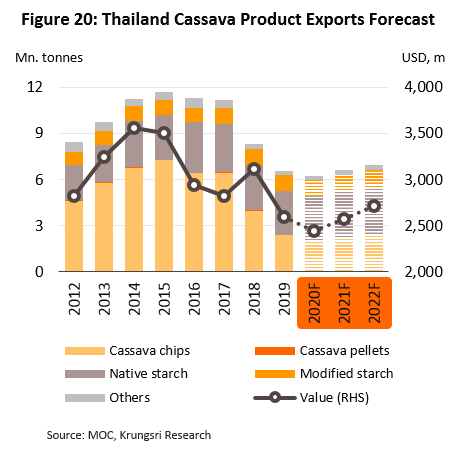

Between 2020 and 2022, the cassava industry will see limited growth because although domestic consumption is expected to rise, exports – which normally account for 64% of Thailand’s cassava products – will drop principally due to weaker demand in China. The latter will be triggered by: (i) the shift from importing cassava to running down China’s domestic corn stock, which would push downstream industries (especially producers of animal feed and ethanol) to switch from cassava to corn input; (ii) lower demand for cassava as input for animal feed following the African Swine Fever and subsequent culling of livestock; and (iii) China investors increasing investing in the cassava industry overseas, to increase supply security for its ethanol manufacturers. However, the outlook remains positive for producers of modified cassava starch, a high-value-added product that will see rising demand from food processors and manufacturers of cosmetics and medicines.Between 2020 and 2022, the cassava industry will see limited growth because although domestic consumption is expected to rise, exports – which normally account for 64% of Thailand’s cassava products – will drop principally due to weaker demand in China. The latter will be triggered by: (i) the shift from importing cassava to running down China’s domestic corn stock, which would push downstream industries (especially producers of animal feed and ethanol) to switch from cassava to corn input; (ii) lower demand for cassava as input for animal feed following the African Swine Fever and subsequent culling of livestock; and (iii) China investors increasing investing in the cassava industry overseas, to increase supply security for its ethanol manufacturers. However, the outlook remains positive for producers of modified cassava starch, a high-value-added product that will see rising demand from food processors and manufacturers of cosmetics and medicines.

Overview

Cassava is a carbohydrate-rich crop that has a wide range of uses in the 4F’s: Food (for human consumption), Feed (for animals), Fuel (to produce biofuel & ethanol), and Factories (to make alcohol, citric acid, clothing, medicine, paper and chemicals).

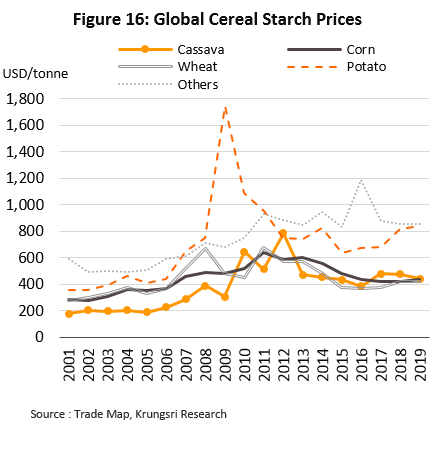

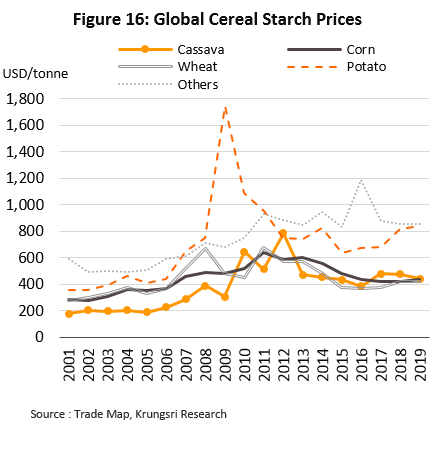

For years, cassava has been cheaper than other starchy crops and has any industrial uses. These stoked demand in world markets, and cassava became the 5th most important crop in the world, after wheat, corn, rice and potatoes.

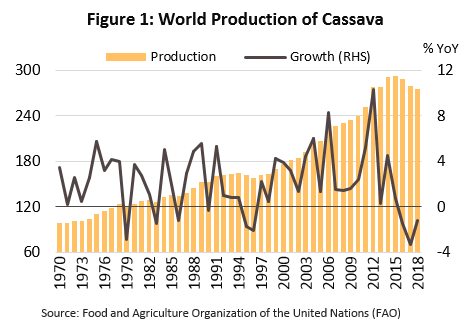

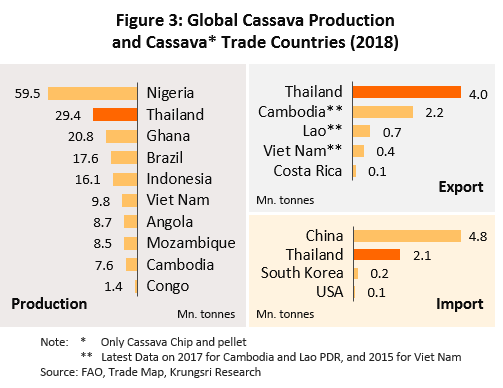

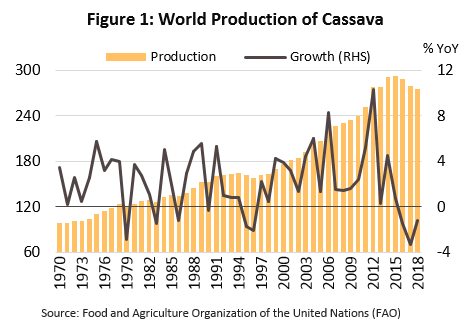

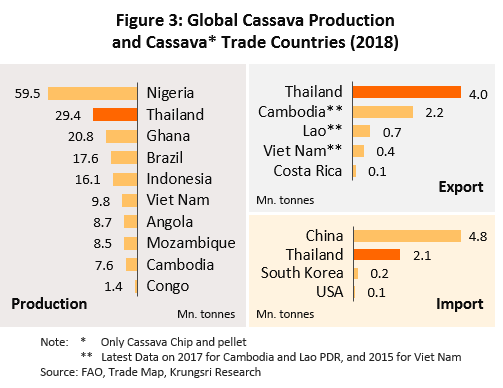

In 2018, 275 million tonnes of cassava were produced globally (Figure 1). Contributing 61.1% of the total, Africa was the most important cassava-producing region, followed by Asia[1] (29.0%), the Americas (9.8%) and Oceania (0.1%). By individual country, Nigeria was the world’s biggest producer, at 21.6% of global output, followed by Thailand (10.7%), Ghana (7.6%), Brazil (6.4%) and Indonesia (5.9%) (Figure 3). However, heavy investment by Thai and Chinese players in cassava production in Vietnam and Cambodia meant that output in these two countries have risen rapidly over the last 10-15 years.

