Private hospital business is expected to enjoy average annual growth of 10-13% from 2019 to 2021. Business expansion will be underpinned by structural changes in Thai demographics, including the aging society, continuing urbanization, and the ongoing growth of the middle classes. In addition, increasing health-awareness trend globally with personal health and wellness will also help to support sectoral growth.

Players will likely increase the scope of their investments through this period in order to offer a more comprehensive set of fully-integrated services and so better meet the widening range of consumer needs. In this environment, private hospitals that are part of extended commercial networks will enjoy advantages in terms of their costs, human resources, and access to consumers of healthcare services. Stand-alone hospitals will, on the other hand, need to increase their competitiveness in the face of a number of rising challenges, including the entrance of new operators to the sector.

Overview

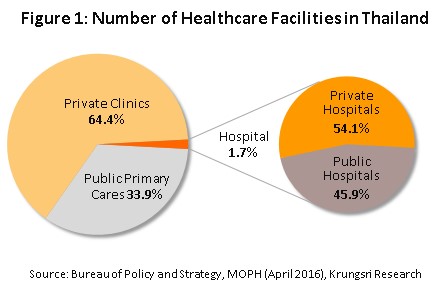

At present, Thailand is home to a total of 38,512 sites providing some form of healthcare provision[1] 34.7% of these are state-funded healthcare providers (e.g. public health centers, district public health offices, and community and general hospitals), while the remaining 65.3% are private sector ventures (i.e. private clinics and hospitals).

Divided according to size and the range of medical services that they offer, 98.3% are classified as primary healthcare providers2/ (9,800 public health and district health promotion centers and approximately 24,800 private clinics). The remainder comprises 641 secondary and tertiary healthcare providers, split between 294 (or 45.9%) hospitals under the management of the government, the Ministry of Public Health, local administrative bodies, state enterprises or the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration. The remaining 347 hospitals (54.1%) are in the private sector (Figure 1)

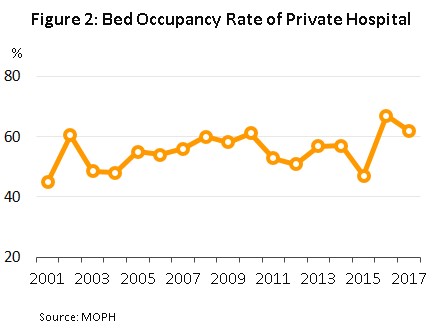

However, although state hospitals may be found across the country, their ability to serve patients is limited in some locations, as can be seen from the following: (i) The bed occupancy rate[3] is high and in some areas is close to or over 100%. At present, the occupancy rate stands at 103% in Satun, 98% in Loei, 96% in Phuket, Mukdahan and Surat Thani, and 94% in Udon Thani and Pathum Thani, so it appears that at least in some areas, the supply of government hospital beds is insufficient to meet demand; and (ii) Outpatients typically face long waits before being seen by a healthcare professional. The failure of government health services to fully meet demand has thus presented an opportunity to private healthcare providers, which typically emphasize the speed and convenience of their services. The result of this situation is that middle class consumers who have sufficient spending power are increasingly turning to the use of hospitals in the private sector, despite these services carrying a higher price tag than does accessing equivalent services in a government hospitals.

A survey of hospitals and private healthcare providers[4] carried out in 2016 revealed that in that year, Thailand was home to 347 private hospitals, up from the 321 recorded in 2012. 116 of these were in the central region of Thailand (33.4% of all private hospitals), 105 were in Bangkok (30.3%), 52 were in the north (15%), 40 the northeast (11.5%) and 34 the south (9.8%). These hospitals housed a total of approximately 41,000 beds, an increase from the 35,000 recorded in 2012 (Figure 3).

Private hospitals may be divided into three subgroups according to the number of patient beds that they contain; this is a useful proxy for evaluating the range of medical services that each offer (Figure 4).

- Large hospitals (more than 250 beds): Bangkok and the central region of Thailand have the highest concentration of mid- to upper-income consumers and so some 90% of large hospitals are located in these areas. Currently, there are 21 large private hospitals in Thailand, and although this is around only 6% of all private hospitals, these have a combined capacity of 11,772 beds, or approximately 28.9% of all private hospital beds.

- Medium hospitals (31-250 beds): There are 243 hospitals (70.0% of the total) providing 27,232 bed spaces (also 66.9% of the total)

- Small hospitals (1-30 beds): There are 83 small hospitals in Thailand (23.9% of the total) offering 1,714 beds (4.2% of the total).

