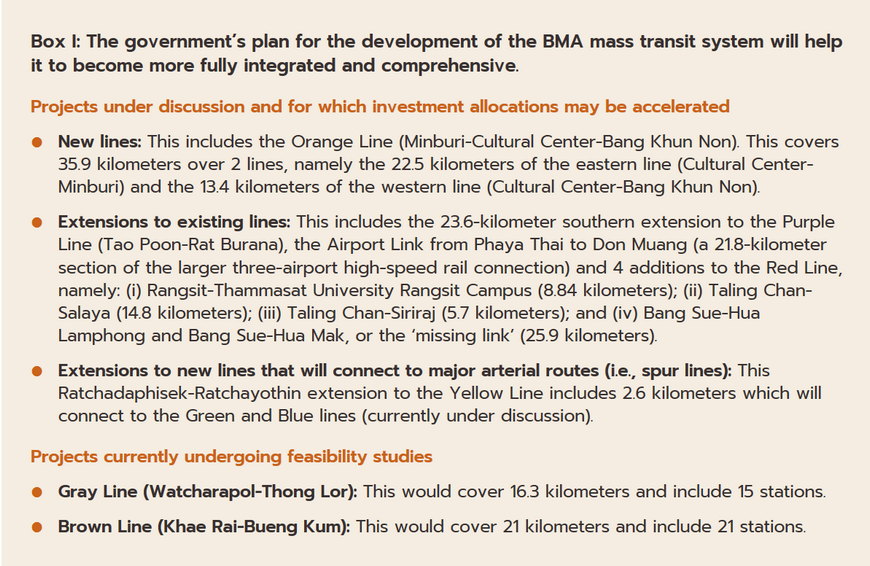

The government plans to build new lines, extend existing routes, and expand the number of interchange stations, and this will increase the number of stations within the network and further its reach. Once trains are running on these new lines and the extensions have become fully operational, the increasing number of connections and broadening of travel options within the metro network will add to passenger numbers on older routes. In addition, the development of other public transport modalities and their integration into the metro system will also boost demand (e.g., through feeder systems such as river buses, regular and shuttle buses, and bicycle-sharing schemes), add to the system’s overall convenience and efficiency, and help it carry greater numbers of passengers. New lines that should come into operation over 2023-2025 include the following (Figure 10):

-

Pink Line (Khae Rai-Minburi): This runs for 34.5 kilometers through 30 stations. Testing and trial runs, during which travel will be free of charge, for Minburi-Chaeng Watthana Government Complex section (19 stations, covering 21.5 kilometers) will begin in July 2023, with full commercial operations for the whole line expected to commence in August 2023.

-

Extension of Pink Line (Si Rat-Muang Thong Thani): This extension includes 3 stations and covers 2.8 kilometers to the Pink Line. The commercial service will start in 2025.

-

Yellow Line (Lat Phrao-Samrong): Trial runs of this line, which includes 23 stations and covers 30.4 kilometers of track will start in May 2023, and full commercial operations should commence in June 2023.

Operators are moving rapidly to increase passenger safety by adopting cashless payment systems (Europay Mastercard and Visa contactless) and then linking these between trains managed by the MRTA, suburban trains, river buses, and BMTA and Bus Transport Company buses. This will help to make travel much more seamless for passengers switching between these, and it is expected that the system will come online in 2023.

The government is providing ongoing support for investment in the expansion of the mass transit network and the construction of new lines, with the goal of providing an integrated, comprehensive travel network for the BMR. Corporations already playing a role as mass transit service providers thus have the opportunity to step up their investments. This will then allow them to generate additional income from operating mass transit lines (i.e., from passenger fares and from fees for the maintenance and repair of equipment) and from connected services (i.e., from managing commercial space for advertising, the use of communications equipment, or as rental units) in carriages and in and around stations.

[1] Mass transit systems are defined as transport systems that move large numbers of passengers along fixed routes according to predetermined schedules. In Thailand, land-, air- and water-based mass transit systems are operated, although land-based services (including rail) are the primary means of travel. These services include: (i) buses, both standard types and minibuses, (ii) rail transport, including suburban railways (operated by the State Railway of Thailand) and the MRT (a joint public-private initiative).