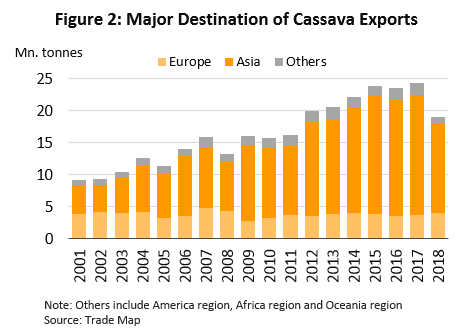

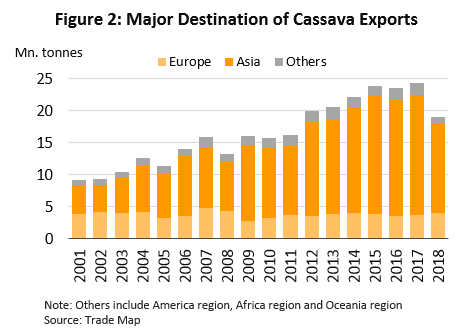

Although Africa is home to the world’s most important cassava-producing nations, Africa’s output is largely for domestic consumption. In these countries, cassava plays an important role in supporting local food security and economic activity, and ensuring recurring income for the farmers. The main products are fresh cassava root and processed cassava products. By contrast, in Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam, production is targeted for export. Hence, these countries are among the world’s most important exporters of cassava products (Figure 3). The global markets for cassava[2] are largely driven by demand from Asia, especially China, which alone accounts for 36.5% of global cassava imports.

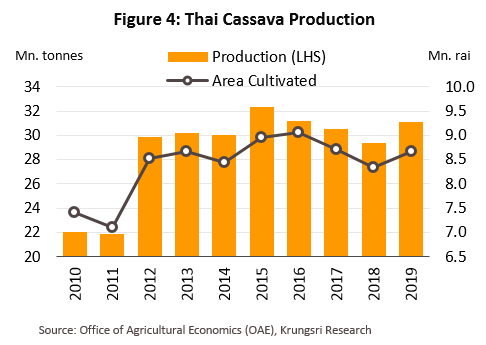

Over the past two decades, rising demand in export markets has fueled the expansion of Thailand’s cassava processing capacity, and through this, a steady increase in the size of the national cassava harvest.

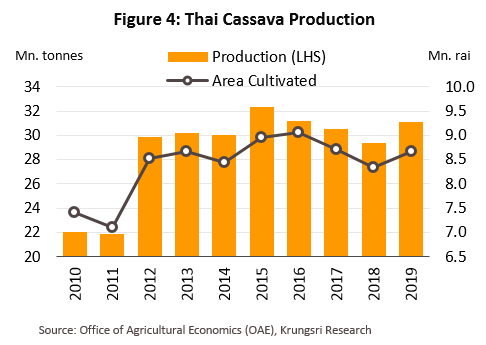

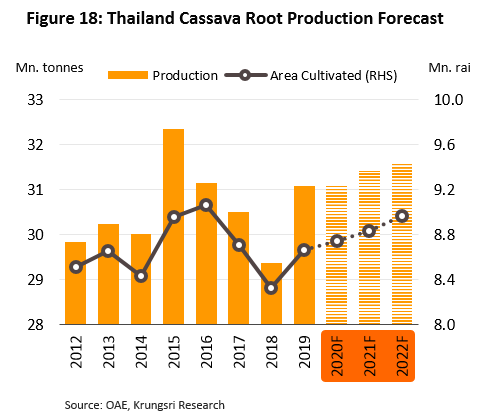

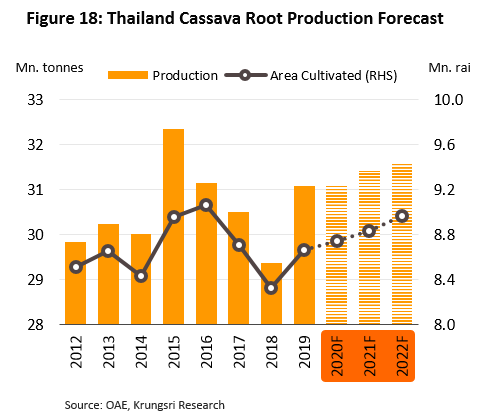

Over the past two decades, rising demand in export markets has fueled the expansion of Thailand’s cassava processing capacity, and through this, a steady increase in the size of the national cassava harvest. In 2019, 8.7 million rai of Thai farmland was planted with cassava. This yielded 31.1 million tonnes of raw product[3] (Figure 4). Cassava cultivation is clustered most heavily in Nakhon Ratchasima (17.3% of national cassava farms by area), followed by Kamphaeng Phet (7.5%), Chaiyaphum (6.4%) and Kanchanaburi (5.9%).

In 2019, Thailand was home to 423 cassava processing facilities[4], but for convenience and to save on transportation costs, these are generally located close to cassava farms. Hence, Nakhon Ratchasima has 39 factories, the most in Thailand. Some Thai players have also set up basic processing factories in areas with easy access to cassava input imported from neighboring countries, especially Lao PDR and Cambodia. There are 39 cassava factories in Kalasin, 33 in Udon Thani and 21 in Khon Kaen. And there are another 33 factories in Chonburi, which offers quick access to major ports for export (Figure 5).

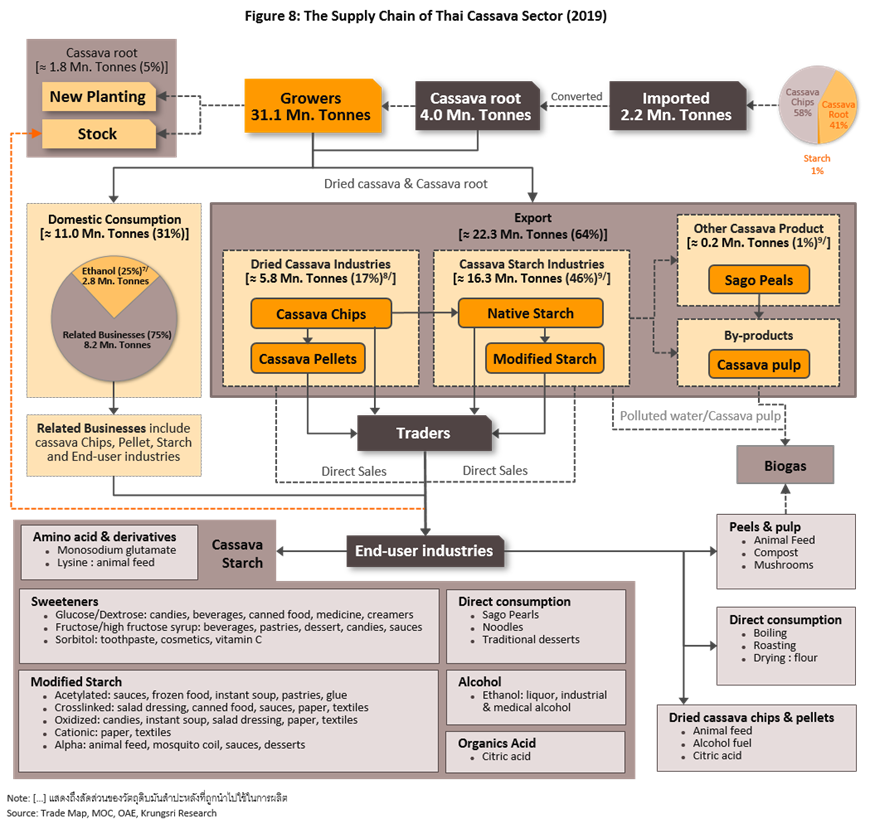

Thailand produces two major groups of cassava products:

- Dried products: In this group, cassava chip is the most important. It is an input for the manufacture of animal feed, alcohol and citric acid. Thailand is currently home to 307 factories that produce dried cassava goods, and of this, 235 (or 76%) produce cassava chips. Another 39 (13%) process cassava pulp, 11 (4%) produce cassava pellets, 6 (2%) manufacture dried crushed cassava, and 16 (5%) produce other types of dried cassava goods.

