In the period 2019-2021, road freight operations should see annual growth of 1-2%. The industry will benefit from an anticipated expansion of industrial output, as well as from strengthening private and public sector investment together with improving agricultural yields. These factors will then feed into greater demand for the transport and distribution of goods domestically. In addition, operators will also benefit from the steady growth of cross-border trade and the rising popularity of online shopping.

However, at the same time, competition on price will tend to intensify due to the steadily increasing number of players active in the industry. Large operators and new overseas entrants to the market will likely increase their investments in their distribution fleet and will continue to expand their networks of commercial partnerships, while at the same time, official regulations governing the operations of hauliers will tend to become stricter and more onerous, and these factors will weigh on players’ income and profitability.

Overview

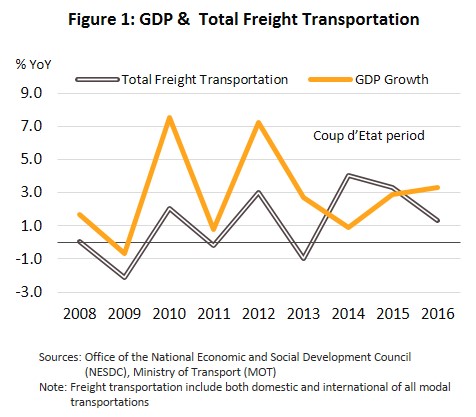

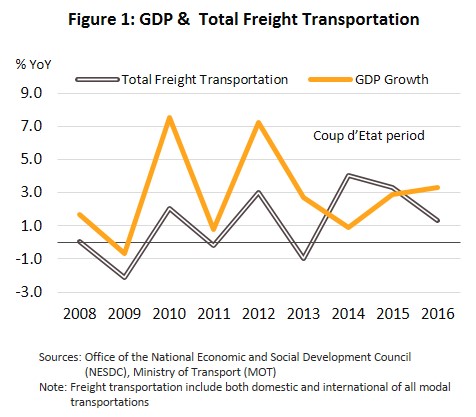

Both domestically and internationally, the transport sector plays a crucial role in distributing goods to markets, and providers of transportation services are responsible for moving goods at all stages of the supply chain, from upstream raw materials to midstream processes, through the downstream distribution of finished products. The business activities of the sector thus rises and falls in line with the quantity of goods being shipped, and this in turn is dependent on the economic situation (Figure 1).

Within Thailand, commercial transportation may be divided into five principal modes. (i) Road transportation naturally involves the use of different types of trucks or lorries, including pickups, container trucks, and refrigerated trucks. (ii) Rail transportation uses the country’s extensive rail network and offers a range of different options, including the transport of bulk, containerized and liquid goods. Within Thailand, there is a single rail service provider, the State Railway of Thailand. (iii) Distribution through pipelines is used with liquid goods, such as water, oil, natural gas and some chemicals. (iv) Water-based distribution is typically used for heavier goods and for inland transport, this will usually be products such as cereals and bulk building materials. As regards shoreline distribution, to support import-export activities, barges and feeder/cargo ships are used to transfer goods from smaller wharfs to the major, deep-water ports. (v) Air transport is typically used for high-value items, items requiring special care, smaller and lighter goods, and goods for which delivery is time-sensitive or which spoil quickly. Examples of these include electronics parts and equipment, jewelry, flowers, and orchids.

In terms of the five transport modalities described above,

road transport accounts for 81% (Figure 2) of all goods transported within Thailand (data as of 2016). This dominance of the sector stems from the fact that successive Thai governments have pursued a policy of prioritizing the use of the road system over the development of the infrastructure required for alternative transport networks, and this has had the result that at present. In terms of the total distance covered within the country by the different modalities, roads represent 86.9% of the total (Table 1). In addition to this, transportation by road also offers the advantage of door-to-door transport[1], so that senders may move goods from source or origin to recipient in a single mode and the ease and completeness of these connections between sender and recipient cannot be matched by any other alternatives. So, for example, in the case of distribution by rail, water or air, the use of some kind of ‘feeder’ road transport is still required to connect to the recipient on the final leg of the journey. For these reasons,

distribution of goods by road has the major role to play in the overall national goods distribution network, and this is reflected in the fact that overall expenditure on road transport is consistently greater than equivalent expenditure on other means of transport (Figure 3).

