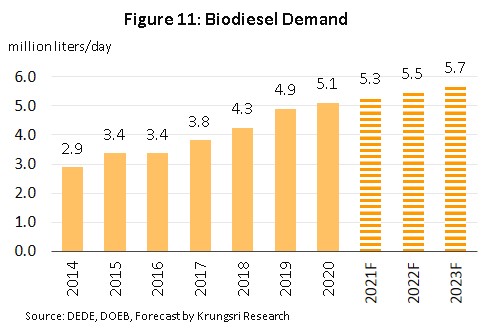

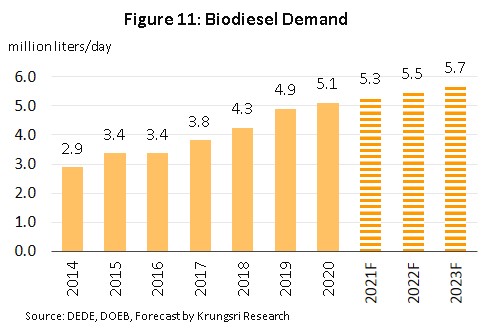

Over the next three years, the biodiesel industry will enjoy improving business conditions thanks to an average annual increase in domestic demand of 3.0-4.0%, which will then bring consumption to 5.3-5.7 million liters per day. This outlook is supported by: (i) stronger demand for diesel from the transport sector, which will be driven by a rebound in economic activity, ever-greater e-commerce sales and a steady rise in the number of diesel-powered vehicles on Thai roads; (ii) government efforts to rebalance the palm oil market, together with the increase in the total area of oil palm under cultivation and the resulting growth in supply; and (iii) the move by auto manufacturers to put greater efforts into developing diesel engines that can run on fuels that have a high biodiesel content.

Despite the generally positive outlook, challenges will remain for the industry, including uncertainty over security of supply of inputs (i.e., of palm oil), the possibility that government intervention in the market to help palm growers may affect the price of inputs, and the government support in electrical vehicles production. Because of this, future profits may come under threat.

Overview

Biodiesel, or alternatively B100, is a fuel that can be produced from a range of biological inputs including plant matter, animal fats, and waste cooking oil. By using alcohol-based chemical processing, these raw materials are converted into ethyl ester or methyl ester, which have properties similar to regular mineral diesel. Biodiesel can then be mixed with the latter, saving on the import of some oil products and, thanks to this, biodiesel production provides the country with a means of achieving a greater degree of security over its energy supplies.

