The chemical fertilizers industry will see only gradual growth over 2020-2022. Demand is expected to rise by an average of 1-2% per year driven by an anticipated increase in cultivation area for major cash crops (e.g. rice, maize for animal feed, and cassava) which together account for 60% of total domestic demand for fertilizers. However, operators’ profits will be pressured by several factors, including a volatile climate, rising input costs in line with higher prices of fertilizers in world markets, and additional overheads arising from the need to hedge against currency fluctuation.

In the coming period, manufacturers of chemical fertilizers will try to increase their income and place their businesses on a firmer footing by opening new distribution channels and offering more value-added products. For example, they would offer customized fertilizer compounds and increase exports to neighboring countries. However, the will also have to face challenges arising from greater consumer interest in organic farming and the increasing use of bio-fertilizers.

Overview

Chemical fertilizers are manufactured by synthesizing several chemicals from plant nutrients, the most important being nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P) and potassium (K). There are three major categories of chemical fertilizers:

1) Straight fertilizer contains only a single plant nutrient, although this is synthesized into a compound that will contain other elements. For example, of the three elements needed in large quantities by plants, ammonium sulfate fertilizer contains only nitrogen and is designated as 46-0-0 fertilizer, triple superphosphate (0-46-0) is composed of only phosphate, and potassium chloride (0-0-60) contains only potassium. The numbers refer to the percentage of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium content in the fertilizer.

2) Mixed fertilizer contains, as its name suggests, a mix of two or three of the main plant nutrients. For example, a commonly used fertilizer is 15-15-15, which contains equal portions of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium which provides all the main plant nutrients.

3) Compound fertilizer contain at least two of the three major plant nutrient elements which have been combined in a chemical process into a single compound. It contains the chemicals in a more regular or stable form than mixed fertilizers. Common examples of this class of fertilizer include potassium nitrate (KNO3), diammonium phosphate (NH4)2HPO4, and potassium metaphosphate (KPO3).

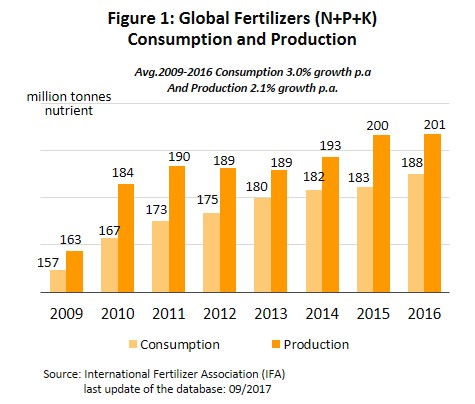

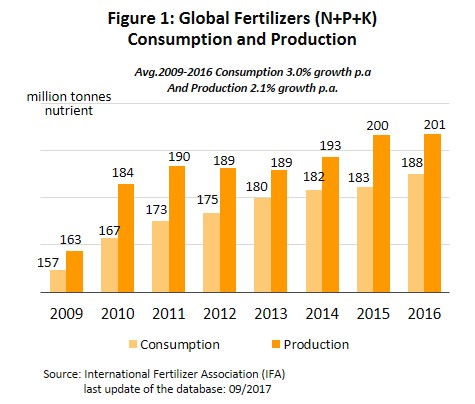

Demand for and supply of fertilizer is rising worldwide. This is partly supported by trends that are encouraging greater consumption of food crops, and the growing use of biofuel as an alternative source of energy. These are feeding the steady expansion of cultivated area globally, which would increase demand for fertilizers. According to the International Fertilizer Association (IFA), the volume of NPK fertilizer used globally grew from 157 million tonnes in 2009 to 188 million tonnes in 2016, or by an average of 3% per annum (Figure 1). Growth rate is expected to moderate to 2% p.a. between 2017 and 2020.

Over the same period, global fertilizer production grew from 163 million tonnes to 201 million tonnes, representing an annual growth of 2.1%. This is expected to accelerate to 2.3% p.a. between 2017 and 2020 (Table 1). Nitrogen is the most synthesized and consumed fertilizer element, accounting for 60% of the total. China is the world’s largest producer and consumer of chemical fertilizers, and in 2016, the country accounted for 25% and 28% of the global market share, respectively (Figure 2).

