Executive summary

The Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA) is a global project that aims to increase the sustainability and lessen the environmental impacts of the aviation industry. The scheme has two principal components: (i) measuring, reporting and verifying (MRV) carbon emissions arising from international aviation; and (ii) offsetting emissions in excess of agreed quotas through the purchase of carbon credits. The Thai aviation sector has been covered by the CORSIA scheme since 2021, though in its initial stages, the impacts on industry have been only slight. However, enforcement will begin in earnest in 2027, and with almost all emissions from international flights counted against baselines, carriers’ overheads are certain to rise. Indeed, by the end of CORSIA’s second phase in 2035, the cost of the carbon credits required by Thai airlines to offset an anticipated 40 million tonnes of excess CO2 emissions is likely to run to some THB 20 billion. More positively, though, the CORSIA project will help to stimulate growth in markets for the high-quality carbon credits required as offsets as well as for sustainable aviation fuels (SAFs), which will help to reduce the need for these offsets in the first place. More broadly, the enforcement of the CORSIA regulations will also encourage the country to develop its MRV system, to cut its aviation-related emissions, and to further expand the scope and quality of investments in the environmental projects used to generate high-quality carbon credits.

Aviation-related carbon emissions

Aviation is a significant contributor to total anthropogenic carbon emissions, and not only is the industry a major source of these, it is also widely recognized as a ‘hard-to-abate’ sector, that is, decarbonizing aviation presents a particular set of challenges. Carbon emissions from flying have risen steadily over the past few decades, and in 2019, these reached around 1 billion tonnes of CO2, or 2.5% of total global emissions1/, with some 65% of this coming from international aviation2/. However, the Covid-19 pandemic dealt a severe blow to tourism worldwide and so at the start of the decade, aviation-related emissions slumped, but with the ending of the crisis and the rebound in the tourism sector from 2022 onwards, these have begun to climb again. Emissions are therefore now back to 80% of their pre-Covid level3/.

In 2022, the member states of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) joined together to lay out their ‘long-term global aspirational goal’ of transitioning international aviation to net zero carbon emissions by 2050 (the so-called ‘fly net zero’)4/. However, reaching this goal will depend on successfully orchestrating operations both inside and outside the industry. This will include increasing investment in new aviation technology, supporting the increased production and consumption of sustainable aviation fuels (SAFs), and using carbon credits to offset ongoing emissions from aviation with cuts made elsewhere in the economy. Introducing the market-based measure known as the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA), it is hoped to help move the industry much closer towards the goal of full sustainability, particularly over the short to medium term, when it will remain challenging to achieve rapid cuts in emissions through efficiency gains and technological advances.

CORSIA: A mechanism for measuring, reducing, and offsetting international aviation emissions

What is CORSIA?

The CORSIA agreement specifies a framework under which airlines around the world will be required to use carbon credit markets to offset greenhouse gas emissions when these cannot be reduced through technological innovations, operational efficiency gains, or the use of sustainable aviation fuels. The ICAO began the phased roll out of the CORSIA program in 2016, and from 2019, measurement and reporting of emissions has been required for all airlines operating in the 193 ICAO member states. Data gathered at this initial stage will be used to set targets for reductions and offsets that will be enforced at subsequent stages of the scheme.

In brief, CORSIA is thus a global mechanism for ensuring that carriers monitor and report carbon emissions resulting from international aviation and then reduce or offset these appropriately, and so it is hoped that the program will play an important role in decarbonizing the aviation industry.

CORSIA requirements

CORSIA imposes two main requirements on airlines: (i) monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) of greenhouse gas emissions; and (ii) offsetting emissions resulting from international aviation. These two aspects of the scheme are explained in more detail below.

1) MRV requirement

The CORSIA requires airlines and airplane operators that fly on international lines, that are responsible for more than 10,000 tonnes of CO2 emissions annually, and that use aircraft weighing more than 5,700 kg to undertake comprehensive MRV of these flights. This requirement came into force in 2019, with companies estimating greenhouse emissions through the ICAO’s Fuel Use Monitoring Method. Alternatively, airlines covered by CORSIA but releasing fewer than 50,000 tonnes of CO2 annually may measure these emissions using the ICAO’s CO2 Estimation and Reporting Tool (CERT).

The assessments made by carriers then have to be verified by independent auditors licensed for this by the ICAO, which in the case of Thailand is the Management System Certification Institute (MASCI)5/. Once these have been confirmed and verified, data on carbon emissions are reported to the national civil aviation authority, which in Thailand is the Civil Aviation Authority of Thailand (CAAT). The CAAT collates data from all Thailand-based carriers and then makes an annual submission of this to the ICAO.

2) Offsetting requirement

International carriers that exceed their carbon allowance have been required to offset this through approved carbon credits since 2021. However, this is only in the case that the flight links two participating states, and if either or both the originating and destination nations are CORSIA non-participating states, offsets are not required, though MRV is still obligatory in all cases (Figure 3) Reporting and verification is an annual process, but where appropriate, offsets have to be made only every three years. There are several issues relating to the making of offsets, the three most important of which are discussed below.