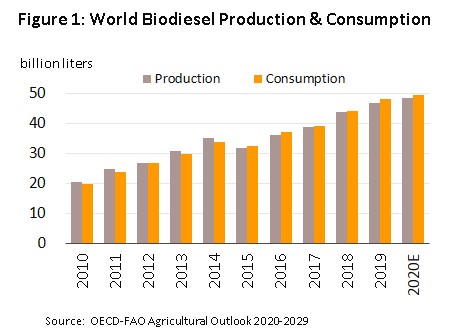

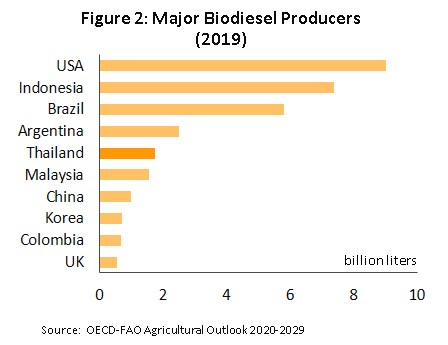

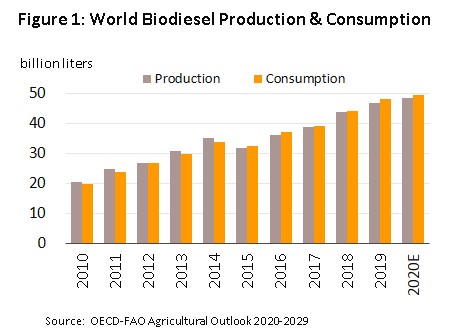

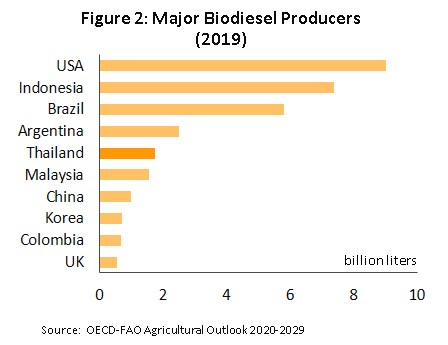

Globally, both demand and production of biodiesel have been increasing steadily, and between 2010 and 2020, world consumption rose from 19.8 to 49.4 billion liters (or average growth of 11% per year) (Figure 1), with biodiesel now widely used in Europe, the United States, Canada, Latin America, Australia, Japan, and some other Asian countries. At the same time, production rose at a slightly slower though still rapid annual rate of 10%, output jumping from 21.0 to 48.3 billion liters over the same period. The United States, Indonesia and Brazil are the world’s largest producers (Figure 2), with this biodiesel typically produced from rape seed, sunflower, coconut, soy bean, oil palm and jatropha. As for Thailand, the country currently sits in 5th place in the global production rankings, with its biodiesel manufacturers generally using crude palm oil as their primary input.

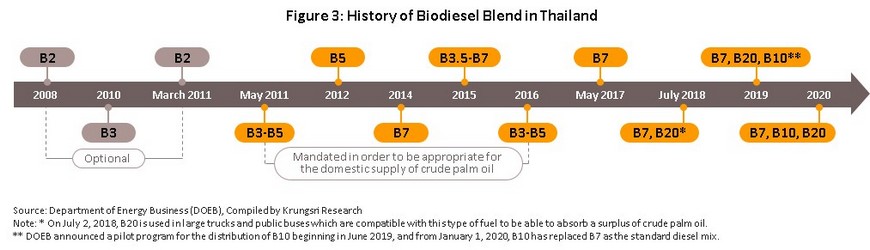

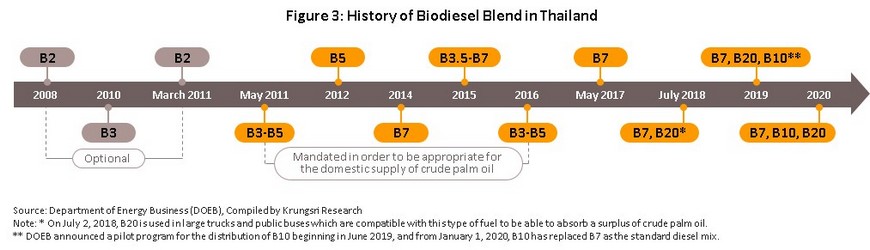

The production of biodiesel for mixing with standard diesel began in Thailand in 2007, although at first, this was restricted to a 2-3% mix (or B2). This then increased to 5% (B5) in 2011, 7% (B7) in 2014 and 10% (B10) in 2019 (Figure 3). Naturally, this steady increase in the proportion of biodiesel mixed in standard diesel has fed a rise in demand for biodiesel overall, but the government has adapted the mix to the quantity of oil palm available on the domestic market and when there have been shortages, the mix has been reduced. Thus, in 2016, the mix was cut from 7% to 5% in July and then again to 3% in August as the market tightened and the government tried to maintain stability and prevent a shortage of palm oil, but as supply improved, the mix was increased again, rising to 5% in November of the same year. Thai biodiesel production is almost entirely consumed domestically, while imports of biodiesel need to be approved by the Department of Energy Business.