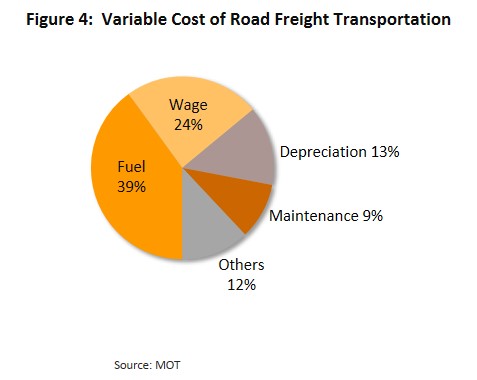

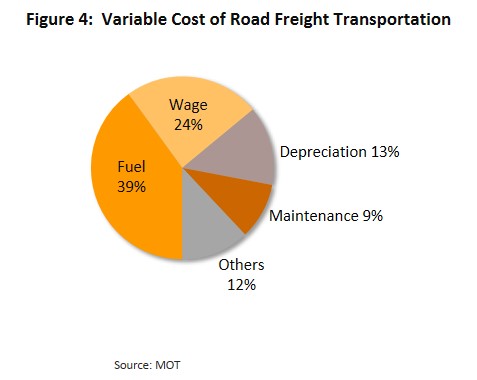

In addition to its advantages in terms of speed and convenience, road transport also benefits from the fact that distributing goods in a single stage without the need to make transfers, as is required when sending goods by other means, helps to reduce the risks that would otherwise arise from loss or damage caused when transferring cargo between vehicles. However, with the exception of air transport, moving goods by road is typically more expensive than the alternatives due to the relatively high share that variable costs contribute to overall business expenses. The most important variable costs are: (i) fuel, which accounts for an average of 39%of all variable costs (Figure 4); and (ii) labor, which represents a further 24% share of variable costs, with the cost of hiring drivers being particularly important; in the recent past, labor costs have risen steadily as a consequence of a supply shortages. In light of this and as a way of reducing costs and improving the efficiency of the distribution of domestic goods, Thai officials have made long-term plans to develop alternatives, and these focus in particular on increasing the proportion of rail and water-based transport.

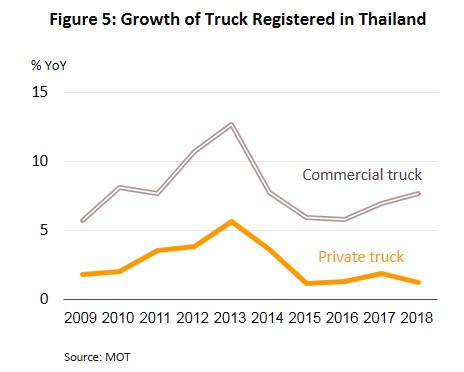

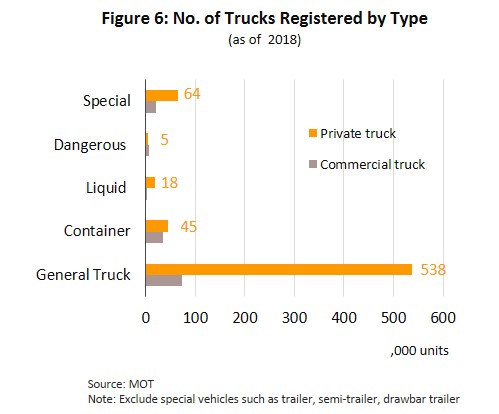

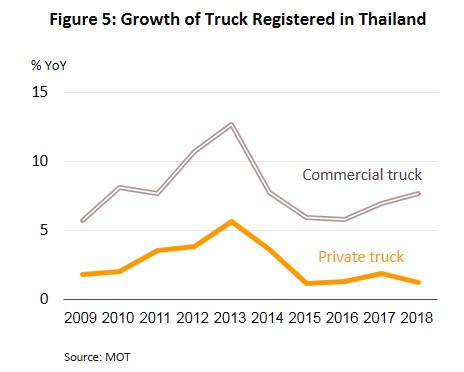

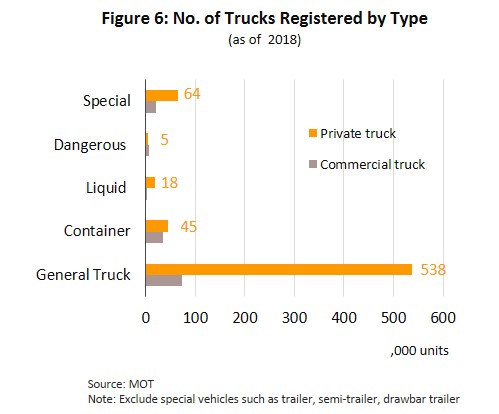

There are two main categories of vehicles used in the commercial transport of goods by road. These are (i) privately owned trucks, which are used for the transport of the owner’s own goods, and (ii) trucks operated by general haulage companies that are not operating on fixed schedules (source: Department of Land Transport). As of the end of 2018, a total of approximately 1,120,000 trucks were registered in Thailand and of these, 810,000 were privately owned (i.e. 72% of the total), with the total number of trucks operated by haulage companies coming to a further 310,000 vehicles (28% of the total). Thai manufactures thus tend to rely on in-house transportation facilities when distributing goods domestically and this is because of the certainty which they have that their goods will be delivered, and also because operating in this fashion reduces the risk of being affected by a sudden inability to access transport facilities. Despite this, though, over the three years from 2016 to 2018, the number of trucks registered with hauliers grew by 6.8% per year, compared to just 1.5% annual growth for trucks registered with other types of companies (Figure 5). This then signifies a move by businesses and manufacturers to gradually switch to outsourcing these services, a move that helps companies to: (i) cut business costs, including overheads related to administration and other costs arising from vehicle repairs, insurance, and personable costs (i.e. drivers); (ii) take advantage of the specialist expertise and experience of commercial haulage operators; and (iii) reduce the overheads involved in navigating the numerous official regulations governing the transport of goods. These include rules on the permissible weight of transported goods and of trucks, the maximum size of trucks and of their loads, and the permitted speeds and travel times of goods vehicles (which may vary depending on whether the vehicle is in urban municipal area or elsewhere)[2].