[2] According to the Numbeo Traffic index, Bangkok is one of the 5 worst cities in Southeast Asia for traffic congestion.

[3] According to its administrative arrangements, Bangkok can be divided into three zones. (i) The inner zone is composed of Phra Nakhon, Pom Prap Sattru Phai, Samphanthawong, Pathum Wan, Bang Rak, Yan Nawa, Sathon, Bang Kho Laem, Dusit, Bang Sue, Phayathai, Ratchathewi, Huai Khwang, Khlong Toei, Jatujak, Thonburi, Khlong San, Bangkok Noi, Bangkok Yai, Din Daeng and Watthana. (ii) Further out is the middle or central region, which includes Phra Khanong, Prawet, Bang Khen, Bang Kapi, Lat Phrao, Bueng Kum, Bang Phlat, Phasi Charoen, Chom Thong, Rat Burana, Suan Luang, Bang Na, Thung Khru,Bang Khae, Wang Thonglang, Khan Na Yao, Saphan Sung and Sai Mai. (iii) Finally come the outer, suburban districts of Minburi, Don Muang, Nong Chok, Lat Krabang, Taling Chan, Nong Khaem, Bang Khun Thian, Lak Si, Khlong Sam Wa, Bang Bon and Thawi Watthana.

[4] Krung Thep Aphiwat Central Station also called Bang Sue Central Station. This is a local rail hub that connects the suburban Red Line, longer distance trains, and the Airport Rail Link. In the future, this will also include new high-speed rail lines. The 4 extensions under consideration are all public-private ventures and include: (i) Rangsit-Thammasat University Rangsit Campus (8.84 kilometers, and 4 stations); (ii) Taling Chan-Salaya (14.8 kilometers, and 9 stations); (iii) Taling Chan-Siriraj (5.7 kilometers, and 3 stations); and (iv) Bang Sue-Phaya Thai-Makkasin-Hua Mak-Hua Lamphong (25.9 kilometers, and 9 stations).

[5] Under the Private Participation in State Undertaking Act of 2013, development of the urban metro system is one of the permitted areas under which public-private partnerships are currently permitted.

[6] Stages of the project at which the private sector may choose to invest and participate include laying foundations for the project, construction and civil engineering works, instillation of the electrical system and/or machinery, supplying the rolling stock, operating it, managing commercial space in and around stations, and undertaking maintenance of trains and the system’s equipment. If the private sector operator that wins the bidding for the concession chooses to invest at these various stages, it will generate profits from a range of different sources, including fees for demolition, construction work or civil engineering, income from the installation of equipment, charges for managing the system, fees for providing services to maintain electrical systems and equipment, and charges collected from travelers and tenants for the commercial development of land at stations (e.g., renting out advertising or retail space, or leasing access for the installation of communications equipment).

[7] The division of returns specified in contracts may include additional conditions, such as that the share of income may increase after a set period of time (every 10 or 15 years, for example) or that the burden of bearing some costs should be eased (e.g., that maintenance costs should be cut at a fixed rate every 5 years.)

[8] The Mass Rapid Transit Master Plan in Bangkok Metropolitan Region (or M-Map) is the master plan for the development of the area’s metro system over 2010-2029, and this covers work on a total of 14 lines.

[9] The central business district (CBD) is an area that is dominated by business activities and which is physically located in the easy-to-reach center of the urban region. The CBD is usually densely populated and so the expansion of buildings tends to occur vertically. In Bangkok, the CBD comprises Silom, Sathorn, Surawong, Rama 4, Ploenchit, Wireless Road, Sukhumvit (Sois 1-71) and Asoke.

[10] This estimate is based on the 142.85 million doses that had been administered as of September 5, 2022 and the 31.6 million individuals who had been triple-jabbed as of August; 25 these are expected to have another jab by the end of the year, as per the subcommittee on immunology’s recommendations that individuals should have a booster every 4 months.

[11] The Office of Transport and Traffic Policy and Planning (OTP), the Thai Intelligent Traffic Information Center Foundation (iTIC), and Longdo.

.webp.aspx)