Over the period 2021-2023, the power generation sector will grow, supported by greater demand for electricity (a projected rise of 2.8-3.8% per year). In addition, the sector will be driven by the government’s investment support measures under the Power Development Plan and Alternative Energy Development. With this, we anticipate greater investment from players in the rooftop solar, biomass, biogas, and waste-to-energy segments. These players will benefit from government support that will take the form of a steady increase in electricity purchases during 2021-2024, and they would also be more competitive with better cost-control and access to raw materials. However, competition is expected to stiffen, with this coming from both large players that are stepping up the level of their investments and new entrants to the market that are backing renewables, and as such, operators will see only moderate growth in revenue.

Overview

Thailand’s power generation industry is structured in line with the enhanced single-buyer model with state bodies being the sole buyers and distributors of power through the national grid. The Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT) is both a producer and, by purchasing power from private-sector ‘independent power producers’ (IPPs) and ‘small power producers’ (SPPs), a buyer of electricity. It also has a monopoly in the distribution of electricity in the country. In addition, the Metropolitan Electricity Authority (MEA) and the Provincial Electricity Authority (PEA) are responsible for distributing power as well as buying electricity from ‘very small power producers’ (VSPPs) (Figure 1).

The most important features of the Thai electricity generation industry are as follows: (i) Unlike other goods, electricity cannot be stored and must be distributed to users immediately through a transmission and distribution system. (ii) Expanding capacity to meet future demand requires long-term planning because power stations take 5-7 years to construct depending on the type of power plant. This long-term plan is the national power development plan, which main objective is to ensure that electricity supply is sufficient to meet future demand. (iii) Hence, state bodies have a major role in managing generation and distribution, as well as setting tariffs and investment targets to increase supply to the national grid.

Electricity demand growth will depend on the following

- Rising domestic demand. This would be determined by the health of the economy. Generally, demand for electricity grows at 0.9-1.1 times the rate of GDP growth (Figure 2). In 2020, the major sources of demand were industrial, household and business sectors which accounted for 43.9%, 28.3% and 23.5% of national electricity consumption, respectively, and others 4.3% (Figure 3). Within the industrial sector, the food industry was the biggest consumer, followed by steel & basic metals, electronics, auto assembly, and plastics production. In the services sector, there was strongest demand from serviced apartments and guest houses, followed by department stores, hotels, retailers, and wholesale operations.

- Government policy: (i) The Power Development Plan (PDP) and the Alternative Energy Development Plan (AEDP) lays out the desired total generating capacity for each type of power plant[1]. (ii) They also set the pricing for renewable energy (because producing power from renewables costs more than electricity produced from fossil fuels, i.e. natural gas, coal, and oil), and this is now used to determine the feed-in tariff[2] (FiT). Previously, the adder system was used to calculate payments3/ (Box 1). (iii) The government also has plans to expand the power distribution network to support the increasing generation capacity, especially from renewable sources.

Private power producers have an increasing role in the sector, especially for VSPPs (Figure 4). In 2020, the private sector controlled 56.1% of power generating capacity, split between IPPs (28.7% of total power supply), SPPs (19.1%) and VSPPs (8.3%). The remaining 43.9% is produced by EGAT, which is also responsible for buying-in power from neighboring countries.

Power plant operators can be split into two groups, by fuel source.

- Fossil fuel. This includes plants that are fueled by natural gas, coal/lignite and oil, as well as large-scale hydropower plants. In 2020, 55.3% of the electricity produced in Thailand were fueled by natural gas (down from 72.0% in 2010), followed by coal, hydroelectric and oil (Figure 5).

-

Renewables and alternative sources. This includes plants fueled by biomass (generally agricultural waste), biogas (including manure, waste water from agro-processing industries, and bioenergy crops), waste (consumer and industrial), solar, wind and micro-hydro plants. Electricity from these sources contributed 10.0% of national electricity consumption in 2020 compared to only 2.1% in 2010.

Currently, proven reserves (P1) of natural gas in the Gulf of Thailand is 4.9 trn cubic feet[4], while annual national consumption is 1.3 trn cubic feet (source: Department of Mineral Fuels, December 2019). This means Thailand has sufficient supply for only another 4 years, after which we would have to import gas, most probably from Myanmar. Because of this, the PDP emphasizes the increasing use of renewables in power generation.