Private hospitals have been helped by their tax-exempt status and by other government policies aimed at supporting these businesses. In addition, business expansion has been driven by rising demand which has been especially from patients in neighboring countries following the opening of the Asian Economic Community in 2015, though health and wellness tourism from further afield has also steadily increased. These factors have helped to stimulate a marked uptick in investment by players in private healthcare and this in turn has caused a transformation of the sector; large, dynamic businesses have engaged in mergers and acquisitions, opened new hospitals in Bangkok and important regional centers, and bought into other private hospitals as investments and to extend their commercial networks. This has then led to the establishment of a number of new, large commercial groups that operate private hospitals, including the Bangkok Hospital Group, the Thonburi Healthcare Group and the Bangkok Chain Hospital (the Kasemrad Hospital group). These mergers have increased competitiveness, and groups are now clearly targeted at particular customers, while in light of these changes to the structure of the market, mid- and small-sized operators have had to adjust their operations by specializing to target more niche markets.

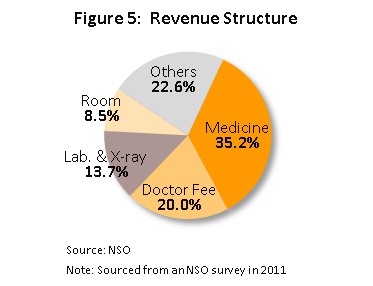

The income structure of private hospitals is such that the largest source of income (35.2%) comes from the sale of medicines and pharmaceuticals. Second in importance is medical treatments/services (20.0%), followed by laboratory tests and x-rays (13.7%), accommodation fees (8.5%), and other income (22.6%) (Figure 5).

A survey of private hospitals revealed that in 2016, there were a total of 61.6 million patients to private hospitals in Thailand. 58.8 million of these (95.5% of the total) were for out-patient services and 2.8 million (4.5%) were for in-patient treatment. The greatest share of these were made in Bangkok, with 32.2 million patients (52.2% of the total), followed by the central region (29.1%), the north (8.0%), the northeast (5.4%) and the south (5.3%). 93.1% of all patients were made by Thai nationals, and only 6.9% were made by non-Thais (Figure 6), the latter group being split between expatriate patients (roughly 20%) on the one hand and general and medical tourists (approximately 80%) on the other[5]. In terms of the origins of non-Thai patients, Myanmar, Japan, the Middle East and Europe were the most important.

The size of a hospital is an important factor in determining its competitiveness and profitability. Large hospitals tend to be on a stronger financial footing and will typically be part of a more extended business network, which then enables them to take advantage of economies of scale since individual units within a commercial group will be able to pool resources by, for example, making joint purchases of medical supplies and equipment. In addition, because they provide services to a wide range of customer groups and so see fewer fluctuations in income, large operators can absorb pressures arising from a changing business environment better than can their small- and medium-sized competitors. Nevertheless, for all operators, the healthcare sector offers security and relatively low levels of risk since healthcare is a necessity and so economic slowdowns affect these businesses less than they do players in other sectors. This also means that operators are more able to pass on rising costs to consumers, and so for many years now, private hospitals registered on the stock exchange have seen income and profits rise steadily.

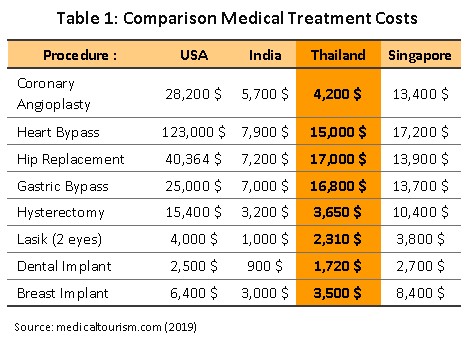

The healthcare sector has been the beneficiary of government policy that stretches back to 2003 to promote Thailand as a ‘medical hub’, and this has in fact led to the steady growth of medical tourism in the country. In many Thai private sector hospitals, the quality of service and treatments matches global requirements and so these institutions are now recognized as meeting international standards, one of the goals of the policy. At the same time, when compared to other countries that offer equivalent levels of care, the cost of care in Thailand is relatively low (Table 1), while Thailand also benefits as a medical hub from its many natural attractions, making it a suitable destination for those recuperating from illness or treatment. At present, the Joint Commission International (JCI) accredits 66 Thai medical institutes as meeting international standards (Figure 7), which is a greater number than in regional competitors such as India (38), Singapore (22), and Malaysia (13). In 2017, the International Healthcare Research Center (IHRC) placed the Thai medical tourism segment sixth in its world rankings, behind India, Colombia, Mexico, Canada and the Dominican Republic, while acknowledging that Thailand is the market leader in Asia, with a 38% market share of the Asian medical tourism market. At the same time, the Medical Travel Quality Alliance has declared that one of Thailand’s medical facilities is among the five best medical tourism destinations in the world, with the other four sites located in Germany, Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey.