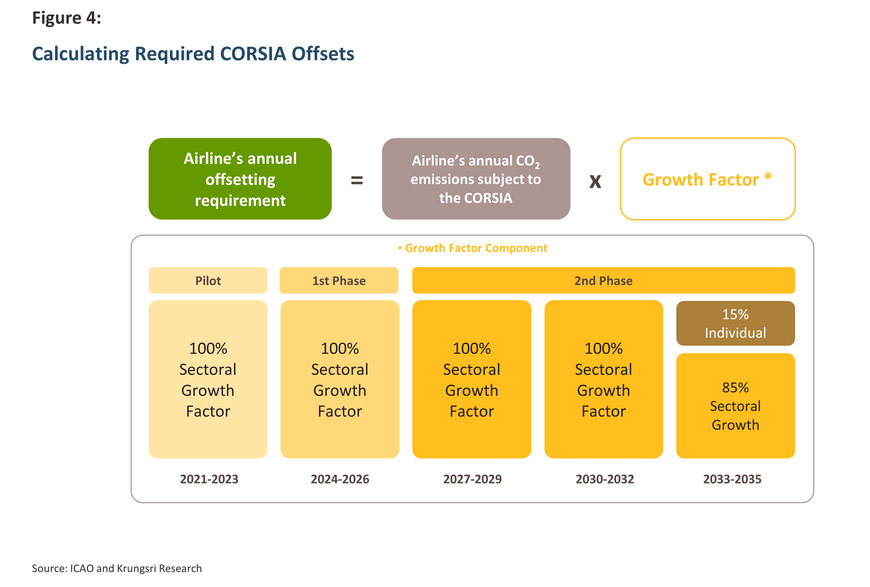

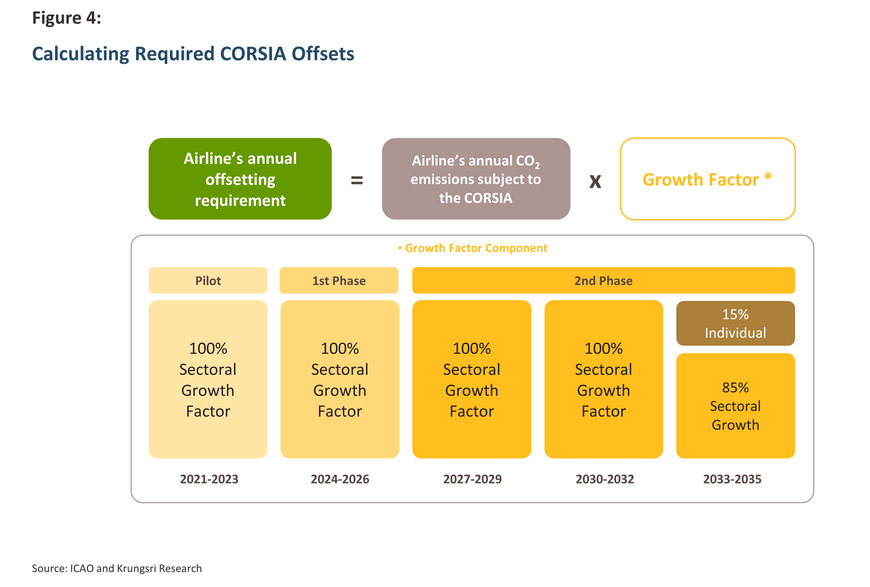

- The scale of offsets: The carbon emissions that individual airlines are required to offset is calculated from the carrier’s annual emissions multiplied by the sectoral growth factor (SGF), or the rate of growth in emissions across the international aviation industry as a whole. The ICAO calculates the latter based on an annual comparison of the data submitted to it by airlines covered by the CORSIA scheme and its assessed baseline emissions. This ensures that airlines are responsible for the costs associated with their contributions to overall emissions on a 100%-shared emissions basis. However, from 2033 onwards, this will change, and rather than being 100%-shared, 15% of the required offsets will come from the carrier’s own individual growth factor. The remaining 85% will continue to come from the SGF (Figure 4).

-

Making offsets: The ICAO’s Technical Advisory Body (TAB) requires that airlines offset their emissions through carbon credits6/ that qualify under the Emissions Unit Eligibility Criteria. Through the CORSIA pilot phase (2021-2023), 11 carbon offsetting standards7/ have been recognized by the ICAO, including the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS) and the Gold Standard (GS). However, as of a March 2024 announcement, only credits verified by the American Carbon Registry (ACR) and Architecture for REDD+ Transactions (ART) will be acceptable for Phase 1 of CORSIA implementation (2024-2026).

-

Reducing the need for offsets: Under CORSIA, airlines are able to reduce the emissions that are counted against them by switching to CORSIA Eligible Fuels (CEFs)8/. These include sustainable aviation fuel (SAF), low carbon fossil-based aviation fuel (LCAF), and non-drop-in fuels (i.e., alternative fuels that require a change to legacy airframes and fueling infrastructure, e.g., hydrogen- or electric-powered aircraft). These fuels need to be sourced from a supplier accredited under the Sustainability Certification Scheme (SCS), although currently the ICAO recognizes only two standards, namely the International Sustainability and Carbon Certification (ISCC) and the Roundtable on Sustainable Biomaterials Association (RSB)9/.

Enforcement of CORSIA

The requirements imposed by CORSIA will gradually be tightened as enforcement moves through three distinct phases.

-

Pilot phase (2021-2023): Offsets are voluntary and are calculated against the 2019 emissions baseline. The latter has been chosen because this was the most recent set of data unaffected by the Covid-19 pandemic.

-

Phase 1 (2024-2026): Offsets remain voluntary at this stage, but the obligations placed on airlines become more challenging due to the shift down in the baseline to 85% of 2019 emissions. As of 2024, 126 countries had agreed to participate in this phase of the CORSIA agreement10/. Thailand is among these participants.

-

Phase 2 (2027-2035): Offsets become obligatory for airlines operating out of ICAO member states with the exception of a small number of vulnerable or otherwise disadvantaged nations. During this phase, three rounds of offsets will be made. As in phase 1, the baseline will remain 85% of 2019 emissions, but for the final round (2033-2035), a carrier’s own Individual Growth Factor will feature in the calculations.

Impacts, opportunities and challenges arising from the enforcement of CORSIA

CORSIA has already come into effect but as the regulations are tightened in the coming years, the consequences for stakeholders in international aviation will vary.

Airline industry

Airlines will clearly be the industry most heavily impacted by CORSIA, with international carriers necessarily the most exposed part of this. Overheads will rise as a result of: (i) MRV requirements; (ii) the cost of emissions reductions; and (iii) the need to purchase carbon credits to offset greenhouse gas emissions. Although costs related to emissions reductions and offsets are somewhat limited at present, this will rise steadily once enforcement of these measures becomes obligatory in 2027.