There are three major groups of private-sector players in the power-generating sector.

- Independent Power Producers (IPPs)

- Total installed generating capacity: Over 90 MW. These producers mainly use natural gas and coal to fuel their power stations. The most important players are (i) Ratchaburi Electricity Generating Holdings, (ii) Gulf JP NS, (iii) Gulf JP UT, (iv) Gulf Power Generation, (v) Ratchaburi Power, (vi) BLCP Power, (vii) Electricity Generating, (viii) Glow IPP, (ix) Global Power Synergy, (x) Gheco-One, and (xi) Eastern Power & Electric.

- Revenue: The revenues of players in this group are exposed to low risk because the IPPs sign long-term (25-year) power supply contracts with EGAT. Revenue is generated from two sources: (i) a guaranteed ‘minimum intake’ specified in the contract with EGAT, and (ii) power supply directly to the grid to meet demand. Hence, their revenues are dependent on national electricity consumption, although some players also get receipts from their investments in power-generating facilities overseas, including Myanmar, Laos PDR, Indonesia, the Philippines and Australia.

- Small Power Producers (SPP)

- Installed capacity required to qualify as an SPP: 10-90 MW. SPPs typically generate power from natural gas, coal, oil and renewables, and sell mostly to EGAT. A small proportion of their output is sold to industrial consumers that are located near the SPP’s power stations. SPPs can be split into (i) ‘firm’-type SPPs, which have a 20-25-year contract to supply power to EGAT and are normally fueled by natural gas or coal, and (ii) ‘non-firm’ SPPs, which have 5-year contracts (extendable in 5-year increments) and are normally fueled by renewables such as such as solar power, wind power, waste and biomass.

- Revenue: SPPs have two primary sources of revenues. (i) Derived from long-term contracts with EGAT that, like IPP contracts, come with a minimum revenue guarantee. This means SPPs only have mild exposure to risk of weak earning. (ii) Derived from supplying electricity to industrial consumers located close to the power stations. However, this revenue can fluctuate according to the overall economic conditions and the individual industry cycles. Beyond this, some players also receive returns on investments in power assets overseas, including solar-based electricity generation assets in Japan, China and Taiwan, and wind-power assets in Vietnam.

- Very Small Power Producers (VSPPs)

- Installed capacity to qualify as a VSPP: Under 10 MW. VSPPs typically generate electricity from renewables (including solar, wind, hydropower, biomass, biogas and waste) for their own use, and sell any surplus production to MEA or PEA at rates determined by the feed-in tariff (FiT) for that particular generating technology and other circumstances for as long as the project runs (Box 1). The majority of VSPPs that sell electricity fueled by renewables are involved with engineering, designing, procurement and construction, or manufacturers of solar cells and related equipment, as these operators have the necessary expertise to install and maintain the renewable electricity systems.

- Revenue: VSPPs supply electricity to the MEA or the PEA according to conditions specified in their contracts. They will receive payment when the electricity enters the grid (i.e. it is a COD system). Players that generate power from natural sources (i.e. solar, wind or hydropower) are likely to run at a loss in the first 1-2 years due to high cost of building and outfitting production sites, but following this initial period, the situation will improve supported by revenue from the sale of electricity. However, earnings could be volatile for players which produce electricity from biomass, biogas and waste, because of limited access to and fluctuating prices of raw materials

Between 2010 and 2020 the share of electricity produced by SPPs and VSPPs had surged with government support under the AEDP and increasing purchases of electricity from this group of suppliers. By 2020, their contribution to the national energy mix had jumped to 5.4% of all electricity sold through the grid from only 0.7% in 2010 (Figure 6). The major players in the energy sector that are listed on the stock exchange and that produce power from renewables include Energy Absolute (EA) (solar and wind), SPCG (solar), Gunkul (solar, wind and biomass), TPC Power Holdings (TPCH) (biomass), Thai Solar Energy (TSE) (solar and biomass), and Power Solution Technologies (PSTC) (solar, biomass and biogas) (Figure 7). Some of these companies also invest in renewables-based power generation assets abroad.