The sector is also helped by the fact that the government has decided to assist it as part of the project to further develop Thailand as an international medical hub over the period 2017-2026. Measures in pursuit of this include: (i) extending the permitted period of stay for visitors traveling to Thailand for medical treatment from China and the CLMV nations to 90 days from 30 days and allowing up to 4 family members to accompany travelers bound for Thai hospitals; (ii) extending long stay visas from 1 to 10 years for individuals from 14 specified nations6/; and (iii) assembling a special dental and health-check package for international travelers. These moves will all help Thai private sector hospitals expand their market to include greater numbers of international patients, a group that has higher spending power and which tends to spend more on healthcare than its domestic counterpart. The income for private hospitals is therefore growing solidly, and healthy profit rates are being maintained.

Access to medical services and public healthcare in Thailand

Access to medical services and public healthcare is a fundamental necessity of life, and the state has an important role to play in establishing a healthcare system and then facilitating access to it through public welfare. In light of this, the World Health Organization (WHO) has stated that Thailand’s universal health coverage (UHC) is one of the best models available for low-cost healthcare systems[7], even though per capita income in Thailand is relatively low compared to other countries that have put in place UHC systems.

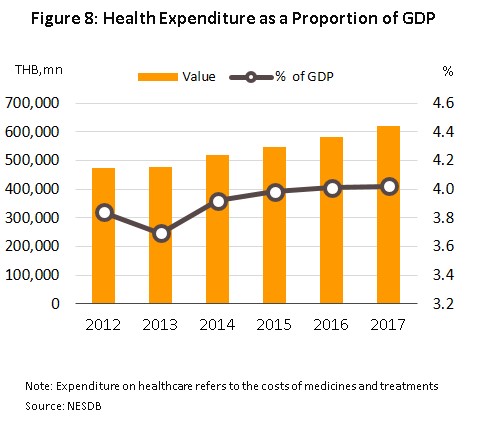

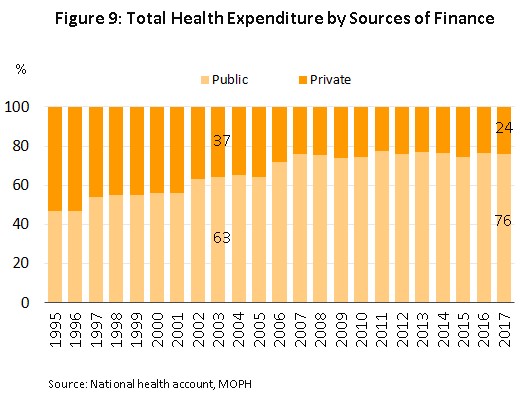

Thailand instituted its system of universal healthcare in 2002 with the enacting of the National Health Security Act and as of the most recent data, 66.05 million people, or 99.94% of those with a right to healthcare, are now covered (Figure 8). Three funds are available through which Thai citizens are able to access this care: (i) the Universal Coverage Scheme (UCS)[8]; (ii) the Social Security Scheme (SSS)[9]; and (iii) the Civil Servants Medical Benefit Scheme (CSMBS)[10]. The result of introducing Thailand’s UHC has been to increase spending on healthcare from 3.8% of GDP in 2002 to 4.0% in 2017 (Figure 9) and data from 2014 indicate that 77% of this expenditure originates from public sources (Figure 10) while private sector contributions to the total are declining. At the same time, though, the proportion of Thai households experiencing ‘catastrophic health expenditure’[11] has declined from 5.7% of all households in 2003 to 2.3% in 2017.

Situation

Operators of private sector hospitals are engaged in the twin processes of raising the quality of their services to meet international standards and of ongoing investment to increase market share and maintain income growth over the long term. In pursuit of this a number of strategies have been seen in the sector, including the expansion of premises offering healthcare services and related facilities, investment in treatment centers for specialist or complex conditions,

while larger, more forward-looking hospital operations have extended their commercial networks through enlarging existing hospital sites or opening new ones in regional centers, and, to meet demand from tourists and patients in neighboring countries, in important tourist destinations and border provinces. In addition,

players have engaged in mergers and acquisitions, buying well-performing hospitals outright (e.g. Bangkok Hospital’s purchase of Muangraj Hospital and Mayo Poly Clinic, and Bangpakok Hospital’s acquisition of Sotharavet and Piyavate hospitals),

acquiring stock in other profitable hospitals (e.g. Bangkok Hospital’s holding of shares in Bumrungrad Hospital), or

joining in commercial partnerships with other hospitals, both domestic and international to provide shared care for patients, or with non-hospitals to expand operators’ customer bases. Beyond this,

players have also moved into related businesses, such as pharmaceuticals and medical supplies, food supplements, cosmetics, and operating beauty clinics and care facilities for the elderly.