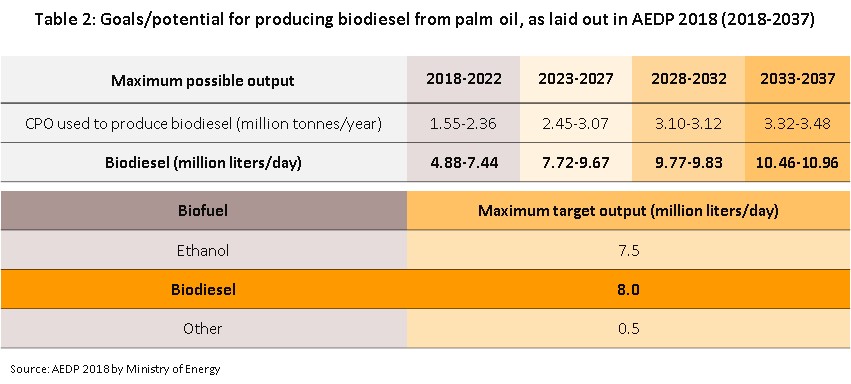

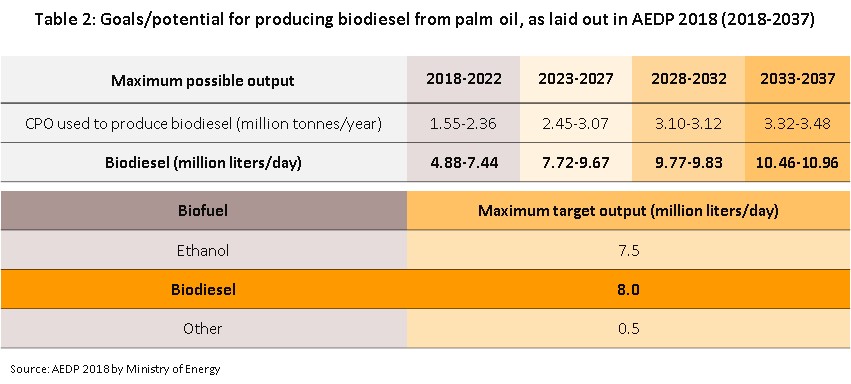

Government support for the industry is laid out in the Alternative Energy Development Plan, or AEDP, and this is extremely important in determining how the biodiesel sector develops, particularly with regard to ensuring that the domestic supply of oil palm is sufficient to cover demand from the industry and that investment is promoted. The sector has thus been the recipient of investment support policies carried out under the auspices of the Board of Investment (BOI), and for investors in biodiesel production, this has included an 8-year exemption from corporate income tax, a 5-year 50% reduction in tax on profits, and the waiving of import duties for machinery used in biodiesel production.