Impacts on global airlines

Due to the effects of the pandemic through these years, Krungsri Research expects that for the 2021-2023 pilot phase, airlines operating in countries that are participating in this phase of CORSIA will not be required to purchase any offsets. The ongoing sluggishness of demand thus kept aviation emissions below the pre-Covid baseline and so for 2021 and 2022, the Sectoral Growth Factor (SGF) has been published at 0%11/.

However, airlines will begin to feel greater financial pressure during phase 1 of the scheme (2024-2026) as the abating of the pandemic helps sectoral recovery to gain speed and the emissions baseline is reduced to 85% of its 2019 level. Given this, the offsets required to meet phase 1 obligations are expected to total 150 million tonnes of carbon dioxide (MtCO2), implying additional costs to the industry of some USD 1.5 billion. The total costs imposed by CORSIA will continue to grow as the industry expands and more countries (and thus their airlines) join the agreement, such that by 2035 and the completion of the current arrangements, demand for offsets is expected to come to more than 1,500 MtCO212/. Purchasing these carbon credits will cost airlines around USD 23 billion, or according to ICAO estimates, 0.4%-1.4% of all income accruing to airlines.

Other factors affecting the costs of participation in CORSIA will include the price of CORSIA Eligible Credits and the adoption of SAFs and other CORSIA Eligible Fuels to make inroads into total emissions. At present, use of SAFs is expected to contribute USD 80-530 million in savings towards the cost of required offsets13/.

In addition to the cost of purchasing offsets, airlines will also have to shoulder the additional overheads entailed in meeting the CORSIA MRV requirements, which the ICAO sees totaling USD 110-540 million14/ (or THB 4-20 billion) across the global industry over 2018-2035. Around 70% of these costs will have to be borne by medium- and large-sized carriers since these will not be able to take advantage of the ICAO’s simplified CO2 Estimation and Reporting Tool (CERT), and will instead have to invest in upgrading their own MRV capabilities. However, verification costs will be a significant new overhead for carriers of all sizes, especially given the fact that only companies licensed by the ICAO will be able to fulfill this role.

Impacts on Thai airlines

Since 2021, Thailand has been among the eighty-eight countries participating in the CORSIA pilot phase, and so from 2022 onwards, the Civil Aviation Authority of Thailand (CAAT) has required Thai airlines to report their fuel consumption and statistics relevant to their flights. In addition, carriers operating aircraft on international flights that weigh more than 5.7 tonnes also now need to estimate and report their annual carbon emissions15/. At present, seven Thai carriers are covered by CORSIA, namely: Thai Airways, Bangkok Airways, Thai AirAsia, Thai AirAsia X, Thai Lion Air, Thai VietJet Air, and K-Mile Air16/ (Figure 6).

2019 emissions by Thai airlines (combined outbound and inbound) on international lines totaled around 11 MtCO2, or some 2% of all emissions attributable to international flights. In the pre-Covid period (2015-2019), Thai airlines’ emissions grew at an average rate of 4.3%17/. With the country included in all phases of the CORSIA scheme, Krungsri Research thus expected the impacts of its enforcement to vary over time.

-

Pilot phase (2021-2023): The Covid pandemic delivered a body-blow to the airline industry and although recovery set in over 2022 and 2023, activity has yet to return to its pre-pandemic level. Data from the Civil Aviation Authority of Thailand thus show that in 2023, Thai carriers made a combined total of 0.12 million international flights to and from Thailand (25.9% of all Thailand’s inbound and outbound international flights), down from 0.2 million in 2019 (when Thai carriers were responsible for 29.3% of all flights in and out of Thailand). The Thai airline industry has thus yet to recover fully, and indeed the pace of growth continues to lag behind the rebounds seen in many other countries. In light of this, carbon emissions are expected to stay below the baseline through the pilot phase and so it will not be necessary for Thai carriers to buy additional offsets.

-

Phase 1 (2024-2026): From 2024 onwards, the financial costs connected to CORSIA will begin to become a reality as international travel continues to recover, the emissions baseline is adjusted down, and more states participate in the scheme. Currently, 126 countries are covered by the program, and in 2023, around half of all Thailand’s international flights will count towards the country’s CORSIA obligations (i.e., flights between CORSIA State Pairs), up from 40% in 2019. In terms of raw flight numbers, the five most important destinations for Thai carriers are Singapore, Cambodia, Japan, Malaysia and Indonesia, respectively (Table 3). However, because Japan is substantially further from Thailand than ASEAN nations, the emissions released by each flight are higher. This results in flights to Japan being at the head of the league table for total annual emissions. Likewise, although the number of flights to these countries is substantially lower, the greater emissions per trip means that the long-haul destinations of Germany, Australia, and the UK come after Japan as Thailand’s most important sources of aviation-related CO2 emissions. However, around half of Thai flights are to countries that are not yet CORSIA participants (e.g., China, Vietnam and India) and so during phase 1, these will not count towards emissions quotas. Overall, Thai carriers are therefore expected to be responsible for approximately 2.8 MtCO2 of offsets over 2024-2026, which is forecast to carry a price tag of USD 364 million, or over THB 1 billion.

- Phase 2 (2027-2035): With the transition to the mandatory enforcement of CORSIA and thus the inclusion of almost all global destinations in emissions calculations, the cost of offsets will continue to rise. For Thailand, this will mean that carriers will become responsible for emissions released on trips to and from the major destinations of China, Vietnam and India, which together account for 36.8% of all Thailand’s international flights. In particular, flights to China will become a major source of additional costs for carriers since the country is by some margin the most popular destination for Thai airlines and as of 2019, flights to and from China generated over 2.3 MtCO2 of emissions, making the country also the largest single source of these. Costs related to CORSIA will therefore escalate significantly in phase 2, with these forecast to reach THB 1.3-3 billion annually. Moreover, for the last three years of phase 2 (2033-2035), the calculation of the required offsets will include a consideration of the change in each airline’s emissions, and this has the potential to push the CORSIA costs faced by Thai players to almost THB 9 billion.