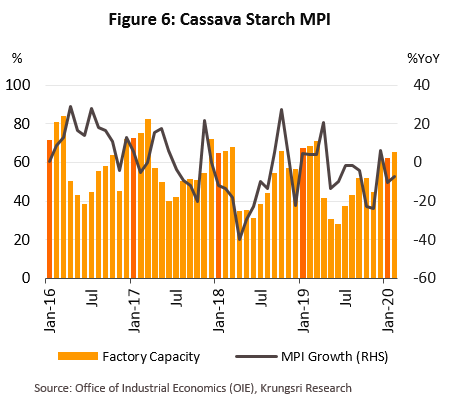

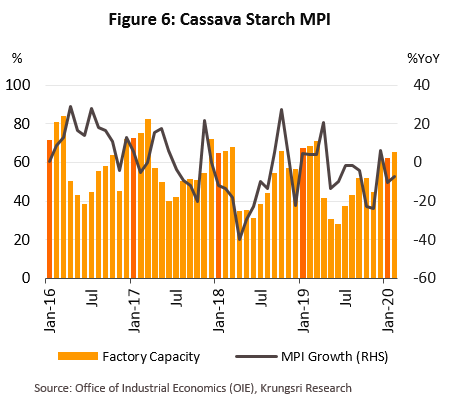

- Tapioca/cassava starch: The initial output of cassava starch is ‘native starch’ which can be used directly for human consumption as an ingredient or flavoring, or used in the manufacture of ‘modified starch[5]. The latter is a value-added product that is an input for a wide variety of downstream products, such as monosodium glutamate, sweeteners, sauces, cosmetics and medicines. Currently, there are 102 cassava starch processing factories in Thailand and 14 that produce modified starch. The initial processing of cassava into starch normally occurs at the end of the year or the start of the following year, after the main harvest season (Figure 6).

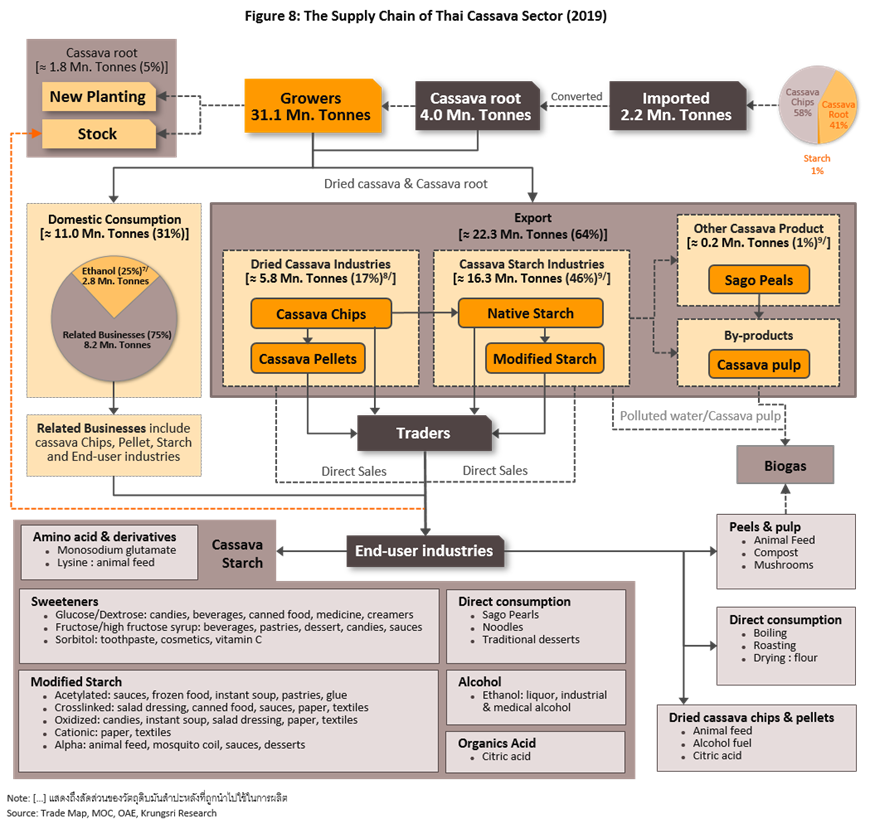

In 2019, 89% of input for Thailand’s cassava processing industry was sourced domestically (Figure 8), and 11.4% was imported mostly from neighboring countries which supplied 1.3 million tonnes of cassava chip[6], 0.9 million tonnes of fresh cassava, and a small volume of native starch, modified starch and sago. In total, 36% of the input for the Thai cassava supply chain are used to produce goods for domestic consumption, and 64% goes to goods that are supplied to export markets. Almost all fresh cassava root is converted into cassava chip, cassava pellet, starch and ethanol for use in downstream industries.