Type of goods transport by road

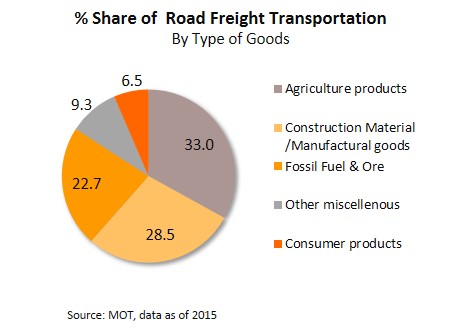

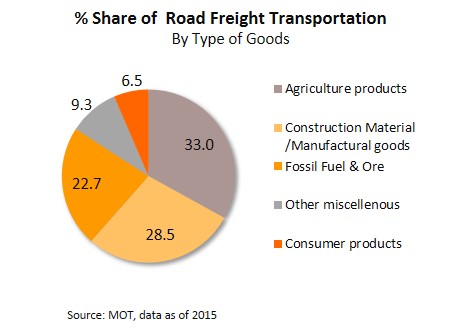

- Agricultural goods (live animals, crops, etc.) These represent 33.0% of all goods transported but the quantity on the road at any one time will tend to fluctuate substantially according to the time of year and the yields typically coming to the market at that period.

- Construction materials and industrial goods, such as equipment and machinery, cement, construction steel, gravel, earth and sand. This category accounts for 28.5% of the total, though again, this depends on the level and type of activity in the construction sector and this will vary according to the location. Thus, in industrial zones, transported goods will tend to be industrial raw materials and finished goods for export, while in urban areas, to meet growth in demand in the real estate sector, these will typically be replaced by large quantities of building materials.

- Fossil fuels (coal, etc.) These are a further 22.7% of goods transported, although fuels are usually moved over only fairly short distances from production centers to factories or plants for use or for further processing. Most of this is carried out by in-house transportation facilities or by companies contracted for regular distribution over fixed routes.

- Consumer goods and miscellaneous items. These occupy a fairly small share of the market, at just 6.5% of the total. This category includes finished goods being distributed to markets around the country and this may be done by in-house distributors (including transportation provided by companies within the same commercial network as suppliers) or by commercial haulers contracted to move goods on fixed routes between distribution centers and retail outlets.

- Other goods. The remaining 9.3% is composed of items such as dangerous goods, goods packed in containers, industrial waste, etc. These goods will typically be transported in specialized vehicles and operators will take deep caution and expertise in their transport.

The prices charged for transporting goods will usually be calculated according to their weight and the distance. Goods in categories 1-3 above are heavy bulk goods and so costs may be calculated on a per-vehicle basis, whereas goods in categories 4-5 may be transported on a per-vehicle basis (i.e. the vehicle will be loaded exclusively with a single customer’s goods), loaded with goods from a number of different customers, or distributed according to the good’s special handling requirements (such as is the case for dangerous goods or frozen goods, which require the use of particular types of vehicles). In the latter case, this will normally incur higher fees, partly due to the additional costs involved, such as for specialist insurance.

Haulage services may be classified into a number of different groups[3] and business conditions for operators offering each of these services may vary considerably, depending on the demand for the transport of particular goods, the number of vehicles that the business operates, the number of other operators offering services in each segment, the types of vehicles operated and the goods transported. Details are given below.

- Container trucks: These come in two types: (i) Chilled and frozen containers for the distribution of certain types of agricultural goods, and income for owners of these vehicles thus tends to be seasonal. (ii) General purpose containers for the distribution of industrial goods. Income for these operators is highly dependent on the level of output of goods for export. Companies may attempt to reduce business risks by agreeing long-term contracts for the provision of transport services, and they may also attempt to raise efficiency by ensuring that vehicles carry loads on both legs of their journey and by expanding business operations beyond traditional activities, which emphasize the transport of large items, to include distribution for online retailers, which places a greater focus on smaller, more numerous goods being dispatched and received more rapidly.

- Commercial vehicles for the transport of liquid goods, dangerous goods, and goods that have special handling requirements: Operators in this segment typically have specialist knowledge, particularly those that are involved in the transport of fuels and other dangerous goods[4] and so the market is relatively stable, with long-term contracts for the provision of transport services often being agreed. Income for players is thus secure, and they have some power when setting market rates, although turnover still fluctuates according to the state of the market for the goods being transported.

- General truck: This group faces significant competitive pressures due to the large and growing number of players active in the market. In 2018, a total of some 610,000 general purpose trucks were registered, or 75.7% of the total number of all trucks (excluding articulated and towed vehicles). Of these, 538,000, or 88% of all trucks, were privately operated (Figure 6) and this represents a significant obstacle for smaller hauliers, who have large numbers of unused vehicles sitting idle and for whom 45% of journeys are made by trucks carrying no cargo[5].