Situation

National electricity consumption declined by 3.1% to 187,046 gigawatt-hours (GWh) in 2020 (Figure 8). Demand dropped across the year with the spread of COVID-19 and the accompanying slowdown in the economy. This was manifested in historically severe drops in demand for electricity in the business (-10.5%) and industrial sectors (-4.6%), which together account for 67.4% of national demand for electricity. Businesses that reported the most acute slide in electricity consumption tended to be those connected to tourism, including hotels (for which demand slid 36.4%), restaurants (-18.4%), department stores (-15.5%), and apartments and guesthouses (-9.6%). In the industrial sector, declines were largest in textile production (-18.9%), auto assembly (-18.7%), steel and basic metals (-8.9%), and chemicals (-4.1%). However, in the household sector, the upsurge in working from home (especially during the second quarter) helped to move demand in the opposite direction, and for all of 2020, this jumped 7.4%. Peak demand fell 7.2% to 28,636.7 MW, down from a record-breaking of 30,853.2 MW in 2019.

2020 national power generation fell 2.9% to 205,995 GWh. EGAT (providers of 32.3% of total national supply) increased generation by 1.9%, private-sector power generators (53.4% of total supply) cut their contribution by 9.3%. Within the private sector, IPPs (22.0% of total supply) reduced output by 17.9%, while SPPs (26.0% of total supply) and VSPPs (5.4% of total supply) cut their output by 2.1% and 2.5%, respectively (Figure 9). In terms of power sources, electricity generation from natural gas (55.3% of all power generation) and renewables (10.0% of supply) dropped by respectively 6.3% and 4.2%, while supply from coal (17.9%) and imports (14.3%) rose by 2.8% and 15.7%.