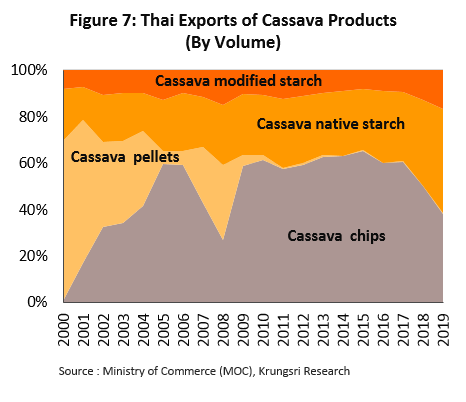

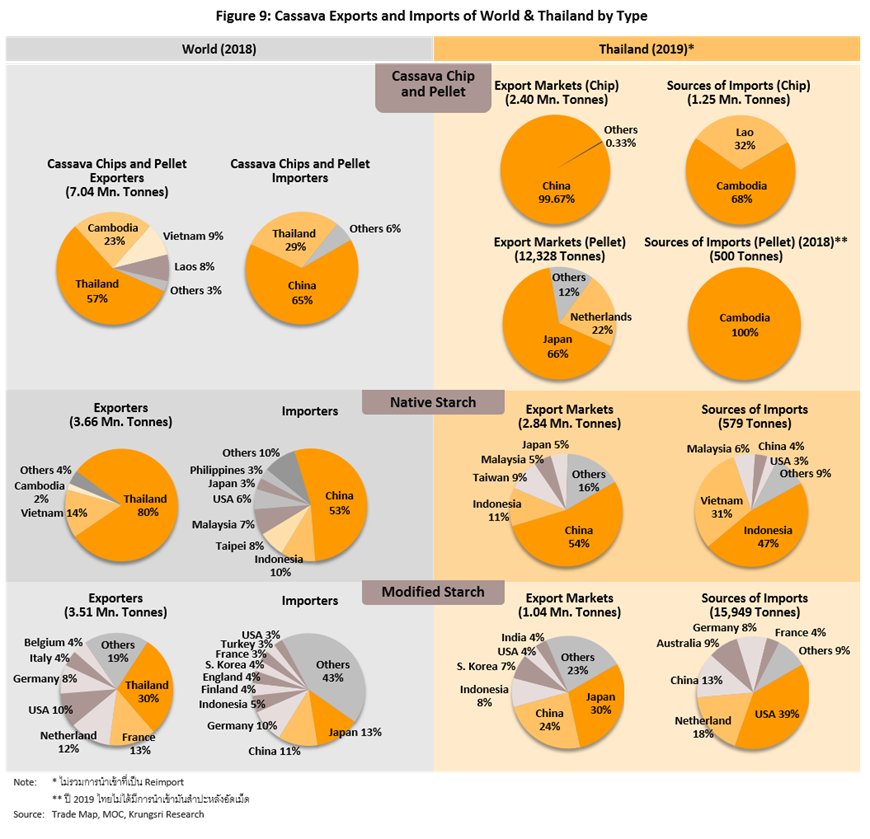

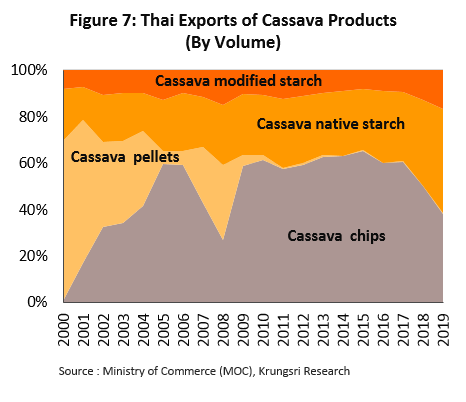

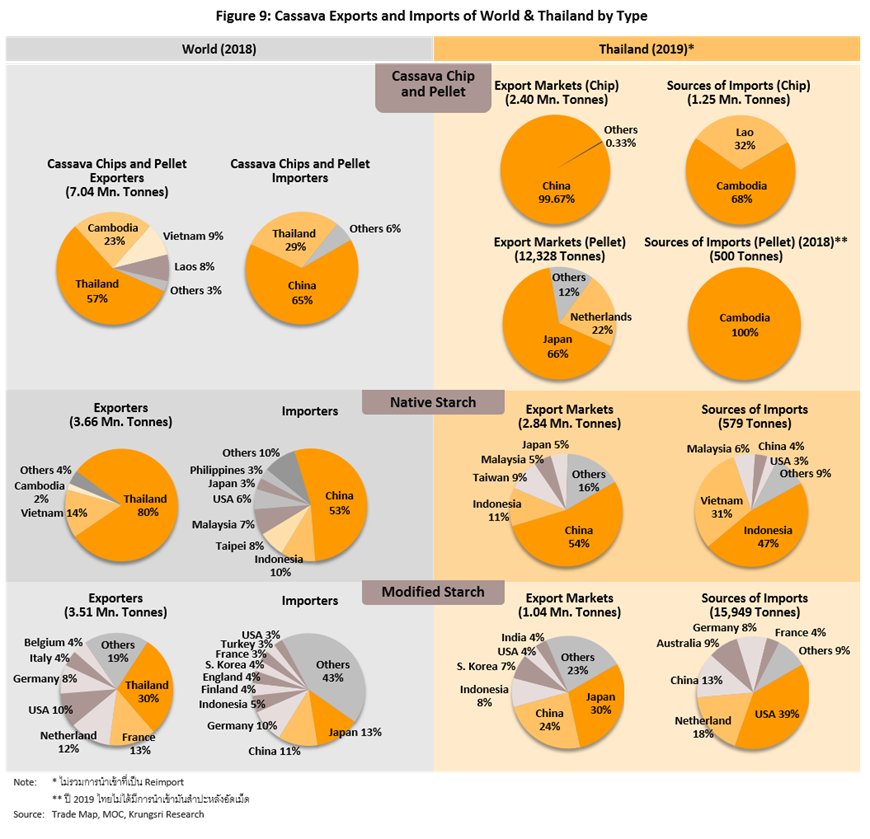

Because of its highly developed cassava industry, Thailand is the world’s leading exporter of cassava products. The country supplies 80% of global exports of native starch, 57% of exports of cassava chip, and 30% of exports of modified starch. However, Thai exports of cassava pellet have dropped drastically following the 2005 decision by the EU to stop importing that product (Figure 7) and to switch to alternatives. The EU policy also profoundly altered the structure of Thai exports, which moved from relying on exports to Europe to almost total dependency on Asian markets, especially China which accounts for 64% of Thailand’s exports of cassava products (Figure 9).

- Native starch: This accounted for 43.2% by volume of all exports of cassava products from Thailand in 2019, the main markets for this being China (54% by value of all exports of native starch in the year), followed by Indonesia (11%), Taiwan (9%), Malaysia (5%) and Japan (5%). The exact state of the export markets depends to a large degree on the health of downstream industries, such as food processing, paper production, beverage, and textiles.

- Cassava chip: Another 36.6% of exports of Thai cassava products (by volume) is cassava chip. Almost 99% of this went to China which uses that to produce animal feed[10], alcohol, citric acid and ethanol. However, the structure of the export market and the extreme concentration of purchasing power means that Thai suppliers have weak bargaining power but are also exposed to significant risk if China changes its sourcing policy. This was what happened in 2019 when China cut imports of cassava chip and switched to using domestically-grown corn, which had significant knock-on effects on Thai exporters.

- Modified starch: This is a high-value-added product that accounts for 15.8% (by volume) of Thai cassava exports. Demand for modified starch normally moves in line with the outlook for downstream industries, such as cosmetics and medicines. The main export markets are Japan (which accounted for 30% of 2019 exports of modified starch by value), China (24%), Indonesia (8%) and South Korea (7%).

- Cassava pellet: The 2005 decision by the European Union[11] to reduce imports of cassava pellet had profound impact on Thai producers, and exports have dropped since. In 2019, pellets contributed 0.2% of Thai cassava exports.

- Other cassava products: The remaining 4.2% of exports come from a mixed bag of products, including cassava root, sago (made from tapioca) and cassava pulp. The principal markets for these are South Korea (32% of exports in 2019), New Zealand (22%), China (16%) and Turkey (15%).

Domestic uses of cassava. Apart from being consumed by households and as input to produce animal feed, cassava is also a raw material in other industries, including food processing and in the production of beverages, medicines, cosmetics, chemicals and alcohol. Large players have also invested in downstream industries, including ethanol production and plants to generate bioenergy from cassava pulp and other waste products, which is for own use as well as distributed commercially (Table 1).

Situation

Between 2012 and 2017, the Thai cassava industry experienced a period of sustained expansion led by 16.6% annual growth in exports, driven by demand from China. This boom was based on several factors which are described below.

- Demand from China producers of animal feed rose steadily throughout this period, in line with strong economic growth. Demand was also boosted by official support for the establishment of ethanol refineries in southern China. These were set up as part of the national plan to develop ‘1.5G’ biofuels, to reduce dependency on oil imports and to address problems with air pollution. This also triggered a significant increase in imports of cassava chip for use as input for the ethanol factories.