Between 2012 and 2016, the world’s biggest exporter of fertilizer was Russia which accounted for 15.9% of global exports. This was followed by Canada (13.4%), China (13.3%), Belarus (6.4%) and the United States (5.6%). In terms of imports, the United States was the most important market (13.4% share), followed by Brazil (13.2%), India (10.5%) and China (5.7%).

Thailand was in 47th place in exports (0.1% market share) but in 7th place in imports, accounting for 2.9% of global imports (Figure 3).

In Thailand, the fertilizer sector is a downstream industry that depends almost entirely on imports for inputs. These are split into two groups: (i) 62.1% of imports are straight fertilizer[1], comprising nitrogen (48.7%) from Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Malaysia and China, potassium (13.4%) from Canada, Belarus, Israel and Germany, and phosphorus (0.1%) from Egypt and China. Fertilizer manufacturers import these chemicals to mixing with fillers to the required quantity and proportions (with at least two of the major nutrients included). The bulk of this output is consumed in the domestic market, and about 5% is exported, with most (85%) going to neighboring countries Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar, and Vietnam. Domestic production (as opposed to mixing) of fertilizers is limited to only a few products, including ammonia and ammonium sulfate, is estimated at 800,000 tonnes annually. (ii) 37.9% of imports are finished or semi-finished compound NPK products to be mixed and packed for distribution to wholesalers and retailers (Figure 4). The most important import sources are China, Russia, South Korea and Norway (Table 2).

The most commonly consumed fertilizers are urea (46-0-0), ammonium sulfate (21-0-0), and fertilizer mixes 16-20-0, 15-15-15, 16-16-8, and 13-13-21. These have a broad range of uses, including in rice, fruit, and other crops. They account for a combined 90% of the domestic fertilizer market. Fertilizers that are produced and distributed in the domestic market are licensed and checked for quality by the Department of Agriculture, as required by the Fertilizer Act B.E.2518 (1975) and amended Fertilizer Act B.E.2550 (2007).

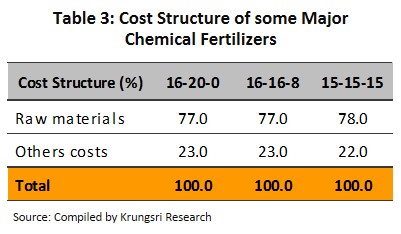

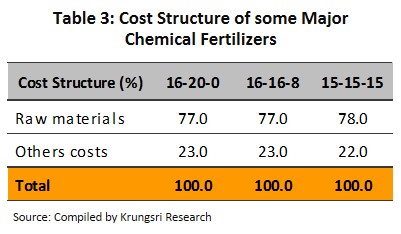

Industry cost structure: about 80% is for the purchase of raw material such as urea, diammonium phosphate and potassium chloride (Table 3), most of which needs to be imported. The remaining 20% of costs goes to other items such as power and transportation. Given the large proportion of overheads arise from imports, overall costs are dependent on the direction of import prices, which in turn determined by world markets. The variable exchange rates add to the overall uncertainty. At the same time, it is difficult for manufacturers to compensate for higher costs by raising selling prices because, in line with the Prices of Goods & Services Act B.E.2542 (1999), fertilizer prices are controlled by the government through The Department of Internal Trade’s central committee on goods and services. The committee sets recommended prices for some types of fertilizer, and manufacturers and retailers of these fertilizers are not permitted to sell at above these prices. This has pressured margins, especially for importers of mixed fertilizers because they cost more than straight fertilizers. Hence, operators would try to increase their income by pushing up distribution volume.

Annual demand for chemical fertilizer reached 4.5-5.5 million tonnes in 2014-2018. This falls into two groups.

(i) 2.0-2.5 million tonnes of straight fertilizers with nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium as base plant nutrients (Figure 5) were sold annually during the period, and about 60% was nitrogen-based fertilizer because this is the main product applied during the initial stages of plant growth (nitrogen promotes stronger and faster plant development). Phosphorus (P) and Potassium (K) contributed 19% and 21% of sales, respectively.