Over the lifetime of CORSIA (2021-2035), Thai carriers will be required to offset around 40 MtCO2 in emissions at an expected cost of over THB 20 billion. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) thus sees Thai demand for offsets being among the strongest in Asia, likely coming after only China, South Korea, and Singapore18/. However, almost all of this will come from the major Thai carriers of Thai Airways, Thai AirAsia and Thai AirAsia X, which over 2021 and 2022 were responsible for 90% of emissions from Thailand’s international aviation industry. These three airlines will also face higher costs relating to monitoring, reporting and verification since these each generate more than 50,000 tonnes annually of emissions covered by the CORSIA scheme and so are disqualified from taking advantage of the ICAO’s simpler and cheaper MRV system.

Nevertheless, the impacts of CORSIA on the overall economy will be fairly limited. Air travel itself is not a major contributor to the economy, and prior to the Covid pandemic, this accounted for just 1% of GDP19/, though under the impact of severe global travel restrictions, this had slumped to 0.4% by 2022. Moreover, the direct impacts will largely be felt by airlines and related industries, such as manufacturers and distributors of aviation fuel, since these are the primary sources of aviation-related greenhouse gas emissions. The enforcement of CORSIA may affect consumers if airlines pass the costs of offsets directly on to travelers in the form of higher ticket prices, but even so, many consumers are willing to accept higher prices in exchange for reduced environmental impacts. This is reflected in a survey carried out by McKinsey in 2023 that showed that worldwide, 85% of travelers would accept a 2% premium on airfares to cover the cost of offsets20/. Similarly, a survey by Krungsri Research carried out in 2024 revealed that 93% of Thai consumers were prepared to pay more for environmentally friendly goods and services21/.

Carbon credit markets

The CORSIA will support a substantial expansion in demand for carbon credits, especially at the end of the pilot phase and the transition to phase 1 (2024-2026), a point that will coincide with the return of the global airline industry to normal conditions. Worldwide, demand for carbon credits from airlines is initially expected to come to approximately 150 MtCO222/. but across the duration of the scheme, this is forecast to grow by an order of magnitude to 1,500 MtCO2. Thailand’s share of this will amount to some 2.8 MtCO2 over 2024-2026, though this will triple to 9 MtCO2 through 2027-2029, when CORSIA enters the period of mandatory enforcement.

In particular, the market for high-quality carbon credits is likely to see solid growth since the ICAO has restricted the list of acceptable offsets to those accredited by only a small number of bodies. In the pilot phase, credits certified by eleven authorities are acceptable, but in phase 1, the choice narrows to only two, as of March 2024 (Figure 8). Nevertheless, offsets from other accrediting bodies (e.g., the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS), the Gold Standard (GS), and Thailand’s Premium T-VER23/) are conditionally accepted. For example, in the case of Premium T-VER, to account for lost offsets, adjustments to the accrediting process need to be made with regard to the management of buffer credits24/.

The stipulation that only a narrow range of high-quality carbon credits will be acceptable as CORSIA offsets has created challenges on the supply side of the market, and with only two permissible accrediting bodies, availability is a significant problem. Indeed, it was only in February 2024 that the first credits came to market that could be used for offsets required under phase 1 of the scheme. These come from a forestry project in Guyana that has been approved under the ART framework, but these sold at USD 20/tonne25/, far ahead of the USD 0.3-13/tonne26/ for other credits sold in the same month. In addition, the project will furnish just 7.14 MtCO2-worth of credits, or around 5% of forecast total demand under phase 1 of CORSIA. Given this substantial shortfall in supply, it remains to be seen whether the market will be able to adjust, and in the future, the ICAO may relax the current regulations to allow the use of offsets accredited by a wider range of bodies. It is therefore possible that to help broaden supply, credits that were acceptable during the pilot phase (including those from Premium T-VER) might in the future also be accepted under phase 1.

Nevertheless, the stringent requirements imposed by the ICAO mean that at present, the supply of suitable carbon credits remains very limited and so naturally, the market has placed a CORSIA premium on the few offsets that do qualify. These price differentials are reflected in the S&P Global Carbon Credit Index (Figure 9), which shows that the price for Platts CEC, i.e., CORSIA-eligible Credits or credits that are acceptable for use in CORSIA, trades above the price of almost all other types of carbon credits, and although the CORSIA-eligible credit prices trended down through 2023, as of the start of 2024, these rebounded at around USD 10-12/tonne. Moreover, prices for CORSIA-eligible offsets are likely to rally higher because in addition to demand from the airline industry, the signaling effect of acceptance under CORSIA will add to demand from non-airline businesses looking for best-in-class carbon credits27/.

Sustainable aviation fuels

Once CORSIA is fully implemented, sustainable aviation fuels (SAFs) will be a significant route to achieving reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. Relative to current jet fossil fuels, SAFs can cut emissions by 73-99%, though the exact savings will depend on the type of feedstock being used and the technology employed in its production28/. SAFs can be manufactured from a wide range of bio-inputs, including major crops, agricultural waste, animal fats, used cooking oil and refuse, or from green hydrogen or direct carbon captured from the atmosphere (Table 4).

In addition to providing airlines with a low-carbon fuel, SAFs also have the advantage of being ‘drop-in fuels’, that is, they can be ‘dropped-in’ in place of current fossil-based aviation fuels. Because these are very similar, SAFs can be mixed with jet fuels in a ratio of up to 1:1, and perhaps more importantly, their use does not require that airframes be redesigned or that fueling infrastructure be rebuilt. In addition, the SAF technological frontier is constantly being advanced. One interesting example of this is progress on the use of hydroprocessed esters and fatty acids (HEFAs) made from inputs such as used cooking oil, which has now been shown to be safe and viable as a transport fuel.