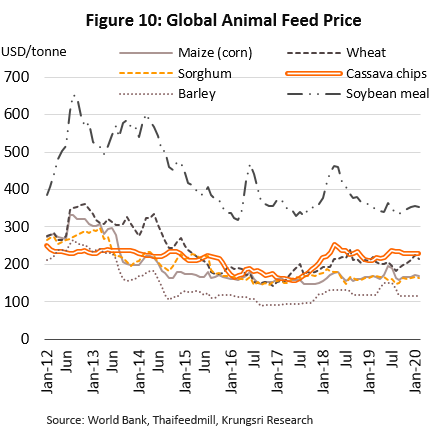

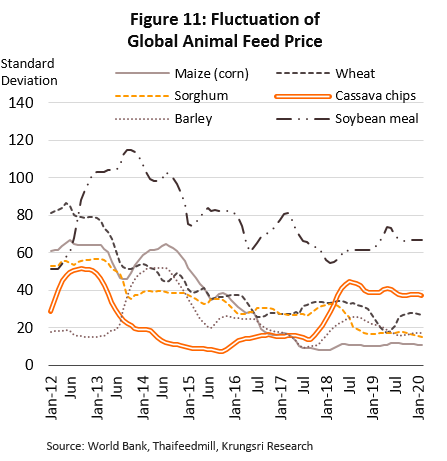

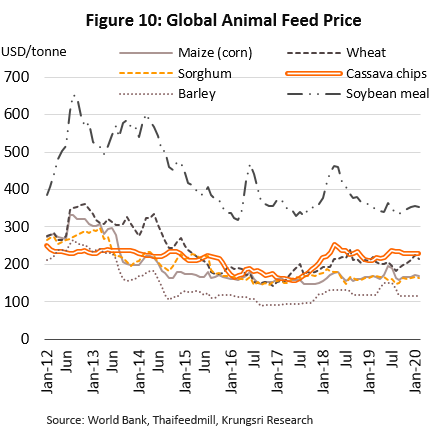

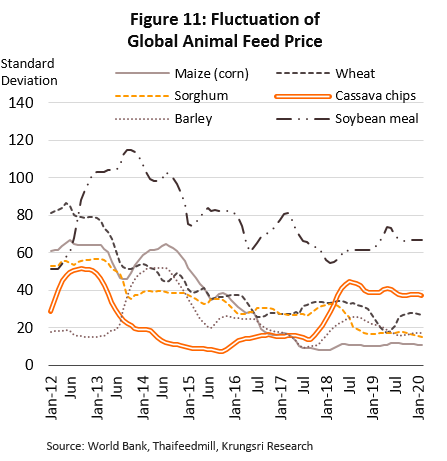

- Demand for industrial use in China also rose because cassava was cheaper than other major carbohydrate-rich crops (Figure 10) but provides higher energy yields. And, its price was more stable than for other commodities such as soybean meal, maize, wheat and sorghum (Figure 11), making cost-control easier for industrial consumers.

- Thai exports of cassava also benefited from China’s agricultural policies (i) Food security – introduced in 2008, this policy restricted the use of corn to produce animal feed only. As a result, there was a surge in demand for imported cassava to manufacture products including alcohol, citric acid and ethanol. (ii) Support agricultural prices and protect corn growers. China imposed 65% tariff on corn imports, most of which originated from the US, and zero tariffs on Thai cassava, as required under the ASEAN-China Free Trade Agreement (ACFTA). This naturally made imported Thai cassava extremely cheap relative to corn imported from western producers.

However, the outlook for the cassava industry has changed since 2015, with business conditions worsening. In response to low global prices for other crops that made them attractive alternatives (Figure 10), exports of Thai cassava grew only 4.3% in 2015, and fell by 3.6% in 2016 and 0.7% in 2017.

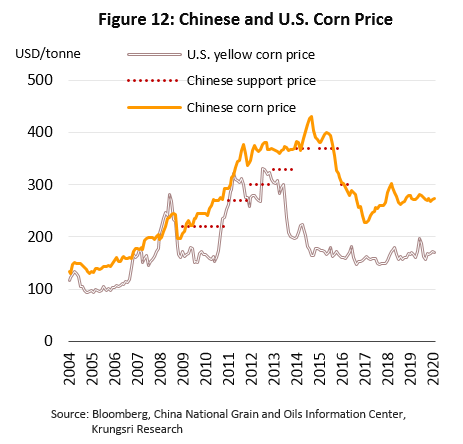

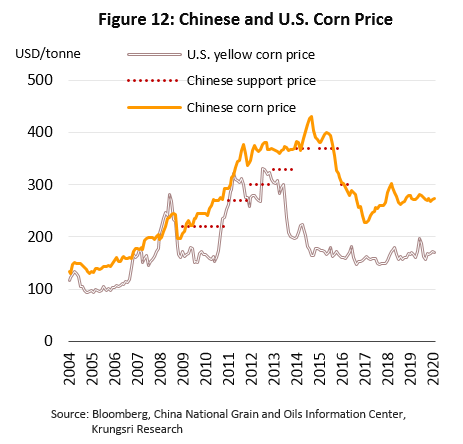

Price of Chinese corn also fell sharply in the last few years, after the Chinese government abandoned its price guarantee program in 2016. The price of corn has fallen from a high of USD431/tonne in the third quarter of 2014 to only USD273 currently (Figure 12). This undercut the competitiveness of Thai cassava.