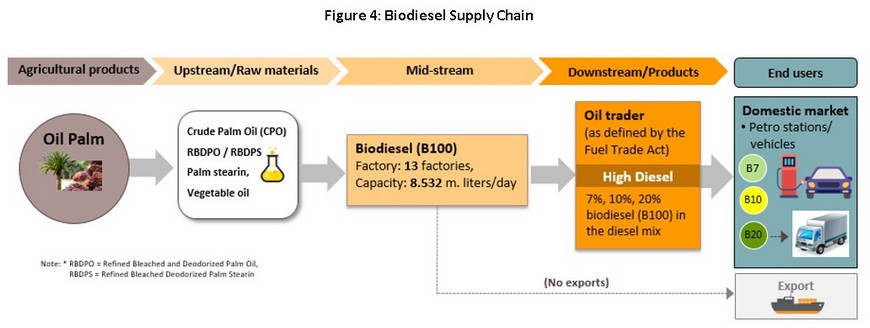

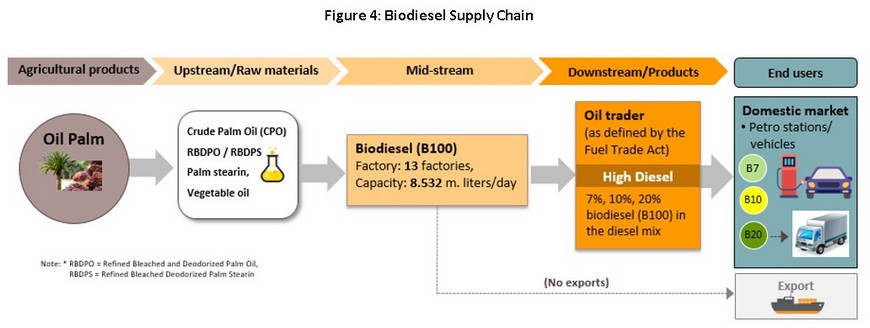

In Thailand, biodiesel is mostly produced from crude palm oil (CPO), although Thai manufacturers also use refined bleached and deodorized palm oil (RBDPO), palm stearin and other vegetable oils (Figure 4). In 2020, a total of 5.9 million rai was given over to oil palm production, and this yielded 16.2 million tonnes of raw oil palm, which in turn produced 2.9 million tonnes of CPO. Of this, 1.4 million tonnes, or 48% of all national production of CPO, was directed to biodiesel refiners, with the rest going to household consumption.

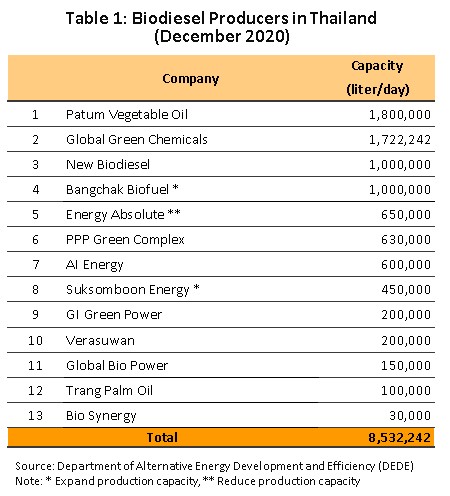

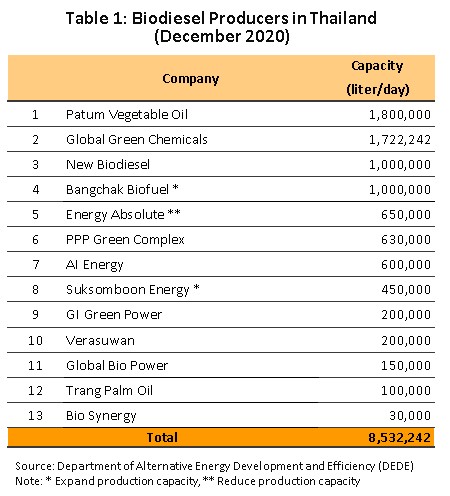

The relatively low number of players active in the industry means that the biodiesel market is not affected by high levels of competition, and as of December 2020, there were only 13 biodiesel producers registered with the Department of Energy Business, the majority of which are downstream companies that are part of commercial groups active in growing palm oil, oil refining or petrochemicals. These have a combined production capacity of 8.5 million liters per day, up from 8.3 million liters per day in 2019. In order of capacity, the most important players are Patum Vegetable Oil, Global Green Chemicals, New Biodiesel, Bangchak Biofuel, and Energy Absolute (Table 1). Their output is consumed primarily by the domestic market, while community-level small-scale biodiesel production[1] is mostly used by the agricultural sector in the north, northeast and south of the country.

For manufacturers, the largest share of production costs goes to raw materials, in this case usually CPO, which accounts for some 70% of the total. Chemical inputs run to another 20%, and the remaining 10% goes to operating costs. As set out in the 2000 Fuel Trade Act, the domestic price of pure biodiesel is determined by the Committee on Energy Policy Administration, and this is used as the reference price[2] in trade by distributors and refineries.

Operators’ profits are determined by two major factors: (i) government policy towards alternative energy[3] and the setting of a biodiesel mix that matches demand with the supply of raw materials[4], and (ii) the difference between the sale price and the cost of inputs. (Oil refineries and traders may have a stronger negotiating position than biodiesel producers and so they may be able to set purchase prices at a level that diverges from the reference price.)