Small- and medium-sized hospitals that are ‘stand-alone’ operations (i.e. that are not part of an extended commercial network)

have had to adjust to changing circumstances by, for example, specializing in the services that they offer or by securing their income by focusing their efforts on offering services to patients in receipt of government-funded healthcare. Private hospitals are thus competing in a market that is as fiercely competitive as any other.

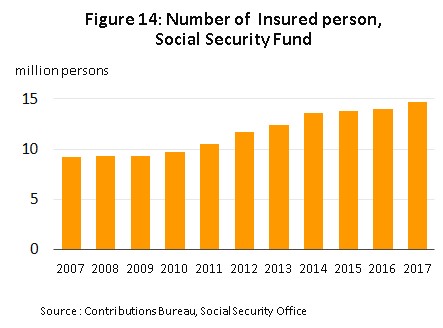

However, despite this generally positive assessment, between 2013 and 2016, private hospitals were nevertheless affected by the sluggishness of the domestic economy and in this period, middle-income consumers, the primary target of private hospitals, exhibited greater care when making spending decisions with the result that the number of patient-visits dropped significantly (Figures 11 and 12). Some customers cut back on spending by sourcing medicines themselves, accessing treatment under an alternative government scheme, or visiting a cheaper private clinic, while others postponed treatment of less urgent or less serious conditions. In response to this, large hospitals have adjusted their business strategies, focusing more on customers who would otherwise take advantage of public healthcare schemes by using more aggressive pricing strategies and by offering targeted ‘care packages’ (Figure 13 and 14). This, though, has increased risk for small- to medium-sized hospitals, which have lost a part of their customer base as a consequence of the market realignment of large players.

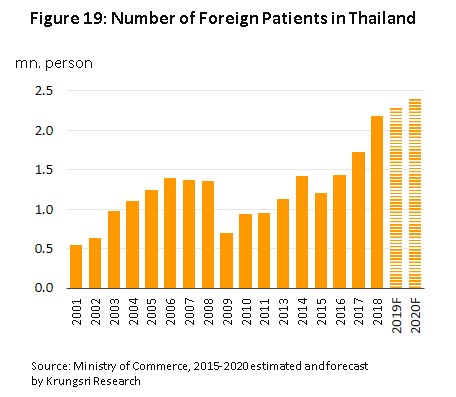

Unfortunately, private Thai hospitals that have targeted foreign customers have also been affected by slowing economies abroad, especially for those hospitals which treat customers from the Middle East, where several years of low oil prices have forced cuts to budgets for medical expenses. Thus, the United Arab Emirates has reduced official contributions to treatments made abroad from 90% to 50% of costs, while Qatar and Kuwait have invested in the construction of their own new, modern facilities. Demand from Middle Eastern customers has therefore softened and so hospitals have had to look to new markets to take up the slack, with higher-income patients from the CLMV region, China and Russia being particularly promising. Meanwhile, medical tourism has continued to expand. The Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT) states that an average of 2 million visits of medical tourists have been recorded annually, with this hitting 2.3-2.4 million in some years[12]. The majority of these arrivals were for health checks, surgery, dental work and anti-aging medicine. Overall, this shift in the customer base has meant that through this period, the number of foreign patients and revenues have not fallen substantially, and for some operators, numbers have even improved.

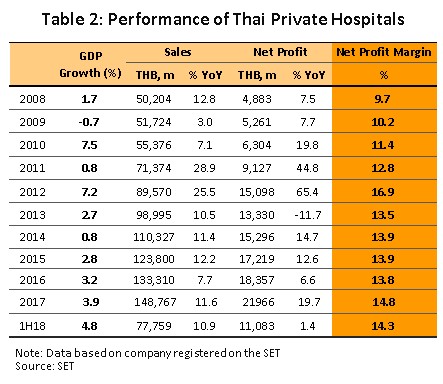

In 2017, income for hospital operators registered on the Thai stock exchange jumped by 11.6% YoY on rising purchasing power, itself lifted by economic growth of 3.9% YoY. In addition, hospital income was boosted by: (i) the spread of seasonal illnesses, including influenza and dengue fever; (ii) increases to the payments made to hospitals by the Social Security Scheme, combined with a rise in the number of patients covered by the scheme (though this only affected the 55.5% of private hospitals that take Social Security patients); and (iii) the spread of medical tourism and the improving state of the global economy, which led to a rise in the number of foreign tourists coming to Thailand for treatment, and thus KPMG[13] estimates the number of foreign patients at 2.4-3.3 million in 2017. As a consequence of these positive factors, in the first half of 2018, income for private hospitals rose by 10.9% YoY and operators reported average net profit margins of 14.3%, slightly above the average of 14.1% for the period 2011-2017 (Table 2).