However, despite these clear benefits, transitioning to the wider use of SAFs will require overcoming a number of challenges. (i) At a 2022 average of USD 2,437/tonne, SAFs are currently around 2.5-times as expensive as standard jet fuel29/. Such a high price has significant consequences for carriers’ operating expenses since for Thai airlines, fuel accounts for 30-45% of all outgoings. (ii) Global production capacity remains limited, and although output rose 5-fold between 2020 and 2022 to reach 0.24 million tonnes, this accounts for just 0.1% of jet fuel production. (iii) Sourcing and securing sufficient feedstocks remains problematic as a result of demand for alternative uses and volatile prices, particularly for agricultural goods.

On balance, while it is true that the SAF market is only at the initial stages of development and its further expansion will require battling against a range of headwinds, strong demand from the global airline industry should underpin rapid growth. From the point of view of buyers, producing high-quality SAFs will help carriers reduce the need to make offsets under the CORSIA scheme, while different economic regions have also introduced policies that will help to further increase the production and consumption of SAFs by airlines operating both domestically and internationally. For example, the EU has introduced rules that require European airlines to use at least 2% SAFs in their aviation fuel by 2025, though this proportion rises with time to reach 70% by 205030/. Similarly, Japan has set a goal of SAFs accounting for 10% of aviation fuel by 2030, and the US is providing tax credits to producers of SAFs that are worth up to USD 1.75/gallon31/.

Within Thailand, businesses are paying greater attention to the SAF market, and companies are beginning to ramp up production. BSGF, a joint venture between Bangchak, Thanachok Oil Light and BBGI, aims to sink THB 10 billion into the production of SAF from used cooking oil, with commercial operations scheduled to begin in 202532/. In April 2024, Energy Absolute (EA) and Bangkok Aviation Fuel Services (BAFS) also announced that they planned to fund a joint venture to build an SAF blending facility and to manufacture SAFs from bio-inputs and other materials33/. Given its strengths in agriculture and food processing and thus its access to the raw materials needed to produce these fuels, Thailand is well placed to benefit from this newly emerging market.

Aircraft manufacturing

The enforcement of CORSIA and the wider move to make the industry much more sustainable has encouraged businesses to push forward with the development of new low-carbon aviation technologies. Examples of these include aircraft that are able to run on 100% SAF, hydrogen-powered planes, electric planes, and hybrid-electric aircraft that can achieve up to 40% emissions reductions relative to current fleets34/.

Of the various green technologies currently being discussed in aviation circles, the most promising route to net zero remains SAFs, and although at present, current technology limits the use of this to a maximum 50:50 mix with jet fuels, these restrictions are being steadily pushed back. The giant European manufacturer Airbus has been among those working on improving the efficiency of SAF-powered jet engines, and in 2023, the company successfully tested a passenger jet flying on 100% unblended SAF35/. Airbus now plans to make all its commercial models 100% SAF-compatible by 203036/.

The outlook for planes running on alternative fuels (e.g., hydrogen, 100% electric, or hybrid power) is less certain, and commercial development of these remains hampered by uncertainties over how rapid future progress will be. At present, electric- and hydrogen-powered flights are possible only over short distances or for limited passenger numbers37/, and in addition to its other problems, the use of hydrogen as a fuel suffers from difficulties sourcing the quantity of green hydrogen needed to expand services. Nevertheless, Airbus hopes to be the first major manufacturer to produce hydrogen-powered aircraft by 2035.

Aligning the airline industry with the net zero goals

For some time, airlines have recognized the importance of reducing their environmental impacts, particularly their carbon emissions, and of making their industry significantly more sustainable. Some notable examples of how companies have approached these challenges are described below.

Encouraging consumers to play their part in offsetting efforts

When booking a ticket, many airlines give travelers the choice of paying an additional fee to cover the cost of contributions to a voluntary carbon offsetting scheme. Singapore Airlines provides this option, and so for example, when booking an economy class ticket for the Bangkok-Singapore flight, travelers are able to pay an additional SGD 1.49 that will then be used to buy the high-quality carbon credits required to offset the estimated 114.6 kg in CO2 emissions generated by that flyer38/. Many airlines have implemented similar models, some examples of which include Cathay Pacific’s Fly Greener program, Turkish Airlines’ Co2mission scheme, and Japan Airlines’ JAL Carbon Offset system39/. Thai Airways used to operate a voluntary offsetting scheme that allowed travelers to purchase offsets targeting alternative energy when booking tickets through their website, but this was suspended in January 202340/.

Use of these schemes by international airlines will very likely expand in the future, particularly once CORSIA offsets switch from being voluntary to mandatory, and indeed, it is not only airlines that are providing access to aviation-related offsets; booking platforms such as Trip.com41/ and Traveloka42/ have also moved into this space and now offer a range of offsetting options for travelers. IATA is helping to support the development of this market by publishing its ‘Aviation Carbon Offsetting Guidelines for Voluntary Programs’43/ and by developing the Aviation Carbon Exchange (ACE), a platform that provides a centralized marketplace where airlines and other stakeholders may trade CORSIA eligible carbon credits44/.

Use of SAFs

Airlines worldwide are beginning to test SAFs and to set targets for their use in commercial operations. Japan Airlines began testing the use of a 1% SAF mix in 2021, while Emirates made the somewhat more ambitious leap to testing 100% SAF-powered flight at the start of 202345/. Closer to Thailand, AirAsia is the first carrier in the ASEAN zone to use SAFs on commercial flights, while Thai Airways plans to increase its use of sustainable fuels, bringing these to 2% of the airline’s total fuel consumption by 202546/. To this end, the company has signed a memorandum of understanding with PTT and Bangchak to promote greater use of SAFs, and at the end of 2023, the national carrier began a pilot program using these on its Phuket-Bangkok line47/.