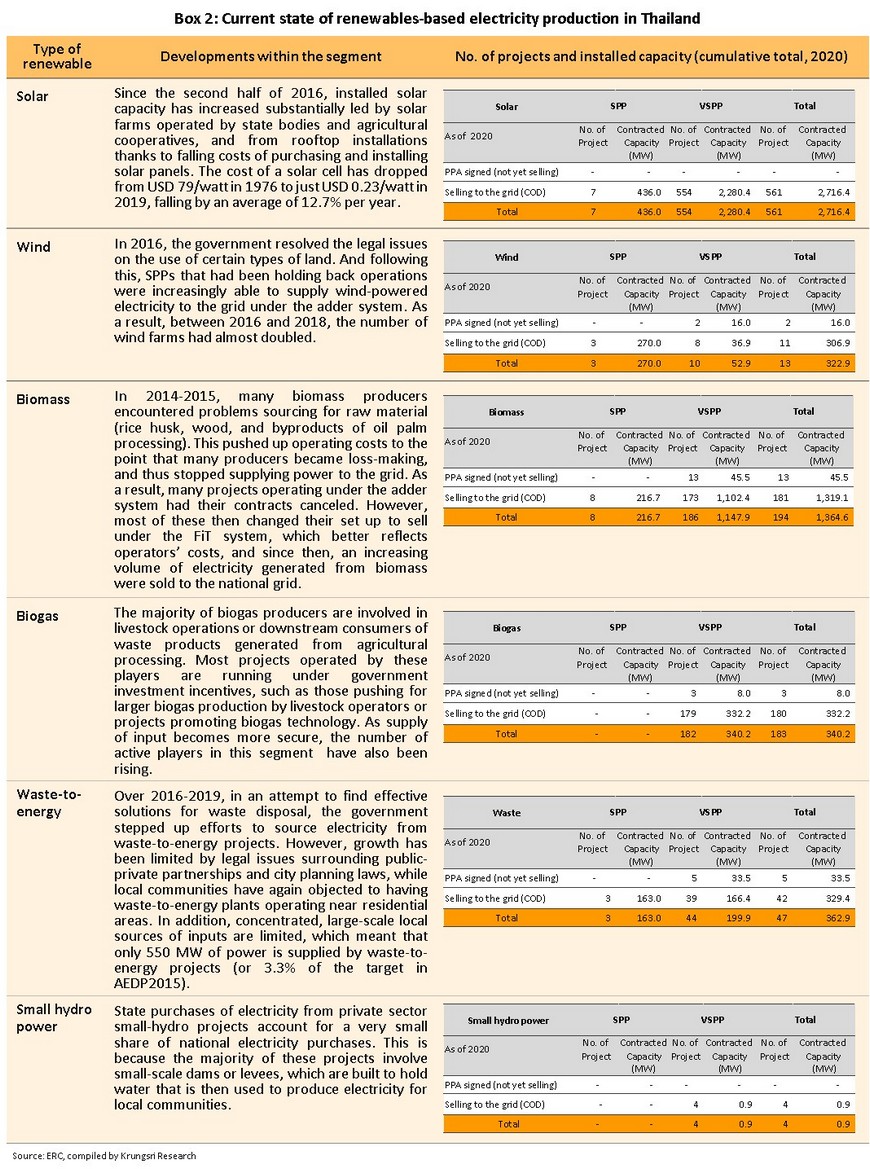

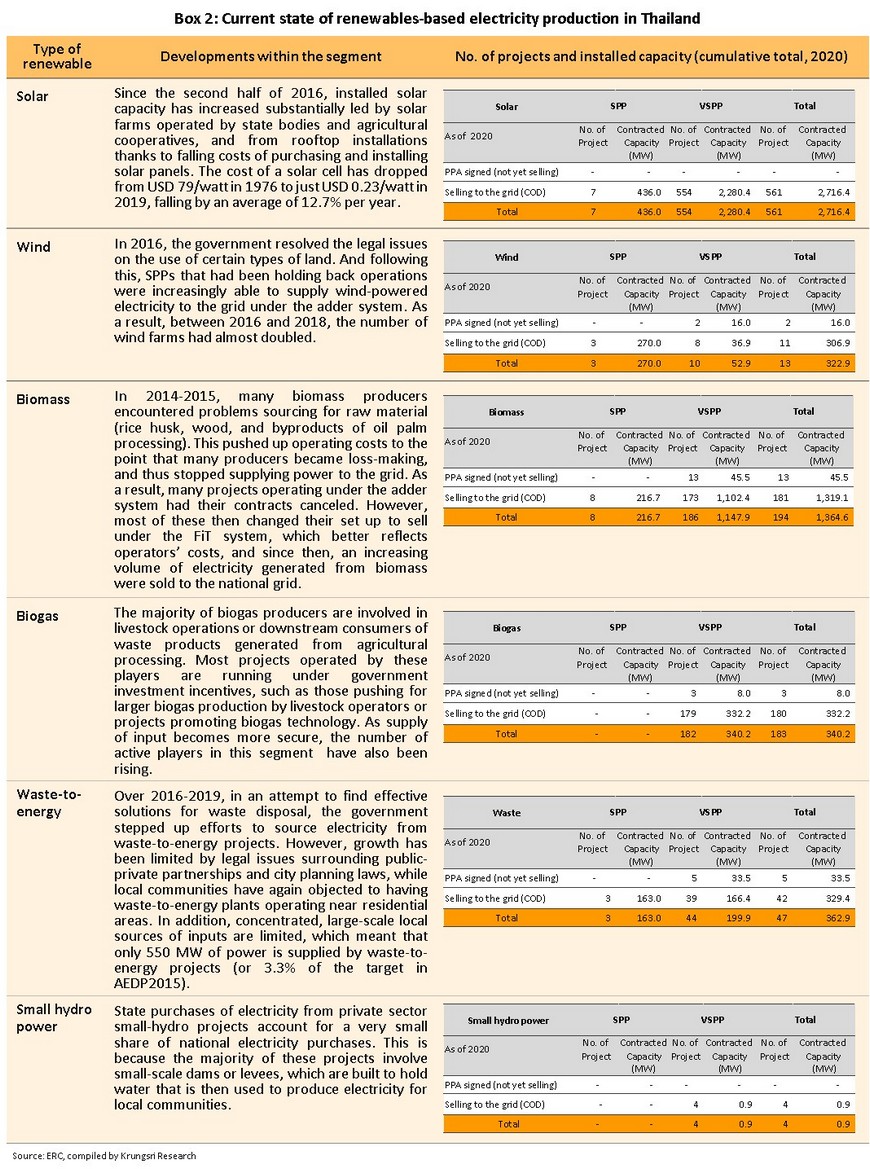

In 2020, installed capacity for renewable-generated electricity under contract to sell into the grid rose 1.4% to 9,053 MW[5] (Figure 10), with this rising by 3.3% for biogas electricity production, 3.1% for waste-to-energy and 2.7% for biomass. However, actual electricity generation is only 53% of the way toward meeting the target laid out in AEDP2015 of having 16,778 MW of renewable-powered supply by 2036. By segment, biomass generation has performed best and supply is now 63% of the target, followed by waste-to-energy (59% of target supply), small hydro (51%), solar (50%), wind (50%) and biogas (43%) (Figure 11).