In addition to offering distribution services to meet demand from the domestic market as described above, operators have also had the opportunity to develop their businesses by distributing goods produced by Thai manufacturers to markets in neighboring countries. Several factors have helped to develop this market, including: (i) The opening of the ASEAN free trade area and the participation of countries in local cooperative efforts, including the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS), the Indonesian-Malaysian-Thai Growth Triangle (IMT-GT), and the partial merging of regional economies in the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC); (ii) Thailand’s natural advantages in terms of its geographical location and its shared borders with a large number of Southeast Asian nations, including Laos PDR, Myanmar, Cambodia and Malaysia, combined with its ability to engage in trade by land with a further five countries, namely Vietnam, India, Bangladesh, China and Singapore; and (iii) progress on the development of transportation infrastructure linking Thailand to its neighbors. This includes numerous roads, such as the nine Asian Highways, the twenty-three ASEAN Highways, the three Greater Mekong Subregion Highways and the two highways linking Thailand and Malaysia, the seventeen border crossings and the border bridges (Thai-Laos Friendship Bridge, the Thai-Myanmar bridge and the Thai-Cambodia bridge[6]).

Situation

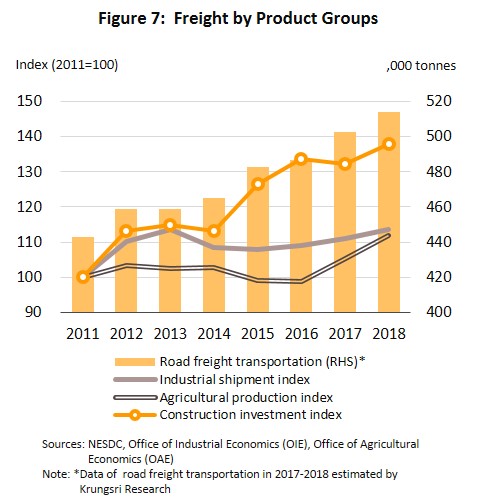

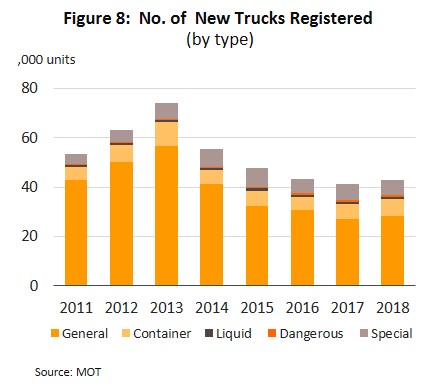

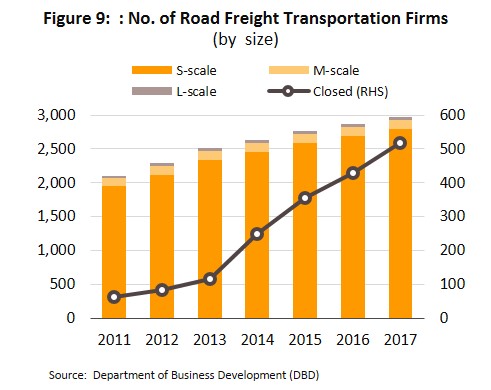

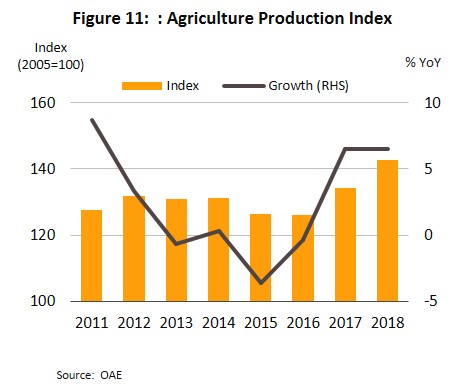

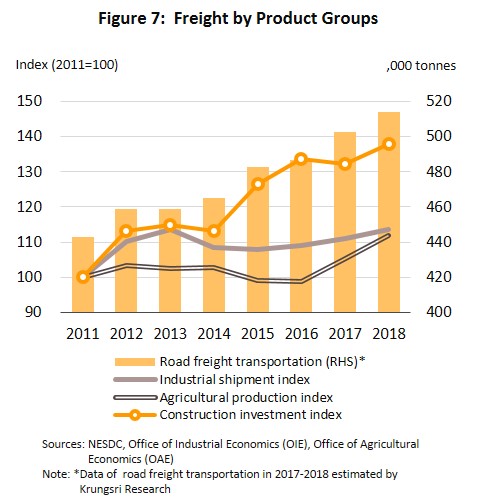

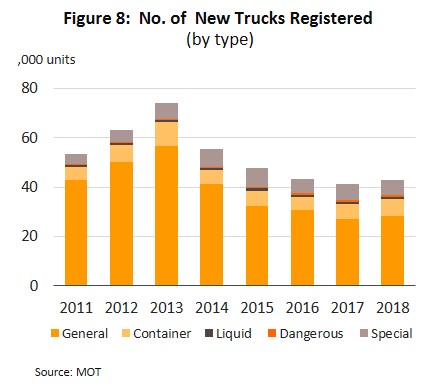

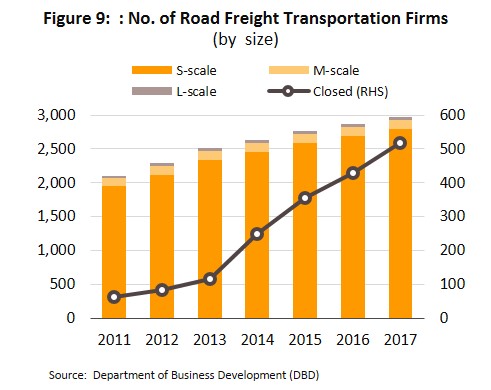

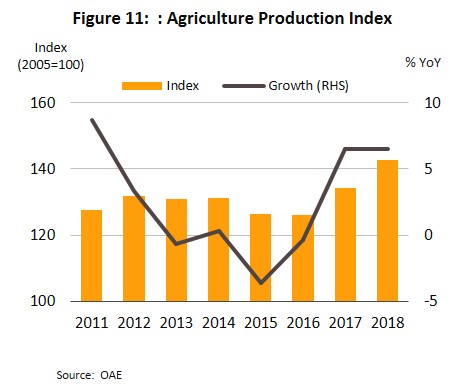

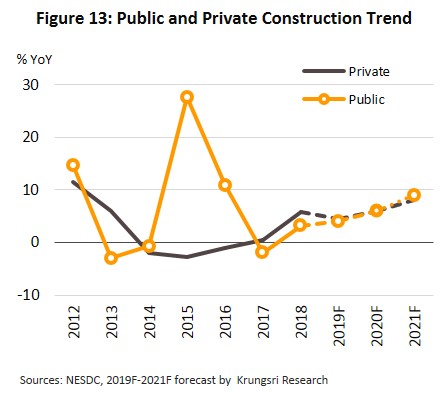

Between 2011 and 2016, business conditions in the road haulage sector steadily improved on average growth in the quantity of goods shipped of 2.4% per year (Figure 7). At the same time, the number of trucks registered contracted slightly, shrinking by an annual average of 0.04%. (This is with the exception of 2012-2013, when the numbers increased by an average of 0.2% to meet greater demand; following the widespread flooding of 2011, the volume of goods being transported nationwide rose to meet the considerably greater volume of household repairs). During this period, competition also stiffened, with the result that increasing numbers of small- and medium-sized hauliers were forced to cease operations (Figures 8 and 9), while growth tended to cluster in particular market segments, these often being the target of government stimulus packages. Thus, the transport of construction materials grew following expansion in government investment in large building projects. On the other hand, the transport of industrial goods by road saw only relatively low average rates of growth, having been hit by the effects of sluggish exports and weaker domestic consumer spending power, while the transport of agricultural produce was affected by sharp climate change[7] and the resulting farm losses and declines in yields. However, in 2017, signs of improving conditions became evident and the volume of goods transported by road increased on improving domestic demand, with the figures for both industrial and agricultural products rising. Thus, the indices of industrial freight and agricultural production increased by, respectively, 1.8% and 6.5% in 2017, compared to 1.3% and -0.4% in 2016. However, a weakening construction sector (the index of construction investment slid by -0.9%) led to a fall in the volume of building materials transported by road.