Some airlines are also giving customers the option of paying a premium to support greater use of SAFs. Flyers on the German carrier Lufthansa thus have the choice of buying a more expensive ‘Green Fare’, with the additional fee being used to fund a 20% reduction in emissions through the use of SAFs and then to offset the remaining 80% of emissions with the purchase of high-value environmental carbon credits48/. Other airlines such as Finnair, Swiss and British Airways offer similar schemes combining offsets with additional fees for SAFs, while Air France has taken a slightly different approach and has raised ticket prices by EUR 1-8 to cover the additional cost of using sustainable fuels49/.

Exploiting efficiency gains to cut fuel consumption

In addition to changing the composition of their fuel, airlines are experimenting with altering airframes and operating techniques as a way of making efficiency gains that will then translate into reduced fuel consumption. The Irish airline Ryanair has therefore taken advantage of the development of drag-reducing split scimitar winglets, which it has retrofitted to its fleet, thereby cutting fuel use by 5% and slashing emissions by 165,000 tonnes annually. In a similar vein, Swiss has fitted AeroSHARK film to its aircraft and the resulting drop in in-flight surface friction across the aircraft body cuts emissions by 15,200 tonnes per year. A different track has been taken by Thai AirAsia, which has instead implemented its ‘green operating procedures’. These focus on reducing fuel use through changes to operating procedures, for example by making more efficient use of flaps when landing and by taxiing with only a single engine once on the runway50/.

Beyond switching to sustainable fuel and implementing the other changes to airframes and operations described above, airlines are also making a large number of smaller alterations to services as they try to reduce their emissions and cut their other environmental impacts. For example, Japan Airlines has moved to the use of electric vehicles for its in-airport ground services, Alaska Airlines has stopped using plastic glasses on all its flights and is switching to paper/card-based packaging instead, and both Bangkok Airways and Thai Airways have designed uniforms and products made from recycled inputs. Individually, the impacts of these moves may be limited, especially when compared to major changes such as the widespread uptake of SAFs and fuel efficiency gains, but these nevertheless reflect the desire of carriers to make progress towards their net zero goals wherever they can.

Krungsri Research view: Thai aviation taxiing towards sustainability takeoff

CORSIA is a global agreement aimed at harnessing the power of market mechanisms to decarbonize the aviation sector. From the national perspective, Thailand has had the good fortune to participate in the scheme since the 2021-2023 pilot stage and so the country has secured for itself a frontline position as the industry soars towards sustainability. Moreover, the Thai airline industry’s extended experience of navigating the CORSIA framework has given players the opportunity to explore, solve and overcome problems and obstacles prior to its full implementation, and with participation in the scheme ultimately unavoidable for all but a small number of countries, this advance experience may prove to be invaluable.

Clearly, as with much of the energy transition and indeed the majority of green policies overall, the enforcement of CORSIA will bring with it additional overheads. In particular, international carriers will have to deal with three new cost centers: measuring, reporting and verifying emissions (MRV); reducing emissions; and purchasing offsets when reductions cannot be made. However, enforcement of CORSIA is staggered and so while the additional overheads related to the first of these (i.e., MRV) is now a reality, costs connected to emissions cuts and carbon credits will ramp up in stages in the future, though these are nevertheless likely to become a significant concern for most businesses. For Thai operators, the short-term costs will remain slight and the implementation of phase 1 over 2024-2026 will have only limited consequences, partly because only around half of Thai international flights will qualify for inclusion in the CORSIA calculations. However, this situation will not last, and from 2027, the extension of CORSIA to include almost all international flights will potentially mean that carriers will need to make offsets for flights to and from all the country’s major tourist markets. In the last three years of the scheme (2033-2035), costs may again rise as a result of the switch to including a consideration of changes in an individual airline’s greenhouse gas emissions alongside the overall sectoral changes when calculating the level of required offsets. Thus, at this point, rather than being determined by large-scale shifts in the industry, an airline’s own progress towards sustainability will begin to have a bearing on the costs that it faces. Beyond this, CORSIA is subject to review every three years, with the next of these due in 2025, and so costs could also be influenced by changes to the CORSIA framework. These could include alterations to the baseline or to the means for calculating required offsets, or by the entry to the scheme of new participants.

Going forward, emissions from Thai aviation are very likely to rise given both the central place of tourism as a driver of the economy and the government’s stated aim of establishing the country as an aviation hub. It is therefore crucial that the government and stakeholders recognize the importance of CORSIA and begin working on reducing carbon emissions throughout the aviation ecosystem. These efforts will happen across the three core areas of MRV, emissions reductions, and offsets.

-

Development of MRV systems: These are required to fulfill the CORSIA MRV requirements, but although Thai airlines have been reporting emissions since 2022, four out of seven carriers use the ICAO’s ready-made CO2 Estimation and Reporting Tool (CERT). At present, they can do this because their emissions are below the 50,000 CO2 annual limit but if these grow beyond this cap, these companies will be required to develop their own MRV systems and to shoulder the costs associated with this. More generally, data from the Stock Exchange of Thailand (SET) show that Thai companies are broadly unprepared for MRV requirements, and as of the end of May 2024, fewer than half of all companies listed on the SET reported their emissions. Worse, fewer than a third of public companies were able to verify their overall carbon footprint51/. This is an area where companies need to perform better, and in response to both domestic factors (e.g., the draft climate change bill) and changes in international measures (e.g., the enforcement of the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) and the CORSIA framework, both of which require accounting for carbon emissions, though in different industries) much more focused efforts on the rollout of effective MRV systems need to be made.