Industry Outlook

For the three years between 2019 and 2021, hospital operators should see steady growth in their business. Large hospitals that are part of an extended commercial group will be able to exploit their advantages in terms of costs, personnel and access to a wide range of customer groups, both domestic and international. However, with the exception of those that specialize, either in terms of their customer base or the treatments which they offer, mid-sized and small hospitals that are ‘stand-alone’ operations (i.e. that are not part of a commercial group) will likely face greater challenges because these players are dependent on the domestic market. Nevertheless, small and medium hospitals with greater business potential may be able to access financing through the stock market[14] and these funds would then be available to upgrade and expand operations or for use as working capital. Opportunities also exist to enter into partnership with large players by referring on patients to them, and by engaging in these types of commercial alliances, smaller operators will be able to increase their competitiveness and meet the challenges posed by the dominance in the sector of major commercial groups. Krungsri Research thus anticipates that in this period, revenue from hospital businesses registered on the stock market would grow by an average of 10-13% per annum.

Structural changes that will support business growth include the following:

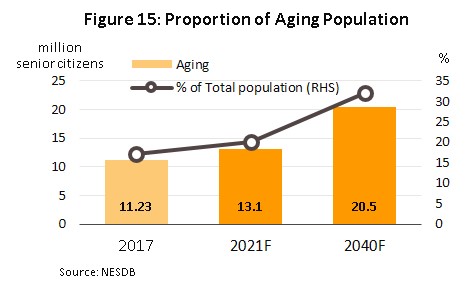

- The transition to an aging society will support rising demand for complex and technology-intensive medical interventions. The Office of the National Economic and Social Development Board forecasts that in Thailand, the number of individuals aged over 60 will rise from 11.2 million in 2017 to 13.1 million by 2021 (Figure 15), and typically 60% of the elderly have health problems[15], while the Ministry of Public Health estimates that spending on healthcare for the elderly is expected to rise from THB 63 bn in 2010 (2.1% of GDP) to THB 228 bn in 2022 (2.8% of GDP) (source: the 12th National Health Development Plan, 2017-2021)

- Growth in the number of middle-class consumers with higher spending power[16] will also help to increase demand for the services offered by private hospitals. It is forecast that the proportion of the Thai population classified as middle-class will rise to 41% by 2020, up from 36% in 2015. This societal shift is also being seen in other countries in the ASEAN zone (Figure 16) and taken together this represents a significant opportunity for Thai private sector healthcare providers.

- Urbanization is continuing in Thailand and the United Nations forecasts that the Thai urbanization rate will in fact rise from 50.4% in 2015 to 60.4% in 2025 (Figure 17). This, combined with government policy to invest in national infrastructure and to establish special economic zones and the Eastern Economic Corridor, will increase opportunities for players to expand the provision of medical services and to meet demand from patients in the provinces, including non-Thais who have come to work in the country.

In addition to these structural factors, growth in income for operators of private hospitals will also come from the following:

- Rates of illness and death as a result of non-communicable diseases (NCDs)[17] such as cancer, stroke, heart disease, pneumonia and diabetes are tending to rise in the Thai population (Figure 18). Unhealthy lifestyle choices are prevalent in the general population and data from 2014 show that the proportion of over-15s who smoke or drink alcohol stands at 20.7% and 32.3%, respectively[18], while average consumption of sugar is five-times the recommended level. Looking forward, this will underpin higher demand for medical services.

- Operators plan to expand their customer base by increasing investment in a number of areas and widening the range of services that they offer. This will include opening new branches (e.g. Bangkok Hospital hopes to have 50 branches operating in 2021, up from 45 in 2018, while Bumrungrad is opening a new branch on Phetburi Tat Mai Road in Bangkok that is expected to be completed in 2020), entering into partnerships with other hospitals to increase treatment options (e.g. the decision by Praram 9 hospital to transfer patients with kidney conditions to one of nine favored hospitals across the country), or building competitiveness by emphasizing an operator’s particular strengths. The Latter might involve introducing the use of high-tech treatments, meeting customer needs for personal treatment from experts by modifying operations to become a center of excellence, or investing in technology to become a ‘digital hospital’, as Bamrungrad and Praram 9 hospitals have done. Some other operations are focusing instead more on overseas customers, shifting away from an earlier concern with the domestic market. Beyond this, operators have moved into non-hospital business by developing their whole supply chain such as beauty and old-age care centers, operating pharmacies, offering laboratory services, and producing pharmaceuticals, food supplements, medical foods, and beauty products. These products and services will appeal to a broad cross-section of consumers, this will also assist in securing long-term income growth.