In 2018, business picked up substantially in all product areas for road hauliers on strengthening exports and rising levels of consumption domestically. As such, the industrial shipment index rose by 3.2%, while the quantity of agricultural goods transported increased strongly on more favorable climatic conditions and the higher yields of, for example, rice and maize, that resulted from this. In addition, the quantity of construction materials moved by road also benefitted from government spending on the build-out of infrastructure, the extensive construction work being carried out in the Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC) and private-sector investment in real estate developments, and the net effect of all of this was reflected in the 4.3% increase in the index of investment in construction. Beyond this, cross-border trade rose by 5.6% YoY (though this was down from the 9.8% YoY growth recorded in 2017) and overall, improving business conditions in 2018 prompted operators to expand the national truck fleet by more than 40,000 new vehicles.

Thai hauliers are overwhelmingly small-sized operations (small companies comprise a full 94.4% of all registered hauliers in Thailand) and they therefore have access to a limited customer base and find it is difficult to invest in technology and human resources. As such, those players that have only restricted working capital may encounter problems with maintaining solvency and so there is a steady stream of businesses exiting the market. By contrast, mid- and large-sized players are typically much more competitive and occupy a more favorable negotiating position within the market. This latter group may be subdivided into two further types. (i) Thai operators include companies offering comprehensive haulage services and international logistics service providers, with the latter including the logistics arms of large manufacturers and distributors. Within this group, notable operators include LEO Global Logistics, Kiattana Transport, Nim Si Seng 1988 Transport, Tiger Distribution and Logistics (part of the Sahapat Group), SCG Yamato Express (part of Siam Cement), JWD Transport (Thailand) (part of the JWD Infologistics group), and Sun Express (Thailand) (part of WICE Logistics). (ii) International operators active in Thailand[8] come from Germany, the United States, Japan, Australia, Singapore, and China. These players typically offer a wide range of logistics services (transporting via land, water and air), include integrated logistics service providers, have access to a large capital base, are part of extensive commercial networks, provide comprehensive services, and operate with the most up-to-date services and technology. Important players within this group include DHL, FedEx, NYK, CEVA Logistics, Linfox, K Line (Thailand) and Kerry Logistics.