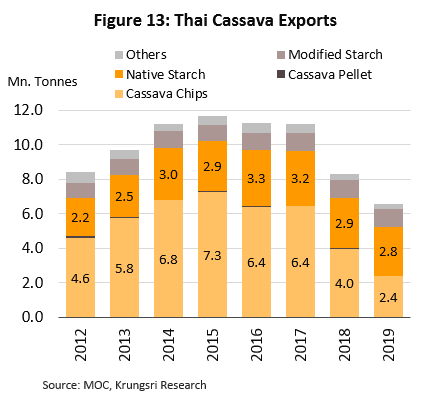

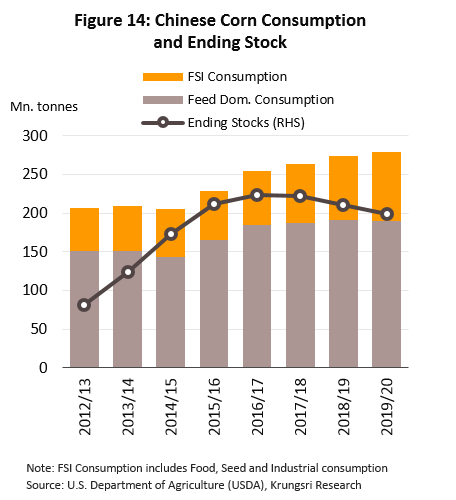

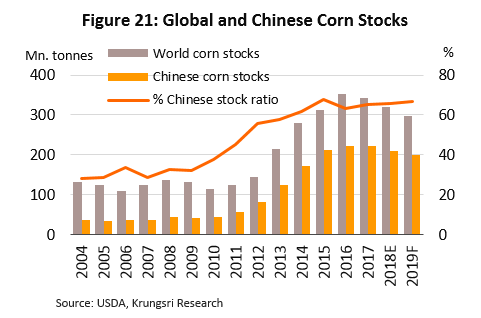

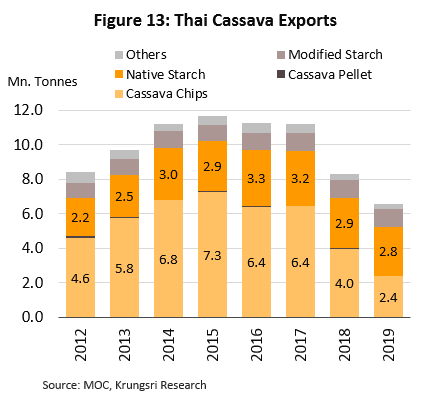

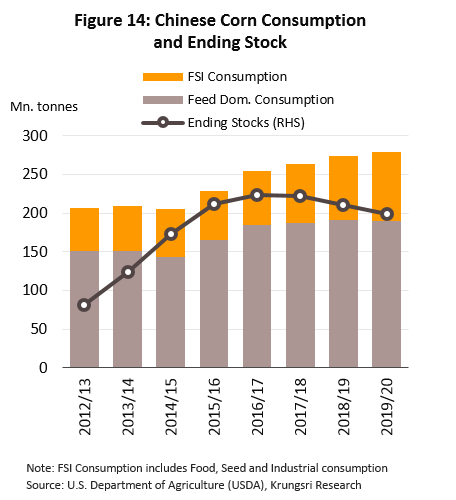

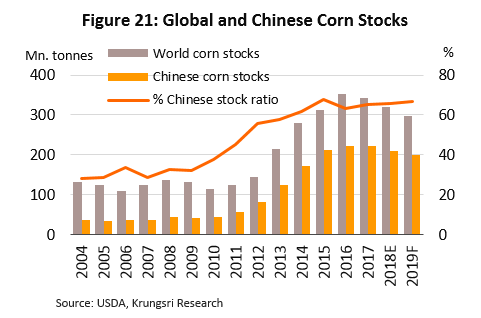

In 2018, the Thai cassava industry saw weak conditions in export markets. Exports to China were exceptionally bad that year (Figure 13) because of: (i) the decision by China to encourage the consumption of corn as they tried to reduce domestic corn inventory, which had risen to almost 200 million tonnes (Figure 14). This drove some ethanol refineries to stop production or to alter production processes so they could use corn instead of cassava as primary input; (ii) a drop in demand for animal feed (and cassava input) after the African Swine Fever (ASF)[12] forced the culling of a significant size of China’s pig herd; and (iii) the continued drop in the prices of substitute crops. As a result of these factors, exports of Thai cassava products fell by 26.1% to 8.3 million tonnes in 2018; exports of cassava chips registered the largest drop of 38.1% to 4.0 million tonnes, down from 6.4 million tonnes in 2017.

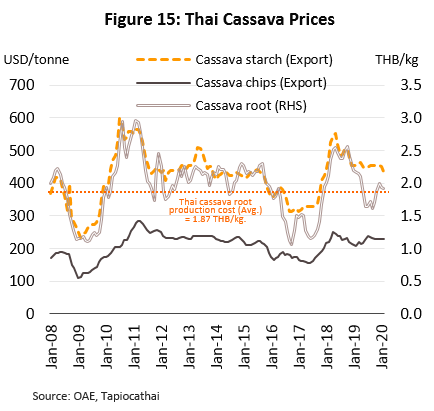

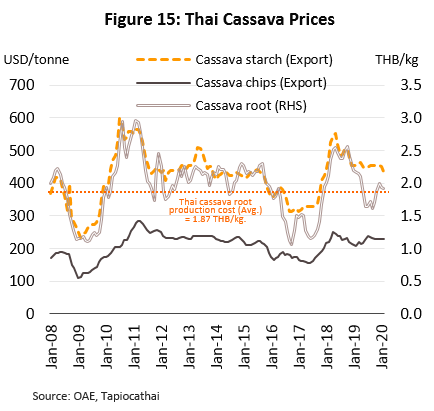

Domestic production reached 29.4 million tonnes in 2018, down 3.7%. Since 2016, low prices had encouraged farmers to plant different crops, so output had been falling for some years. In 2016-2017, prices averaged only THB 1.4-1.8/kilogram, which was lower than production costs[13]. Drought also had an impact on the size of the harvest. However, domestic demand remained strong and this ate into cassava stock. This pushed up domestic prices for fresh cassava and in 2018, they rose by 69.7% from 2017 level to THB2.38/kilogram. As a result, export prices for all cassava products also rose, which lifted the total value of exports by 10.4% to USD3.1bn even though export volume fell steeply.

In 2019, the industry suffered the twin impact of an increase in supply and falling demand in export markets.

- Cassava production rose to a 3-year high in 2019, by 5.8% from 2018 level to 31.1 million tonnes. This is a notch below the historic high of 32.4 million tonnes in 2015. Following higher cassava prices, farmers were incentivized to expand area under cultivation (Figure 15). The Office of Agricultural Economics estimates the total area planted with cassava rose by 4.1% in 2019 to 8.67 million rai. A more favorable climate and greater supply of water also helped, lifting yields to 3,586 kilograms/rai (up 1.7%).

- Orders from overseas dropped markedly in 2019, especially due to China’s policy to reduce imports of cassava. Overall, Thai cassava exports shrank by 20.7% to 6.6 million tonnes from 2018 level of 8.3 million tonnes. The situation for individual product groups is given below.

- Native starch: Exports reached 2.8 million tonnes (down 3.5%), bringing in USD1.2bn receipts (down 10.7%) in 2019. Exports were undercut by falling prices for other crops, especially corn and wheat (Figure 16) which are close substitutes for cassava in some downstream industries, including food processing, beverage, paper, glue, textiles and plywood. Unfavorable market conditions also pushed down prices realized by Thai exporters by 8.2% to USD439/tonne.

- Cassava chip: Export volume and value fell by 39.8% and 41.5%, respectively, to 2.4 million tonnes and USD520.9m. As described above, this was due to (i) China’s policy to reduce domestic corn stock by ending its price guarantee scheme and allowing industrial consumers to switch to corn (from cassava) as main input, and (ii) the ASF outbreak, which cut demand for animal feed. Export prices also weakened in the year and dropped by 2.6% to USD221/tonne.

- Modified starch: This product held its ground in 2019 and export volume and value rose 0.4% (to 1.0 million tonnes) and 0.7% (to USD 769.7m). This was supported by rising demand from Japan, China, Indonesia and South Korea for use in the production of food and beverage (which have specialist requirement), medicines, cosmetics, textile printing, and bioplastics. This also helped to lift export prices by 0.4% to an average of USD739/tonne.

- Cassava pellets: Exports of cassava pellets also strengthened in the year, rising by 8.3% to 0.12 million tonnes and bringing in USD3.2m (up 16.6%). This was driven by higher demand for use as input for animal feed in Japan, the main export market for this product.

- Domestic demand rose in 2019, along with the growth of the value-added downstream industries, including food processing and the production of sweeteners and ethanol. This was partly triggered by cassava industry players decision to expand to strengthen their income base. The Office of Agricultural Economics estimates that in 2019, total domestic demand for fresh cassava increased by 13.1% to 11.0 million tonnes, comprising (i) 8.2 million tonnes consumed directly by households or used as an industrial input, and (ii) 2.8 million tonnes used as an energy source[14] (Figure 17).