- Moves to expand the customer base will also involve looking more closely at foreign markets, and particularly at more promising segments, such as the markets in the CLMV nations, China, Russia and Africa, a move that will also reduce the pressure of relying excessively on any one market. From the point of view of hospital operators, these countries have the advantage of lacking sufficient domestic healthcare infrastructure to meet demand and so represent an open opportunity for expansion. This is particularly the case with the Chinese market, where couples are keen to use artificial insemination to have a second child, and hospitals that have expertise in this area (such as Ekachai and Piyavate hospitals) have been able to open centers for the treatment of fertility problems and so meet demand from China. It is expected that many other hospitals will rush to adjust their operations in order to do likewise. As a consequence of these moves, the number of foreign patients coming to Thailand for treatment will tend to rise (Figure 19), while trends in the coming period also point toward an increase in the number of operations abroad that are managed by Thai private hospitals. This may take the form of players building their own hospitals, investing in local operations, or establishing offices for agents to send patients on to Thai hospitals. Recent examples include the Welly Hospital in China, which was opened at the end of 2017 and which is a joint venture between Thonburi 2 Hospital and a local Chinese business, and the Ar Yu International Hospital in Myanmar (opened in 2018).Players in the private hospital sector will also face more intense competition both domestically and internationally.

- Support from the government for private healthcare is taking a number of forms.

- The move to establish Thailand as an international medical hub is in line with the growing global market for health and wellness tourism. “The Global Wellness Tourism Economy Report 2013-2015” states that worldwide, health and wellness tourism was worth USD 639 bn in 2017 and that the sector is expected to grow at an annual rate of 7% through to 2022. The Asia-Pacific market is valued at USD 136.7 bn, with over 2.5 million health tourists recorded in the region annually, while in terms of its market share, Thailand is in fourth place in Asia. Services in demand from health and wellness tourists include dental care, health checks, cosmetic surgery and anti-aging treatments, though increasing interest in and concern with personal health is pushing private hospitals to spread their activities into a wider range of services. Thus, the Bangkok Hospital Group has opened the BDMS Wellness Clinic, Medical City has been opened by the Thonburi Healthcare Group and Bangpakok, Kluaynamthai and Yanhee hospitals have all established care facilities for the elderly. The Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT) and private sector collaborate to promote Thailand to become a ‘fertility center’ to help place Thailand on the map as a hub for fertility wellness tourism, and the support of policy aimed at strengthening health tourism will help to maintain the growth of the market over the longer term (Table 3).

- Listing the medical sector among the government’s ten targeted industries, in particular for investment in the EEC which carries with it special privileges such as tax breaks, will help to encourage investors to put money into the sector. This will include establishing research facilities, manufacturing pharmaceuticals, and engaging in medical innovation. Private hospitals should then benefit from this by seeing their costs of production fall, which will in turn help to lift their competitiveness relative to overseas competitors.

However, challenges to the sector exist, and these include the following:

- The healthcare sector is suffering from a labor shortage. The World Health Organization (WHO) has declared that there should be at least 2.8 doctors and nurses per 1,000 head of population but at present, Thailand has a ratio of only 0.4:1,000, lower than that of its main regional competitors of Singapore (1.92:1,000) and Malaysia (1.2:1,000). Expansion by private sector hospitals will thus tend to feed increasing competition for staff and this will then lead to higher business costs.

- Official regulations, such as the possibility of including the costs of pharmaceuticals, medical supplies and service fees in government price controls placed on the medical sector may have an impact on operators’ room to increase charges and through this, on their future turnover. This is likely to be particularly significant for stand-alone mid- and small-sized hospitals.