(ii) Almost 3 million tonnes of various mixed fertilizers were sold each year in this period.

The largest share was applied to rice crop (51% of all chemical fertilizers) but this is because over 80 million rai of land in Thailand is designated for rice cultivation. This is followed by sugarcane (9% of all chemical fertilizers), rubber (8%), oil palm (7%), maize for animal feed (6%), cassava (5%) and other crops (14%) (Figure 6). But

in terms of quantity applied per rai, oil palm and rubber were the most heavily fertilized crops, followed by sugarcane, off-season rice, maize, cassava and first season/rainy-season rice (Figure 7). Given this, changes in total cultivation area of these commercial crops will have a direct impact on demand for chemical fertilizers.

In 2018, there were 709 fertilizer producers registered with the Department of Business Development. Of this, 697 (or 98%) were SMEs and only 12 (or 1.7%) were large-scale operations. But the latter controlled 55% of the market (Figure 8) because their production costs are lower, they are able to win large contracts to distribute through government channels, and they can afford to run regular marketing campaigns. Meanwhile, SMEs have restricted ability to expand output given the uneven quality of their goods.

Looking at distributors (wholesalers of synthetic fertilizers and other agricultural chemicals), over 99% of the country’s 1,423 operations are small-size (Figure 9) and they are spread throughout Thailand. Given the relatively low cost required to set up the distribution business and operations are straightforward (source goods from manufacturers and importers and sell to buyers), there are low barriers of entry. This is led to intense competition. Some operations also act as both wholesalers and retailers, while some re-export goods especially to neighboring countries. Against this backdrop, large operations have the following advantages :

- They buy in larger quantities, which normally means lower per-unit cost. The majority of large distributors are also subsidiaries of manufacturers or have agreed supply contracts with them. Hence, they have more favorable negotiating position.

- They have good relationship with the local farming communities and strong negotiating position when dealing with local buyers.

- They carry a wide range of stock to meet the demands of growers of different crops at different times of the growing season. So, sales are more stable throughout the year.

Situation

Overall domestic demand for fertilizer largely depends on total planting/yields of commercial crops, especially rice and rubber which together occupy over 60% of all crop land in Thailand. The changing climate and irrigation water level could also influence demand because they determine how much of a given crop is cultivated in any year. Below, we look at demand for fertilizer in recent years.

- 2009-2013: Demand for fertilizer rose steadily because the rice pledging scheme had encouraged farmers to increase rice yields as much as possible. However, farm prices were also high for other crops, especially rubber. So, growers developed more rubber plantations during the period. This raised demand for fertilizer to an average of 5.9 million tonnes per year.

- 2014-2016: Following the boom years, the country experienced its lowest rainfall in a decade and the subsequent severe drought forced farmers in many areas to hold back on planting. Specifically, it discouraged rice planting because the crop requires a lot of water. As a result, the total area under cultivation nationwide slipped from 81 million rai in 2013 to just 68 million rai in 2015. Additionally, low farm gate prices had suppressed demand for fertilizer. Demand shrank from 6.2 million tonnes in 2013 to 4.6 million tonnes in 2015 before inching up to 4.8 million tonnes a year later (dropping by an average of 7.5% per annum). As such, in 2015, imports of fertilizer dropped to 4.9 million tonnes (down 9.7%), the lowest level in 7 years.

- 2017-2018: Following the drought, water levels and the overall weather returned to a more favorable state. This boosted agricultural activity and lifted demand for fertilizer in 2017 by 8.2% to 5.3 million tonnes. However, in the first half of 2018, flooding in the northeast of the country interrupted farming activity in the area, especially rice cultivation which suffered significant losses. This reduced total fertilizer consumption to 5.0 million tonnes in 2018. However, fertilizer exports to the CLMV nations jumped 28.5% in 2017 and by 31.0% in 2018 as these countries expanded cultivation area of cash crops, especially rice, cassava and sugarcane.