In 2020, a total of 979 renewables-based SPPs and VSPPs had passed their official ‘commercial operation date’ (COD) and were thus supplying power to the grid. This includes those operating under the Adder and FiT programs, and all together, these had a combined contract capacity of 5,004.1 MW. In the year, the number of waste-to-energy projects rose 3.6%, while that of biomass increased by 2.0% (Box 2).

Outlook

Over 2021-2023, the outlook for private-sector electricity generators will improve, boosted by economic recovery and government support to invest more in the sector, as specified in the PDP.

Total domestic electricity consumption is forecast to increase by an average of 2.8-3.8% per year[6]. This will be driven by an anticipated recovery in the economy (Figure 12) that will lift demand for electricity in both the business and industrial sectors. Demand from the household sector will also continue to rise, helped by the periodic need to work from home, especially in 2021.

Power Development Plan for 2018-2037 (PDP2018, 1st revision) encourages the expansion of private-sector installed capacity and investment in new power stations with the following goals.

- The plan targets 56,431 MW of installed capacity by 2037 (Table 4). This supply will come from the following sources: (i) natural gas contribution will be unchanged at 53%; (ii) electricity generated from renewables will play a larger role with their contribution rising to 21% from 20%; and (iii) coal-fueled generation will fall to 11% from 12% (Table 5).

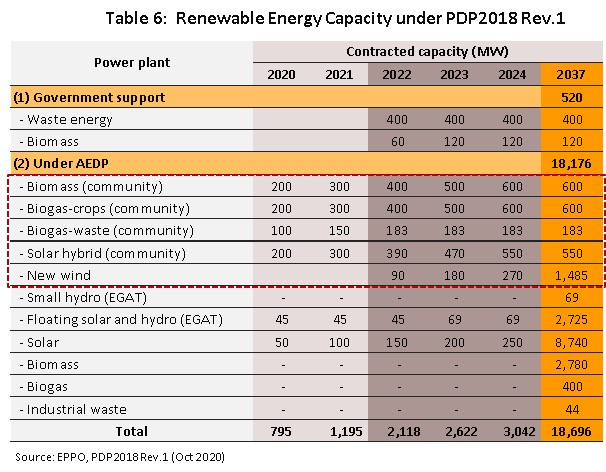

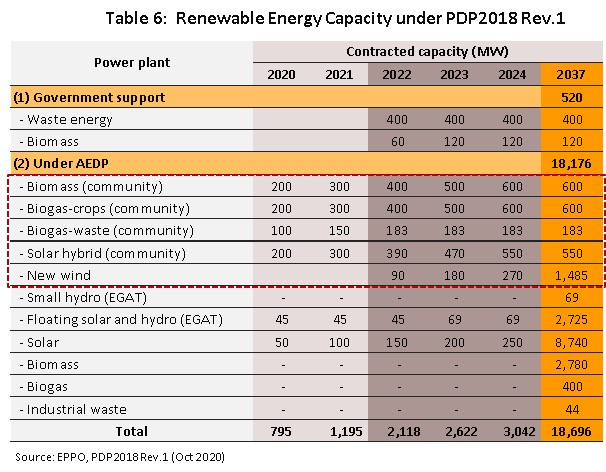

- The roadmap laid out in the PDP2018 and AEDP2018 will underpin increased investment in electricity generation from renewables. The overall target for the purchase of renewables-fueled electricity is set at 18,696 MW by 2037, comprising: (i) 520 MW from power plants per planned government support for the industry. Between 2022 and 2024, 400 MW will come from waste-to-energy sources and 120 MW will be from government-run biogas facilities in the south of Thailand (“Pracharat” power plant); and (ii) 18,176 MW from renewables projects per the AEDP, which includes 1,933 MW of new capacity from local, community-based power generation capacity from biomass, biogas (from waste water and energy crops), and solar hybrid systems in 2020-2024, and 270 MW of wind power which will come on-stream in 2022-2024 (Table 6).