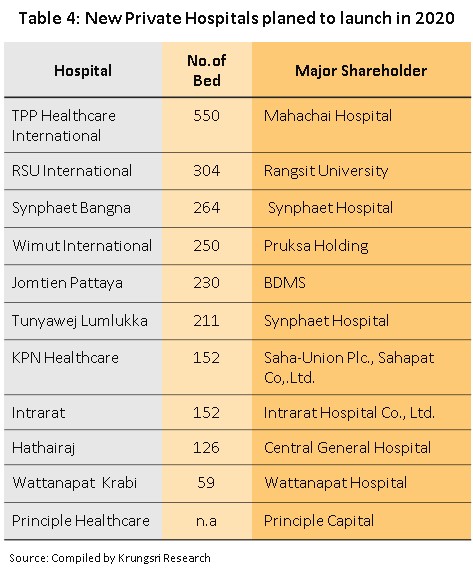

- Operators also have the prospect of stiff competition to look forward to, with this coming from both competitors at home and abroad. In the case of the former, in addition to facing challenges from existing providers of healthcare services that are in the process of speeding up their investments, players will also have to overcome obstacles arising from the entry into the market of businesses from outside the healthcare sector that are attracted by the possibility of securing low risk, secure, long-term returns, though these moves are also in step with shifts in consumer preferences that place greater importance on personal health (Table 4). Foreign investors are also attracted to the sector and this is especially the case for Chinese businesses, which are keen to meet demand from Chinese patients for the treatment of infertility problems in Thai-run clinics. The outcome of these developments has been to create a sharp expansion in the supply of private hospital beds. The total number of these is thus expected to rise by at least 1,000 beds by 2021 from the 2018 total of 40,000 and this will naturally lead to increasing competition between private hospitals, with this likely to occur on both pricing and the range of services offered. In addition to this, competition will also come from government-run hospitals that are developing services that mirror those available in the private sector. Piyamaharajkarun Hospital, part of the Siriraj Hospital network, and the Somdech Phra Debaratana Medical Center at Ramathibodi Hospital are examples of public hospitals that have followed this path, and operations such as these will benefit from their reputation in the excellence of their staff and their adoption of high-tech treatments. As regards foreign competitors, many Asian countries have followed a similar path to Thailand in establishing medical hubs and these also tend to target the same customer groups. Singapore, Malaysia, India and China all fall into this category, with China having declared Hainan as a medical tourism pilot zone as a way of attracting domestic patients who would otherwise use medical services abroad. Recently, the Singaporean operator Parkway Pantai announced that it will be building a 250-bed hospital, its first, in Myanmar for opening in 2020 and Middle Eastern countries, which supply many patients to the leading private hospitals in Thailand, are also opening their own hospitals. At a cost of THB 23 bn, Qatar opened Medical City (similar in size to Bamrungrad Hospital and equipped with 559 beds) at the end of 2017. Likewise, costing THB 35 bn, Kuwait has already opened the 1,168-bed Hospital Complex, while the United Arab Emirates (UAE) has adjusted its health insurance policy and is now encouraging those requiring medical care to do so in the UAE instead of traveling abroad. This increasing competition will tend to place a limit on the profitability and growth of private hospitals and to increase risk for stand-alone small- and medium-sized operators, which are likely to lose customers and market share and which will therefore tend to protect their position by entering into commercial partnerships with other players in the sector. Beyond this, competition is also likely to increase from operators in the ASEAN zone, such as the Malaysian KPJ Healthcare Berhad, which has been active in Indonesia; the challenge of operating in this sector requires players to face the test of rising competition and to seize opportunities as they arise in the future.

Krungsri Research’s view

It is forecast that large private hospitals will see solid revenue growth but small- and medium-sized hospitals, along with general clinics, will be at risk of closure, of being bought out by foreign investors, or of being acquired by large domestic operators, which are putting in place strategies for horizontal and vertical business expansion.

- Large and specialist hospitals, specialist diagnostic and treatment centers, and medical centers offering care and residential facilities for the elderly: Players in these areas will see ongoing business expansion as a result of their ability to offer services with a high level of expertise and because demand from their customers, who are in middle- to upper-income groups, will tend to rise. In addition, demand for specialist services will likely increase in all age groups, though especially so for the elderly, who will need treatment for chronic and complex conditions that require specialist, high-tech interventions. Moreover, the ability to offer high-quality services at a price that is lower than those charged by competitors in other countries should help to attract foreign customers, these comprising the main customer base for some hospitals. Plans to expand existing operations and to open new branches will also help operators reach out to new customers and this too will help to secure income growth.

- Small and medium private hospitals (especially stand-alone hospital): Operators in this group are at risk of being bought or acquired through mergers and acquisitions because many smaller hospitals operate on a weak financial basis and this means that they lack the capital necessary to invest in equipment or in medical staff with high levels of expertise. These hospitals are thus threatened by large private operators and by state hospitals, since the latter are expanding their customer base to include those groups currently targeted by small- and medium-sized hospitals. However, for those operations that provide healthcare for social security-funded patients, the effect of these changes on their business should be balanced by the increases to per patient social security payments made in 2018.