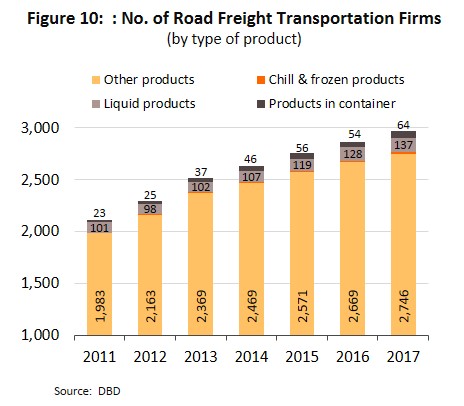

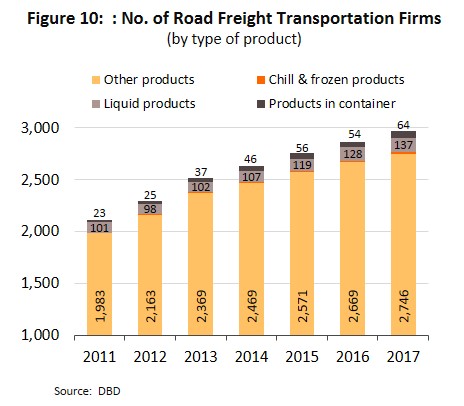

Details (as of 2017) of the business conditions for different segments of the road freight sector are given below[9] (Figure 10).

- Chilled and frozen haulage services: Twenty players are active in this segment, all of which are small-sized operations. The majority of goods that are transported are perishable, such as vegetables, fruit, dairy products, and seafood products, which moved from production or processing sites to consumer markets, while transporting agricultural produce that is at the stage of being an input into food-processing typically relies on producers’ own transport. In 2018, this segment benefited from rising agricultural yields (Figure 11), both of crops and livestock.

- Container haulage services: There are 64 registered players in this segment and 97% are small-sized. Industrial goods form the bulk of the items that are shipped in containers. In the past, income within the segment has risen in step with increases in the volume of goods produced, cross-border trade and improvements to infrastructure in both Thailand and in neighboring countries. In 2018, demand for the transport by land of containerized goods weakened somewhat for some product categories, for example for electronics and electrical goods, which suffered under the impact of the US-China trade war; exports of electronics and electrical appliances to the United States fell by -6.4% and -24.3% respectively, while exports to China of integrated circuits and of electrical appliances and other components slipped by -14.9% and -3.9%. However, at the same time, this segment also benefited from greater demand for the transport and distribution of goods domestically and in neighboring countries as a result of strengthening economic conditions.

- Oil and gas tankers: High barriers to entry into this market help to reduce competitive pressures for the 137 operators in this segment (86% of which are small-sized), while in the past, income has tended to rise in line with that of players in the oil sector (oil refineries, oil traders and petrol stations). In 2018, business was supported by a 1.7% YoY increase in domestic demand for finished petroleum products and a 26.7% YoY jump in exports of finished oil products (source: Department of Energy Business).

- Providers of other haulage services: There are a total of 2,746 providers of general haulage services and, again, almost all of these (95%) are small operations. This segment of the market is marked by its very low barriers to entry and so over the past three years, an average of some 90-100 companies have entered the market every year (source: Department of Business Development) and this has naturally led to strong levels of competition. In 2018, income for businesses was supported by the expansion of the Thai economy and higher levels of cross-border trade, in addition to the ever-rising popularity of online shopping, which has helped in turn to fuel demand for express deliveries and for the delivery of smaller parcels[10].

Industry Outlook

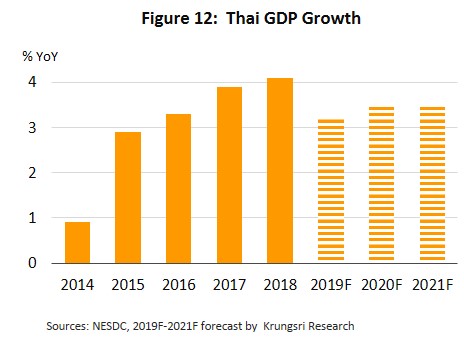

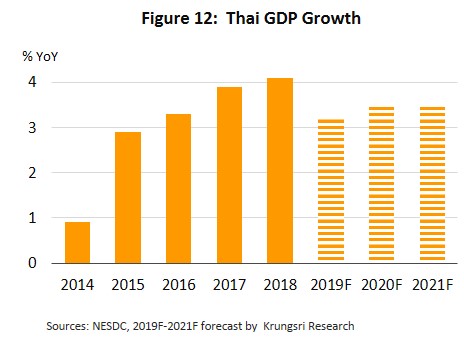

Following growth of 2.3% in 2018, through the period 2019 to 2021, it is expected that road freight businesses will see growth of 1-2% per year on rising demand for transport services that will move in line with growth in the economy more generally (Krungsri Research forecasts annual GDP growth of 3-3.5% in 2019-2021) (Figure 12). Factors supporting increased demand for different market segments are given below.