Situation

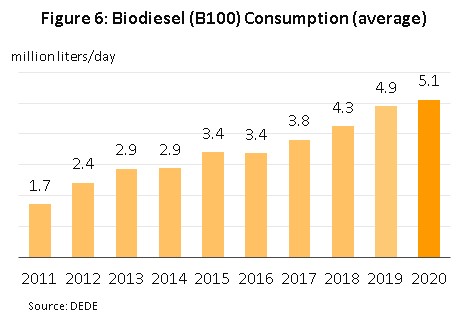

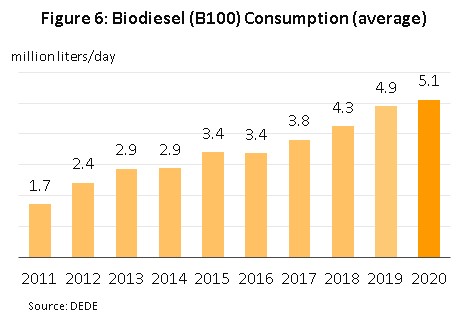

The Thai biodiesel industry has seen steady growth over the recent past thanks to stronger demand driven by growth in the economy and an increase in the size of the national diesel-powered vehicle fleet. In addition, the market has been boosted by the Alternative Energy Development Plan, which has sought to increase the use of alternative energy as a way of both supporting the price of palm oil and increasing national energy security. As such, daily biodiesel consumption has risen from 1.72 million liters in 2011 to 4.25 million liters in 2018 (or 6.7% of all high-speed diesel), an average annual rise of 13.8%. Over the same period, output has risen at a slightly higher rate of 14.1% per year, jumping from 1.73 to 4.34 million liters per day (Figure 5).

Steadily falling prices for palm oil in 2019 encouraged the government to increase the proportion of biodiesel in the diesel mix as they tried to support producers. From October 2019, the government thus incentivized greater consumption of B10 and, for large commercial vehicles, B20 by cutting pump prices for these by respectively THB 2 and THB 3 below the price of B7 (standard diesel). As a result, consumption of biodiesel jumped 15.3% to 4.9 million liters per day (or 7.6% of all diesel consumed nationally), while its average price slipped to a 10-year low of THB 25/liter.

In 2020, the outbreak of COVID-19 undercut demand as travel slowed and the economy slipped into a severe recession (GDP fell 6.1%), while the continuation of the severe drought into the first half of the year also eroded demand for the transport of agricultural goods. Nevertheless, demand for biodiesel (B100) still rose, climbing to 5.1 million liters per day, or growth of 4.3% from 2019 (though this was a sharp fall on average annual growth of 11.3% over the previous 5 years) (Figure 6). Overall, biodiesel now accounts for 8.1% of the 63.5 million liters of high-speed diesel consumed nationally each day. Factors supporting a continuing rise in demand include the following:

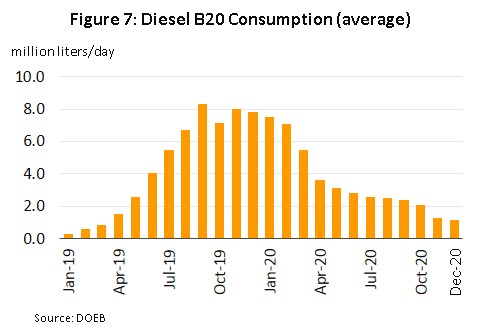

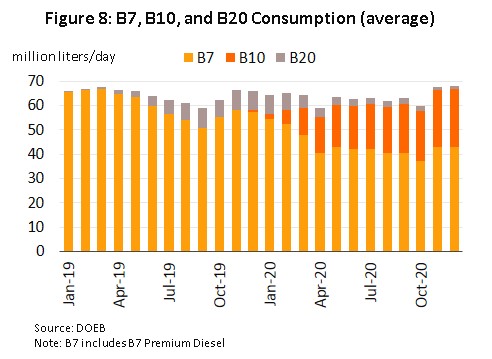

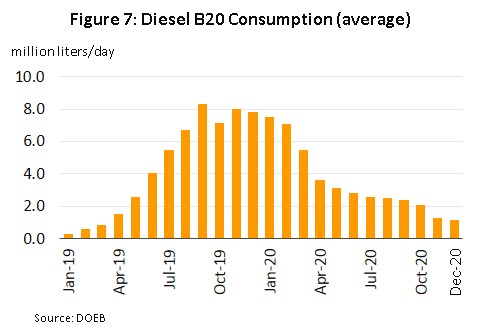

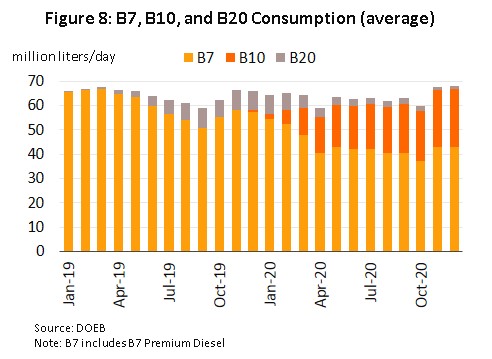

- The government’s decision to soak up excess supply of raw oil palm products by steadily raising the proportion of biodiesel in the diesel mix has helped to underpin stronger demand. Thus, B10 has now replaced B7 as the standard diesel mix (from January 2020), with the latter now being used only in older vehicles and some European models that are unable to run on B10. The government has also set B20 as the preferred choice for larger commercial vehicles and is now attempting to ensure that B10 is easily available on forecourts nationwide. The government has also been using price mechanisms to influence the market, and price support for B10 and B20 rose from the start of the year from respectively THB 2.0 and THB 3.9 per liter to THB 2.5 and THB 4.2[5]. Because of this, pump prices for B10 and B20 were THB 3.0 and THB 3.5 per liter below those of B7. For all of 2020, consumption of B20 averaged 3.5 million liters/day (5.5% of all high-speed diesel consumed nationally), down 21.9% from 2019 (Figure 7). For B7, consumption averaged 43.8 million liters/day (69.0% of all diesel), down 26.8%, while for B10, daily consumption came in at 16.2 million liters (25.5%, up from just 0.2% in 2019) (Figure 8).

- The number of diesel-powered vehicles registered in Thailand is also rising, and in 2020, this increased 3.2% to 11.7 million. This is driven partly by an increasing desire to use private rather than public transport and partly by strong growth in the e-commerce sector, which is feeding into greater demand for delivery services. Thus in 2020, vehicle registrations were up 210,000 (+6.6%) for cars, 120,000 (+1.8%) for pick-ups, 20,000 (+2.5%) for large commercial vehicles, and 10,000 (+2.2%) for tractors, rollers and other agricultural vehicles, but down 9,000 for buses (-6.9%).

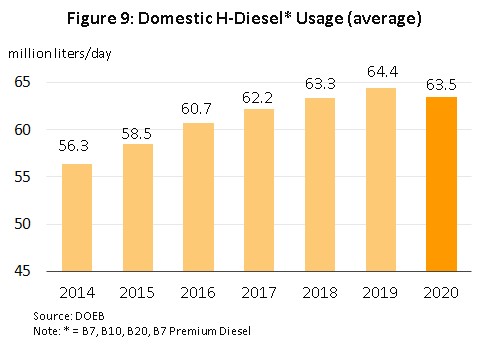

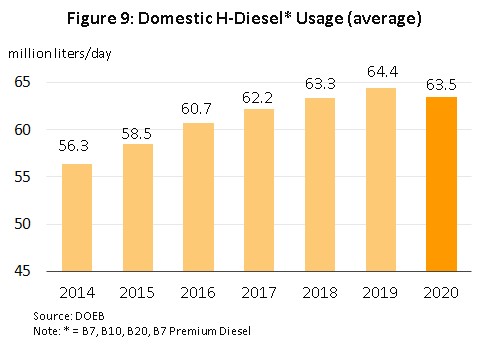

The various factors described above combined to cut 2020 sales of high-speed diesel by 1.5% to an average of 63.5 million liters per day (Figure 9).