- From 2024, consumer electricity tariffs are expected to average THB3.64/unit, up from THB 3.58/unit specified in the earlier version of the plan. This is partly due to buying electricity from community-level producers, for which the government has set initial purchase price at THB 3-5/unit, aimed at encouraging greater investment in renewables

The above factors will encourage more investment in the three types of power generation projects, as described below.

- For IPPs, there should be competitive bidding for a large number of new power stations in the coming period. The government will call for bids for about 700 MW of capacity in the west of the country in 2021-2022, to replace 8,300 MW of natural gas-powered plants that will gradually reach the end of their supply contracts and lose access to the grid over 2025-2027.

- SPPs would increase installed generation capacity and investment in new power stations, especially natural gas-fueled cogeneration power plants which contracts will expire in 2019-2025[7]. SPPs will also invest in renewables in the form of mixed-fuel power generation, or ‘SPP hybrid firms’, which Thai authorities are increasingly supporting. These power suppliers will now be paid for the next 20 years at a feed-in tariff rate of THB 3.69/unit, up from the THB3.66/unit received in 2019.

- VSPPs are expected to step up investment from 2021, especially in solar rooftop, biomass, biogas and waste-to-energy electricity projects. In line with the PDP and AEDP, the government is supporting these segments by increasing purchases of electricity from these suppliers. For biomass producers, the government plans to buy 100 MW of supply annually from community-level producers and another 60 MW annually from the Pracharat power plant in the South. For the biogas segment, the government intends to purchase 100 MW of electricity annually from community-level power plants generating electricity from energy crops. For waste-to-energy electricity projects, the government plans to buy 400 MW of electricity over 2018-2037. These players are also generally competitive in terms of access to raw materials and costs. For players active in wind power, the government plans to buy-in another 270 MW of electricity from wind farms over 2022-2024, by which time EGAT should have completed its work on the high-voltage power lines in the Northeast and South, which are required to connect commercial wind farms to the grid.

In the coming period, competition in the sector will tend to stiffen as large players are incentivized to invest in additional capacity by the provisions of the PDP. These specify that sufficient baseload power plants be ready and connected to the grid, though the PDP also opens the door to making additional purchases of electricity from the private sector, especially for renewables. As a result, larger operators (IPPs and SPPs) that have access to the requisite financing and technology will have the opportunity to invest in new power plants running on renewable sources and to expand their installed renewables capacity. At the same time, players that have a background in engineering, procurement and construction have the necessary expertise to install electrical systems, or those that manufacture solar equipment. These operators have started to supply renewable power to the grid. This increased level of activity will then feed into greater levels of competition, especially for players in the biomass and biogas segments, where competitive bidding[8] may also work to suppress profits.

Future challenges to the industry will tend to revolve around the use of technology and innovation to produce power from renewables and how this plays out with regard to the efficiency of power production, and its environmental impacts and costs. (i) The sharp drop in the cost of solar cells now allows solar energy to compete effectively on price with power generated from other sources. This is especially true for rooftop solar installations on domestic residences, office buildings and factories. (ii) Investment in the production of semi-solid batteries will be an important factor in raising the efficiency of renewables power production (e.g., for solar- and wind-powered electricity, or for hybrid sources of power). (iii) Developing smart energy storage systems (ESS) will increase the efficiency of energy storage and use. At present, Global Power Synergy (GPSC) is working with PTT Global Chemicals (GC) to develop an ESS to increase the efficiency and security of power distribution to offices and to the Center for Innovation and Technology in Rayong and to the pilot smart city being run by the Vidyasirimedhi Institute of Science and Technology.

In addition, changes to government policy have opened the way to greater private-sector participation in energy production, for example through the introduction of private power purchase agreements. These provide a mechanism for private sector players to sell electricity directly to one another, and this will then lead to consumers also acting as electricity producers and retailers[9] (or as so-called ‘prosumers’). This will be especially important for producers of solar power because recently, the cost of generating electricity from solar sources has collapsed, falling from THB 6-7/unit in 2016 to just THB 2/unit now, and this will incentivize consumers to increasingly begin producing power themselves, although in practice, technological problems persist that still need to be solved before renewables can play a major role in powering the grid. These include overcoming the impacts of fluctuations in power output on supply to the grid, removing technological restrictions on energy storage, and overhauling the electricity grid and related systems so that these are sufficiently flexible that they can serve the needs of prosumers (e.g., facilitating purchases of electricity and user management).