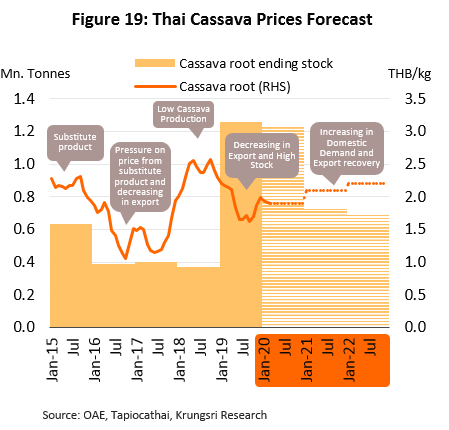

- Domestic price of fresh cassava fell because of a supply glut, to THB1.89/kilogram (down 20.6% from 2018 levels). Cassava production rose along with total cultivated area, but unfortunately 1.7 million tonnes of demand evaporated from export markets. This pushed up cassava stock, which jumped from 0.4 million tonnes at end-2018 to 1.3 million tonnes at end-2019.

Outlook

Over 2020-2022, demand for cassava is forecast to register mild growth for the following reasons.

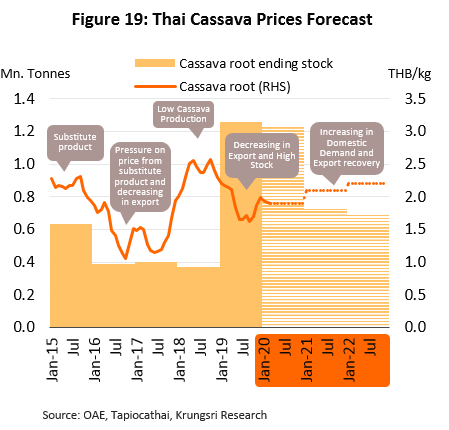

Production: Output is forecast to grow by an average of 0.5-1.0% per year, in line with the expansion of cultivated area (Figure 18). Growers will be incentivized to increase planting of cassava because of the government’s income guarantee scheme. Hence, price for fresh cassava tends to remain steady at THB 2.1-2.2/kilogram, while production cost is about THB 1.9/kilogram (Figure 19).

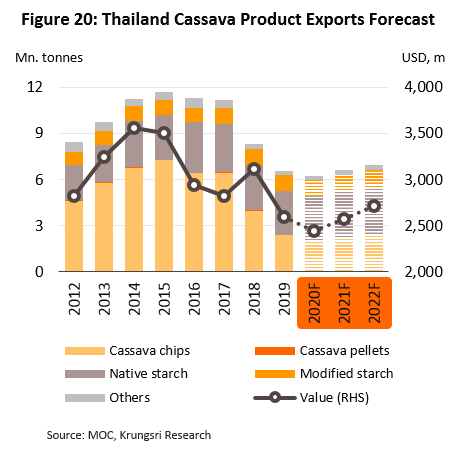

Demand: Domestic demand for cassava products is forecast to rise by 2.5-3.5% per year, because domestic demand for use in ethanol production will be particularly strong. Exports are expected to rise by 1.5-2.5% per year (Figure 20), although growth rates will vary between the individual product groups.

- Native starch: Exports are forecast to rise by 1.0-2.0% per year due to a combination of stronger demand for use in industrial applications, especially food processing and beverage production, and falling prices. Nevertheless, players will be pressured by (i) stronger competition from alternatives such as corn and wheat flour, which prices are similar cassava, and (ii) China’s decision to reduce corn stock by increasing consumption of domestically produced corn (Figure 21).

- Cassava chip: Exports of cassava chip are also expected to rise by an average of 1.0-2.0% per year as operators try to compensate for weaker sales to China by developing new markets in Vietnam, the Philippines, India and Singapore. As described earlier, there are problems with exporting to China because of: (i) the switch to using corn instead of cassava to produce animal feed; (ii) the ASF outbreak, which has reduced demand for animal feed (which uses cassava as input). It is now estimated to take at least 2-3 years to contain the epidemic and bring the pig herd back to its original size; and (iii) Chinese investment in cassava cultivation and basic processing facilities overseas15/. Domestic demand will be boosted by: (i) government policy to encourage the use of ethanol through increased consumption of E20 and E85 gasohol; and (ii) the Covid-19 pandemic, which is driving rising demand for cassava chip to produce alcohol, which may be used directly or as an ingredient in other products. Generally, cassava has benefited from global fears over the novel coronavirus pandemic, which have led to concerns about food security and stockpiling of agricultural products.

- Modified starch: Exports should rise by 2.0-3.0% per year along with the growth of downstream industries, including cosmetics, medicines and food processing.

- Cassava pellets: Exports should continue to fall due to weak demand, though this could change with a shortage in other crops that are cassava substitutes.

Operators: Producers of cassava chip and native starch will encounter stiff price competition in the coming period. This will suppress revenues and margins (Figure 22 and 23). However, competition will ease in the modified starch segment, and would push up revenues and margins. In addition, rising investment in related industries (e.g. ethanol refineries and bioenergy factories) and introducing new value-added products will help to build alternative income streams and reduce the risk of being adversely affected by fluctuations in export markets. Also, the fact that some operators are able to generate their own electricity will also help to cut production costs. However, producers of cassava pellets are likely to continue to face ongoing problems with depressed demand in export markets.

Major factors influencing the market in the coming period

Positive factors

- Short-term (affecting the market in 2020-2021): This will stem from the necessity to curb the spread of Covid-19. It will increase demand for cassava products to (i) produce alcohol for use directly or as a component in other products, and (ii) meet increased demand for food products amid rising fears over food security and households stocking up on food.

- Long-term (from 2022 onwards): These include government support for alternative energy, which will continue to drive up demand for cassava for use in ethanol production.

Challenges

- Short-term: These comprise: (i) uncertainty over production, which are determined by (a) prices, (b) climate (Figure 24), and (c) risk of outbreak of cassava mosaic disease; and (ii) drop in global demand, especially due to (a) China’s decision to replace imported cassava with corn, and (b) falling demand for animal feed following the ASF epidemic.

- Long-term: These include: (i) competition for supply of fresh cassava to use in industrial applications, especially in high value-added biotech industries and other sectors that enjoy government support; (ii) heavy dependence on the Chinese market, which makes Thai operators highly sensitive to changes in China’s government policies; and (iii) rising competition in the global market, especially from Vietnam and Cambodia, which could pressure exports and margins.

Proposed bill on profit-sharing in the cassava industry

- In line with Article 77 of the Constitution, the government is gathering opinions on the proposed act to regulate the cassava industry. This process started on December 27, 2019. If the bill is enacted, it will likely affect players’ margins.

Programs and measures affecting the cassava industry, 2019-2020

1) Guaranteed income for cassava growers, 2019-2020: A cabinet resolution passed on November 12, 2019, approved an allocation of THB9.67bn to support the income of cassava farmers. About 0.52 million people are eligible for this aid, details of which are as follows:

- Access, prices and limits of the scheme: The program is open to farmers who plant cassava with 25% starch content in 2019 and 2020, for which it sets a target price of THB2.50/kilogram. The relief is limited to 100 tonnes of cassava per household.

- Claiming top-up payments on the difference between market and target cassava prices: Registered cassava growers who record the date of their harvest with the Department of Agriculture Extension (under the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives) are eligible.

- Payment conditions: Assistance is limited to 100 tons of cassava per household, and applications may be made only once for each location.

- Making top-up payments: The Bank for Agriculture and Agricultural Cooperatives will transfer funds equal to the difference between the target price and the market price (the central reference price) directly to farmers’ accounts.