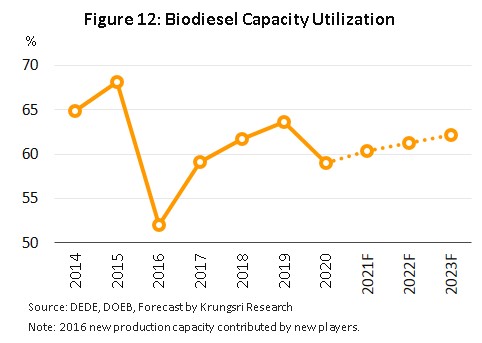

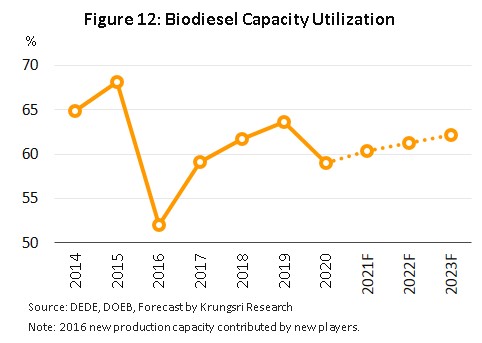

2020 output of biodiesel slipped 0.3% to an average of 5.0 million liters per day on a fall in overall demand for diesel, though this decline was strongest during the lockdown in April. This drop occurred despite an additional 220,000 liters per day of new capacity coming online, and this was one factor behind the slump in capacity utilization, which declined to a 3-year low of 59.0%.

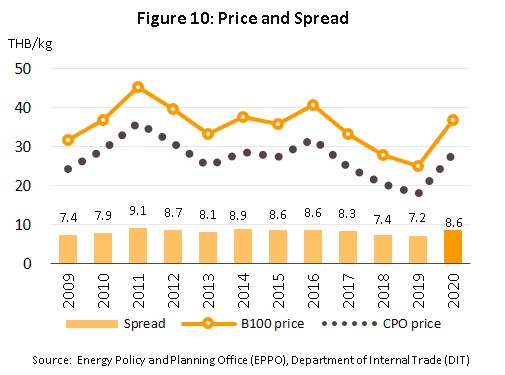

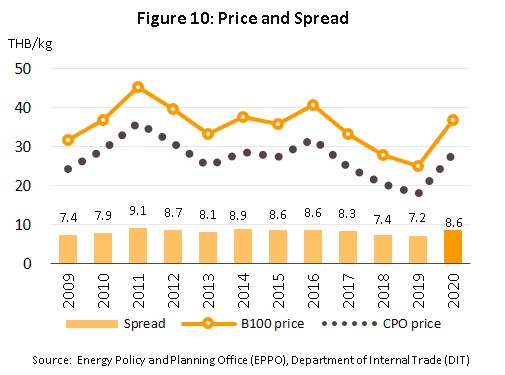

In 2020, the reference price for sales of biodiesel to traders rose 46.8% to THB 31.8 per liter or THB 36.7 per kilogram[6] on a 57.9% jump in the price of CPO and of 58.6% in that of palm stearin. These price rises were driven by the impact on oil palm yields of the drought that dragged into the first half of the year, and by the increase in the standard diesel mix to B10, which raised demand for CPO in the energy sector. At the same time, demand for CPO was further intensified by its use in electricity generation and by the export of a further 300,000 tonnes. This then widened CPO-biodiesel spreads by 19.4% to THB 8.6 per kilogram (Figure 10).

Outlook

Krungsri Research sees demand for biodiesel rising by an average of 3.0-4.0% per year over the period 2021-2023 (Figure 11) to 5.3-5.7 million liters per day. This outlook will be supported by the following factors:

- Demand for diesel in the transport sector will tend to strengthen on: (i) recovery in the Thai economy and forecast annual growth of 3.0%; (ii) expansion in Thai e-commerce that e-Conomy SEA 2020 predicts will lift the value of the market from USD 9bn in 2020 to USD 24bn in 2025 (average growth of 21.0% per year) and that will drive stronger demand for commercial delivery services, and especially for the use of pick-up trucks; and (iii) an average annual 3.0-4.0% expansion in the number of diesel vehicles registered in Thailand