- 2019: Total cultivated area for cash crops was close to 2018 level, which supported demand for fertilizer throughout the year. The better availability of irrigation water (Figure 11) also helped to increase yields of oil palm, cassava and rubber (Figure 12), crops that typically demand heavy applications of fertilizer. However, flooding in the northeast again hurt rice growers in the region, who lost a portion of their crops. And in both the north and northeast, the delayed monsoon season had reduced yields in areas that are not served by the irrigation canals. Beyond this, the economy continued to suffer from weak growth and soft prices for important crops such as oil palm and rubber. These reduced the ability of farmers to invest in more inputs, and so demand for fertilizer slipped. Krungsri Research estimates that in 2019, total demand for fertilizer would reach 5.0-5.1 million tonnes, up 0-2% from 2018 figure.

Fertilizer exports tumbled in 2019. Export volume fell 21.7% to 597,475 tonnes and export value dropped by 25.8% to THB5.9bn. This was partly due to the high base a year ago, and partly because the CLMV market (Figure 15) were also experiencing a softer economy, and flooding which hurt yields in some areas.

Domestic prices for most fertilizers[2] fell in 11M19, with the exception of urea (applied in rice and all other crops) and 13-13-21 fertilizer (used to accelerate plant growth and improve yields) which prices rose by 4.1% YoY and 0.3% YoY, respectively (Table 4). The weaker prices were partly due to the government’s request for producers to reduce selling prices of ready-mixed fertilizers, to ease the financial burden on farmers, in a period of rising costs for raw fertilizer in world markets. This should dampen profits in 2019 for manufacturers and producers.

Outlook

Overall, the fertilizer industry will see slow but steady growth between 2020 to 2022. Krungsri Research estimates the industry would grow by an average of 1-2% per year over these 3 years (Figures 17). This is supported by the following:

- Prices of major Thai crops should be similar to 2019 levels. World prices have been stable or risen slightly for some crops (Figure 18), which would prompt Thai farmers to increase planting. This would be especially true for rice (more than half of all the farmed land in Thailand is planted with rice) which is benefitting from highest prices for jasmine rice since 2017. Krungsri Research forecasts that in 2020, total are planted with the main cash crops will increase, and yields, too, especially for rice, maize and cassava, which together account for 60% of total demand for fertilizer (Table 5). The government may also introduce more measure to help the agricultural sector, for example by offering price guarantees for some crops. This would lift spending power and improve farmers’ confidence, and they would be incentivized to maintain their cultivated area. Thus, demand for fertilizer would remain relatively stable throughout 2020-2022.

- Weather will be more favorable for the agricultural sector. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)[3] gives a 50% chance that global rainfall will be normal in 2020. Nevertheless, the negative effects of a weak El Niño in 2019 and the subsequent drought have carried over into 2020.

There is insufficient stored water to support off-season irrigation especially in the north and central regions of the country. Drought conditions will continue throughout the first half of the year, which would affect rice planting in these regions between January and April. But, these will not have significant impact on both total area cultivated nationwide and net demand for fertilizer. For 2021 and 2022, the weather should improve, as it did following the drought in 2010 and 2015, when farming water levels returned to normal levels within 1 or 2 years (Figure 19-20).

However, if rainfall is lower than normal or if it falls below the NOAA forecasts, it will reduce demand for fertilizer in 2020, and demand would drop by 4-6% from 2019 levels, before recovering in 2021-2022.

Against a backdrop of higher global prices for fertilizers which are raising import costs and larger fluctuation in currency exchange rates, demand for fertilizer will grow only gradually. However, because fertilizer use determines agricultural productivity, the government will protect the interests of farmers by limiting price the selling prices charged by manufacturers and distributers. This means operators need to look elsewhere to increase income and make their businesses more secure, and try to increase income by expanding distribution channels. This can be achieved in several ways:

- Expanding customer base by offering customized fertilizer mix: This can be done by investing in the appropriate technology to analyze soil samples. This will allow manufacturers to customize fertilizers to specifications desired by individual farmers, and in the process, they will be able to add more value to their products. This will support the wider adoption of smart farming and offer farmers access to products that are customized for use in a particular environment. This could be a main growth driver for the industry in the future.