- Duration of the scheme: (i) Farmers have been able to register for the scheme since October 1, 2018. (ii) The scheme applies to the growing season specified in each applicant’s registration. The government made the first payment on December 1, 2019, and additional payments are made on the first of the month for the following 12 months. Farmers who harvested before December 1, 2019 were able to claim their payments on that date. (iii) The program will run from October 1, 2019 to December 31, 2020.

2) Improving the efficiency of cassava growing: The Bank for Agriculture and Agricultural Cooperatives has been tasked with allocating credit to be used to invest in the development of the cassava growing industry, and to reduce growers’ costs through the application of appropriate technology. To this end, 5,000 loans of up to THB230,000 each have been made available (with a total value of THB1.15bn) at an annual interest rate of 3.875%, to be repaid within 24 months.

3) Providing credit to cassava buyers who are adding value to cassava products: The Bank for Agriculture and Agricultural Cooperatives is also offering loans to farming groups that are active in cassava cultivation or who are raising livestock. The caveat is that the funds would be used as working capital to buy fresh cassava or cassava chip that will be sold or processed at a later date. This plan is aimed at soaking up excess supply of cassava that is currently weighing on the market. The total allocation is THB 1.5bn, and the loans are repayable over 12 months at an annual interest rate of 1%.

4) Promoting greater domestic cassava consumption: This program promotes the development of cassava-based bio-plastics and greater use of cassava in the food processing industry.

5) Increasing sales channels through which cassava products are distributed: Efforts have been made to increase the distribution of alcohol that is made from cassava and bagasse, for which markets are limited. There is strong promotion for ethanol but during 2017-2019, this can absorb only 2.8 million tonnes of cassava per year. To increase the use of cassava and other crops in the production of alcohol and to allow ethanol producers to supply their products to industrial users (in addition to being used as fuel), the Liquor Act (B.E. 2493) will need to be revised.

6) Ensuring fair trade in cassava: This includes putting in place measures to check the quality of cassava, to subtract the weight of impurities from sold goods, to ensure that cassava chip and starch processing factories use machinery to remove impurities, and to make sure that purchase prices are displayed.

7) Managing imports and exports: The Department of Foreign Trade should put in place measures to ensure the quality of goods meet the established standards and to impose strict penalties on those who violate the rules.

Activities of the Joint Standing Committee on Commerce, Industry and Banking (JSCCIB) in relation to the cassava industry

1) Declaring cassava holdings: Business operators, owners and individuals who have monthly cassava holdings of more than 15 tonnes are required to report their purchases (the type of goods bought and the price paid), the distribution prices, their current holdings, the quantities bought, distributed, received, used and remaining, the storage location, and to keep full inventory records.

2) Transportation of cassava: The transportation of loads of cassava or cassava chip weighing over 10 tonnes into or out of 12 specified provinces is prohibited without the permission of the chair of that province’s JSCCIB or of an authorized representative.

3) Regulations for making purchases of cassava and displaying prices for starch content: If operators of collection yards, starch processors and ethanol distillers discover the cassava sold has a lower starch content than specified, they are permitted to reduce their purchase price by up to THB0.05/kilogram/1% of differential starch content. Conversely, if they discover that the cassava has a starch content that is higher than that specified, they may increase their purchase price by the same proportion.

4) Adding cassava root (for replanting) to the list of controlled goods: To stop the spread of cassava mosaic disease, it is now prohibited to take cassava into and out of specified areas without prior permission.

Krungsri Research’s view

Manufacturers of basic cassava products are likely to encounter strong price competition from alternative crops, and run the risk of becoming loss-making. However, modified starch is a high-value-added product, so manufacturers will be able to maintain profitability in the coming period.

- Producers of cassava pellet: Sluggish demand in export markets means that manufacturers are exposed to risk of losses.

- Producers of cassava chip: Earning will fall, pressured by shrinking Chinese demand and increasing competition from alternative crops in the global market. Profits may also be dragged down by rising competition for access to raw materials from industrial consumers. However, demand for cassava chip for use in ethanol production, another high-value-added product that has growth potential driven by the anticipated increase in consumption of biofuels, could offset part of the losses.

- Producers of native starch: Earning will remain flat because although domestic consumption will rise with greater demand from the food and drinks industry, this will be balanced by weak sales to China and competition from starch produced from other crops.

- Producers of modified starch: Earning should jump following expansion into downstream industries in Asia, including cosmetics, food and medicine, coupled with plans to penetrate new export markets.

- Traders of cassava products: Earning should be stable. Demand for cassava from the domestic and export markets will grow steadily, which will allow operators to preserve their margins.

- Cassava growers: Risk of buyers pushing down prices for fresh cassava. But as production costs remain stable, they will need to operate with narrower margins. However, on a more positive note, farmers are being supported by the government in the form of income guarantee, low-interest loans, and measures to absorb excess supply. And in the coming period, industry demand for fresh cassava is expected to rise steadily.

[1] n Asia, cassava is used principally as an input to downstream industries, rather than for direct human consumption. But many countries have been moving to strengthen their food security, especially India, Indonesia and the Philippines, where cassava has been promoted as an alternative to rice. In Latin America, governments have pushed the commercial cultivation of cassava mainly for use as an input to industry.

[2] In 2018, average global consumption of cassava came to around 20 kg./person/year (source: Office of Agricultural Economics).

[3] Data from the Office of Agricultural Economics. Cassava can be grown in poor soils and is drought tolerant so it can be planted year round. In Thailand, however, cassava is usually grown between March and May, and harvested from December to March in the following year.

[4]This includes many cassava processing factories that output different products, including cassava pellets, cassava chips, starch, cassava pulp and other goods (source: Department of Business Development, Department of Industrial Works and the Thai Tapioca Products Factory Association)

[5] Modified starch is made from native starch, which has its physical and chemical properties altered through the application of heat, enzymes and/or chemicals. This gives the modified starch particularly desirable qualities that then make it more useful in industrial applications, such as making its viscosity less variable, increasing its stability at a wider range of temperatures, and altering its acidity and shear strength.

[6] Equivalent to 3.0 million tonnes of fresh cassava root.

[7] Producing 1 liter of ethanol requires 6.25 kilograms of fresh cassava root.

[8] Producing 1 kilogram of chips or pellets requires 2.42 kilograms of fresh cassava root.

[9] Producing 1 kilogram of cassava starch requires 4.20 kilograms of fresh cassava root.

[10] To produce a nutrient profile similar to corn, animal feed is produced by mixing cassava chip and soy pulp at a ratio of 87:13.

[11] The reform of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) that was carried out in 2005 required member states to source crops from within the EU rather than import cassava pellets from Thailand, and since then, Thai producers have instead switched to manufacturing cassava chip for export.

[12] The Chinese Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs (MARA) confirmed that the first ASF outbreak occurred in Liaoning Province on August 3, 2018 (Source: FAO).

[13] In 2018, cassava production costs averaged THB 1.85/kilogram.

[14] Source: Department of Alternative Energy Development and Efficiency, Ministry of Finance.

[15] China has been investing in agricultural production in many countries in the region including Cambodia (in rubber, acacia, cassava and sugarcane), Lao PDR (mostly in the north, near the Chinese border, and in rubber, sugarcane, corn (for animal feed), banana, cassava, teak and eucalyptus) and Myanmar (rubber, cassava, sugarcane, banana and watermelon) (source: Chinese Agriculture in Southeast Asia: Investment, Aid and Trade in Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar).

.webp.aspx)