- Agricultural yields will tend to increase, especially for products that command better prices, such as rice, maize, fruits, broiler and fishery products, and this will prompt farmers to increase the area of these crops under cultivation, while processed goods such as chicken meat, seafood, and chilled and frozen fruits will benefit from rising demand on both domestic and export markets. This will then raise demand for the services provided by operators who are focused on the transport of agricultural goods and products connected to the food processing sector.

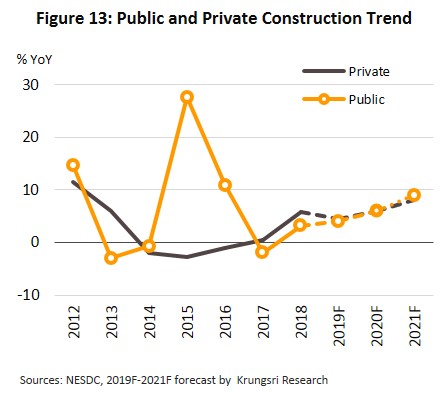

- Overall investment in construction will tend to rise steadily due to the government’s plans for developing large-scale national infrastructure[11]. Krungsri Research thus estimates that government-backed construction will expand by 3-5% in 2019, 5-7% in 2020 and 8-10% in 2021 (Figure 13) and that this will help to pull in private sector investment with it through the crowding-in effect, with funds going to industrial, commercial and residential real estate developments. This will then lifts private sector investment in construction by 4-5% in 2019, before the market picks up and grows by 5-7% in 2020 and then by 7-9% in 2021. These factors will then naturally increase demand for the supply of transportation services, particularly of the large vehicles required for moving building materials.

- Industrial output may be dampened, caused by export slowdown in line with global trade. However, industrial output tends to rise with the positive factors are given below.

- Domestic consumption will grow steadily and this will boost demand for the transportation and distribution of consumer goods to markets within Thailand.

- Growth in cross-border trade and trade in the wider ASEAN region will be underwritten by the continuing economic strength of neighboring countries (the IMF forecasts that growth in CLMV countries will be in the range of 6-7% in 2019-2021) and this will then help to support greater demand for road transport services to distribute goods from ports, airports and border crossings across those borders and into the region[12]. The beneficiaries of this will thus be operators of containerized transport and pick-ups.

- The government’s investment support policies, especially with regard to the Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC), special economic zones and industrial estates, will also help to support demand for large capacity road transport.

- Continuing expansion in e-commerce and online shopping[13], especially in the business to consumer (B2C) segment (for which Thailand is the fastest growing market in the ASEAN region), and the popularity of home shopping will help to build additional demand for delivery services organized using smaller distribution vehicles.

In terms of the supply of haulage vehicles in the period 2019-2021, this will tend steadily to increase and it is forecast that new truck registrations will rise by an average of around 45,000 vehicles per year, or by 2.5-3.0% annually (down somewhat on 2018’s increase of 3.6%) in order to meet greater demand and to increase the coverage provided by operators, though in addition some portion of this will also be to replace aging vehicles within the road freight fleet. Large players will also tend to enter the market in greater numbers, especially foreign operators, which are expanding their markets in Thailand and in neighboring countries, and some of these may enter into partnerships with Thai SME hauliers, the latter subcontracting for the former. However,

operators will also have to face a number of challenges over the next few years arising from stricter regulations and with this, potentially higher operating costs. These will include new regulations on maximum permitted loads, the requirement to install global positioning systems to trucks that help tracking their movements, restrictions on the hours drivers may operate (part of moves to increase road safety)[14] and likely increases in labor costs following a rise in the minimum wage.

The combined effect of these will tend to restrict operators’ profitability, although given the fact that most Thai hauliers are SMEs, have limited access to financing, operate only in a restricted area, and lack extensive access to management systems and technology, the difficulties that they will face in competing with foreign players may also lead to a decline in the market share held by Thai transport companies.

Krungsri Research view

It is forecast that through the period 2019-2021, road hauliers will see steady but relatively slow growth on rising demand for transport services in all segments of the market. However, stiffening competition and rising costs (for labor and fuel) will tend to hold down turnover, especially for smaller operators or those that are not part of wider commercial networks.

- Providers of chilled and frozen transport services: For these players, growth should be at rates similar to those recorded in 2018. Although higher crop yields will increase demand for the transport of agricultural goods, labor and fuel costs will likely rise and this will put downward pressure on profit rates.