- Government efforts to balance the market for palm oil are also feeding stronger demand for biodiesel, most notably with the 2020 switch from B7 to B10 as the standard diesel mix, though this will likely rise again in the future in line with an anticipated expansion in the domestic supply of palm oil. The latter will be driven by the government’s efforts to increase the total area of oil palm plantations from 5.9 million rai in 2020 to 10 million rai by 2029 and to lift daily CPO production to around 3.0-3.2 million liters, which should then help to keep the cost of inputs relatively flat for biodiesel producers. These moves to increase domestic consumption of biodiesel are also in step with those of other regional governments: in Malaysia, B20 should replace B10 as the standard diesel mix in December this year, while in Indonesia, B40 should replace B30 as the standard mix in 2022.

- Auto manufacturers are developing new engines that are capable of running on diesel mixes with a higher biodiesel content, and these will be available for large vehicles, pick-ups, SUVs and trucks. At present, Isuzu and Toyota control 80% of the market for pick-ups that can run on B20.

Krungsri Research forecasts domestic demand for high-speed diesel7/ rising by an average of 2.0-3.0% per year over 2021-2023. Over the next 3 years, demand for B7 will drop to 28.0-30.0 million liters per day from 2020’s daily demand of 43.8 million liters, while for B10, consumption will rise from 16.2 to 32.0-38.0 million liters per day. However, demand for B20 will remain relatively weak since its price is similar to that of B7 and B10, a result of the government’s decision to relieve pressure on the Oil Fund by cutting price support for B20, and consumer fears that using B20 may have long-term effects on their vehicles and/or require them being retuned or fitted with additional equipment. Nevertheless, the government still plans to raise the standard mix above B10 when the conditions are right, and officials have a long-term plan to increase the diesel mix to 23% biodiesel by 2037. Krungsri Research thus expects that demand for biodiesel will continue to rise, and in response, manufacturers will expand their production capacity. Overall, capacity utilization is therefore forecast to rise only slightly, edging up to around 60.0-62.0% from its 2020 level of 59.0% (Figure 12).

Despite the generally positive outlook for the next few years, challenges remain for the industry. (i) Players will need to manage their production costs carefully since there is a possibility of periodic shortages of CPO, which would then tend to push up operating costs. (ii) It will also be necessary to increase consumer confidence in the use of biodiesel since different diesel engines have different capabilities with regard to using higher biodiesel mixes, and therefore, owners will need to have clear information about whether or not it is safe to use B10 or B20 in their particular vehicle. Over the long term, the increasing interest in electric vehicles also poses a threat to the industry. At present, the Department of Energy aims to have 30% of auto output being of electric vehicles by 2030 (as of 2020, electric vehicles accounted for only 3.5% of all new vehicle registrations), and it is expected that as soon as 2025, the purchase price of new electric cars will be equivalent to that of traditional internal combustion engine-powered autos. Given this outlook, demand for oil, including biodiesel, is likely to come under threat in the future.

Krungsri Research’s view

Over the 3 years from 2021 to 2023, demand for biodiesel will continue to rise. This will be lifted by stronger economic recovery, growth in online retail, and government support for palm growers and processors that will encourage greater consumption of biodiesel in the diesel mix. However, this same desire to support the agricultural sector may lead the government to interfere with palm oil prices and this, together with possible shortages in the supply of CPO, may adversely affect the industry and reduce future profitability.

[1] There are over 70 such community production centers across the country. The majority of these are teaching centers or organizations that promote the production and use of biodiesel by local communities.

[2] The regulations for specifying the biodiesel price reflect the real costs of production by considering the costs of 3 main inputs: crude palm oil (CPO), refined bleached and deodorized palm oil (RBDPO), and palm stearin.

[3] The Alternative Energy Development Plan (2018-2037), or AEDP 2018.

[4] The Department of Energy Business is responsible for setting the proportion of biodiesel in the diesel mix in line with the amount of palm oil available after household consumption has been taken into account.

[5] With effect from March 23, 2020.

[6] Calculated on the basis that 1,000 liters weighs 0.865 tonnes

[7] Includes B7, B10, B20 and other types of premium diesel.

.webp.aspx)