-

Reducing emissions from aviation: Cuts in the quantity of greenhouse gases released by the aviation industry will be made through improvements in efficiency, the development of new technologies, and the switch to sustainable aviation fuel. The last of these will be especially important, partly because this will help carriers achieve the twin goals of cutting the costs of CORSIA enforcement and of greening their business operations. However, the domestic market for SAFs needs additional help to get established. On the demand side, the market would benefit from the setting of a minimum level of SAFs that should be mixed with standard aviation fuel52/ as well as from additional financial support. At the same time, to add to supply and boost Thai players’ growth potential, efforts should be made to promote greater investment across the length of the SAF supply chain, from sourcing inputs and collecting waste to converting this into useable fuel. Interventions such as these on both the demand and supply sides of the market have the potential to alleviate problems related to price and production capacity that currently restrain development of the industry, and through this, ensure a much more positive outcome for SAF producers and the aviation industry overall.

-

Improving the quality of offsets and ensuring that environmental projects are all high-quality: Efforts at improving the quality of carbon credits should focus on bringing these into line with the CORSIA requirements, particularly through the period when businesses are still struggling to bring down their own emissions. As airlines have done with more environmentally aware flyers, businesses might be able to take advantage of consumers’ willingness to participate in the offsetting process by paying an additional premium for this. However, taking this route requires that companies communicate effectively with consumers and convince them that any premium paid will indeed be directed entirely towards high-quality environmental projects. Government agencies that have responsibilities in this area also need to work on ensuring that companies have access to a sufficient quantity of high-quality carbon credits. Nevertheless, if the Premium T-VER verification system is recognized by CORSIA, this will help Thai carriers access the offsets required by the scheme, and moreover, this will provide a major opportunity for Thailand-based providers of carbon credits to meet growing domestic and international demand for these.

Ultimately, the financial sector will play a central role in helping companies in the aviation industry adapt to increasingly stringent environmental measures such as CORSIA. This might be through a number of different channels, such as providing the capital needed by airlines to develop their MRV systems, to cut their emissions and to purchase offsets for emissions when these cannot be reduced, or supplying investment funds for players in SAF supply chains or developers of projects qualifying for carbon credits. And while the airline industry might have a reputation as a particularly hard-to-abate corner of the economy, the financial sector may be able to provide a runway long enough for the industry to finally take off and carry the world to the heights of ‘fly net zero’.

References

Asian Development Bank (ADB). (2020). “Carbon Offsetting in International Aviation in Asia and the Pacific: Challenges and Opportunities”. Retrieved from https://www.adb.org/publications/carbon-offsetting-international-aviation-asia-pacific

Deloitte China. (2023). “Sustainable Aviation Fuels (SAF) in China Checking for Take-off”. Retrieved from https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/cn/Documents/energy-resources/deloitte-cn-saf-en-230922.pdf

International Air Transport Association (IATA). (2023). “Fact sheet CORSIA”. Retrieved from https://www.iata.org/en/iata-repository/pressroom/fact-sheets/fact-sheet---corsia/

International Air Transport Association (IATA). (2024). “IATA CORSIA Handbook”. Retrieved from https://www.iata.org/contentassets/fb745460050c48089597a3ef1b9fe7a8/corsia-handbook.pdf

International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO). (2024). “CORSIA Newsletter April 2024”. Retrieved from https://www.icao.int/environmental-protection/CORSIA/Documents/CORSIA_Newsletter_Apr%202024__ENV_1.pdf

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (2022). “Report on CORSIA implications and carbon market development”. Retrieved from https://www.undp.org/ukraine/publications/report-corsia-implications-and-carbon-market-development-deliverable-32

1/ https://ourworldindata.org/global-aviation-emissions

2/ International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO)

3/ https://www.iea.org/energy-system/transport/aviation

4/ https://www.caat.or.th/th/archives/81071

5/ https://www.icao.int/environmental-protection/CORSIA/Documents/CCR%20Info%20Data%20Transparency_PartI_11ed_web.pdf

6/ Carbon credits are an accounting mechanism used to represent reductions in or sequestrations of greenhouse gases relative to assumed emissions in a business-as-usual base case. These are generally calculated in tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (tCO2e) and to be valid, need to be confirmed by a recognized body (For more details, please see: https://www.krungsri.com/en/research/research-intelligence/carbon-credit-2023)

7/ https://www.icao.int/environmental-protection/CORSIA/Documents/CORSIA%20Eligible%20Emissions%20Units/CORSIA%20Eligible%20Emissions%20Units_March%202024.pdf

8/ https://www.icao.int/environmental-protection/CORSIA/Pages/CORSIA-Eligible-Fuels.aspx

9/ https://www.caat.or.th/th/archives/81068

10/ https://www.icao.int/environmental-protection/CORSIA/Pages/state-pairs.aspx

11/ The ICAO is expected to publish the 2023 SGF in October 2024.

12/ This aligns with the forecasts made by the ICAO and the IATA. The former sees the required offsets coming to 600-2,100 MtCO2, while the latter puts the figure at 1,100-1,800 MtCO2.

13/ https://www.icao.int/environmental-protection/CORSIA/Pages/CORSIA-FAQs.aspx

14/ Committee on Aviation Environmental Protection (CAEP), March 2022, https://www.icao.int/environmental-protection/CORSIA/Documents/2_CAEP_CORSIA%20Periodic%20Review%20%28C225%29_Focus%20on%20Costs.pdf

15/ As per the requirements for measuring and reporting CO2 emissions that came into effect on 12 February, 2022, holders of Air Operator Certificates (AOCs) operating aircraft need to collect and report annual data on flights and fuel consumption to the CAAT by 20 February of the following year. For more details, please see: https://dl.parliament.go.th/backoffice/viewer2300/web/previewer.php , https://www.bangkokbiznews.com/environment/1068409 , https://www.infoquest.co.th/2023/297863

16/ ICAO (Last updated: 21 December 2023), https://www.icao.int/environmental-protection/CORSIA/Documents/CORSIA_AO_to_State_Attributions_8ed_web.pdf

17/ Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR)

18/ https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/656086/carbon-offsetting-international-aviation-asia-pacific.pdf

19/ Air travel was the source of 3.3% of all Thailand’s travel-related carbon emissions in 2019. The industry is thus a more important source than water or rail travel, but is significantly less important than road transport, which generated more than 90% of travel-based emissions in the year.