- Increasing exports to the CLMV nations: The CLMV countries are trying to expand their respective agricultural sectors by increasing cultivated area for the main cash crops (i.e. rice, oil palm, rubber, maize and cassava). The output would be exported or sold used as input by other agro-processing industries, including rubber processing and the production of animal feed. This will stoke additional demand for fertilizer. The latest data available (2016) show that Thailand’s share of all imports of fertilizer to the CLMV zone has risen to 4.6%, up from an average of just 1.8% during 2009-2015. In Myanmar, the rise has been especially dramatic, jumping almost two-fold from 9.7% of import value in 2016 to 18% in 2017. However, Thai players need to break into the CLMV market and build brand awareness rapidly because although there are currently only a few fertilizer manufacturers in these countries, Thailand’s main competitor is China, which already has almost 50% market share, while the fertilizer production process is relatively straightforward. And so in the coming period, there is likely to be an increasing number of operators (based in the CLMV countries and elsewhere) that are looking to build profits by grabbing a share of the CLMV market. This means competition could intensify in the near future.

Potential challenges. In addition to the sluggish global and Thai economies, and uncertain weather conditions over the next 3 years, pressuring the agricultural sector’s purchasing power arising, they may also be affected by the growing consumer interest in organic food products[4], and in Thailand, the Department of Agriculture reported that in 2017-2018, total farmland that meets organic standards[5] had risen from 231,000 to 357,000 rai (54.5%). At the same time, the government has set out a plan for 2018-2022 with the intention of expanding the total area of organic cropland in the country to 1,300,000 rai by the end of this period. Beyond this, to reduce costs, some farmers are using bio-fertilizers together with chemical fertilizers, and trends such as this will reduce demand in the future.

Krungsri Research’s view

Between 2020 and 2022, earnings of fertilizer manufacturers and distributors would remain at levels close to those recorded in 2019. However, competition might increase with a greater number of new operators entering the market. Meanwhile, government price controls means it will be difficult for players to raise selling prices. Hence, profits would be capped.

Fertilizer manufacturers: Income growth should be similar to 2019, supported by greater demand arising from an expansion in total cultivated area. But there will be headwinds: (i) prices in the agricultural sector will likely remain low, which would dampen farm income and purchasing power; (ii) a possible weakening of exchange rates would have an impact on cost of imports; and (iii) government price controls for fertilizers distributed in Thailand would cap price increases by manufacturers. Within the market, large manufacturers will have an advantage over SMEs. The former are better able to control costs and are in a better position to expand into overseas markets, especially the CLMV zone.

Fertilizer distributors: SMEs will have to contend with rising competition because low entry barriers would encourage more players to enter the market. SMEs also have smaller capacity to carry a wide range of stock and their distribution costs would be higher. Because of this, SMEs need to manage inventories carefully and systematically to match demand. For their part,

fertilizers importers may have to contend with higher costs because of the need to hedge against currency fluctuations. This would increase import costs, and reduce their profitability.

[1] Thailand has sources of potassium in Udon Thani, Sakon Nakhon, and Nakhon Ratchasima provinces. These have the potential to be commercially viable but as yet measures have not been found to protect against the negative impacts of mining, while the costs of extraction are somewhat high and so instead, potassium is imported into Thailand.

[2] Namely urea (46-0-0), ammonia sulfate (21-0-0) and 16-20-0, 15-15-15, 16-16-8 and 13-13-21 fertilizers, which together comprise over 90% of fertilizer used in Thailand (by volume)

[3] Analysis by NOAA of data covering the last 60 years shows that strong EI Niño (below average rainfall) and strong La Niña (above average rainfall) occur on average every 12-15 years. The last strong La Niña was in 2010-2011 and the last strong El Niño was in 2015-2016. In 2019, weak EI Niño conditions emerged but these had only limited impacts on agriculture.

[4] Organic farming emphasizes the use of organic fertilizers such as manure, compost, green manure, and bio-fertilizer to feed crops and to ensure their health and so make them stronger, healthier, and better able to defend themselves from infection and pests.

[5] Implemented by Organic Agriculture Certification Thailand (ACT) - International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movement (IFOAM)

.webp.aspx)