- Private clinics: These will face difficulties in expanding their customer base because: (i) the government social security system encourages patients to access healthcare services in government and private sector hospitals; (ii) operators of private hospitals have modified their business model and are increasingly competing directly by reaching out to poorer customers through the offering of services via channels other than traditional hospitals, including through community clinics, stand-alone specialist clinics, and smaller clinics in regional centers, the provinces and border regions; and (iii) substitutes for services provided by clinics exist in the form of sourcing modern or traditional medicines oneself or of using alternative medicines.

[1] Data released on April 4, 2017 by the Bureau of Policy and Strategy, Office of the Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Public Health.

[2] The criteria for the classification is based on a geographic information system (GIS).

- Primary care providers include public health centers, municipal centers, community health centers, community hospitals, general hospitals, and other units. These may be in either the private or public sector.

- Secondary care is split between: (i) basic secondary care, which comprises community hospitals, general hospitals, and state and private medical units that have in-patient facilities to treat general conditions; (ii) mid-level secondary care, which comprises medical institutes that offer common specialist treatments; and (iii) upper-level secondary care, which comprises medical institutes that offer less common specialist treatments.

- Tertiary care is provided by some general hospitals, teaching hospitals, specialist hospitals or other public or private units, which offer treatments in sub-specialties or interventions that use advanced equipment, such as those for the treatment of heart disease.

[3] Data from the health and welfare survey conducted in 2017 by the National Statistical Office, National Health Security Office.

[4] From a 2017 survey of private hospitals (based on 2016 operating result); the survey is carried out every five years by the National Statistical Office, the Ministry of Digital Economy and Society.

[5] Data on foreign patients comes from a paper outlining the strategy for developing Thailand as an international medical hub between 2017 and 2026 issued by the Department of Health Service Support.

[6] These countries are: Australia, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States.

[7] Good health at low cost, 25 years on: what makes a successful health system?’ World Health Organization.

[8] The Universal Coverage Scheme (also called the Gold Card or the 30 Baht Healthcare Scheme) began operating in 2002 under the management of the National Health Security Office (NHSO) and is the largest of the healthcare funds. The fund guarantees access to treatment for all Thai citizens without restriction, and covers around 80% of the population. The majority of those who use the Gold Card are low-income earners, those who work in informal employment, the elderly, and those who do not have access to other medical funds, and these combined represent some 75% of the total population. The government is responsible for managing healthcare through both state hospitals and private medical providers that are partners in the scheme.

[9] The Social Security Scheme (SSS) is a form of social welfare that was first rolled out in 1990 under the management of the Social Security Office (part of the Ministry of Labour). The SSS is the second most important of the public healthcare funds and provides care for the ‘self-insured’, who account for around 10% of the population. Financing comes from three sources: premiums paid by participants in the scheme, employers’ contributions, and government funding. Payments made by the fund may be used for treatment in both public and private facilities. The Social Security Office pays hospitals for treatment with an annual lump sum, calculated on the number of ‘self-insured’ patients which the hospital treated over the course of the year.

[10] The Civil Servant Medical Benefit Scheme (CSMBS) has been in operation since 1963 and uses tax receipts to pay for treatment for civil servants and their families, who have the benefit of receiving medical care in either state or private hospitals without having to make any contributions themselves. Approximately 10% of the population is covered under this scheme.

[11] Classified as spending on healthcare that is greater than 10% of all household spending. Source: Household socio-economic survey, National Statistical Office.

[12] BLT Bangkok, The market for Chinese and Middle Eastern tourists: a golden opportunity for Thai tourism, 31 May – 6 June, 2018

[13] Medical Tourism: Industry Focus. KPMG Phoomchai Audit Ltd., February 2018

[14] Hospitals that are expected to float on the stock market include Bangmod hospital. [15] National Statistical Office, Bank of Thailand

[15] National Statistical Office, Bank of Thailand

[16] Euromonitor International forecasts that the size of the Thai middle class will rise steadily and that by 2020, 6 million Thai households will have an annual income of over USD 15,000.[17] Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are those which cannot be transmitted and the category includes some chronic conditions which may take a considerable period of time to cure and to recover from. Bangkok Hospital reports that 73% of deaths in Thailand occur due to NCDs, which is higher than the world average of 63%. This situation is likely to lead to significantly greater expenditure on healthcare.

[17] Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are those which cannot be transmitted and the category includes some chronic conditions which may take a considerable period of time to cure and to recover from. Bangkok Hospital reports that 73% of deaths in Thailand occur due to NCDs, which is higher than the world average of 63%. This situation is likely to lead to significantly greater expenditure on healthcare.

[18] National Statistical Office, Department of Disease Control