20/ https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/aerospace-and-defense/our-insights/decarbonizing-aviation-executing-on-net-zero-goals

21/ For more details on ‘ESG Survey: Do Today’s Consumers Care About ESG?’, please see https://www.krungsri.com/en/research/research-intelligence/esg-survey-2024

22/ Similarly, the International Air Transport Association (IATA) sees demand for carbon credits for use as offsets coming to 64-162 MtCO2 during phase 1 of CORSIA https://www.cfp.energy/insight/navigating-the-aviation-industrys-transition-to-corsia-phase-1?utm_content=173716959&utm_medium=social&utm_source=linkedin&hss_channel=lcp-651816

23/ The Thailand Greenhouse Gas Management Organization (TGO) established the Premium T-VER scheme in 2022 to improve standards for Thai carbon offsets and to bring these into line with international norms. To qualify, projects must demonstrate that: reductions in greenhouse gas emissions are real and permanent, reductions are in excess of what would normally occur, there is no double counting of cuts, sustainable development is supported, safeguards are in place to prevent negative impacts, and the do-no-net harm principle is rigorously adhered to. For more details, please see: https://ghgreduction.tgo.or.th/th/t-ver/143-premium-t-ver/about-premium-t-ver.html

24/ The ICAO’s Technical Advisory Body (TAB) has proposed that the Thailand Greenhouse Gas Management Organization adjust its system for managing buffer credits to ensure that if credits are lost, these can be fully replaced. https://ghgreduction.tgo.or.th/th/ghg-news/ghg-news-events/item/4353-premium-t-ver-corsia.html (For projects targeting emissions reductions, sequestration and storage in agriculture and forestry, there is a risk that illegal logging, wildfires, and the spread of disease and insect infestations can negatively impact offsetting projects and so to counter this, buffer credits, or additional credits that are recorded but held in reserve, may be used to make good these losses) https://ghgreduction.tgo.or.th/th/rules/buffer-credit.html

25/ https://lcds.gov.gy/guyana-announces-worlds-first-carbon-credits-for-use-in-un-airline-compliance-programme-corsia/

26/ S&P Global’s Platts Carbon Credit Assessments, referenced in the TGO’s Carbon Monthly Newsletter (Feb 2024)

27/ https://www.southpole.com/blog/new-corsia-updates-will-impact-more-than-just-airlines

28/ https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Clean_Skies_Tomorrow_SAF_Analytics_2020.pdf and https://techsauce.co/sustainable-focus/sustainable-aviation-fuel-in-sea-thailand

29/ https://www.iata.org/en/iata-repository/publications/economic-reports/sustainable-aviation-fuel-output-increases-but-volumes-still-low/

30/ https://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/en/market-insights/latest-news/agriculture/010224-global-saf-production-set-to-double-in-2024-with-future-growth-policy-dependent

31/ https://www.iea.org/energy-system/transport/aviation

32/ https://www.bangchak.co.th/th/newsroom/bangchak-news/1271/กลุ่มบริษัทบางจาก-วางศิลาฤกษ์-หน่วยผลิตน้ำมันอากาศยานยั่งยืน-saf-แห่งแรกในไทย

33/ https://thaipublica.org/2024/04/ea-x-bafs-saf-co2-net-zero-pr-09042024/

34/ https://www.iata.org/en/iata-repository/pressroom/fact-sheets/fact-sheet-new-aircraft-technology/

35/ https://www.airbus.com/en/newsroom/stories/2023-03-airbus-most-popular-aircraft-takes-to-the-skies-with-100-sustainable

36/ https://arab-forum.acao.org.ma/uploads/presentation/Presentation_Airbus.pdf

37/ https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/aerospace-and-defense/our-insights/decarbonizing-aviation-executing-on-net-zero-goals

38/ https://carbonoffset.singaporeair.com.sg/

39/ https://www.businesstraveller.com/features/guide-to-airline-carbon-offset-programmes/

40/ https://www.thaiairways.com/th_TH/plan_my_trip/carbon_offset.page

41/ https://www.trip.com/trip-page/carbon-offsetting-your-flights.html?source=online&locale=en-gb

42/ https://www.traveloka.com/en-sg/promotion/go-green

43/ https://www.iata.org/contentassets/922ebc4cbcd24c4d9fd55933e7070947/aviation_carbon_offsetting_guidelines.pdf

44/ https://www.iata.org/en/programs/environment/ace

45/ https://www.greennetworkthailand.com/sustainability-in-aviation-industry/

46/ https://www.bangkokbiznews.com/business/economic/1088734

47/ One Report (2023)

48/ https://www.lufthansa.com/th/en/green-fare.solo_continue?&utm_source=bing&utm_medium=cpc&utm_campaign=TH_EN%20-%208_DSA&utm_term=lufthansa.com%2Fth%2Fen&utm_content=TH_EN%20-%20DSA&gclid=CNHB-N3AtIYDFcVLwgUd64sREw&gclclass="img-fluid" src=ds

49/ https://www.businesstraveller.com/business-travel/2023/01/16/air-france-increases-ticket-prices-to-pay-for-sustainable-aviation-fuel/

50/ https://www.bangkokbiznews.com/business/business/1021981

51/ https://www.sdthailand.com/2024/06/set-drive-pilot-project-carbon-calulator-platform/

52/ As per the Oil Plan 2023 and the AEDP 2023, Thai authorities are expected to mandatethat by 2027, at least 1% of fuel used by the airline industry should be from SAFs https://www.thairath.co.th/money/sustainability/esg_strategy/2701696