Krungsri Research’s view

Players will see stronger revenue growth in 2021-2023, supported by greater demand for electricity in line with the improving economic outlook. However, competition in the sector has grown more intense, as there is increasing influence from renewables, which could cap revenue growth.

- IPPs: Revenue should rise driven by stronger domestic consumption of electricity and higher returns from overseas investments. Domestically, there will be more investment in renewables, encouraged by the revised PDP2018 plan, which allows competitive bidding for only 700 megawatts of generation capacity to replace gas-fired power stations in 2021-2022. Overseas, there will be more investments in new natural gas- and coal-fired power stations and renewables (especially solar and wind) in Myanmar, Laos PDR, Indonesia, the Philippines, Australia and Japan.

- SPPs: Revenue will rise steadily due to: (i) cogeneration natural gas power stations (that will reach the end of their contracts over 2019-2025) will still be able to supply power to industrial parks and estates; (ii) new renewables projects in the form of ‘SPP hybrid firms’, which will enjoy fuel costs that are lower than consumer prices for electricity (costs about THB 1.81/unit whereas consumer prices are about THB 3.60/unit); and (iii) new electricity production in the Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC), where demand will rise in the near future.

- VSPPs: Revenue will continue to grow driven by stronger demand, but investment opportunities may be restricted to producers that are beneficiaries of government support measures laid out in the revised PDP and AEDP, notably private rooftop solar, biomass, biogas and waste-to-energy projects from which the government plans to increase electricity purchases. New entrants to the market that are investing in biomass, biogas and waste-to-energy projects may experience difficulty sourcing for input, while government purchases of electricity from new wind-powered projects should start in 2022-2024. However, competition will tend to intensify because existing operators have been expanding generation capacity and there have been several new entrants. Notably, there is increasing influence from players with huge financial and technological strengths, such as IPPs and SPPs and players that have a background in engineering, procurement and construction because they have the necessary expertise to install electrical systems, or those that manufacture solar equipment. To build new revenue streams, these operators have started to supply renewable power to the grid.

[1] In the past, this was a 15-year framework, which was then extended to 20 years. At that time, the Energy Policy and Planning Office (EPPO) undertook planning in cooperation with the Department of Alternative Energy Development and Efficiency (DEDE) but planning for 2018-2037 is within the remit of the PDP and the AEDP.

[2] The net price for purchases of electricity is set at a rate that reflects the real costs of production of different types of power over the course of the 20-25 years for which contracts to supply run. These are allotted through a process of competitive bidding organized by the Office of Energy Regulatory Commission (ERC).

[3] Under this system, an additional payment is added to the cost of electricity sold to the grid for a period of supply running for 7 years. Admission to the system is on a first-come, first-served basis.

[4] Reserves are in deposits that have already been explored. Plans, which have been approved in accordance with national laws, have been put in place for the exploitation of these reserves and extracting this gas should be commercially viable

[5] Includes capacity that is used outside the system (e.g., electricity that is produced by a business for its own use) but does not include 2,906 MW of capacity from large-scale hydro.

[6] On the assumption that (i) energy-saving measures cover 1bn units per year, and (ii) some private-sector players producing power for themselves (IPS) do not distribute power to EGAT and/or sell this directly to their customers, but at present data is only available for those generating more than 1 MW.

[7] This specifies that SPPs should build new power stations and that the electricity produced from these should be sold to EGAT. These power plants should generate electricity from the same sources as before, and payment for this should be set at the rate for electricity produced from natural gas or coal.

[8] Bids are arranged in order of the fixed FiT discount rate from high to low. VSPPs that make the offer with the steepest discount will be considered for selection, with consideration given to the potential of the generating system used and the quantity of electricity that will be supplied to the grid, relative to target purchases

[9] EGAT defines this as production by the consumer. Under this scheme, consumers that have a solar rooftop installation are able to sell any surplus electricity to nearby houses

.webp.aspx)