- Providers of petroleum, gas and liquids transport services: Income will grow strongly on higher domestic demand for petrol and gas in both the transport and household markets. Within this segment, competition is not particularly strong and so operators will be able to remain in profit.

- Providers of containerized transportation services: Within this segment, income may soften, although operators will have the opportunity to generate profits from growth in cross-border trade with neighboring countries, a market that is seeing solid growth. At the same time, government policy is supporting the transport sector and helping to speed up investment in related industries, such as by making cross-shipping in Laem Chabang port easier and more convenient and by opening distribution centers in special economic zones. However, the impact of countries raising barriers to trade and the slowing of the economies of major trade partners may lead to a reduction in exports and this would then cut demand for containerized transport services.

- General transport services: For large operators and/or those that are part of extensive commercial networks, the outlook is positive and these companies should see growth in the coming period due to the fact that they can rely on relatively stable demand. In addition, they may be able to increase income through investments in related businesses, such as by offering consulting services, contracting for the management of distribution networks, and by running packaging businesses. As for SMEs and independent operators, the crowding of the market and greater competition from foreign players will likely lead to a worsening of business conditions and to greater difficulties in managing businesses and in expanding income streams. As such, these smaller operators may need to build competitiveness by entering into business alliances with other players.

[1] Door to door transport refers to transport that uses a single means to move goods from source to destination without the transfer of the goods or the use of any other transport modalities (i.e. without trans-shipping).

[2] The Land Traffic Act specifies speed limits for trucks that have a combined weight of vehicle and load of over 1,200 kilograms. The maximum speed limits are 60 kph in Bangkok, Pattaya and in municipalities, and 80 kph elsewhere. For other types of goods vehicles, such as articulated lorries, that have a combined truck and load weight of over 1,200 kilograms, the speed limit is 45 kph in Bangkok, Pattaya and in municipalities, and 60 kph elsewhere.

[3] The issuing of permits to operate as a haulier and the registering of commercial transport vehicles is under the purview of the Department of Land Transport (DLT), which operates within the Ministry of Transport. The Department of Land Transport organizes and regulates the operations of these vehicles in line with the Land Traffic Act.

[4] The laws on transporting dangerous goods, e.g. the Hazard Substances Act, specify that the transport of fuels is overseen by the Department of Energy Business, the transport of radioactive materials by the Office of Atoms for Peace, and the transport of explosives by the Ministry of the Interior and the Ministry of Defence.

[5] Data on the proportion of trucks travelling with no load (the empty run rate) is from the Land rucking Federation of Thailand, 2018.

[6] The Thai-Cambodia Friendship Bridge connects Ban Nong Ian in Sa Kaeo Province, Thailand with Stung Bot, Banteay Meanchey Province, Cambodia. At present, construction work is underway and this is forecast to be completed in 2022.

[7] The strong 2011 La Niña precipitated flooding over a large area of agricultural land, while the particularly harsh El Niño in 2015-2016 triggered a severe drought and so insufficient water was available in reservoirs to support the full range of normal agricultural activities.

[8] Thanks to an agreement liberalizing the logistics sector within the ASEAN zone, Thailand now allows foreign operators to invest in/participate in joint-ventures with Thai players up to a value of 49% of a company’s registered capital. This is with the exception of international road freight operations, for which foreign players may own shares up to a value of 70% of registered capital.

[9] Compiled from data supplied by the Ministry of Commerce.

[10] The market for delivering parcels to addressees within 1-2 days has a current value of at least THB 30 bn (source: Thai Rath, February 8, 2019).

[11] This includes: the MRT Pink, Orange and Yellow lines, expansions to the Bangkok metro system, the high-speed rail link connecting Bangkok’s three airports (Suvarnabhumi, Don Muang and U-Taphao), inter-city motorways, expansions to national highways, the next phase of the twin-track railway system, phase 3 of the Laem Chabang Port upgrade, and work on the Batong and Sakon Nakhon airports. In addition, extensive work will be undertaken upgrading and expanding the road networks under the management of the Department of Highways and the Department of Rural Roads.

[12] Cross-border transport opens possibilities for trucks to travel and to stop on road networks in Thailand, Laos PDR, Myanmar, Cambodia, southern China and Vietnam.

[13] The Thai e-Commerce Association forecasts that the value of the domestic e-commerce market will increase ten-fold from its current level of 1–2% of the entire Thai retail market, while Euromonitor International estimates that the value of home shopping will rise from the 2018 figure of THB 12 bn to THB 16 bn in 2023.

[14] The Department of Land Transport announced that large trucks, those with ten or more wheels, and articulated vehicles were required to have a GPS system installed from January 25, 2016. Older vehicles (those registered before 2016) are required to be fitted with a GPS system by the end of the 2019 tax year, while those that have GPS systems that are not recognized by the Department of Land Transport have until 2020 to comply with the new regulations. As regards driving hours, drivers are not permitted to drive for more than 4 hours continuously in any 24 hour period. Should a driver rest for at least 30 minutes, s/he is then permitted to drive for another period of no longer than 4 hours.

.webp.aspx)